« Features

Occupy Space/Time: Time-Folding in Contemporary Art

“Because no work of art exists outside the linked sequences that connect every man-made object since the remotest antiquity, every thing has a unique position in that system. This position is marked by coordinates of place, age and sequence. The age of an object has not only the customary absolute value in years elapsed since it was made: age also has a systematic value in terms of the position of a thing in the pertinent sequence.”

-George Kubler, The Shape of Time

By Jason Hoelscher

The ambiguity and unfinalizable aspects of art-arguably the very qualities that make art “art” as opposed to something else-seem to create an urge for classification and categorization. Entire eras, diverse in temperament and geography, are subsumed under the label of Renaissance, or the work of artists as disparate as Barnett Newman and Willem de Kooning are grouped under the label of Abstract Expressionism. While such information streamlining shears off much nuance-which Renaissance? Italy in the late 14th century or England in the late 16th?-it is undoubtedly a valuable shorthand if we are to be at all able to discuss art without endless qualifiers and details.

What, then, does it mean to discuss “contemporary” art? Unlike the periodization of eras such as “fin de siècle modernism,” “contemporary art” is slippery in terms not only of definition but also regarding what it even refers to in the first place. The word contemporary, like the word “I,” is what Russian linguist Roman Jakobson would call a shifter, a signifier detached from a stable referent, applied contingently and changing in meaning according to who uses it and when. In practice it comes to mean less with each usage: contemporary now refers to a range of artworks, whether those created at any time since 1960-as at auction houses like Christie’s or Sotheby’s-or those created last month.

The condition and meaning of the contemporary takes on a still different set of complications when considered in light of three exhibitions that took place in Europe during the summer and autumn of 2013, namely “When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013,” at the Fondazione Prada in Venice; “Les Papesses,” at the Palais des Papes in Avignon; and “Paris Tour 13,” which took place in a ten-story derelict housing project building in Paris. All three of these exhibitions were quite extensive, occupying entire buildings ranging from palaces to projects, and shared highly problematized relationships to space, time and presence. These complex temporal entanglements operated in three distinct, if overlapping ways: time-as-collage, artistic re-temporalization, and the exhibition as chronotope.

Louise Bourgeois (Spider, 1995, steel). Installation view from “Les Papesses” at Collection Lambert, Avignon, (June 9 – November 11, 2013). Photo: Kory Kingsley.

“When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013,” curated by Germano Celant with input from Thomas Demand and Rem Koolhaus, was a reiteration of Harald Szeemann’s seminal 1969 exhibition, “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form.” Szeemann’s exhibition featured a range of conceptual, post-minimal and anti-form artists such as Joseph Kosuth, Eva Hesse, Joseph Beuys, Hanne Darboven, Richard Tuttle and others, and is often credited with bringing such work to international prominence. Exhibited at the Bern Kunsthalle, a large warehouse space, much of the work was made of evanescent and impermanent materials like sound, wire, felt, and lard. The recent iteration of the show in Venice not only sought out and re-staged these ephemeral artworks but re-created the warehouse space itself inside the cavernous rooms of the Ca’ Corner della Regina, an 18th century palazzo along the Grand Canal in Venice.

The Venice exhibition thus operated as something of a remake, a fairly common event in popular culture-think of movie remakes, dance remixes or cover songs-but one not so common in fine art. To use the example of cover songs, new versions of old tunes tend either (a) to remain note-for-note true to the original, such as the current vogue for classic rock tribute bands, or (b) are used as an interpretational jumping-off point to create a quite different song. “When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013,” intriguingly enough, managed to pull off the latter interpretational feat by strictly adhering to the note-for-note methodology of the first. In other words, by meticulously researching and re-creating such details as the precise placement of the original works relative to one another, the re-creation’s fidelity to the original was an important component of the exhibition: if a work in the 1969 iteration happened to be 44 inches away from another work, and arranged at a 70-degree angle from the wall, that relationship was carefully reconstructed in Venice in 2013.[1]

Installation view from “When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013” at Fondazione Prada, Venice (June 1 – November 3, 2013). Photo: Tullio M. Puglia/Getty Images for Prada. Courtesy of Fondazione Prada.

So far this is fairly analogous to the note-for-note re-creation of an older song. Where Venice 2013 differed, however, was in the careful reconstruction of the original in such a thoroughly different context, from the industrial space of a warehouse to the aristocratic environment of a palace. Beyond the precise replacement of the works in their original configurations within a vastly different type of space-an interesting conceptual tactic to begin with-the space and feel of the warehouse itself was re-created 1:1 within the palazzo, up to and including the walls and floors. Overlaying blueprints and diagrams of the two distinct spaces, the curatorial team had plain white walls inserted into the palazzo, a radical superposition of not just architecture and functionality but also of class implications, juxtaposing sheetrock with fresco. Mitered and cut when necessary to flow around such distinctly non-industrial accoutrements as 18th century columns and balustrades, the juxtaposition of wall types was a detail considered crucial enough to the show’s thesis that it came to represent the exhibition in advertisements and on the cover of the catalog. Such strict adherence to history was complicated still further when, to take but one of many examples, a reactivated anti-form scatter piece rested directly below a centuries-old fresco, thereby creating a contextual, experiential and temporal collage of otherwise discordant elements.

To return to the cover song analogy, the precise “note-for-note” reconstruction of the artworks and their placement, when juxtaposed with the strange surroundings, created a far more dynamic tension than would have been the case had the artworks simply been exhibited in the palazzo without the strict fidelity to the original. For that matter, the attempt to re-situate the Bern space in Venice, building warehouse walls jigsaw-cut to fit 18th century architecture, served to create strange asymmetries in time, space and context. More than just a re-creation or re-situation, the complex folding, mashing-up and interlacing of times-an exhibition from the relatively recent past rebuilt in the present into a much older setting-combined with the radical shift in context to present the exhibition as readymade: a double-occupancy of space and time that transformed one artifact into another-not by modifying the thing itself but by drastically changing its situation.

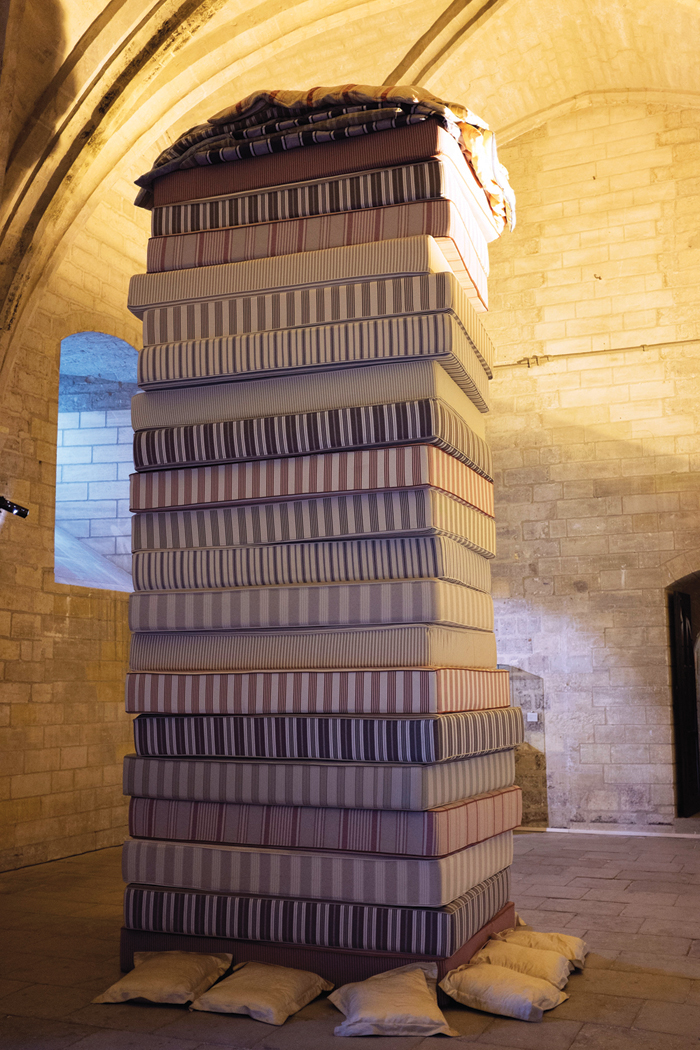

Jana Sterbak (The Real Princess, 2013, mattresses). Installation view from “Les Papesses” at Collection Lambert, Avignon, (June 9 – November 11, 2013). Photo: Kory Kingsley.

“When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013,” then, is in many ways about the complications and asymmetries of reenactment, dislocation and re-territorialization. Re-territorialization, a term used by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari to describe the re-placing of a system-such as a species or a language-into a new situation or environment after being uprooted from its previous territory of influence,[2] can be applied also to Les Papesses, a concurrent exhibition that ran in Avignon from June through November, curated by Éric Mézil, director of the Yvon Lambert Collection.

Exhibited in the Palais des Papes, a Renaissance castle that housed the popes during the Catholic schisms in the 13th and 14th centuries, “Les Papesses” featured the work of Camille Claudel, Louise Bourgeois, Kiki Smith, Jana Sterbak and Berlinde De Bruyckere. Made up primarily of monumental sculpture-the smaller work was exhibited across town at the Lambert Collection building-the palace was filled with works such as the massive Spider sculptures of Bourgeois and Sterbak’s The Real Princess, a stack of mattresses that reached nearly to the ceiling of a grand hall. While the exhibition was curated around the medieval legend of a 9th century female pope known as Pope Joan, what is of interest here is the juxtaposition of space and time as an incongruous collision of art and place.

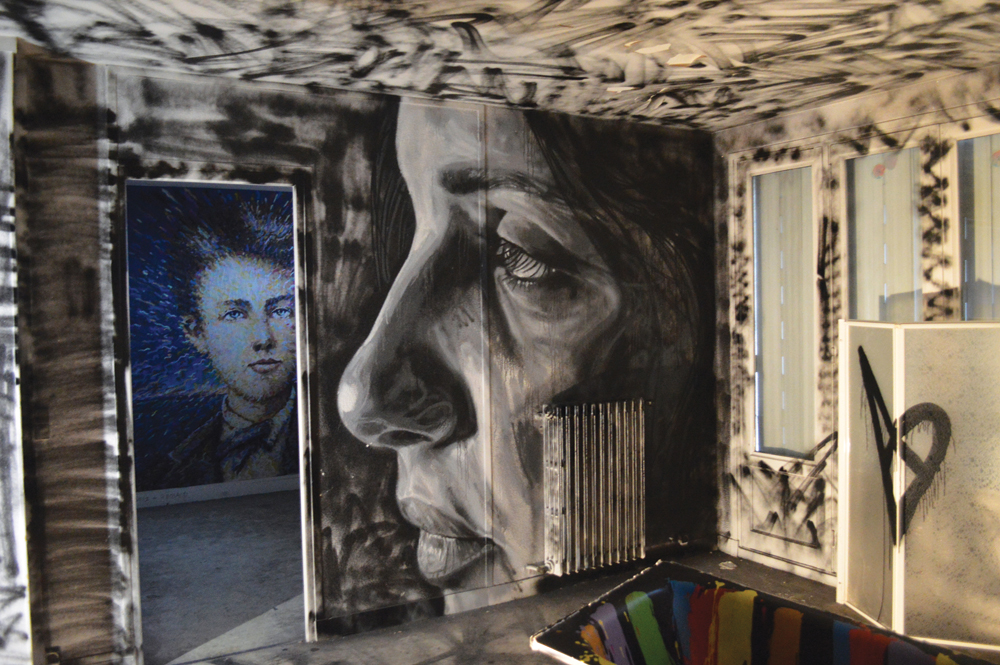

David Walker (foreground), Jimmy C. (background). Interior view of “Paris Tour 13,” an abandoned building called Habitat de la Sablière (October 1-31, 2013). Photo: Jessica Hernández.

At the most basic level, seeing the work of an artist like Louise Bourgeois-humorously described in the exhibition catalog as “the anti-Papess”-within a papal palace in a medieval walled city is itself something of a shock: what the popes and clergy who lived and worked there over centuries might have thought is an interesting mental exercise. If “When Attitudes Become Form” drew much of its power from its exhibition of itself as itself in quite different spatiotemporal circumstances, “Les Papesses” pulls off a similar feat by taking one situation-modern and contemporary works by women-and superposing it into the extremely unlikely context of a 700-year-old papal enclave, inhabited for centuries almost exclusively by men. These re-territorializations, of gender, aesthetic priorities and power relations, also serve as what we might call re-temporalization, the transfer, recalibration and re-situation of time relationships: both artwork and exhibition space take on quite different implications when set against, aside, and with one another. Whereas the Venice exhibition managed to create a differential tension between like to like, “Les Papesses” created a compelling friction between very different spatial and social systems.

El Seed. Exterior view of “Paris Tour 13,” an abandoned building called Habitat de la Sablière (October 1-31, 2013). Photo: Laila Kouri.

A different approach to temporal complication took place with the exhibition “Paris Tour 13,” a temporary installation that took place in-and in fact took over-a derelict ten-story building in Paris’s 13th arrondissement during the month of October. Organized by Mehdi Ben Cheikh of Galerie Itinerrance, “Tour 13″ featured the work of 80 street artists from around the world who were invited to paint the building-inside and out-however they wished. As elaborately overloaded with visual incident as any palace or chapel, practically every surface of the building’s 36 apartments, from walls to ceiling and from fixtures to exterior façade, was covered with paint or wheat-pasted paper.

While “Tour 13″ was visually impressive, even overwhelming at times, adding to the force of the exhibition was the fact that it had a very firm and definitive closing date: at the end of the month the building was scheduled to be demolished. Complicating a typical exhibition schedule-once over the artworks are taken down and removed-the closing date of “Tour 13″ marked the irrevocable end of both artwork and exhibition space. An example of the exhibition of art as the exhibition itself, via a total fusion of artwork with surface of display in three dimensions, inside and out, “Tour 13″ offered a twist to the relationship of art to site: if the site-specific nature of “When Attitudes Become Form” relied on the ephemeral quality of the art transposed and re-created in a different site in space and time, and the site-responsiveness of “Les Papesses” operated by way of forced sociocultural and spatiotemporal incongruity, the site-responsiveness of “Tour 13″ relied on the aggressive nature of the exhibition’s end, a definitive deconstruction in a very literal sense: present for a very specific, pre-defined period, after the deadline both art and site would be gone for good.

This highlights the importance of presence and presentness in these three exhibitions: in Venice, the presence of a past exhibition as itself, situated in a thoroughly different context in the present;[3] in Avignon, the rather transgressive presence of a new thing in an old context now known largely for the presence of popes now long absent, returned to the Vatican; and in Paris the momentary presence of art and site in a highly particularized, temporally constrained setting. Even the term “presence” suggests the notion of “the present,” a contingent moment in time that, like the word contemporary, has a shifting meaning that defines nothing more or less than a subjective interface between past and future.

Interior view of “Paris Tour 13,” an abandoned building called Habitat de la Sablière (October 1-31, 2013). Photo: Jessica Hernández.

This fluid, shifting quality proposes a way to consider the “Tour 13″ exhibition overall, as an example of a specific type of time/space relationship known as a chronotope. A term coined in the 1920s by literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, a chronotope defines not only a specifically charged intersection point of space and time but also the way the context and language of an event is understood and represented by a culture. Described by Bakhtin as an “intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships [in which] spatial and temporal indicators are fused into one carefully thought-out, concrete whole,”[4] the term chronotope describes quite well the compelling nature of “Tour 13″: the spectacle of the work itself, combined with the knowledge that it would soon be gone, clarified and defined its position in time in a highly charged and gripping manner.

That such different, high-profile exhibitions as these three were mounted concurrently is interesting in implication. Though very dissimilar in feel and look-from anti-form scatter pieces to elaborate street art, from the clash of contexts across centuries to an exhibition closing date enforced by a wrecking ball and demolition crew-the exhibitions’ charged relationships to duration and instantaneity suggest that our own cultural moment is complexly related to issues of presence, absence and presentness as well. In our everything all the time instant-access culture, in which the topology of our planet has been mapped and photographed down to the square inch, perhaps the next stage of the contemporary will be a series of paradoxical, ever-intensified explorations, remixes, reiterations and reconstitutions of an interlaced past and present.

NOTES

1. This marks an interesting progression in the relationship between art and record, from art > documentation to art > documentation > art: If much of what we know about late 1960s art comes to us only from documentary photographs and video, Venice 2013 carried the sequence a step further, using the documentation to reconstruct or replicate the arrangements of works that had, in many cases, been created with impermanence and dematerialization in mind. Further complicating this agenda is that fact that many of the works had long since been taken apart or thought lost.

2. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (University of Minnesota Press, 1987). See in particular chapters 1, 4 and 5.

3. Not to mention the instantiation of absence, by demarcating lost or destroyed artworks with dotted lines to highlight where they would have been placed within the context of the exhibition.

4. Mikhail Bakhtin, “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel,” in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, trans. Caryl Emerson & Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 84.

Jason Hoelscher is a painter, writer and educator. He is a professor at Savannah College of Art and Design and has exhibited his work in New York, Paris, Berlin, Hong Kong and Stockholm. His writings have been published in ARTPULSE, Artcore Journal and various anthologies and conferences. Hoelscher received his MFA in painting from the Pratt Institute and is working on a PhD in aesthetics and art theory from the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.