« Editor's Picks, Reviews

Pivot Points in Contemporary Art. A selection from MOCA’ S Collection

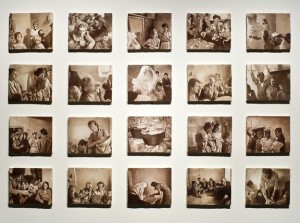

Adrian Paci. The Wedding, 2007. Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, Photo © Steve Brooke

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in North Miami presents “Pivot Points I & II,” two significant exhibitions that offer a reflective look at its permanent collection. Both shows are curated by Bonnie Clearwater, MOCA’s Executive Director and Chief Curator, with support from the museum team, especially Curatorial Assistant, Ruba Katrib.

The exhibitions reveal the criteria used by the institution to configure its collection, seeking to include core works in the evolution of contemporary art. Rather than selecting pieces according to style, materials and historic-artistic periods, MOCA prefers focusing its attention on conceptually and methodologically interrelated pieces, which reflect key moments in the history of art. This prudent curatorial criterion makes it possible to collect artworks with points of convergence, encouraging rich dialogue between artists and works from different contexts and historic periods.

Analyzing the proposal of each of the artists participating in these exhibitions would be an interminable task, especially considering that most of the work is of exceptional quality and constitutes key pieces within the MOCA collection. Thus, we will use a few representative pieces as examples, allowing us to comment on the curatorial criteria that have guided these two exhibitions.

“Pivot Points I: Defining MOCA’ s Collection” assembles works which reflect MOCA’s own history as an institution as well as that of its collection. These are works produced by internationally-recognized artists and groups of artists who may or may not live in Miami. These are works that exemplify key moments in their careers, and at the same time signify turning points in the progression of contemporary artistic production. For this reason, we could not overlook Ed Ruscha’s photographic books, published between 1963 and 1978, which were the first items donated to MOCA in 1994. Ruscha, in the manner of Duchamp, photographed the Los Angeles landscape as a “readymade,” creating a series of 16 books which were widely distributed throughout the world and which signified a new direction in the “artist’s book” category.

Pivot Points I will be shown until May 11 at MOCA headquarters (Joan Lehman Building, North Miami). Exhibited, in conjunction with the collection of Ruscha books, are pieces by other prominent artists, such as: Jennifer Steinkamp, John Bock, Dennis Oppenheim, John Baldessari, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Thomas Hirschhorn, Mark, Handforth, Francis Alÿs, Ed and Nancy Kienholz, Jorge Pardo, Bert Rodríguez, Richard Artschwager; and a group of 14 creators assembled by Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno in “No Ghost Just a Shell.”

“No Ghost Just a Shell” is a group multimedia project that appropriates a Japanese manga character named Annlee, which was purchased by Huyghe and Parreno in 1999 for only 400 dollars from a company that designs characters for comic books and animated film. They “freed” Annlee from her original function, and together with other artists provided her with new roles. The character comes alive in videos, posters, sculpture, painting and books. The name of the project comes from the manga film, “Ghost in the Shell,” (1995). However, unlike the film, Huyghe and Parreno’s project suggests that a work of art, can only exist if the artist has endowed it with the vital energy of a concept or an idea. This project reflects on aspects such the authorship of work in contemporary art, the relationship between an artist, his oeuvre and the spectator, and the multiplicity of interpretations that artistic creation currently proposes.

John Baldessari’s piece, “Three Red Paintings,” is based on fragments of movie scenes appropriated by the artist in order to construct other narratives. Baldessari places these fragments on a red background and covers the characters’ faces with paint. The viewer can observe the apparent conversation between a man and a woman in one of the works; in another, he witnesses an arrest and in the third, he can observe a hand holding a gun. The three pieces are arranged in such a way that their frames touch each other. Not being able to identify the faces covered with paint, forces the observer to refer to his own visual experience in order to find threads that will allow him to develop a narrative for the piece. By evoking memories, Baldessari plays with the meaning of images and the beholder’s interpretation of them.

“Diorama,” (1997) by Thomas Hirschhorn questions how the placement of an object within an exhibition hall can predetermine its valuation and interpretation. “Diorama” is an enormous display cabinet reminiscent of those used in natural history museums, in which objects of diverse workmanship are displayed, some made of aluminum foil, cutouts of reproductions of works of art, etc. The author thus indicates that no matter what is displayed, merely placing it within the context of a museum exhibition hall, grants the object a hierarchy, and legitimizes it as being worthy of being exhibited and presented to the public at large. “Diorama” reflects on the roles of curators and art historians as those entrusted with recognizing and legitimizing creations, identifying relationships between works of art and assessing their historic significance.

John Bock’s piece, “Zero Hero,” (2003) deserves special mention. The work which was presented at the 2005 Venice Biennial and during Art Basel Miami Beach in 2006 was inspired by the story of Kaspar Hauser, an adolescent, who after growing up in a dark cell for 17 years, deprived of all human communication and contact, suddenly appeared in Nuremberg in 1828. “Zero Hero” is an enormous installation made up of: objects used in the performance which gave rise to this project in 2003, documentation of this process and a video created specifically for the installation. Bock, assisted by other actors, reproduces in the video the traumatic experience of this individual who was civilized in a violent manner.

The second part of the exhibition entitled, “Pivot Points II: New Mythologies,” is being presented at the MOCA Goldman Warehouse from April 12 through June 28. This show assembles works that explore the paths contemporary artists take to create their own mythologies, or that reflect on the role of myths from various perspectives, periods and cultures. Participating creators include: Matthew Barney, Jose Bedia, Louise Bourgeois, William Cordova, Tracey Emin, John Espinosa, Phillip Estlund, Luis Gispert and Jeffrey Reed, Christian Holstad, Isaac Julien, Guillermo Kuitca, Mariko Mori, Adrian Paci, Jorge Pantoja, Raymond Pettibon, Ali Prosch, Matthew Ritchie, Jason Rhoades, Ann-Sofi Sidén, Saul Steinberg, Barthélemy Togo, Kyle Trowbridge, Tunga, and Michael Vasquez.

The tour starts with an installation by the Cuban artist, José Bedia. It is comprised of two enormous panels, covering most of the wall space in the room, on which the artist has arranged elements that allude to the emblems, flags and monograms of shipping companies. In the center of the room, an enormous canoe appears full of rice, sugar and corn meal. On a nearby wall, a figure with large arms desperately extends his extremities towards a ship. With “Cargo Cult,” (2005) Bedia refers to a phenomenon which occurred amongst cultures in the South Pacific when they became dependent upon provisions carried by cargo ships, chiefly American, during World War II, and stopped producing their own products. Little by little, these groups also started altering the belief systems and worship patterns they had used to attract prosperity and well being, worshipping instead the freighters that brought them commodities. With this work Bedia shows how First World nations establish power over less-developed nations by sponsoring dependent relationships.

The Swedish artist, Ann Sofi Sidén, in “Station 10 and Back Again,” (2001) uses surveillance cameras to record the activity at a fire station in Norrkoping, Sweden over several weeks. The result is an installation in which she exhibits objects related to the work of firemen next to 18 monitors that display scenes from the daily lives of these men. These individuals, usually perceived as heroes, on this occasion appear carrying out activities which are far from heroic. They appear bathing, exercising, eating, watching television or waiting to be summoned to put out a fire. The visitor is transformed into a voyeur who, as time goes by, is seized by the tension that at any moment the alarm will sound.

Ali Prosch in his video, “Not My Mama,” (2004) delves into the hidden terrain of feminine violence and aggression, questioning stereotypes surrounding the role of maternity and its “innate” protective instincts. Prosch presents, as the protagonist of “Not My Mama,” a feminine monster who emerges from a lake and, unable to control her own instincts, savagely destroys her own eggs.

The Albanian artist, Adrian Paci, mythifies the value of memories in “The Wedding” (2007). Paci, whose work is characterized as dealing with the political situation in Albania and his own experience as an immigrant, presents a polyptych comprised of 20 square fiberglass panels, which imitate a texture similar to stone, and on which he has reproduced with tempera, as though it were an al fresco painting, scenes from a traditional Albanian wedding which took place at the beginning of the nineties. The festive nature of the scenes contrasts with the vagueness of the strokes and the rough texture of the support. The scenes which consist of fragments of memories appear to become diluted, diffused. An immigrant’s life is closely tied to memory. Over time, recollection loses clarity in the mind of the immigrant, but at the same time it turns sublime, idealized and mythified.

Although the title, “Pivot Points,” may initially appear a little ambitious, especially if we consider the fact that it relates to the collection of a fairly new museum, this thought is immediately dispelled when we visit both exhibitions. These exhibitions make clear this institution’s commitment to growth by sponsoring responsible dialogue, reflection, analysis and interpretation of the artistic phenomena of our time.

Raisa Clavijo: Curator and art critic. BA in Art History (University of Havana, Cuba), MA in Museology (Iberoamerican University, Mexico), Former Chief Curator of Arocena Museum (Mexico). Editor of Wynwood. The Art Magazine.

Filed Under: Editor's Picks, Reviews