« Features

Lari Pittman: Rotten America

By David Pagel

Overripe is one step away from rotten. When mature fruits and fresh vegetables pass their primes, they begin to stink, their once firm flesh going mushy, their skins withering, and their sweet juices pooling in puddles that become breeding grounds for insects, both filthy and annoying, before drying up and disappearing, except for the stains they leave on the bottom of the bowl. The same goes for nations when they lose their capacity to maintain some kind of balance between production and consumption, not least of which is some minimum standard of living for the majority of their populations whose well-being is essential to the vitality of the whole.

This is the territory traversed by “Lari Pittman: From A Late Western Impaerium,” the L.A. painter’s gloriously melancholic exhibition that takes one giant step back from the myopia that defines so much of modern life to give Americans (from both continents) a big-picture view of our place in history. Filled with violence, sickness, and corruption, as well as cruelty, loss, and betrayal, it’s not a pretty picture. But Pittman handles the bad news with aplomb, neither sugar-coating the grim facts of reality by pretending that things will get better if we all just work a little harder, or pointing fingers, like politicians and pundits, at others-across the aisle or political spectrum-whose un-American cluelessness is supposedly responsible for the problems, which are grave. If the 62-year-old artist were a doctor, and his astringent exhibition a prognosis, it would be terminal.

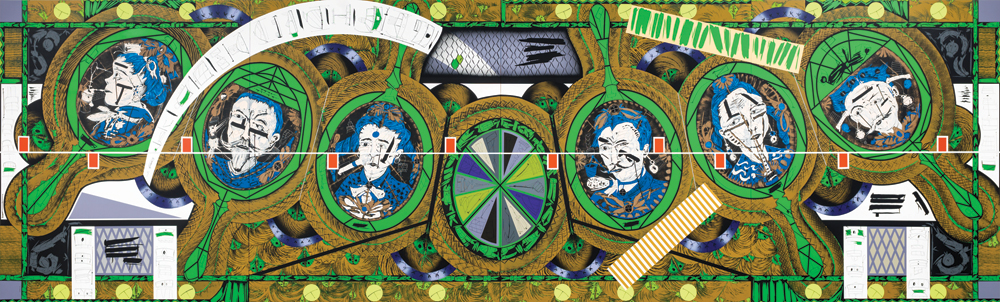

Lari Pittman, Flying Carpet with Petri Dishes for a Disturbed Nation, 2013, Cel-vinyl, spray enamel on canvas over wood panel, 108” x 360¼.”

The causes of rot are legion, but their consequences are uniform: weariness, regret, and despair, which lead to more misery, more suffering, and increasingly frequent, and high-keyed cycles of denial, rage, and acceptance-or deeper and deeper depression, both emotional and economic. The economy of human emotions, and their relationship to the psychological underbelly of the global economy, is Pittman’s great subject. He has pursued it for more than 30 years, often with furious eloquence, biting wit, and scathing insight, in paintings that have matched the impossible exuberance of bubble economies, kept pace with the steadiness of slow-growth investments, and captured the disquiet of stasis (a la Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere”), all the while giving razor-sharp form to the pleasures and pitfalls of business as usual, when crashes and recoveries exacerbate the vertiginous ups-and-downs of mood swings.

In the past, the optimistic principles on which the United States of America was founded played a major part in the hot-blooded opera of Pittman’s high-octane paintings. Today, the various manners in which these democratic principles have soured, curdled, and clotted as they have been hijacked by avaricious 1 percenters take center stage in his one-man overture, coming to fruition in a multi-gallery extravaganza that invites visitors to view the present from a point far off (or perhaps not so far off) in the future, looking back on today as if it were a dimly recalled memory, its seemingly intense darkness not such a big deal now that it has taken its place in the background of a more expansive vision of human history. In Pittman’s polyvalent, kaleidoscopic view, time does not heal all things; it just cuts them down to size. Whether that’s cruel or justified depends on your perspective, not to mention how much skin you’ve got in the game.

Pittman’s no-holds-barred exhibition opens with a suite of 12 handsomely framed works on paper. In the foyer hangs Twelve Fayum From a Late Western Impaerium (After Hermenegildo Bustos), a grid of imaginary, medallion-style portraits, whose muted, sepia-toned palette of dirty gold, oxidized silver, and luminous blue makes them look radioactive, less dead-and-gone and still very much a part of the present, which hasn’t quite turned out as planned, not by a long shot. Referring to Imperial Rome, Coptic mummy masks (Fayum), and 19th century portraits of a newly emergent Mexican middle class, Pittman’s sitters appear to be anything but comfortable with their social positions: not quite shell-shocked, but painfully aware that they are playing dress up and that the charade is rickety and doomed. Far from conveying confidence, evoking authority or embodying a sense of age-old grandeur, they have the presence of a cloistered aristocracy going through the motions of its last days, as if they were a long-lost branch of the Habsburg Empire, so far off the beaten path that they haven’t got the memo that nationalism, not to mention democracy, have swept the old ways away.

The desperate, message-in-a-bottle feel to Pittman’s suite of ornate paintings on paper drifts throughout the exhibition, suffusing it with the sense that the show as a whole is less of a memento mori meant to remind contemporary visitors of our mortality than a handcrafted communiqué intended for the eyes and minds of future generations. Pittman, ever the imaginative showman, does not address living viewers directly so much as he gets us to imagine that we inhabit the future and, having stepped into his time-capsule of an exhibition, are given the privilege of looking back at the early 21st century as if it were ancient history. It’s a strange sensation, more common to literature, even poetry, than painting. But “Lari Pittman: From A Late Western Impaerium” pulls it off gracefully, jerking visitors out of the self-satisfied narcissism of so much so-called social media by making us feel as if we are examining a treasure trove of archaeological evidence from a time and a place well past its prime: overripe, in polite terms; rotten, in less decorous language; our own, either way you parse it.

Lari Pittman, New National Anthem and Lamentation Duet with Birds (After Puccini), 2013, Cel-vinyl and spray enamel on gessoed paper, 8 drawings, each 30½” x 20¼.”

A pair of doors flanks the portraits and leads visitors into a gallery that functions like an old-fashioned antechamber. Here, two big paintings and two suites of framed drawings flesh out the grim atmosphere of Pittman’s exhibition and hint at what is to come in the main gallery. The paintings, Needlepoint Sampler with Patches Depicting Daily Life of a Late Western Impaerium (#1) and (#2), hang opposite each other, like a diptych that doesn’t get along with itself, or a pair of mirrors that don’t work properly, their distorted reflections making a mess of both symmetry and sense. The imagery in the 9-by-7½-foot paintings is similar: the stylized silhouette of a needlepoint hoop, painted with hard-edge precision, floats like a cartoon bomb or oversize molecule on a dark ground populated with wickedly stylized figures that resemble the misbegotten offspring of comic strips, kachinas, marionettes, taxidermy birds, voodoo dolls, kids’ toys, and ventriloquist dummies.

To stand between Pittman’s paintings is to feel like a vampire, invisible between two mirrors. Although the canvases hang face-to-face, they fail to create the illusion of infinite regression and instead leave you with a sense of claustrophobia-crowded out, or overrun, by the idea that the damage has been done and there’s nothing left but to get used to it. The two sets of drawings on each of the remaining walls intensify the sensation of time and space collapsing. In eight parts, New National Anthem and Lamentation Duet with Birds (After Puccini), stages an aria from Puccini’s Tosca as puppet-theater, its heart-wrenching sorrows all the more poignant for the silliness of Pittman’s protagonists, whose crude, wood-cut features, bright, clashing palette, and rosy-cheeked glow combine to suggest not healthy vigor but feverish frenzy. For its part, Twelve Reliquaries of Souls Trapped in Amber (From a Late Western Impaerium) is a cemetery-style memorial to lost possibilities, the golem-like forms of Pittman’s unborn protagonists preserved for eternity in art’s stately silence.

Nothing prepares you for the scale and drama of the main attraction: a trio of 30-foot-long paintings in the central gallery, which Pittman has transformed into a room that recalls the great halls of medieval castles decked out for festivities. Like gigantic tapestries, or a disjointed triptych, his operatic ensemble of mural-size canvases displays stories interwoven with odd emblems and abstract patterns, all of which work in concert to tell tales of epic misadventure, noble and otherwise. Clockwise, from the entrance, hang Flying Carpet with Magic Mirrors for a Distorted Nation, Flying Carpet with Petri Dishes for a Disturbed Nation, and Flying Carpet with a Waning Moon Over a Violent Nation. In the first, six handheld mirrors, which my grandmother called looking glasses, swing like a stop-action pendulum across an abstract pattern that never lets your eyes rest. Its fractured forms, asymmetrical shapes, and syncopated geometry engineer a rollercoaster ride for eyeballs-a topsy-turvy trip that would be even more dizzying, or nauseating, if the painting’s palette of lizard green, honey gold, and blazing blue were not so strangely soothing. The faces in the mirrors belong to people beefier and meaner than the emaciated aristocrats in the 12 portraits in the entryway, whose nuclear blue hairdos make sickliness look normal.

Lari Pittman, Flying Carpet with Magic Mirrors for a Distorted Nation, 2013, Cel-vinyl, spray enamel on canvas over wood panel, 108” x 360-1/8.”

In the second painting, a pair of supersized Petri dishes, seen from above as if through a microscope, form two perfect circles. Echoing the shape of binocular lenses, or a severed infinity symbol, the abutted circles anchor the most symmetrical of Pittman’s compositions. Bugs, ducks, and handguns pop up all over the place, as do pink triangles, black bullet holes, and the solar panels from satellites that have fallen apart but have not yet fallen to Earth, along with a beautifully painted array of evocative, Rorschach-style blobs. The rationality of science and the orderliness of symmetry are no match for the chaos that simmers and stews across every square inch of the fiery red-orange surface of this monstrosity of a masterpiece.

The third painting pulls back spatially, but doesn’t yield an inch, its noirish atmosphere as unrelenting as the real thing. Against a midnight blue backdrop and three Old West nooses, five circular, red-ringed windows depict various phases of the moon as it wanes its way toward invisibility. Pittman displays the celestial orb through the telescopic sight of a sniper’s rifle, suggesting that even stone-cold killers can be moved by the beauty of nature. Beauty’s impotence in the face of violence takes chilling shape in this darkly realistic picture.

And as if that weren’t enough, Pittman has installed a 12-piece suite of drawings on the fourth wall. In Set Arrangements of Ballet Mecanique for a Fossilized Nation (After Leger), the hardworking overachiever brings the attentiveness of a miniaturist and the precision of a watchmaker to the dreamy world of shadow puppetry. Curtains part, bells toll, skulls grin, and imaginary beasts spring to life, if not on the tiny stages Pittman depicts, certainly in your imagination. That is the territory where his art does its most potent work. The vertiginous, head-spinning shift in scale, from the walloping trio of murals to the intimacy of these screen-size pieces, drives the point home.

To see the rest of the exhibition, you must retrace your steps back to the foyer and go left, where two side galleries display five more suites of drawings. They bring the total number of works on paper and canvas to 92, all of which Pittman has painted by hand and without assistants over the last eight months. The number alone is impressive and speaks to the work ethic at the root of his art. Once the province of the Protestants who played a large part in the founding of the United States, this good old American work ethic is transformed, in Pittman’s hands, into an activity that keeps depression at bay because it is based in the conviction that all is not yet lost and that it still makes sense to put your best foot forward by telling the truth about what you see, whether or not anyone else may understand.

Lari Pittman, Twelve Fayum From a Late Western Impaerium (After Hermenegildo Bustos), 2013, Cel-vinyl and spray enamel on gessoed paper, 12 drawings, each 20” x 16.”

The two sets of drawings in the first side gallery are abstract diagrams that picture nothing in particular yet give crisp physical form to the dread and anxiety and gnawing unease many folks feel when the future looks a lot dimmer than expected, its horizons of possibility shrunken, stripped bare, depleted. The eight claustrophobic compositions that make up Aerial Night Views of Secured Districts of a Late Western Impaerium recall security monitors at a surveillance center, evoking images that survey not the visible landscape but the watchful eye of big brother, its technologically enhanced capacities similar to the faceted eyes of insects, whose Kafkaesque horrors are made elegant-and all the more horrifying-by Pittman’s chilly images. Likewise, Twelve Pavilions Designed for Viewing First-World Atrocities turns things around in its point-blank depiction of sensible buildings constructed for unconscionable purposes. Its preposterous proposition captures the insanity that passes as business as usual, bringing into sharp focus the inability, or unwillingness, to distinguish rationality from its opposite, not to mention right from wrong, truth from lies, entertainment from exploitation. In the surreal world we inhabit, the original Surrealists would be at their wit’s ends to make sense of things. This is where Pittman’s images begin, playing absurdity against insanity for purposes that are perfectly reasonable, even old-fashioned.

In the last gallery, Eight Encampments as Civic Centers (From a Late Western Impaerium) elaborates upon the David and Goliath relationship between the haves and the have-nots, making a little space for the civility and discourse that are integral to democracy in a society seemingly hell-bent on quashing such disruptive inconveniences. In the 12-part Staging Variations of an Opera for an Entropic Nation, Pittman’s ghostly golems return.

The intoxicating mélange of phantasmagorical apparitions and penetrating realism in “Lari Pittman: From A Late Western Impaerium” is both majestic and matter-of-fact. It gives visitors a kick that sometimes seems to be the visual equivalent of hot flashes-unbidden, unwelcome, disorienting-and at others seems be absolutely lucid, so clear-eyed and grounded that it’s impossible to see it as anything other than objective.

Part of that has to do with the fact that Pittman’s paintings are super-realistic depictions of a world in which delusional behavior has become normative. The myths our most powerful citizens live by do not elevate or inspire: they diminish, belittle, and stultify-strangling what is vital in society by turning everyday life into a mean-spirited struggle for survival, at best a holding operation that aims to cut loses, hedge bets, and stave off disaster. When that happens, culture grows overripe and rots. Up close and in person, everyday life turns into a low-budget, do-it-yourself version of a sequel: the same old stuff gets trotted out, once again, with all the moves and manners of the first time, but none of the wonder or sense of discovery that once made it memorable. Going through the motions is all that is left because what’s on the horizon is worse: the end of everything not only cherished but hoped for.

That’s where Pittman, the indefatigable painter, enters the picture: Cramming his desperate message into a gallery-size bottle, he shows visitors what an individual can do with two hands and a paintbrush when he cuts to the chase and leaves no room for self-pity.

David Pagel is an art critic who writes regularly for the Los Angeles Times. He is a professor of art theory and history at Claremont Graduate University and an adjunct curator at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, N.Y., where he organized “Underground Pop” and “Damaged Romanticism.” An avid cyclist, Pagel is a five-time winner of the California Triple Crown.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.