« Features

Painting Time

In 2013, at the opening of “Painter Painter,” the Walker Art Center’s first exhibition of contemporary painting in over a decade, Jan Verwoert ended his memorable talk with a demonstration: a simple baseline on a Roland TP 3 Base Synthesizer entering a feedback loop. The filter the sound passes through begins to oscillate, and its self-oscillation amplifies the sound into uncanny electronic bird chatter. The point of Verwoert’s self-proclaimed “gimmick time” was to illustrate the loopy, rhythmical time of painting. Time, according to the German critic, is not linear in painting. In the experience of being lost in the work, lost in painting, it is not so clear where the beginning, or the end, is. Rather than proceed from point A to point B, time in art does not follow a line from clear intention to predictable end but unfolds from “the retrospective discovery of the production of the beginning of what you did.” In other words, “The end is set by the return of a beginning. The beginning that returns in the end is not the same beginning of the white canvas.”1

Verwoert’s second point pertaining to abstract painting was its adjacency to other spheres of cultural production and interaction: from the discotheque to the domestic, the house of fashion to the city. In what follows, I take these two ideas, loopy time and adjacency, and shift phase: rather than focus on the process of making, the way Verwoert does, I consider temporality in painting as a subject, adjacent to other negotiations of time passing, of commemorative practices and history. In particular, I am intrigued by the odd temporality Derrida calls “hauntology.” He theorizes the “logic of the ghost,” which “points toward a thinking of the event that necessarily exceeds a binary or dialectical logic, the logic that distinguishes or opposes effectivity or actuality (either present, empirical, living-or not) and ideality (regulating or absolute non-presence).”2 Irrepressible traces of past events haunt the present, spectral and elusive. Such traces are particularly persistent in cases of trauma, whether individual or cultural, when the past erupts into and effectively ruptures the present. The three painters whose work I focus on in this essay grapple with history, with time past that refuses to stay put: Andrea Carlson, Chris Willcox and Julie Buffalohead. All three tell stories that unfold in degrees of adjacency to current events, that is, history in the making; all three work more figuratively than abstractly and are fully engaged with the history of representation.

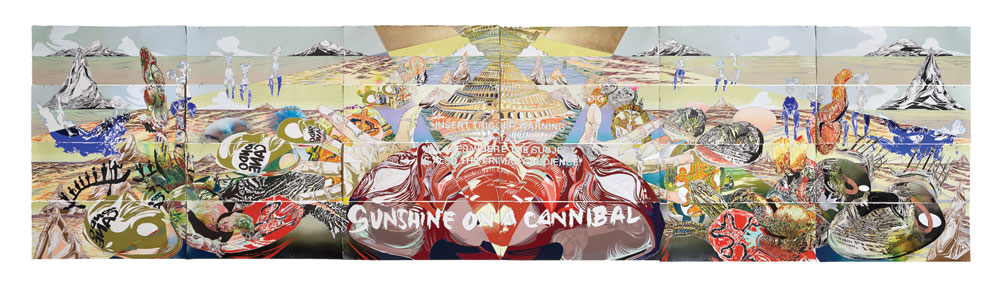

Meticulously crafted, Carlson’s work revolves around North American history. Often, her paintings feature first-contact shorescapes and are rich in allusions to the pictorial history of representing cross-cultural encounters. Sunshine on a Cannibal (2015), first exhibited as part of Minnesota’s fall 2015 biennial “superusted” at The Soap Factory, intertwines colonial legacies of exploitation and misrepresentation suffered by indigenous cultures with allusions to the history of European art. Vaguely “tribal” masks of the artist’s invention float above a vast seashore dominated by a vertically mirrored tower of Babel. Body prints reminiscent of the marks left by Yves Klein’s human paintbrushes hover above the scene, while the words “Mondo Cane” reference a 1962 film by Paolo Cavara, Franco Prosperi, and Gualtiero Jacopetti, which Klein saw (and much disliked for its portrayal of his work) briefly before his death. Anecdotes, myths, imaginary masks and the ghosts of actual events are woven into a precise geometry made up of 24 small rectangles that combine into a mysterious painting of epic proportions. Carlson’s visual story is not for the faint of heart: “INSERT TRIGGER WARNING HERE IN CASES WHERE THE SUBJECT IS ALSO THE PRIMARY AUDIENCE,” the painting warns in bold letters.

Andrea Carlson, Sunshine on a Cannibal, 2015, mixed media on paper, 4’ x 15.’ Courtesy of the artist.

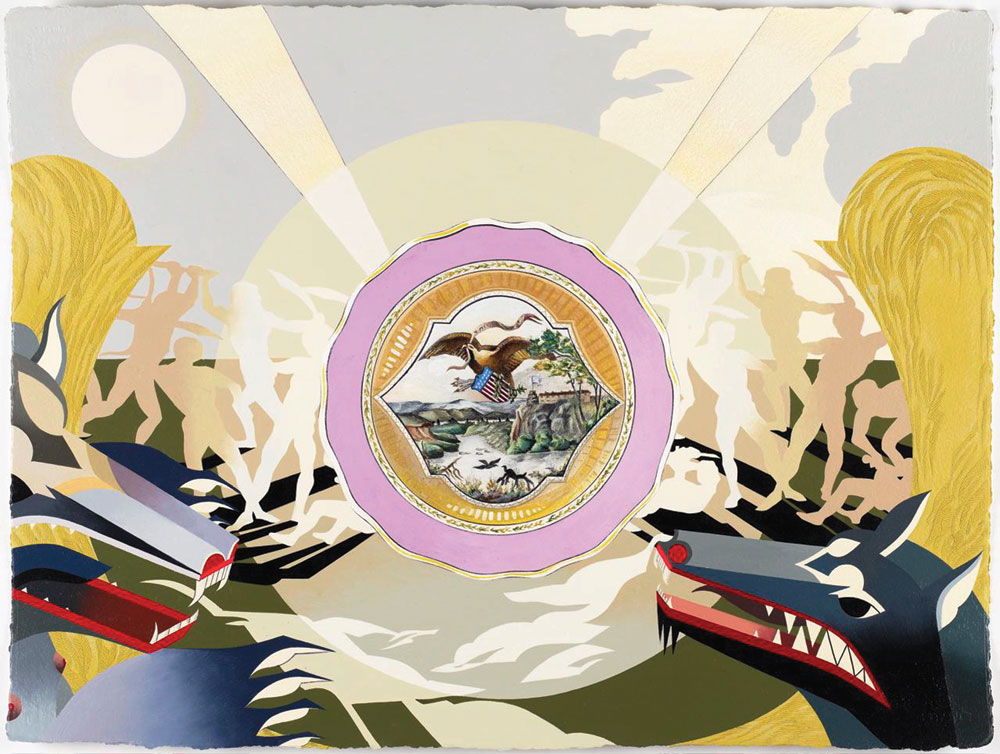

Having the subject of genocide rendered palatable in countless tales of putative European heroism while erasing indigenous suffering is also the topic of Truthiness (2006), a painting currently on display at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (Mia) as part of the group exhibition “Arriving at Fresh Water: Contemporary Native American Artists from Our Great Lakes.” Truthiness features a painted plate at it center, made in Germany in 1865 to commemorate Fort Snelling, a European outpost at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. A sacred site for the Dakota, the floodplain at the Bdote, the two rivers’ confluence point, housed an internment camp between 1862 and 1863, where countless Dakota died from illness, starvation and exposure to the cold. The sentencing for the largest mass execution in American history, on Dec. 26, 1862, also took place at Fort Snelling before 38 Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, Minn. This tragic history is erased in the commemorative plate, which shows a bald eagle in flight, a banner in its beak, the paraphernalia of nationalism in its talons. The plate with its entirely unsubtle symbolism is part of Mia’s collection.

In Truthiness, Carlson shows the plate amidst a battleground where silhouettes of warriors fight. In the foreground, two large canines of large proportions wait for an “unholy feast, where those who ate are taught symbols meant to shroud the truth.”3 Unapologetically political, Carlson’s work engages with the history of painting, commemorative practices and strident misrepresentations of indigenous cultures. In her work, museums and their collections function as retention landscapes that preserve and mediate the events considered sufficiently relevant to pass on. Objects, like the plate, are nested in stories that often double as cultural narratives, which are never innocent and not over: They continue to unfold in the present.

Willcox paints places. Like Carlson’s, her work is rooted in the past, both in the tradition of representing landscapes in paint and in the histories that haunt the places she paints, where ghost-like horses and humans navigate terrains suspended between then and now, here and there. Layers of acrylic shimmer like semi-transparent strata of sediments. They, too, keep time but blur any semblance of certainty. The past bleeds into the present, as if to embody Derrida’s “logic of the ghost.” What emerges from Willcox’s paintings is a queer temporality, disorienting and out of step with the linear progression of straight time.4

As if a case in point, the title of her upcoming 2016 exhibition “The Beginning (Again)” signals a return to a starting point, a case of “loopy time” in Verwoert’s words. The exhibition brings together a series of large-scale acrylic paintings on paper, collectively titled “The Story,” with smaller, more recent oil paintings on wood panels. The scenes that unfold in the larger work primarily picture the land around Minnesota’s Fort Snelling as a landscape of aftermath. They bear witness to what no longer can be undone.5 Having walked across that scarred land, Willcox seeks to make visible an elusive residue, the spectral traces of histories that still, mysteriously, affect us in the present.6 On the wooden panels, palette and paint change. Luminous pink glows underneath dramatic drips of oil. Scenes seem wrested from the sheer materiality of paint. Here, Willcox moves away from specific locations and toward structures of broader symbolic significance: a cabin, a bridge, a bunker, a church. They speak to basic human needs for shelter, safe haven and reliable passage. At times, they are unfinished or on the verge of dissolution, as if their presence was precarious. It is.

Chris Willcox, The Deserter, 2015, oil on canvas, 19” x 23.” Photo: Rik Sferra. Courtesy of the artist.

In Willcox’s latest paintings, animals gaze back at us: a white wolf, a pale mare. Derrida, seeing himself in his cat’s implacable gaze, muses, “Thinking perhaps begins there.”7 Again. The paintings embrace such speculation. Though steeped in the past, they harbor an anticipatory quality, a potentiality not quite on the horizon.8 This sense of a not-yet becomes most tangible in a series of almost encounters: The Deserter, a figure astride on a caribou, pauses in a wintery wasteland, head slightly turned. A meeting seems imminent but not unavoidable. In The Messenger, a rider approaches on a bridle-less horse, arms folded impassively. A low sun backlights their approach, the glare suggesting a squint, a mirage, a maybe.

Willcox’s messengers, deserters and witnesses step out of linear history and into an epic time of myth and stories. Far from ancient, this landscape comes alive, too, in Buffalohead’s paintings, where strange encounters unfold between fact and fiction, the political realities of Native American life in 21st-century United States and the timeless world of stories. Mostly devoid of backgrounds, her scenes unfold on monochrome planes, ranging from rich reds to deep blues to cool grays. Thus, Buffalohead situates her characters, human and non-human, in a space and time apart yet adjacent to the familiar, defined only by the mood evoked by color.

Unlike myth, which Roland Barthes famously described as “frozen, purified, eternalized,” Buffalohead’s stories inhabit a curious present; they are ongoing. In Merry Feast (2012), a girl wearing a set of antlers shares a meal with a raccoon, her white dress matching the tablecloth. A fox observes the two, ears folded back, mouth agape, standing on its hind legs and gesturing as if in futile protest at such domestic cross-species intimacy. The painting suggests a slight shift in perception, a realignment that looks at both mundane moments and politically charged encounters through the lens of stories. In Stampede (2014), included in a retrospective of the artist’s work titled “Coyote Dreams” at the Minnesota Museum of American Art in summer 2015, Fox and Rabbit lie on their backs and manipulate a cast of shadow puppets with their paws: a cowboy, guns drawn, postures next to buffalos, a skunk, squirrel and bikini-clad cliché of an “Indian princess” in a feather-head dress. Not only does the painting cast doubt on the stereotypes and reduce them to mere shadow puppetry, it suggests a different unfolding of temporality. Far from occupying a mythical space outside of time, the paintings invite an epistemological reorientation in the here and now.

Julie Buffalohead, The Stampede, 2014, acrylic, ink, and pencil on lotka paper. Courtesy of Bockley Gallery.

Time, then, loops in different ways in the three artists’ work. Buffalohead’s paintings embrace the fluidity of an oral tradition of storytelling. Ordinary interactions turn strange in their proximity to the world of stories. This particular adjacency arises from indigenous conceptions of temporality, where causality does not abide by the dictate of linearity but is ever emergent and, like the tricksters that playfully haunt Buffalohead’s work, unpredictable. In Carlson’s paintings, history is what it is-and then it isn’t, to paraphrase Verwoert. Her work dislodges familiar accounts, switches perspectives and creates complex pictorial histories that occupy a space adjacent to official historiography and remembrance. Her work unfolds in fragments that congeal to reveal and question powerstructures before turning them upside down. Always, her work insists that the way we tell history, remember and commemorate past trauma, changes experiences in the now. The past is not over but haunts the here and now. Willcox’s work, especially the paintings that make up “The Story,” hovers in a space between past and present, refusing the logic that insists on separating then from now, here from there. Time becomes fluid, and each return promises a beginning unlike the one that came before. Emerging from the past like specters, her characters, human and non-human alike, anticipate different encounters. “The Beginning (Again)” embodies a longing for “another way of being in the world and time, a desire that resists mandates to accept that which is not enough.”9

Notes

1. Jan Verwoert. Opening Day Talk for “Painter Painter.” Curated by Bartholomew Ryan and Eric Crosby. Walker Art Center, February 6, 2013.

2. Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx. Trans. Peggy Kamuf. New York, London: Routledge, 1994. 78-79.

3. Andrea Carlson, wall didactic for Truthiness. Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Gallery 255. November 2015.

4. For ideas on “queer time” and futurity, see José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia. The Then and There of Queer Futurity. (New York and London: New York University Press, 2009. 10.)

5. Willcox’s fascination with places steeped in tragic history continues: how might places hold such memories? In previous bodies of work, Willcox traced the fates of early Antarctic explorers and researched the almost century-old battlefields of the First World War in France and Belgium.

6. See also the international network of artists and scholars called Mapping Spectral Traces. http://www.mappingspectraltraces.org/

7. Jacques Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am. Translated by David Wills. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008. 29.

8. José Esteban Muñoz writes, “a potentiality is a certain mode of nonbeing that is eminent, a thing that is present but not actually existing in the present tense.” Cruising Utopia. The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York and London: New York University Press, 2009. 9.

9. José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia. The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York and London: New York University Press, 2009. 96.

Christina Schmid is a writer, critic, teacher and curator. She works at the University of Minnesota’s Department of Art, where she teaches contemporary practices and critical theories. Her essays and reviews have been published both online and in print, in anthologies, journals and digital platforms, including Artforum, Flash Art, Foam Magazine, afterimage and mnartists.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.