« Features

Pattern and Deregulation: Beauty and Non-Order in Contemporary Painting

By Jason Hoelscher

“All true feeling is in reality untranslatable…That is why an image, an allegory, a figure that masks what it would reveal has more significance for the spirit than the lucidities of speech and its analytics. This is why true beauty never strikes us directly. The setting sun is beautiful because of all it makes us lose.”

-Antonin Artaud

OBLIQUE BEAUTY

The condition of beauty in contemporary painting is complex, heir to a century of avant-garde exploration and deconstruction. Where avant-garde modernism focused on experimentation over sensuous intake, postmodernism focused more on semiotics and subtext than on surface, with neither approach being particularly focused on beauty. Similarly, theorists as remote in time and temperament as Wilhelm Worringer and Joseph Kosuth sought to sever the ties between art and beauty altogether, declaring the latter to be an extraneous accoutrement.1 In Thierry de Duve’s formulation, the question of 20th-century art shifted early on, from “What is beautiful?” to “What is art?”2

A correlation can be made between beauty and sincerity, a similarly contested notion in recent decades. Writing in 1993, David Foster Wallace noted that American literature and pop culture had replaced sincerity with a distant, emotional flatness, a “pervasive cultural irony” that is “a variation on a sort of existential poker face,” in which staking out a position and saying what one meant was considered banal (Wallace 67). Exploring the corrosive effects of such a stance, Wallace predicted the rise of a new avant-garde, of “anti-rebels” who reject ironic distance and “have the childish gall actually to endorse single-entendre values” (Wallace 81).

Admittedly generalizing the situation somewhat for conciseness’ sake, similar issues arise vis-à-vis beauty: After a century in which the notion of the beautiful was often ignored or actively eschewed, is beauty still worthy of pursuit within the “serious” art world? Among those who previously addressed such concerns are the Pattern and Decoration (P&D) movement. In the 1970s, artists such as Joyce Kozloff, Valerie Jaudon, Tony Robbin, Robert Kushner and Miriam Schapiro sought, among other things, to rehabilitate beauty from what they saw as macho art world attitudes that considered vivid color or ornamentation as weak and feminine, and thus not serious art. Using approaches as varied as installation, needlepoint and painting, P&D was controversial from the start, due in part to an overt emphasis on beauty in an art world focused on minimal and conceptual strategies. As Holland Cotter noted, “In America the movement became an object of disdain and dismissal. There were reasons. Art associated with feminism has always had a hostile press. And there was the beauty thing…[in that era] no one knew what to make of hearts, Turkish flowers, wallpaper and arabesques.”3

While attitudes against beauty are not as strong as in decades past,4 even today the art world seems to prefer such things be kept at a slight distance. Just as an encounter with an adult who radiates total, earnest sincerity can be a bit unsettling, a too “straightforwardly beautiful” artwork might set off one’s aesthetic B.S. detector in most contemporary galleries or art fairs. A viewer might seek out the artist statement to locate an ironic undercurrent or discursive complication embedded in the work’s subtext.

Such difficulty in appreciating unadorned artistic beauty suggests an approach to the contemporary beautiful. Perhaps beauty today operates in a manner similar to that of the sublime among 18th-century thinkers like Immanuel Kant. A sublime experience inspires awe and cognitive overload, but only if the experience is at a slight remove: The vastness of an ocean or mountain range threatens to overwhelm one’s thoughts, which is sublime; being in the path of an onrushing tidal wave or avalanche is not sublime, however, being instead an actual, direct threat. Analogously, classical beauty is direct in a way contemporary culture is no longer primed to accept, off-putting to a culture that prefers South Park to Masterpiece Theatre.5

I would argue that, in order to avoid what Wallace described as “the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs,” (Wallace 81) contemporary modes of beauty must come across obliquely in order to register as genuine aesthetic experiences. Today, not-quite-beauty6 serves a role that straightforward beauty once served in a culture less explicitly mediated and less meta than our own.

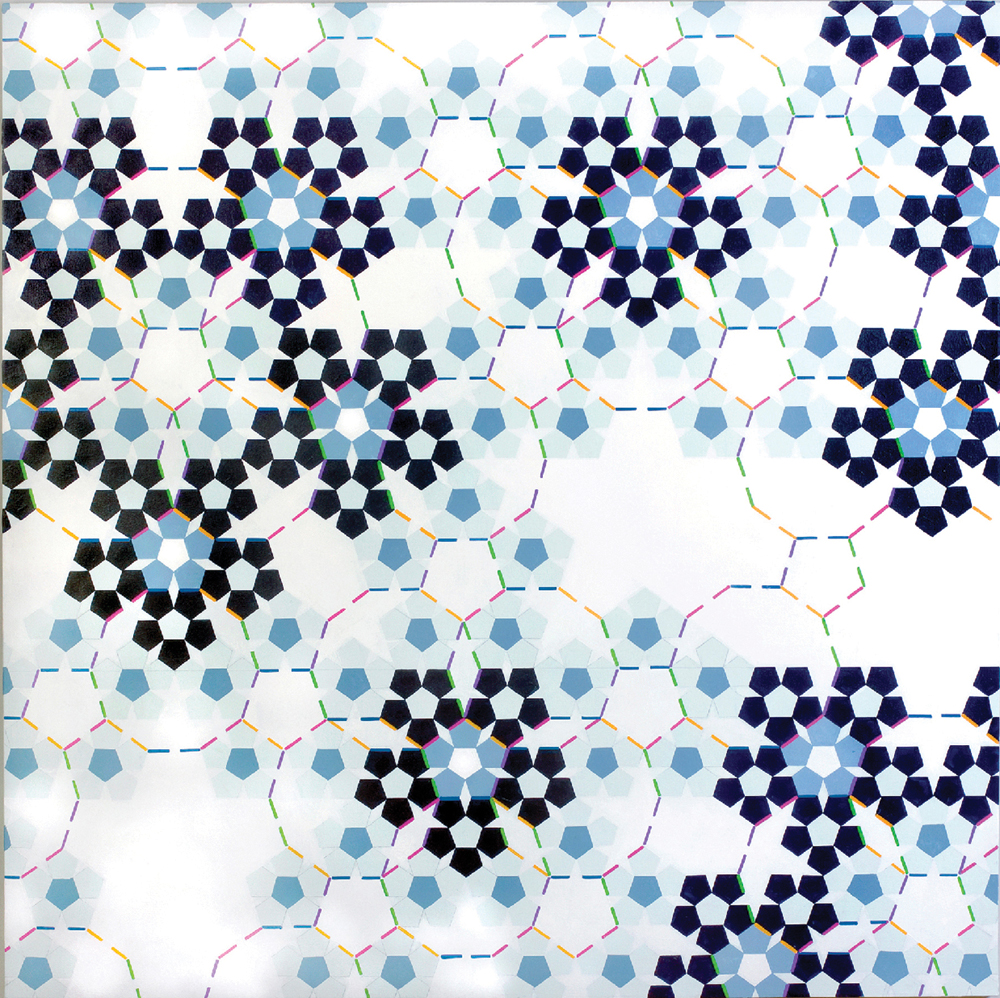

Clark Richert, QuasiShechtman, 2011-2012, acrylic on canvas, 70” x 70”. Photo: Valerie Santerli. Courtesy of the artist.

POST-BEAUTIFUL

A palatable contemporary beauty might be called the “post-beautiful”-beauty once removed-related to classical beauty in the way postmodernism was grounded in, was reactive to and superseded modernism. Resting on a post-ironic, sincere distance, post-beautiful tendencies are evident among many contemporary artists, though here I will focus on painters who deal with pattern, complexity and order while complicating those very qualities in ways both subtle and overt.

In 1909, Roger Fry wrote, “The perception of purposeful order and variety in an object gives us the feeling which we express by saying that it is beautiful” (Fry 21). However, in today’s era of big data and algorithmically predetermined sociality, the individual’s relationship to purposeful order is quite different than in Fry’s day-even taking into account the Fordist, assembly-line culture of his time. I would argue that in a culture of slick, binary-coded and focus-grouped order, a degree of painterly non-order serves a role similar to that of the beautiful, picturesque landscape in the early industrial era: It is not purposeful order that creates beauty in our day, but rather a respite from that very order.

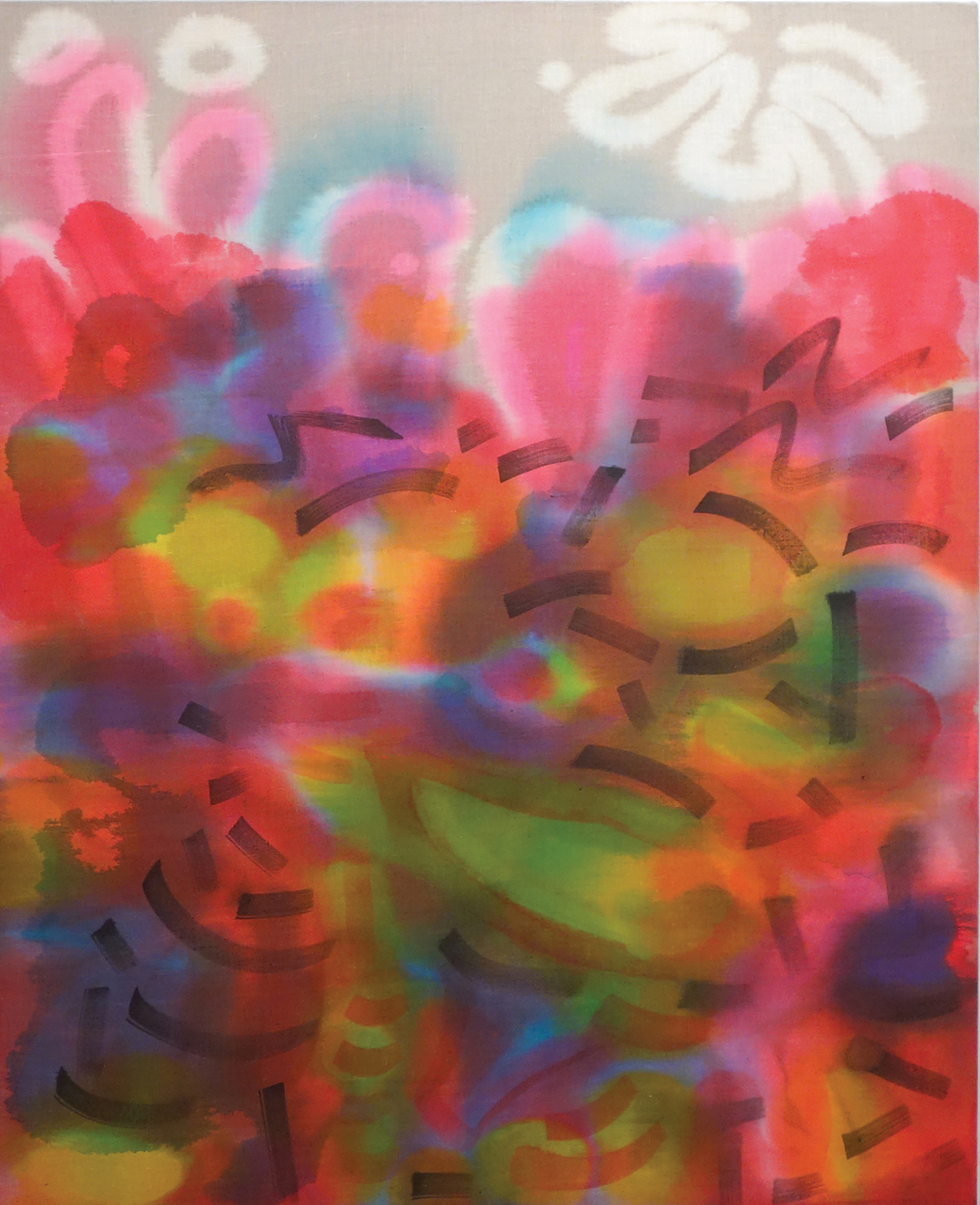

Iva Gueorguieva, Voyages in a Stone, 2012, acrylic, collage and oil on linen, 80” x 80”. Photo: Gene Ogami. Courtesy of the artist.

This brings us back to Pattern and Decoration. Whereas P&D artists sought to rehabilitate beauty and sensuousness in an austere art world, much recent painting suggests an interest not so much in sensuous decoration but rather in experiential deregulation, referencing then relaxing strict orderliness.7 If, according to P&D theorist Amy Goldin, the defining characteristic of a pattern is not repetition but rather “the constancy of interval,”(Goldin 50) many contemporary painters create works that hover on the edge of pattern, alluding to orderly interval and regularity without quite manifesting it.8 These artists have replaced Fry’s purposeful order and Goldin’s constancy of interval with what cultural theorist Paul Virilio has called “the interruption,” a break that inserts a bit of uncertainty into constructed systems (Lotringer and Virilio 109).

Among painters who privilege such experiential deregulatory interruptions are Allison Miller and Brian Porray. Miller’s painting Actor (2011) alternately creates, alludes to and disrupts at least three distinct DPI resolutions of grid, managing to be orderly in some sections and self-contradictory in others. The painting looks as if the grids and neon squares seek to mesh into an orderly pattern but must settle instead for incommensurate individuality, a playful ‘differend’ of orderly non-order. Porray’s ['''''5T4nD4RD C4nD13'''''] (2013) is a pictorially aggressive presentation of interrupted patterns, stripes and shapes, pushing toward outright discord. The articulated geometric form in the center looks like an attempt by Paul Klee and Thomas Nozkowski to build a geodesic dome: almost orderly, but not quite. Even here, though, is a fragmented kind of orderliness: Rather than regularity and pattern we get an irregular almost-pattern of shapes, each containing a section orderly in itself but chaotic in the context of the whole. Miller and Porray present work that moves toward orderly purpose but veers away at the last minute, creating a kind of skewed order that’s all the more era-appropriate-and perhaps (post)beautiful-as a result. Neither explicitly orderly nor disorderly, it’s the oscillatory, relational in-betweenness that counts: order plus disorder equals non-order.

Clark Richert’s painting Quasi Shechtman (2011-2012) takes a different approach to order and pattern. Richert works with what are called quasi-patterns, systematic sequences that appear to have regular intervals but are in fact structurally incapable of proper repetition. Unlike the endlessly repeatable tessellated squares of a checkerboard, Richert uses non-periodic tessellations, creating irregularly tiled almost-patterns that appear orderly at first glance while masking deep levels of asymmetry and non-order. If Fry could declare a century ago that beauty arises from purposeful order, today it is the almost-order of a work like Quasi Shechtman that prompts an emergent aesthetic experience to unfold from the differential tensions between pattern and quasi-pattern, between beauty and post-beauty.

Saira McLaren, Club Scene, 2013, fabric dye on raw linen, 45” x 36”. Photo: Mike Hein. Courtesy of the artist.

While Miller, Porray and Richert make works that hover on the knife-edge between harmony and non-harmony, the paintings of Iva Gueorguieva and Saira McLaren go in still different directions. Gueorguieva’s Voyages in a Stone (2012) goes straight toward overt non-harmony, presenting an all-over riot of cascading lines, broken structures and twisted forms, further interrupted by strips of linen collaged across the surface. Whereas Miller and Porray create pattern populations that seem as if they want to fuse but cannot, and Richert makes patterns that appear regular but are not, Voyages in a Stone seems at first glance to present pure, high-entropy optical chaos. However, a deeper look reveals an almost classically orderly compositional substrate, a large “X” that stabilizes the pandemonium. This hybridization of not-quite order/not-quite chaos updates and complicates Fry’s equation of beauty and order while lending the painting’s complexity an intriguing, on-the-cusp dynamic equilibrium.

After the explosive energy of Gueorguieva’s work, McLaren’s stain paintings present an alternate approach to the relationship between order and intuition. Where Gueorguieva paints overtly chaotic imagery with hints of underlying order, McLaren reverses that methodology. Club Scene (2013) comprises vividly colored, stained shapes and forms created with fabric dye. While fluid and intuitive, the painting shows attempts to impose order almost as an afterthought: Atop the picture plane a series of darker brush marks struggle to bound and clarify the hazy zones of color. The painting-a burst of colored penumbrae, their intensity nuanced by the softness of the post-painterly application-manages to be both intuitive and controlled, creating what Lacan called a place where the viewer can lay down her or his gaze,9 a momentary optical relaxation of order and imperative.

If in eras past beauty was innately equated with a sense of order, the situation has changed in contemporary times. Systemic order, whether perceptually, socially, discursively or algorithmically defined, can be very limiting. The introduction of a bit of non-order-an inoculatory injection of entropy-opens possibilities unavailable through strict regimentation, expanding the options an artist and culture can experience. Perhaps its is time to update Fry’s definition of beauty: The perception of purposeful non-order in an object gives us the feeling that we express by saying that it is post-beautiful.

WORKS CITED

- Fry, Roger. “An Essay in Aesthetics.” Vision and Design. NY: Dover Books, 1920.

- Goldin, Amy. “Patterns, Grids and Painting.” Artforum, September 1975.

- Lotringer, Sylvère and Paul Virilio. The Accident of Art. Cambridge, MA: Semiotext(e), 2005.

- Wallace, David Foster. “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S Fiction.” A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments. New York: Little, Brown, 1998.

NOTES

1. See Worringer’s claim that “natural beauty is on no account to be regarded as a condition of the work of art” (Abstraction and Empathy, 1906), or Kosuth’s statement that it “is necessary to separate aesthetics from art” (Art after Philosophy, 1969).

2. Articulated at length in Thierry de Duve, Kant After Duchamp. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998.

3. Cotter, Holland. “Pattern and Decoration: Scaling a Minimalist Wall with Bright, Shiny Colors.” The New York Times, January 15, 2008.

4. Critic Dave Hickey has written of the open hostility he received from artists, academics and critics incensed by his advocacy of a return to beauty. See The Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty, 2nd edition. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

5. Note that I’m not arguing for a contemporary sublime, but rather for a contemporary beauty that is similar in its experiential indirectness.

6. The term is ibid, Cotter.

7. Even proponents of technological regimentation are beginning to understand this: “What is greatest about human beings is precisely what the algorithms and silicon chips don’t reveal, what they can’t reveal because it can’t be captured in data. It is not the ‘what is,’ but the ‘what is not’: the empty space, the cracks in the sidewalk, the unspoken and the not-yet-thought.” Mayer-Schonberger and Cukier. Big Data. NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013, pp. 196-197. Correlatively, aesthetics emerged as a distinct branch of philosophy in the mid-18th century in part to continue investigation of the ambiguous areas of human experience then being left behind by Enlightenment rationality and the scientific method.

8. With thanks to L.A. critic David Pagel and NYC curator Fran Holstrom for suggesting some of the artists discussed in this article.

9. “The painter gives something to the person who must stand in front of his painting…Something is given not so much to the gaze as to the eye, something that involves the abandonment, the laying down, of the gaze.” Lacan, Jacques. Seminar IX: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. New York: W.W. Norton, 1978, pp. 101. Emphasis in original.

Jason Hoelscher is a painter, writer and educator. He is a professor at Savannah College of Art and Design and has exhibited his work in NYC, Paris, Berlin, Hong Kong and Stockholm. His writings have been published in ARTPULSE, Artcore Journal and various anthologies and conferences. Hoelscher received his MFA in painting from the Pratt Institute and is working on a PhD in aesthetics and art theory from IDSVA.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.