« Features

It’s Not About Having the Last Word

I write art criticism for two reasons: 1. To find out what I think about what I’m looking at; and 2. To make the world safe for me. The first is pretty simple. So is the second, but it’s a little harder to explain.

When I walk into an exhibition or come across something that asks me to take it seriously as a work of art, I rarely know what this means. So I have to spend some time with it: looking, gazing, glancing and all that, but also pondering, putzing around the nooks and crannies of the experience, and noodling through the impressions the thing generates in my body. That includes my brain (lizard and otherwise), as well as my gut, solar plexus, and spine, along with my skin, the hairs on the back of my neck, and my eyes, which sometimes seem to have minds of their own-certainly the capacity to move more swiftly than my intellect, which, in front of the really good stuff, scrambles to keep up with the abundance of data that is being sent to it via rest of myself. The point is that I don’t know what I think of something the split-second I lay eyes on it. And, more, that I am interested-even compelled, as if by forces beyond my control-to try to figure out what I think of it. Curiosity may kill the cat, but without it art criticism wouldn’t exist.

Michael Reafsnyder, Summer Strut, 2016, acrylic on linen, 60” x 72.” Courtesy of the artist and Ameringer/McEnergy/Yohe.

Art’s capacity to generate incomprehension, laced with curiosity, urgent and otherwise, suggests that it stands out from much-but not all-of what passes for contemporary communication. Its attractions and satisfactions can be instantaneous and superficial. But they are not only that. Art that sticks in one’s craw and makes fascinating demands on one’s consciousness requires sustained contemplation and analysis and re-experiencing-a potentially endless process in which parts come together to make wholes, which are themselves parts of other wholes, or fragments of strange, inexplicable worlds that throw more things into question, inviting further adaptations, recalibrations, and developments.

Art’s capacity to get me interested in my interest in it sounds as if it could get pretty meta-, or academic, in a house-of-mirrors, navel-gazing sort of way. But it’s actually pretty selfish, in a social, sort-it-out-in-the-world sort of way. When I’m paying attention to the ways in which I am paying attention to things, I’m not simply standing back, observing and analyzing a situation as dispassionately and objectively as I can, like a meteorologist on the 11:00 o’clock news. I’m in the thick of things, going back and forth between a world of physical objects and abstract ideas, materials and meanings, events and comprehension, trying to come to understand if my private desires line up or collide with public interests, and what what’s in front of me says about how those realities dovetail-and depart from-one another, changing, sometimes subtly and sometimes abruptly, as some kind of understanding is negotiated, between myself and its surroundings. The point is that my self is not a resolved, settled, or polished sort of entity: It’s a messy, ever-changing constellation of experiences and contexts, which includes lots of others, as well as good old-fashioned otherness-discoverable and otherwise. Like art, identity is a question, and criticism facilitates and fosters dialogue between the two.

All of this suggests that making the world safe for me has nothing to do with shoring up certainties, reinforcing stereotypes, following formulas, or building barricades, symbolic and otherwise, between me (with the help of my like-thinking compadres) and everyone who seems to disagree with us. Such militaristic models and territorial formats are at the root of our culture’s tendency to see everything through the lens of sports, where rules and regulations make it easy to tally wins and losses, distinguishing between the victors and those over which their victories are won (the defeats?). The winner/loser, us/them, yes/no, all-or-nothing bluntness of such thinking has spilled into, if not taken over, politics, which has become a spectacle unto itself, and not just during election season, which lasts longer than ever before, nearly rivals the late days of the Roman Senate for its short-sighted self-destructiveness, and makes about as much sense as December baseball and playoff basketball in July. Despite the best efforts of the auction houses, art fairs, and some biennials, art has not yet been swallowed up by such thumbs-up/thumbs-down either/or-ism.

Criticism has something to do with this. Freewheeling discussion, contentious disagreement, and rebellious dissent are integral to it. Art of all shapes and stripes provides occasions of all shapes and stripes for arguments of all shapes and stripes, and criticism’s job is to cultivate conversations, building blunt, ‘I-can’t-believe-you-see-it-that-way’ confrontations into civilized discussions in which differences are at least tolerated, if not respected-especially when they go on within oneself, and not only between people interested, more or less, in art’s capacity to get us to talk about what is important to us, like integrity, justice, and grace, in ways that are funny, elegant, or conflicted, which bring to mind notions of truth and beauty, but without the burdensome solemnity-or ridiculous pretense-of such heavyweight abstractions.

The capacity for conversation, even about stupid subjects, is integral to civilization. Even a few minutes of it reveals a lifetime of experiences. And the greater your perceptual acuity, the more you can see, the more you might know, and the more you have the opportunity to respond to-intelligently, sensitively, and with your eyes wide open-to the consequences of your actions. All of this goes to the heart of what it means to be human, and not merely animal, although the importance of our animal selves is often overlooked by critics whose work too narrowly focuses on logic, rationality, and language. To me, ‘making the world safe for me’ means making room, in the world, for the unpredictable back-and-forth of thoughtful conversation, between others and within oneself-between one’s various selves. None of this would exist without the capacity to see things from various perspectives. Doubt, self- and otherwise, is a constant presence. But so are conviction, clarity, and commitment. And it is the back-and-forth dance between knowing and not, between clarity and confusion, that drives criticism outside of itself, more closely toward the art it seeks to comprehend and more deeply into the world it wants to make sense of. Whatever sort of self starts out on that unmapped path is transformed along the way. A sense of expansiveness is integral to this process. Your world gets bigger, as does your awareness of your place in it, which includes real constraints, but real possibilities too.

So what I try to do as a critic is to make more room in the world for works that make more room for this sort of socialized-and socializing-self-reflection, using my voice and whatever venues I have at my disposal to bring the attention of as many others as possible to art that seems, to me, to be transformative. The flip side of my attempt to shine a little light on works that change the way I see the world and inhabit it-and invite others to do something similar-involves making less room in the world for works that are not up to the challenge of such intimate originality or, if the O-word rubs you the wrong way, rejuvenating recreation. That lumpy phrase eliminates divinity and emphasizes, instead, playfulness, in a way that shifts America’s unholy love of labor (or fetishization of work) toward an acknowledgement of leisure’s place in the development of what it means to be a civilized human, while suggesting that every last one of us might be divine, if we only knew how to relax, let go, open up. In any case, time is short and one way I try to make the world safe for me is by trying to get people to pay less attention to art that does little more than tell us what we already know, by shoring up stereotypes, reciting tired stories, patting itself on the back, being pointlessly esoteric, and by fitting, as professionally as possible, into business as usual, which is sometimes referred to as ‘the dominant discourse,’ ‘the institutional infrastructure,’ or, my favorite logical impossibility ‘contemporary art history.’ In the old days, Claes Oldenburg dismissed this sort of stuff as “Art that sits on its ass in a museum.” Today, art doesn’t even have to trouble itself with getting into a museum: It sits on its ass wherever it pleases. That’s bare-naked privilege. Even though it’s the rule of the brave new art world, there are plenty of exceptions. As a critic, that’s what I’m after. Time may be short, but attention spans are malleable. Making room for the art I love goes hand-in-glove with getting people to spend more time with it, both face-to-face and after-the-fact, in the mind’s-eye, where it resonates with some of the other things that have made an impression on us.

Ron Nagle, Topbana, 2013, mixed media, 4 ½” x 5” x 3.” Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery.

What I do as a critic who writes mostly for a daily newspaper is all about specifics: how, for example, a particular group of pictures at this time and in this place uses color and texture and whatever else might be germane to its purposes to trigger a set of experiences that convey something significant about human purposefulness and futility or, perhaps, about pleasure and regret, ambitions and their diminishment, or anything else, for that matter, that is worth coming to terms with, right here and right now, for whosoever happens to lay eyes on it. I prefer the fleshy pedestrianism of such down-to-earth encounters to the high-minded machinations of academic discourse and, especially, to the tempest-in-a-teacup dealings of over-professionalized specialists, who seem to want, nothing more, than to show themselves to be bona fide members of an esoteric enclave whose interests are too nuanced for most folks to understand, much less to want to share.

I like newspapers because they are not meant for insiders. The writing inside them holds onto the proposition that there is such a thing as a general public, which is worth fighting for, especially in an age of rapidly multiplying niche cultures and what they strive to stand against, or at least out from: the sanitized blandness and rampant superficiality of corporate culture, whose capacity to shape consciousness is as frightening as globalism is here to stay, at least for the foreseeable future. Criticism is not rocket science. Nor is its job to appeal to every Tom, Dick, and Harry. I am interested in it because it holds out the possibility that the sophistication, precision, and mind-blowing effectiveness of the former are not the provenance of experts, but available to just about anyone, and that this come-one, come-all accessibility does not require that its subject’s rough edges be smoothed over, its loose ends eliminated, its uncomfortableness made palatable, and its complexities dumbed-down so that it can be consumed as swiftly-and profitably-as possible. The point and purpose of criticism is not to propagate some market-driven illusion of the greatest good for the greatest number. It is to make the goods count for individuals, whose singularity is not diminished by being shared with others. The rub is in determining what works for whom. And criticism, when it works, facilitates the conversation by leaving readers free to make up their own minds, after the critic has made his case, as persuasively as possible. It’s a no-holds-barred endeavor, the only caveat being that every reader has the power to determine what counts for him. Turning the page is as effective a form of criticism as is any other.

This check-it-out-and-decide-for-yourself informality is at the heart of criticism that prefers real consequences to good intentions. Everyone means well. Too often, doing well is something else altogether. Getting from the former to the latter is risky business. It involves all sorts of unpredictability, not least of which are the whims and proclivities of one’s audience. Jury trials are exciting-and frightening-for that very same reason. Critics make judgments; but every reader is his or her own jury. That’s where the real authority, and lasting consequences, reside, rippling out toward and through others, who form a fluid community of art lovers.

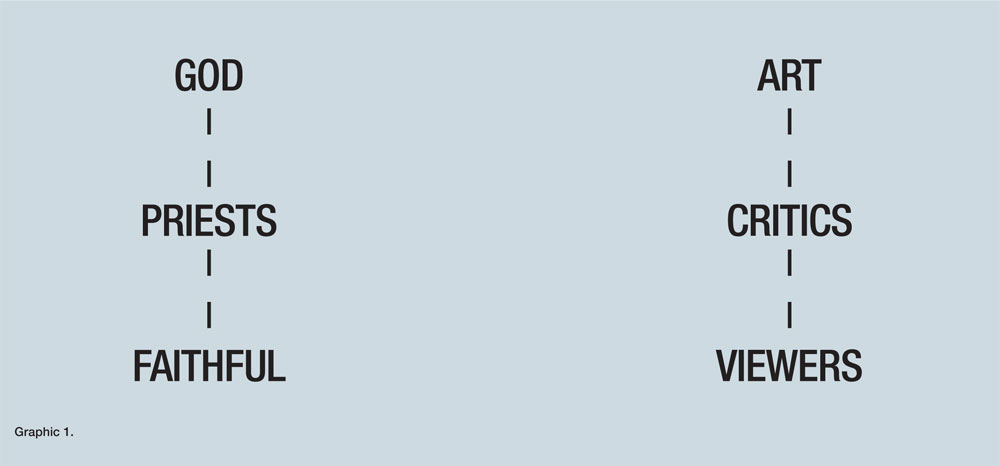

What I do as a critic has nothing to do with upholding standards, even though that’s what lots of people (who should know better) presume. Critics are not gatekeepers, nightclub bouncers, or security guards hired to restrict access to exclusive establishments. Such conservative thinking takes us back centuries-to the time before Luther. Back then, the faithful could not get to God without the intercession of the clergy. Today, many people act as if critics function as pre-Luther priests, lording their authority over viewers by insisting that a viewer’s access to art depends upon the intercession of the critic. This is how those two worlds look:

God and art-too difficult, complex, and otherworldly for common folk to understand on their own-need priests and critics if they are to have audiences that understand even some of their infinitely mysterious ways. At the same time, the plebeians at the bottom of this top-down diagram-the faithful and the art viewers-need priests and critics if they want to comprehend anything more than the basics of what is intrinsically over their hands. This setup conveniently puts priests and critics in the most important position on Earth, at least in terms of facilitating the interaction between what’s at the top of the heap (God and art) and who’s on the bottom (the faithful and the viewers). It’s little more than a naked power grab by people too shortsighted to see where the real power resides and transpires, or, if they do, unwilling to go there because it’s too risky, open-ended, and difficult to control.

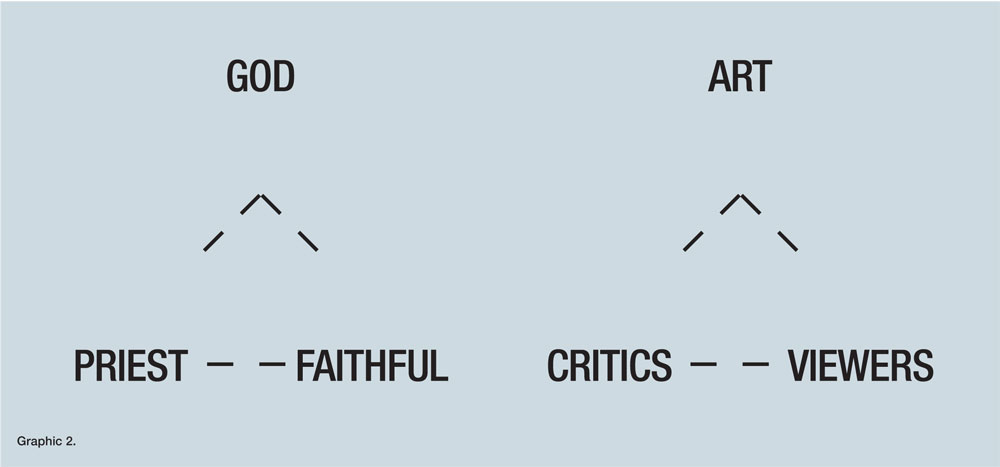

In contrast, the criticism that moves me, and which I strive to emulate, works like this:

God and art are still on top. But in the triangular diagram on the left, the faithful have moved up; they are on the same level as the clergy. In the secular version, or the diagram on the right, something similar has taken place. Critics and viewers are on the same level, each just one step away from what they both seek to understand, to be close to, to commune with, and to interact with as directly as possible: art. So, rather than having the situation set up so that critics control access to art, everyone is in the same position in relation to what we are seeking. The mediation of the middleman has been eliminated.

As a critic, I may spend more than time interacting with art than most viewers do, but my relationship to it is no more special or privileged or sanctified than theirs is. What I do as a critic is relate myself to art in as unmediated a manner as possible-as intimately and intensely as I can. Then, as clearly as possible, I convey the nature of that relationship-the ins and outs of the experience-to viewers, trying, to the best of my abilities, to persuade them that it is not only worthwhile, but something they might want to experience for themselves. I invite viewers to relate themselves to the art, to see, up-close and in person, how it goes with them, and then, and only then, to compare and contrast their firsthand experience with the way I described and analyzed mine. Ultimately, it’s up to each and every viewer to decide if what I said makes sense, whether it gets them to see their world differently or was off the mark and instead got in the way of their understanding of what the art meant to do and actually did. If all of that doesn’t generate debate, discussion and argument, I don’t know what does. In any case, critics and viewers are on a level playing field, doing, basically, the same thing. No critic has the last word. Hopefully, what we say gets a conversation or two started, and all kinds of words come after ours, some of them civilizing.

* This essay is included in the forthcoming anthology, ART of Critique/ Reimagining Professional Art Criticism and the Art School Critique, edited and compiled by Stephen Knudsen.

David Pagel is an art critic who writes regularly for the Los Angeles Times. He is a professor of art theory and history at Claremont Graduate University and an adjunct curator at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, N.Y., where he organized “Underground Pop” and “Damaged Romanticism.” An avid cyclist, Pagel is a five-time winner of the California Triple Crown.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.