« Features

Occupying Corporate Hype: The Strategic Satire of The Yes Men

For over a decade, The Yes Men (Andy Bichlbaum and Mike Bonanno) have been engaged in an extended campaign of covert activism that is part performance, part satire and part fifth-column insurgency. In many cases, they do this through a sort of satire-by-agreement, posing as corporate executives and expressing ideas that are only slight exaggerations of their targets’ stated positions. In the process, they’ve managed to sell some truly ridiculous ideas to their audiences of industry insiders, including an algorithm for assessing when it’s desirable to trade human life for corporate gain (The Golden Skeleton program) and the SurvivaBall, a cumbersome portable cocoon designed to help the super-rich weather a major environmental collapse. In this interview, we spoke with Mike Bonnano of The Yes Men about their history, their thoughts on art and activism, and their current and future plans.

By Jeff Edwards

Jeff Edwards - I’ve seen you described as culture jammers, performance artists and even gonzo journalists. How do you describe yourselves and what you do?

Mike Bonanno - We’re primarily activists, but we’re also storytellers. We try to tell stories as creatively as we can, and we provide journalists with excuses to write about issues that they care about.

J.E. - You’ve been at this since 1999. How did you get started? Did you fall into being The Yes Men, or did you have a plan from the beginning?

M.B. - We fell into it; it happened to us. We put up a fake website for the World Trade Organization, and it was supposed to be a satire. To our great surprise, people thought we really were the WTO, and we got invitations to attend conferences as the WTO, so we started doing it.

J.E. - Over time, have you noticed a change in the way people and corporations respond to you after your ruse has been revealed?

M.B. - There hasn’t been a big difference over time. The usual corporate response is to very curtly say that they’re not responsible for whatever we say. They tend to try not to engage with us, because once they engage they’re dealing with us on our own terms.

The Yes Men posing as ExxonMobil and National Petroleum Council (NPC) representatives presented Vivoleum (a fictitious Exxon oil made with human flesh) to 300 oilmen at Gas and Oil Exposition, Canada's largest oil conference, held at Stampede Park in Calgary, Alberta, June 2007. Still from The Yes Men Fix the World, 2008.

J.E. - Your mix of deadpan performance and satirical imagery evokes comparisons with a pretty diverse group of artists who do institutional or cultural critique, including Andrea Fraser, The Guerrilla Girls and even Banksy. Do you ever think about your connection to such artists, and have you learned anything from watching them in action?

M.B. - We definitely are aware of what artists like that are doing. We enjoy it, and sometimes we’re inspired by it. We’ve come to realize that our practice is actually maybe even more closely aligned to theater than visual art. It’s taken us years to realize that.

J.E. - Whenever activist artists catch the art world’s attention, there’s always a danger of their being lured away from political engagement in favor of satisfying market and institutional demands. How do you feel about that, and when do you think that working with the art market becomes a betrayal of one’s political ideals and agenda?

M.B. - Well, obviously you have to figure out where you’re going to spend your time, which is limited. If we’re going to participate in art-world things, the question is: Can it subsidize some of the actions that we have planned? And if it can and if it’s worth it, then we do it. There’s a pretty crass commercial kind of logic to it. Sometimes with an art show you have to decide, what audience is it reaching, and how is it reaching them? There are many different things we do to try to do raise enough money to keep going, and some of them also generate a certain amount of exposure so that we can be evangelists for our cause.

J.E. - You’ve got an interesting relationship with the press. Media coverage of your actions is important for spreading your message to a wider audience, and my guess is that a lot of people in the news business like what you do, because it makes for good TV. How do you view your dealings with the media?

M.B. - We see what we do as collaborating, trying to feed the media good stories. For the most part, I think our relationship is pretty good. Journalists have a really hard job and a lot of work to do, and we try to make that job a little easier and give them some excuses to write the stories they want.

Halliburton SurvivaBall will save rich and corporate people from abrupt climate change. Production still from The Yes Men Fix the World, 2008.

J.E. - There’s a moment in The Yes Men Fix the World when a reporter confronts Andy after he’s posed as a HUD official in New Orleans. Andy tells him that that your subterfuge allows for ‘truth-telling where normally there would only be lies.’ What’s your response when journalists or people who have been taken in by one of your impersonations accuse you of unethical or harmful behavior?

M.B. - Well, we’ve never been accused by anyone of breaking the law, and we’ve never been charged with any crime. What we do isn’t illegal, so that’s one thing. The second thing is that it’s actually highly ethical. We immediately reveal the hoax. We assume the mantle of somebody in power so that we can have the voice that they’re normally given. They shouldn’t be given the right to that voice just by virtue of their wealth. That these established sources, these established voices are established merely because they’re from a large commercial firm is a problem. It’s a problem with the way we communicate in culture, and it’s the reason that we have a version of democracy that’s weighted so heavily toward big business. It’s not really democracy; it’s oligarchy. That’s the problem, and that’s what we’re trying to deal with.

J.E. - Based on what I saw in the film, it seems completely nerve-wracking to impersonate a corporate executive before a large and potentially hostile audience. After doing it so many times, has it become any easier?

M.B. - In some ways it is easier, because we know what’s going to happen. We know we’re not going to get arrested and won’t be subject to some kind of violent response. There are a bunch of things that we always expected in the beginning that turned out not to be true. After a while we were slapping our foreheads, thinking: ‘Of course we’re not going to be attacked. This is an environment where everybody’s wearing business suits.’ It’s really much more predictable than that.

J.E. - In The Yes Men Fix the World, you also talk a lot about how so many people have uncritically accepted Milton Friedman’s free-market gospel of greed. I’m also amazed at how posing as a trustworthy expert allows you to sell the most ridiculous ideas and images to your audiences (Gilda the Golden Skeleton and the Halliburton SurvivaBall being two great examples). Do you ever get discouraged about trying to fix the system when people seem so susceptible to the first person who comes along with a nice suit and a surplus of charisma?

M.B. - I think that kind of thing can be a challenge, but what we’re seeing now with the Occupy movement is that people are fed up, and they’re not going to take it anymore. They are rising up, and what it requires to change it is a mass movement. For a non-violent mass movement to succeed it has to have an incredible amount of support. Unfortunately, it’s pretty easy to do these things the violent way, you just need a relatively small force that’s really well trained. But that’s not what we’re interested in; we’re interested in doing this nonviolently, like they did in India to achieve independence, and like the Civil Rights movement did to change the system at the time. What we want to see out of Occupy Wall Street and the Occupy movement now is a way to build a new consensus that’s not founded on the idea of growth that comes with inequality.

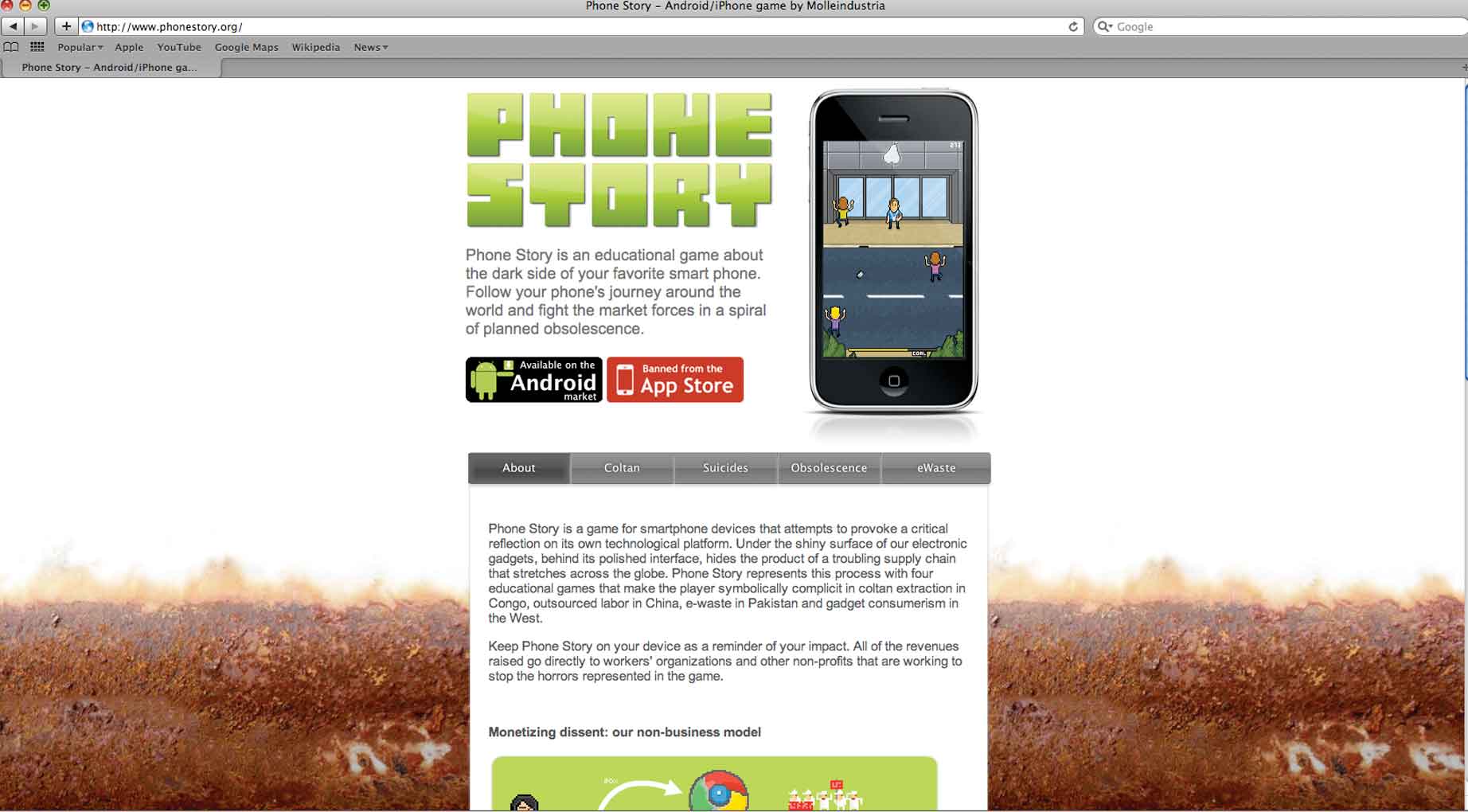

Phone Story, 2011, website screen shot. Phone Story is a game about the dark side of the smart phone industry. Created by Molleindustria in collaboration with The Yes Lab.

J.E. - Have you ever been recognized by one of your target audiences up front, before you’ve even had a chance to speak?

M.B. - We got recognized once by an audience in Calgary. One person in the audience recognized us and texted the conference organizers. They had to figure out what to do, which isn’t easy, because they had to remove their keynote speaker in the middle of the speech. It took them until we finished the speech to do it, and in the meantime it became a very funny scene, because they ended up dragging us off stage, which was great for our film. Now we actually try to make sure that they do find out, so that they can do something. If you have that intervention, it’s much more dramatic. For every story you need your protagonist and your antagonist, and if your antagonist shows up in the flesh and tries to do something against you, it’s much better.

J.E. - A few weeks ago, a stock trader named Alessio Rastani went on BBC and said that he dreams of the next recession because of the money he could make from it. A lot of people think the whole thing was a Yes Men hoax, though you’ve publicly denied it. Has your reputation led to other outrageous moments like this getting misattributed to you, and how do you think this particular incident reflects on you and what you have accomplished so far?

M.B. - We’ve definitely heard from other people who said they were inspired by what we did and who have done similar things, so we’re happy about that, and we’re inspired by other people doing amazing things. We just had a funny moment the other day where we were in a brainstorming session and Michael Moore showed up, and a bunch of the ideas we were taking about were things he did in the past, and he said, ‘Yeah, do it. This is how you do it; this is exactly the way.’ He basically said the same thing we always say, which is, ‘Yeah, rip us off.’ That’s what it’s all about. We ripped off other people so that you can rip us off. In a sense, ripping off is the wrong phrase because it’s just the way the culture’s always worked, as far as I can tell: through imitation, mimicry and repetition.

J.E. - While I was preparing for this interview, the ongoing Occupy Wall Street protests were constantly in my mind. You visited Zuccotti Park a week or so after the occupation started. Assuming the protests continue long enough, will you be doing any joint actions with OWS in the future?

M.B. - We’re a part of a group that’s called Occupy the Boardroom, and we’re part of working groups that are developing creative actions and creative communication. We’re part of a large, diverse group of people who are all working toward the goal of creatively communicating the messages of the movement. There are several different groups we’re working with and several different initiatives we’ve been a part of. But we don’t claim authorship of any of it; we’re just part of many people doing these things.

J.E. - With the Yes Lab, you seem to be moving into a new phase in which you’re networking with a lot of other activist groups to pool resources and ideas. How did this come about, and where to you want to go with it?

M.B. - Basically, we recognize that it’s more effective for us to work with organizations that have ongoing campaigns. Little actions that create some amount of publicity are often most effective if there’s a campaign that they tie into, so our entire effort now is in training more Yes People through this action-based training program that we call The Yes Lab. If we work with an organization to create an action that supports one of their campaigns, then the people in the organization can go on and do it again themselves. It’s sort of that ‘teach a man to fish’ kind of idea.

J.E. - Recently, I read about Phone Story, a Yes Lab iPhone game dealing with the monstrous working conditions that exist all along the consumer electronics supply chain. Apple pulled it from its app store almost immediately, and you responded by reformatting it for Android. The game pushes activism into a really new type of venue. Are you planning any other activist projects in novel settings?

M.B. - Right now we’re not really planning anything, but rather working with different organizations. In the case of Phone Story, we worked with a couple people who had the idea of putting that together and who were associated with Friends of the Congo. Primarily it was Molleindustria, the video game designer, and also one of Andy’s former students who came together with Friends of the Congo. But really what we’re doing there, and what we do in all these cases, is support campaigns that we think are good. They have to be something that helps with social or environmental justice. That’s kind of where we’re at right now.

J.E. - Do you have a vision of what you’d like the world to look like when your work is done, or do you prefer to stay focused on the specific issues you’re dealing with at any given moment?

M.B. - I think you can’t avoid having an idea of what things should look like if you’re participating in something like the Occupy Movement. Ideally, we would have a system that isn’t based on the idea of maintaining runaway growth. There are certain core principles that have to be changed in order to make this system work. One is that we can’t base everything on the idea that we can continue to grow, because there’s an endgame to that. We have to take these very basic, very simple ideas and enact them in a way that creates a fair and more just society. One version of that is anarchism, which is ground-up government. There are aspects to that kind of thing that are really viable; for example, participatory budgeting, which is in use in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and has worked incredibly well for shifting the priorities of the community. When a community actually has to vote about what they want their money to go to, typically they do support things like education and infrastructure, typically they do enact a more democratic and fairer way of distributing funds. Those sorts of steps can be taken in the right direction, but also we could do a complete overhaul. The question is the realisticness of actually doing a total ground-up restructure. It’s difficult because of all the powers that would oppose that, that have sunk costs in the existing system.

J.E. - Finally, if you were going to hang it all up tomorrow and had a chance to go for the proverbial ‘one last big score,’ who would be your dream target, and what would you like to do?

M.B. - I think right now, there’s got to be a way to tackle the problem of the influence of money over government, so in a way the dream target would be the lobbying and banking systems that are implicated with one another. The problem is that the corporate world is like a hydra. You cut off one head and it grows three more, so we’re not going to single out a corporate target. That doesn’t help fight the system. It works as a tactic, but it doesn’t work as a strategy. The dream is really to establish a different kind of system that’s more just and sustainable. There’s a scene from the Charlie Chaplin movie The Great Dictator where he plays a Jewish barber who basically steps in to Hitler’s place and makes an announcement that changes the course of history. We need an opportunity like that to come along. That sums it up right there; that’s the kind of chance we need, and we don’t really see it on the immediate horizon. I think what we can invest our hopes in right now is mobilizing as many people as possible to occupy everything, so we can turn the tide.