« Features

The Biennialization and Fairization Syndrome. Interview with Paco Barragán

“Art history hasn’t shown much interest in the social and economic conditions of art and its relation to the history of the art market.”

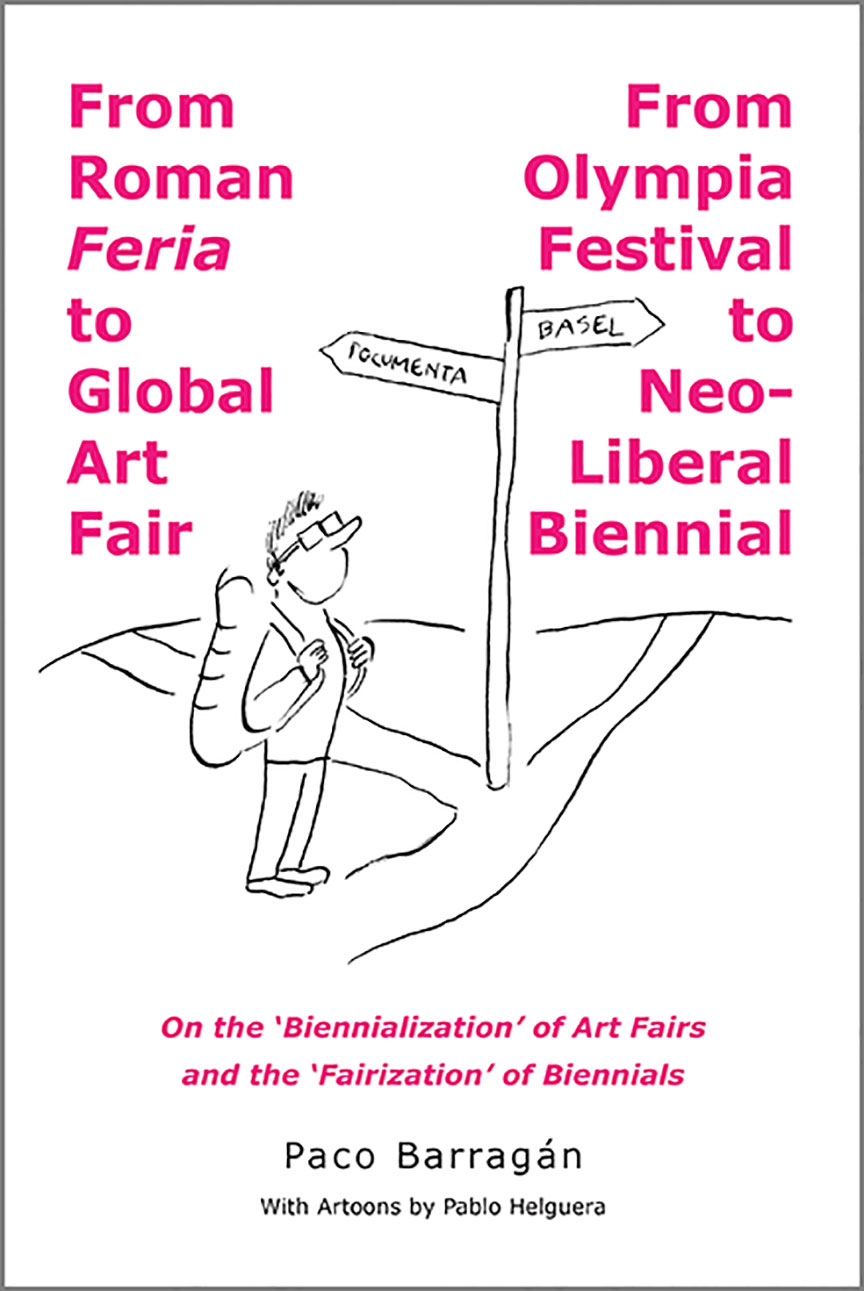

In his latest book From Roman Feria to Global Art Fair, From Olympia Festival to Neo-liberal Biennial: On the “Biennialization” of Art Fairs and the “Fairization” of Biennials, curator and writer Paco Barragán challenges the dominant narrative about the genealogy of art fairs and biennials. Read on and you will discover that Latin America had at some point the highest concentration of biennial exhibitions, what went wrong with ART COLOGNE, and why a truly comprehensive and balanced study on the phenomenon of fairs and biennials has yet to be made.

By Michele Robecchi

Michele Robecchi - Ever since I met you, when you were working at the Valencia Biennale in 2002, I was struck by your interest both in art and in the mechanisms that define the art system in equal measure. Where do you think this fascination for the most political and structural aspects of art and its market ultimately comes from?

Paco Barragán - Yes, you’re totally right! And actually, this interest crystallized in November 2020 in the consecution of my International PhD at the University of Salamanca (USAL) titled “Narrativity as Discourse, Credibility as Condition: Art, Politics and Media Now.” In my thesis I analyze the complex, contradictory and controversial relationships between that which is artistic and that which is political. We all accept eagerly that the sphere of the political (understood from Hannah Arendt’s perspective) determines the artistic. Let’s recall how monarchs, kings and aristocrats “manufactured” reality through history painting. But the opposite is even more the case: how the artistic prefigures and configures the political. Yet the way from art to politics is poorly acknowledged. Both politicians and audiences receive images that stem from painting, films, theater, novels, and so on. Seeing is a constructed process and although some people may not experience these works of art directly, they do indirectly via television, Internet and social media. Many of the virtues and vices displayed in the political arena like ambition, power, generosity, authority, philanthropy and leadership derive directly and indirectly from art. They are based on social, political and psychological myths and values from the artistic field, as Murray Edelman so elegantly argued in his wonderful book From Art to Politics: How Artistic Creations Shape Political Conceptions. In other words: art manufactures the images that define our world. As a catalyst, it provides images and creates situations that are strange, provocative, utopian, engaging or radical, and by doing so it ends up configuring the political regime. According to Edelman “art simply serves as a floating signifier into which political groups read whatever serves their interests and ideologies.”(1) Art is, as Ernst van Alphen rightly states in Art in Mind: How Contemporary Images Shape Thought, not only a “historical product” but also a “historical agent” with a “performative” function in whose realm “ideas and functions, the building stones of culture, are actively created, constituted, and mobilized.”(2) Of course, not all that the art world produces has an equally educational or aesthetical feedback. Sometimes the artifacts, images and processes generated by the artistic realm cause great havoc and alarm in society. The Dana Schutz affair is a perfect example of how artistic freedom can offend certain groups. The idea of l’art-pour-l’art is fascinating but also very naive: art never exists in a vacuum, it acts against, reacts to and re-enacts the political, ideological, social, economic and psychological conditions of society. And as such, for me understanding the overall framework that conforms the art system is mandatory for understanding art itself!

Paco Barragán, “From Roman Feria to Global Art Fair, From Olympia Festival to Neo-liberal Biennial: On the ‘Biennialization’ of Art Fairs and the ‘Fairization’ of Biennials.” Artoons by Pablo Helguera. Published by Artium Media, ARTPULSE Editions, 2020.

M.R. - Your first book, The Art Fair Age (2008), explored the phenomenon of art fairs. Your second book titled From Roman Feria to Global Art Fair, From Olympia Festival to Neo-Liberal Biennial: On the “Biennialization” of Art Fairs and the “Fairization” of Biennials investigates fairs and biennials, and how these two formats have dominated the way art has been presented over the past two decades. In it you note how literature about some fringes of these pivotal platforms has been scarce. Why do you think that is?

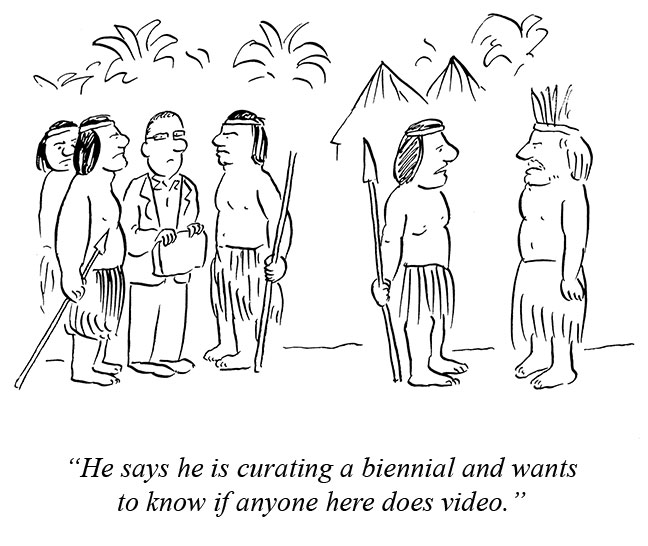

P.B. - I think we have two issues here at play of an art historical and a philosophical nature. Art History with capital letters is basically the history of the artist as genius, artistic movements, genres and the aesthetical appreciation of beauty. Let’s recall that most studies and research about art and its relation to the market stem from the sphere of economics (think of cultural economics like John Michael Montias, Peter Spufford and Clare McAndrew) or sociology (Raymonde Moulin, Olav Velthuis, Filip Vermeylen and Alan Quemin). Still today art history hasn’t shown much interest in the social and economic conditions of art and its relation to the history of the art market. A second element that explains this lack has a philosophical background: The very idea of the art market, that is art as a commodity, has always created a kind of uneasy tension in the artworld in general and academia in particular. Let’s recall Winckelmann, Schiller, Kant, and even Marx and their distinction between play and work, contemplation and art production and the capital idea in art and art history of “disinterestedness.” If you combine these two aspects you understand why there are hardly books about art fairs (market, commodification), but not why there are still relatively little books about biennials (art history, disinterestedness). And while the art fair represents the wrong side of art history, it’s incomprehensible that the biennial that stands for the right side of art history—if we think with Pablo Helguera’s cartoons—has so little bibliography. Just think that the classic book of the Venice Biennale is still Lawrence Alloway’s The Venice Biennale 1895-1968: from salon to goldfish bowl written back in 1969! And what about documenta? There are six books about documenta, but most of them in German and only one is bilingual German-English, edited by Michael Glasmeier and Karin Stengel, titled 50 Jahre/Years documenta (Archive in Motion) published in 2005. This is weird. Only between 1955 and 2005 there were some 35,000 articles according to Karin Stengel and Friedhelm Scharf in their essay “Press Poliphony: A History of Documenta-Criticism.” By now this could easily amount to 100,000! Closer in time we have The Biennial Reader: An Anthology on Large-Scale Perennial Exhibitions of Contemporary Art edited byElena Filipovic, Marieke van Hal and Solveig Øvstebø in 2010, but it consists of a series of essays and articles, it’s not a book that provides a historical perspective of the biennial. And if we add to it that most of the biennial literature is Eurocentric and hardly contemplates, for example, the rich history of biennials in Latin America, then there is a lot of research to be done.

I wrote a book about the history of art fairs and biennials for another important reason. I’m aware that theorists that are interested in art fairs don’t write about biennials and those interested in biennials don’t consider art fairs, as they understand these as separate spheres. But these are, as I say, “the old ways”: we need a less biased approach to counteract the “experience economy” and “culture industries” that have pervaded all spaces of contemporary life and also the artworld and its structures. This black and white approach (art fairs-bad versus biennials-good) is no longer valid as it’s unable to apprehend the large scale of greys: how art fairs and biennials have morphed throughout history, producing the so-called “biennialization” of art fairs and the “fairization” of biennials. In this sense, my book is not only about the history of art fairs and biennials but also about their heterogenous status in today’s neo-liberal system.

M.R. - It is common practice for fairs and commercial galleries to hire curators and art historians. Fairs also have significantly incremented exhibition projects-I’m thinking of Frieze Masters and Parcours. Do you think this distinction between “good vs bad” as you said, still stands?

P.B. - As you can see it’s very interesting what has been happening historically with the art fair. The modern art fair or artist-frame-to-frame-model was organized by artists; the contemporary art fair or dealer-booth-and-alley-model at the end of the 1960s was organized by dealers; and the global art fair or curator-open-space-model has been organized by corporations like Merchandise Mart, Art Basel’s MCH Group and so on.

And with it came also the shift in the profile of the art fair director: no longer dealers but art critics (Amanda Coulson and Marc Spiegler), curators (Omar López-Chahoud, Neville Wakefield, Andrea Bellini, Francesco Manacorda) and even art historians (Noah Horowitz). In short: art fairs have recruited profiles from other sectors of the art world that were not specifically connected to sales and the art market. Besides all those curated sections and panels and seminars—what I have called the “biennialization” strategy of the art fair—art fairs also attracted a new profile of manager with art historical knowledge, who is not afraid of the art market and promoting business. It’s fascinating in a way. But biennials are also de facto sophisticated sales platforms.

So, you can’t easily say which side is on the right side of art history. And in the end, it only reflects the complexities and contradictions proper of today’s neo-liberal society.

M.R. - In your book you pinpoint the 1990s as a pivotal moment in the proliferation of biennials. This was a time where many institutions worldwide figured it was more effective to concentrate financial and logistical efforts on one periodical big event rather than investing in the program of an institution few people would visit. Cut to two decades later, many of these biennials no longer exist. What, in your opinion, went wrong?

P.B. - Yes, the 1990s was neo-liberalism in full swing with the advent of low budget air companies, cheaper transports, tourism, the naissance of city branding and so on. In short: the so-called “experience economy.” And within this whole “experience economy” biennials and art fairs have become the perfect tools of soft power, as Joseph S. Nye keenly would have argued, in the tough competition for attention.(3)

As you know, founding a biennial can respond to the want for “being modern” and attract tourism, but it can also respond to a political decision, which is very often the case. And since a biennial—unlike a museum—is a perennial event that happens every two years, it is a much more eagerly awaited affair that has achieved, as you know very well, cultural event status. Due to its periodicity, events like the Venice Biennale or documenta (or even Art Basel) have this aura that a museum lacks because it’s always there!

Yes, you’re right, many biennials have disappeared or are simply in bad shape. One of the best examples I know is the Valencia Biennial: it lasted four editions! It was a political decision by the Secretary of Culture Consuelo Ciscar from the Partido Popular, Spain’s right-wing party, to hold a biennial and put Valencia on the international map, and it was equally a political decision by her successor Esteban González Pons, member of the same political party, to get rid of it. Valencia had a €5 million euro budget, but the local scene was against it as they considered the money should be invested in the local artistic infrastructures. If a biennial doesn’t have the support of the local art scene and addresses its necessities it simply ends up failing. We can quote artist and Third Text editor Rasheed Araeen here confidently: “The purpose of a biennale anywhere in the world is first to address the needs of its own local or national constituency, its own art community, and if this constituency is not taken into consideration whatever one does will fail.” This was precisely the reason why the Johannesburg Biennale disappeared after its second edition, and this was also the reason why the local art scene in Gwangju created the Anti-Gwangju Biennale because-as Korean curator Jiyoon Lee recalled-they didn’t feel represented by the “junk from the West.” Very often it’s a political decision that underlies the foundation of a biennial and very often it’s equally a political decision that forces the termination. And, of course, these political motivations can respond in full or in part to a general economic recession and budget cuts in education and arts.

M.R. - You mentioned the Valencia Biennale, an event you obviously have a great degree of insight on. I remember visiting the first edition and being perplexed at what felt like a very enjoyable cultural event but with little connection to the context in which it took place. Why do you think that was? Laziness? Parochialism? Both?

P.B. - I think it was a mix of parochialism, the desire for “being modern” in the sense of up-to-datedness, newness, progress and coolness and of course the firm idea of competing for international high-end tourism. In short: the biennale was another tool in the strategy of global city branding. And although the biennale only lasted four editions, it really put Valencia on the global map. Time Outdid a special magazine on Valencia and also architect David Adjaye did a special program on the BBC. And today everyone knows about Valencia. But is it very different with Istanbul, Gwangju, Sydney or Shanghai? Most of those biennales have reproduced the Eurocentric model and brought in high-end Western curators in order to attract international art audiences and press coverage.

M.R. - This brings me to another point you make in your book—the tendency of biennials of invariably picking up from the same pool of curators, resulting in the replication of the same model over and over again. Whilst I understand the reasoning—international experience and reputation are evident assets-ultimately you seem to imply that the blame for this lack of imagination lies mostly at the curators’ door rather than the organizers.

P.B. - Well, basically it’s a mix of factors here at play. On the one hand, we have local politicians and local elites that use the biennial to brand their city and their own agendas and recur to established curators that have been doing the rounds: first Harald Szeemann, Jan Hoet, Rudi Fuchs and the like, and more recent people like the late Okwui Enwezor, Charles Esche, Massimiliano Gioni, Nicolas Bourriaud, Hou Hanru and Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. In this sense, you see there is a pool of curators with international status that for a local politician or local corporation can guarantee international visibility and international press coverage for their city with their sole presence. Deep down it’s a very parochial attitude that reveals an enormous inferiority complex among local politicians and elites, wanting to be accepted by the mainstream. And this is what has brought with it the kind of sameness and uniformity that is proper of most biennials in terms of curatorial proposals and the repetition of a same group of artists.

Furthermore, those curators are brought in because with them on board it’s much easier to have certain high-end artists participating and certain branded galleries, collectors and foundations paying production costs, transport, installation of the artwork and guarantee the presence of the artist.

Finally, as you can see from most biennales, all the topics are revolving around the same fashionable issues related to post-colonialism, multi-culturalism, globalization and a kind of bland institutional critique that ended up being institutionalized critique. All the World’s Futures, Viva Arte Viva, How to (…) things that don’t exist, May You Live in Interesting Times, Beyond the Future, Between Idea and Experience, Fever, A Grain of Dust a Drop of Water…. The titles are clear examples of this kind of curatorial art speak.

M.R. - The Venice Biennale stopped selling art in 1968. Art Basel was born in 1970. Do you think there is a correlation between these two events? Or do you have the feeling that fairs, regardless of the evolution of biennials, were bound to boom anyway?

P.B. - We consider the past with the eyes of the present, id est, anachronistically. We think grosso modo that art fairs are sales platforms while biennials and museums are not. But that has never been the case. Most of the exhibitions, starting with the Roman Old Masters blockbusters in the 1600s that later were replicated in Paris, London, Amsterdam and Berlin were sales exhibitions. The exhibitions organized by the national Royal Academies or salons were also sales exhibitions. Most museum exhibitions at the end of the 19th and deep into the 20th century were sales exhibitions.

In this sense, the fact that the Venice Biennale between 1942 and 1968 functioned like an art fair with an official trader, Ettore Gian Ferrari, who charged 15% for the Biennale and 2% for himself for any artwork exhibited at the show that he was commissioned to sell, was not new, it simply continued anterior sales models. We have to bear in mind that the art fair had already earlier sales precursors like the Renaissance pand (1470), the Baroque kermis (1630), the salons organized by the French Academy (1667), the Paris World Fair (1855), the Salon des Independents (1884), the Impressionist exhibitions (1784), the Munich Glaspalast Austellungen (1886) and especially The Armory Show (1913).

But yes, there is an interesting coincidence between the discontinuation of sales at the Venice Biennale in 1968 and the advent of the contemporary art fair at the end of the 1960s. Sales were an important part of the funding of the Venice exhibition, which was chronically underfinanced. The advent of the May 1968 protests also affected the Biennale and the Giardini. “Venice,” writes Vittoria Martini, “was invaded by thousands of students who believed the Biennale and the city itself represented all they were fighting against at the time: institutions overrun by rampant capitalism encouraging the commercialization of art.”(4) The protests also put an end to the awarding of prizes, and these were not reinstated until 1986.The prizes had always been surrounded by intrigue and corruption according to Alloway. Especially notorious was art dealer Leo Castelli, who campaigned incessantly with the international committee members to obtain the painting award for the artists he represented, like Rauschenberg and Lichtenstein. Dealers’ influence was felt strongly at the Biennale during these years, and the changing political and sociological climate crystallized around that time in the advent of the contemporary art fair organized by dealers: ART COLOGNE in 1967 and Art Basel in 1970. The student struggle against capitalism and bourgeois society paradoxically contributed to the advent of the art fair!

Did sales end at the Venice Biennale? It’s obvious that sales have mutated into more sophisticated forms, but Venice is still one of the major platforms for consolidating artistic careers. Art dealing, concluded Alloway, is symbiotic of the modern Biennale. And let’s recall the words of former Art Basel director Lorenzo Rudolf when he decided to launch Art Unlimited in 1999: “Our biggest competitors were suddenly not the other art fairs but the biennials. We had surpassed the other art fairs, but suddenly we saw this phenomenon of the biennial turned into a market event; and even if it wasn’t official, next to each art work you would find the dealer and he was selling it.”

M.R. - You mentioned The Armory Show—arguably the oldest event of this kind. It managed to successfully survive different decades but lately it seemed to have suffered from the competition of global art fairs “invading” its turf. What do you think will happen in the long run? History alone doesn’t seem to help if you fail to adapt to an evolving landscape.

P.B. - The Armory Show in 1913 is a fascinating case whose feats and merits haven’t been properly acknowledged. There are of course sectorial studies, but when we put it in a larger context, we can’t but be surprised how it presaged the “contemporary art fair” model of the 1970s like ART COLOGNE and Art Basel and even the “global art fair” of the 1990s like ARCOmadrid, Frieze or Art Basel Hong Kong (ABHK).

Organized in 1913 at the premises of the Armory of the National Guard’s 69th Regiment on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, under the directorship of Arthur B. Davies, it introduced most European artistic movements to the American audience, from Romanticism to Impressionism to Cubism. It was a comprehensive survey show that wanted to present the history of modern art. Let’s recall that The Armory Show was a sales event organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS) in the manner of a huge exhibition, with around 1300 works by 300 American and foreign artists, tightly hanged on the walls in 18 partitioned spaces, held between February 19 and March 15. The driving force behind The Armory Show was formed by a small group of people consisting of Arthur B. Davies, Walt Kuhn, Elmer Livingston MacRae, Walter Pach and John Quinn. Artist Walter Pach, the trans-Atlantic liaison who had lived in Paris since 1907, acted as the exhibition’s sales broker.

The Armory Show is what I call the “modern art fair,” characterized by the artist-frame-to-frame model. On a less grand scale than the Salon des Indépendants, it was much more international and presented for the first time a massive show of European and North American art. This is what contemporary art fairs, like ART COLOGNE and Art Basel, would set out to do in 1967 and 1970, respectively! The show travelled to the Art Institute of Chicago and to Boston’s Copley Hall: 271,326 visitors attended the show in total! It was a curated show: the American section was curated by Davies and the European avant-garde by Pach. The Armory Show became a perfect example of how the modern techniques of marketing and publicity would help promote the International Exhibition of Modern Art at the 69th Regiment Armory. Kuhn, Pach and Davies hired the services of journalist Frederick James Gregg as public relations representative, paying him the incredible amount of $1,200, subscribed to the Henry Romeike press service, printed 50,000 catalogues, four pamphlets of 5,000 copies each, a color poster, made lapel buttons, a set of post cards to advertise the show, and even made photographs of the show both for sale and for free distribution to the press. This is something not even ART COLOGNE and Art Basel were able to perform in the 1960s and 1970s on such a scale and with such sophistication! Even from a tax perspective it was absolutely modern: we should not forget that artworks that were less than a hundred years old had to pay a sales tax in America and The Armory Show took up the “duty-free” fight for living art to the Congress, completed successfully by John Quinn, who acted as legal adviser and won its revocation. More than forty years later Katherine S. Dreier asked herself: “What happened that this exhibition [The Armory Show] should have made such a lasting impression?” It brought avant-garde art to provincial America and it created slowly but steadily the major and most important market for art: first for Old Masters, later for the “New Old Masters,” the Impressionists, and much later for Cubism. And the shock waves of The Armory Show paved the way after the Second World War for New York as capital of the art world. It was discontinued for a series of complex reasons, but the most relevant was the rude repudiation from the camp of the artists, and not only those that were angry because they hadn’t been invited to exhibit their work, but also from factions within the AAPS. The radicalism of the European avant-garde caused a double shock: It crudely showed American artists their provinciality and it opened up the American market to foreign artists. This, the American artists considered a kind of betrayal by Arthur B. Davies, Walter Pach and Walt Kuhn. The Association had been brought to life to foster and defend the interests of its members, but the “American” acronym had been neglected in favor of foreign artists.

Today’s The Armory Show was originated in 1994 as the Gramercy International Art Fair at the Gramercy Park Hotel. When it moved in 1999 to the 69th Regiment Armory, the fair was renamed “The Armory Show” in homage to the legendary 1913 fair. Obviously, the situation is totally different now. I think it’s a mix of factors that we’re dealing with. The Armory Show never got really off the ground and I’m sure you recall that some of the most important galleries in New York never participated. I think that the mighty gallery structure in New York has become a kind of “permanent art fair” that worked for many years against the foundation of an art fair. Additionally, there hasn’t been a really first-rate art fair in the whole of the United States, not even Art Chicago in the 1980s when it was booming. It’s only when Art Basel decides to open a branch in Miami that the major American galleries decide to participate. And the same happens later when Frieze opens in New York. For some reason American art fairs failed where Art Basel and Frieze succeeded. And I think that The Armory Show will have difficulties competing with its European counterparts (especially now that there are many global art fairs like FIAC, ARCOmadrid, Art Basel Hong Kong) and, secondly, because the whole art fair business has been put into question. So, no, history alone is not enough to guarantee success! But for me The Armory Show of 1913 is an extraordinary and really outstanding event that revolutionized the art world and turned the tables in favor of America.

M.R. - In the book you also discuss extensively the role of ART COLOGNE. When it was conceived in 1967, Germany was still split in two. You would think that the reunification in the 1990s would pave the way for the fair to become even more central but the exact opposite happened.

P.B. - The case of ART COLOGNE, which I analyze in depth, is a really fascinating case of what not to do. ART COLOGNE had all the ingredients to become successful: official support and the collector’s base. And yet it didn’t succeed because of artistic, structural, organizational and psychological reasons that are outlined in the book and are too long to explain here.

But one of the main reasons was that it was not really internationally oriented. Important foreign galleries such as Leo Castelli, Sidney Janis and Ileana Sonnabend were not admitted to the fair. Rudolf Zwirner’s philosophy was: why let them participate if we can buy the works from them and sell them directly to our clients? That was a very bad decision that together with the fact that only the members of the Verein progressiver deutscher Kunsthändler (Association of Progressive German Art Dealers) could participate at the fair would favor Art Basel in the long run. Since Daniel Hug stepped in as new director in 2008, ART COLOGNE has become a much better fair. But it’s not at the same level as Art Basel or Frieze.

I sincerely think that what happens to ART COLOGNE is very symptomatic of the German art scene: it’s too much inward-looking. There are no key museums like MoMA or Tate Modern, there are no German curators in charge of international biennials or curating relevant international exhibitions. And while Berlin is a very important city in terms of the international presence of artists, the gallery scene is fragile. On top of that, if you look at German museums, unlike what happens in the US or UK, there are hardly any foreign directors working in Germany, which is very, very strange. It’s a fact that the artworld only travels to Germany every five years on the occasion of documenta!

M.R. - I remember ARCOmadrid at the turn of the century being possibly the only fair where Latin American art was solidly represented. Do you think the birth of Art Basel Miami Beach (ABMB) in the mid-2000s contributed to erode this position?

P.B. - Yes, absolutely! Art Basel Miami Beach (ABMB) stole in 2001 ARCOmadrid’s crown as the platform par excellence for Latin American art. Until then ARCOmadrid was the sole destination for Latin American art galleries. Lorenzo Rudolf, who was Art Basel’s director between 1990 and 2000, was the mastermind behind Basel Miami. Many art professionals think it was Sam Keller, but it was not his idea. Rudolf left in 2000 and Keller was at the helm of Basel Miami from the very first edition in 2001. And he really did a good job, but it’s important to respect the facts.

Now, what is even more interesting and less known is that ARCOmadrid’s director, Rosina Gómez-Baeza, had already by the beginning of the 1990s the idea of launching a sister fair in Miami. We should recall that at the beginning of the 1990s many important American galleries like Max Protetch, Robert Miller, John Weber and Donald Young were attending ARCOmadrid and not ART COLOGNE or Art Basel (Basel was facing serious problems by then) and they had suggested, according to Gómez-Baeza, to open a fair in USA “somewhere nice and warm” away from cold New York. Additionally, in 1992 when Rosina did a presentation of ARCOmadrid in Los Angeles, various Latin American galleries harked on the same idea. As such, in the beginning of the 1990s Gómez-Baeza proposed to IFEMA, ARCOmadrid’s governing body, the opening of a fair in Miami. But the answer by IFEMA was that her job was to bring people to Madrid, not to Miami! Of course, this was a very shortsighted decision that has had very negative consequences for ARCOmadrid. The major Latin American art galleries and also major USA galleries prefer Art Basel Miami Beach (ABMB) to ARCOmadrid. Madrid has become a second option. And this is the story of how ARCOmadrid lost its positioning of thefair for Latin American art!

M.R. - Art Basel Miami has taken the idea of collateral events to a new level. The first time I visited it in the mid-2000s I remember counting 18 fairs around town. (And you were involved with one—PhotoMiami). Why do you think Miami proved to be such fertile soil for this proliferation?

P.B. - Well, as you know, ARCOmadrid’s “experiential model” was functioning amazingly well and I’m sure you recall that the-who-is-who of the artworld in the end of the 1990s was in Madrid: from Glenn Lowry to Alanna Heiss to Barry Schwabsky, Okwui Enwezor, Hou Hanru and Hans-Ulrich Obrist. The mix of panels, curated sections, performances, international collectors, art curators and other art professionals combined with the numerous openings and parties in Madrid made ARCOmadrid clearly different and more festive than any other fair at the time. This is what cultural critic Miguel Mora had to say about it on Sunday 16, 1997 in the Sunday edition of El País: “They are all well-dressed; the gentlemen with expensive shoes and the ladies in high fashion clothes; but the shadows under their eyes give away the exhaustion caused by an overloaded program: performances, parties, museum, art fairs, conferences and after-hours, then they begin all over again.”

This is what Sam Keller later implemented in Art Basel Miami Beach (ABMB). Keller had visited ARCOmadrid many times and so he had a first-hand experience. Additionally, Rosina Gómez-Baeza told me that Keller visited her in Madrid with his entire team learning what she had been doing that made the fair so attractive.

Then of course, Miami had a mix of elements to offer that made the city irresistible. In the first place, the timing in December was perfect with no other big fair competing. This is very important (this has been for example one of the major failures for many years of ART COLOGNE). Secondly, the amazing weather made a trip to Miami enormously attractive, while New York, London and Berlin were freezing. Many people took the trip to the fair as a small holiday! Thirdly, the whole hotel and club scene in Miami also added glamour to turn the city in a preferred place for swinging (after) parties. Fourth, the private collectors like the Rubells, the Margoulis and the De la Cruz among others who opened their private houses and held shows at their exhibition spaces. Fifth, Miami is traditionally the city where many Latin American millionaires and collectors have a second residence and spend their holidays in December. So, the city was ripe for a fair that could have a strong Latin American flavor and become the first fair for Latin American art outplaying ARCOmadrid. And sixth, the fact that Miami is also a kind of tax haven adds an additional layer to its success.

Now, if you take all these elements together combined with the fact that in the meantime The Perez Art Museum and the ICA Miami have joined the scene, the result can’t be more spectacular. I remember to have visited Miami in 1997. From an artistic perspective it was a desert. People went, but to visit Gianni Versace’s mansion on Ocean Drive! The change Art Basel Miami Beach (ABMB) has brought to the city has been simply spectacular. And ABMB has pushed ARCOmadrid’s “experiential fair” model to stratospheric limits. I remember that at some point around 2008 or 2009 I counted 30 parallel art fairs to Basel Miami! Never in the world, and not even in Basel or in New York, has a fair created so many parallel events. It’s madness! What I always say to people that haven’t seen it with their own eyes is that they need to travel to Miami at least once. You can’t really imagine it if you haven’t experienced in the flesh!

M.R. - Should you be the director of an art fair, what would you do to make it stand out?

P.B. - Besides PhotoMiami I also worked for CIRCA Puerto Rico, as you know. But these were small fairs and one can “curate” the fair and talk to the participating dealers about what kind of art to bring. This is impossible with big fairs like Basel or Frieze. The “experiential model” that was invented by Rosina Gómez-Baeza at the beginning of the 1990s and that brought about the Global Art Fair (GAP) with curated sections, panels, parties, parallel museum exhibitions, focus countries, after-hours and so on (and that later Art Basel, FIAC, Frieze, The Armory Show and the rest of the fairs have copied) has worked very well for more than twenty years. But in times of economic crisis like now, it doesn’t seem to work. Art fairs are expensive because their fixed costs are very high. This “experiential model” went hand in hand with the strong presence of the curator with curated sections and even public projects especially conceived for the fair, like Frieze Projects. But today art dealers want more sales and less background noise. And I think that art fair directors for some reason have failed in building a larger collector’s base and finding new collectors. Many dealers are complaining that they meet hardly any new collectors at fairs.

So, if we take this into consideration, this is the art fair’s biggest challenge, and not conceiving new panels or flashy curated sections. The clients of the art fair are the galleries, and it needs to find collectors for them. In other words: back to basics!

There will always be big fairs like Art Basel and Frieze, but I think that smaller fairs should cater more to their local and national galleries and audiences. With COVID-19 art fair directors, like museum and biennial directors, have seen themselves overwhelmed. And in this case, they have been overreacting and organizing tons of OVR activities that have caused “OVR-fatigue.” In times of crisis, you have to offer your clients knowledge, but all these activities have caused too much noise and too little knowledge. In short: for me it’s not about doing something that makes you stand out as an art fair, but more about enlarging the art fair’s collector’s base and help dealers sell art and meet new potential clients.

M.R. -You just mentioned the viral emergency. Years ago an attempt was made to launch the first digital art fair. It didn’t work out, mostly because technology wasn’t there yet. (I believe it was called “Exhibition Art Fair” and only lasted for two editions). Within the current climate, do you think that experience would have made more sense or fairs, like biennials, are at their best only when visitors have the opportunity to interact with each other and see art for real?

P.B. - Yes, you’re right. Art Basel America’s director Noah Horowitz was in charge, if you recall. It didn’t work out then and it wouldn’t work out today. The viewing experience is very poor and lacks imagination. It’s practically no more than a website with the price tag!

But let’s be honest: The artworld never made the shift from 1.0 to 2.0. It’s all very basic. If you take a good look most art magazines and websites work in the traditional paper-mode manner, id est, a text with an accompanying image uploaded on their website. There is hardly any intertextuality: It’s either a video or it’s a written text with photographs.

Are you asking me whether the digital is taking over the real experience? On the contrary, we will see two kinds of spectators from now on: 1) the OVR users who will have to content themselves with the digital experience (complementing it with visits to local and national exhibitions) and 2) the “realists” that will want to experience the real artwork. In other words: the art world will become more elitist, like it was before the 1990s, and international travelling will become more exceptional (unless there is a vaccine soon). Can you imagine going to see the Sydney Biennale and having to stay forcibly quarantined during two weeks in a hotel paid by you for finally visiting the biennale for a week? Not too many people will accept that!

It will also mean that real experience will have even more “aura” than before! As of today, online viewing experiences as the Art Basel one are extremely deficient. No wonder people ended being fed-up with the excess of OVR-activities. Comparing the digital experience with the real experience of an artwork is like comparing virtual sex to real sex: while virtual sex is good for an emergency it will never replace real sex!

M.R. - Your book casts important lights on a time when cities until then considered peripheral in an admittedly West-centric art discourse, like Istanbul, Havana, Tirana and Johannesburg, made an attempt to take center stage. Why do you think Istanbul seemed to have fared better than most?

P.B. - Istanbul is the perfect example of the neo-liberal biennial model: it has since its inception in 1987 applied the same recipe of international curators: Hou Hanru, Jens Hoffmann, Adriano Pedrosa, Charles Esche, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Nicolas Bourriaud, just to mention a few-and artists with an international reputation, the corresponding local quota and the vague themes that are normative in this kind of large-scale international event. And, last but not least, the biennale is organized by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (IKSV), a non-profit and non-governmental organization established in 1973 by Dr. Nejat Eczacibasi, owner of the Eczacibasi Pharmaceutical and Investment Holding.

As Dany Louise rightly explained, “The IKVS foundation can therefore reasonably say to be aligned from inception with the economic interests of the parent company, international destination marketing, the globalizing economy and the desire to be associated with Western development concepts.” So, matters of education, developing a local art scene or attending its needs are not on the agenda.

Despite the complex political moments that Turkey is traversing (with the migration crisis, the role in the civil war in Syria, the rampant authoritarianism and religious conservatism, and the repression of women) in both the 2015 edition by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and the 2017 edition by Elmgreen and Dragset, political art was absent.In other words: the biennale functions as a de facto high-end marketing event for specialized art audiences.

M.R. - Do these shows necessarily have to display a political angle in order to work? In 1976 Carlo Ripa di Meana organized the Biennial of Dissent. It was the first time Venice was going for a thematic approach. It was criticized precisely because it was felt the political angle was too facile. Most importantly, it was dismissed as a weird approach. Interestingly, from the 1900s onwards devising biennials with a theme, even better if political, became the norm.

P.B. - Yes, the years between 1968 and 1976 are fascinating years in the life of La Biennale, but probably underrated among international art audiences and still “strange.”

To me perennial events like the Venice Biennale or documenta are important because they represent the Zeitgeist of our time: they should convey what is good, utopian or radical art and give us as citizens an idea of the challenges of society. But most biennials are imbued with the vague, ambiguous, “new institutionalist” and “soft” curatorial themes that became customary in biennials since Okwui Enwezor’s Johannesburg Biennale of 1997. As I said before, they all basically revolve around easy, marketable topics or, straightaway, non-concepts. These are the typical biennale themes of which Julian Stallabrass would have said: “They can be stretched to include just about everything and thus mean very nearly nothing.”

M.R. - 1972 is generally acknowledged as the year when documenta changed forever. However, you pin down the 1990s/early 2000s as a further moment of reconfiguration of the show.

P.B. - If Harald Kimpel talked about the exhibiting versus commissioning phase, I see three clear periods: 1) the modernist art phase (1955-1968), 2) the star curator phase (1972-1997) and 3) the global art phase (2002-today).

The first phase was under the helm of Arnold Bode and Werner Haftmann and focused on exhibiting modern Western art. It was characterized, on the one hand, by Arnold Bode’s Inszenierung, which were innovative but not in the appropriate way. As a graphic artist and trade fair designer, his displays overplayed the artwork, relegating it to almost an irrelevant function. And as such, all the four documentas had an irretrievable art trade fair air. On the other hand, Werner Haftmann continued with Alfred Barr’s formalist reading of art history and abstraction as lingua franca. For this reason, even Robert Rauschenberg’s Bed (1955), which had been selected by MoMA’s Porter A. McCray and shipped to Kassel for the documenta2(to be held in 1959), was squarely rejected because it went against Haftmann’s narrative that “art had become abstract.”

The second phase starts with Harald Szeemann, who inaugurates the “star curator” era with well-known art professionals like Jan Hoet, Rudi Fuchs and Catherine David, and exhibits exclusively Western contemporary art. From a philosophical and geo-political perspective, and contrary to what the title of the exhibition enunciated, documenta was an exclusive Eurocentric and later Euro-Americancentric event. Walter Grasskamp defined it as “selective Eurocentrism.”Germany, Italy, France and, from the second documenta on, the United States provided the bulk of the artists. Other West European countries were totally ignored, as well as other parts of the world like East Europe, Africa, Latin America and Asia.

The third phase begins with the appointment of Nigerian-born Owkui Enwezor (the first non-European curator) and his global art documenta in 2002. And this will become the model ever since for today’s neo-liberal biennial that we see reproduced urbi et orbi.

M.R. - Manifesta, the touring biennial who reached its finest moment in 2000 when it emerged as the first pan-European Biennial, is not discussed in depth. Yet it is an interesting subject, especially considering its current reputation as a “Biennial for Rent.” Is there any particular reason why you chose to stay away from it?

P.B. - While Manifesta is internationally the best-known touring biennial, it was not the first. So, a small clarification about the roving biennial and its genealogy is mandatory here. When we think of roving or itinerant biennials, we automatically think of Manifesta. But Manifesta is not the oldest, although maybe it is the loudest. We now know that the I Bienal Hispano-americana was held in Madrid in 1951 and travelled to Barcelona; the II Bienal Hispano-americana was held in 1954 in Santiago de Cuba and travelled to Caracas and Santo Domingo, among others; and the III Bienal Hispano-americana was held in 1956 in Barcelona and travelled to Geneva. It prefigured Manifesta by 45 years! Then we have, according to Charles Green and Anthony Gardner, “the Biennial of Arab Art that began in Baghdad in 1974 and continued in Rabat, Morocco and to Jordan.”And just two years after Manifesta, we have the roaming and ongoing BAVIC in Central America, held for the first time in Guatemala in 1998. And there are other smaller and lesser known “walking” biennials, like Meeting Points, the Emergence Biennale and Land Art Mongolia, just to mention a few.

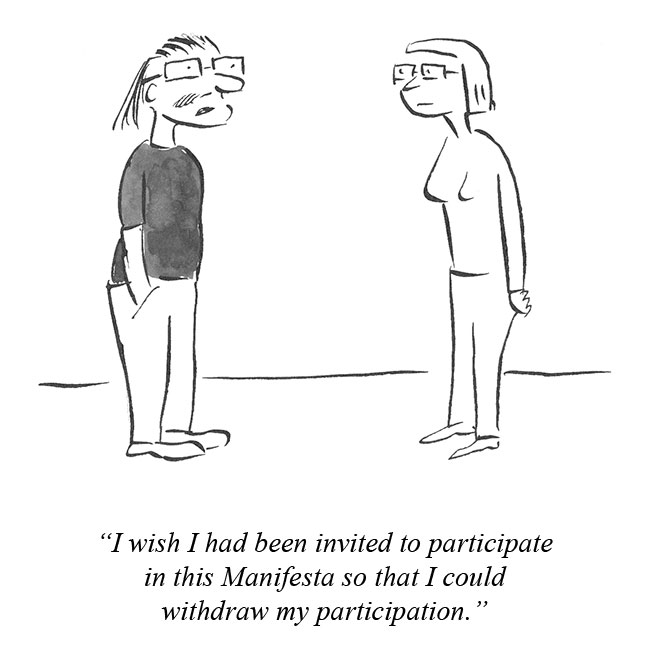

I find Manifesta or “Moneyfesta,” as Dutch critic Sandra Smallenburg finely renamed it, interesting as the perfect example of the neo-liberal biennial modeland how it changed its discourse according to the blowing of the “money wind.” First it was supposed to enhance relations between East and West, but it only happened once in Ljubljana. Then from 2010 the focus changed towards the relationship Europe-North Africa. But in hardly 20 years it will be held three times in Spain: 2004 in San Sebastian, 2010 in Murcia and in 2024 in Barcelona again! I only see, as you rightly say, a “Biennial for Rent.” The city that pays the staggering hiring price of the Manifesta brand which started, let’s recall, in Frankfurt (2002) with €1,3M and amounted to proximately €8M in Marseille (2020), will ring the bell.

Now, was or is Manifesta a relevant biennial from a conceptual or a curatorial perspective? Not really! It is most of the time focused on young emerging art, and as such more cutting-edge and chaotic, but it doesn’t add much to the curatorial discourse. From all the biennials held, I think the Manifesta 6 Nicosia School project by Mai Abu ElDahab, Anton Vidokle and Florian Waldvogel was a daring proposal but, as you well know, it wasn’t finally carried out. Maybe the engagement of Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities was too utopian, and precisely that was what made it particularly interesting. And I just haven’t found that kind of interest in most of the Manifesta editions.

M.R. - There were other reasons why Manifesta 6 didn’t work out regardless of the rocky relationship between the curatorial team and the Cyprus authorities. The curators didn’t get along to the extent that each went on to organize their own separate segment; there were budget issues; the idea of turning the exhibition into a school was debatable; and the concept of trying to reunite an island that had twice rejected this notion via referendum was arrogant-not utopian. It was a lost opportunity on many levels.

P.B. - You are far better informed than I am on the topic. I guess this is what happens when utopia meets Realpolitik! But this is precisely in my opinion the role of the biennial: not only to frame the Zeitgeistbut to propose the curator’s Weltanschauungwith all its utopian, radical, alternative or uncanny propositions, as flawed as they may be. Art’s role for me is to annoy society, to cause discomfort, to provide society with new perspectives. The Dana Schutz affaire during the Whitney Biennial (2017) with her challenging painting of Emmett Till entitled Open Casket (2016)is a perfect example of how the art world can serve as agitator or platform for triggering larger discussions that are relevant to society, in this case the Black Live Matters (BLM) movement.

M.R. - Another event you only mention in passing is Dak’art—arguably the most successful biennial on African soil. Is it because you don’t think it would contribute anything to your general narrative? Or is it simply a geographical area that doesn’t interest you as others? I’m thinking about the Latin American Biennials—São Paulo, Havana and the Bienal Hispano-americana among others-another untold story that you focused on.

P.B. - It’s difficult to keep track of all biennales. And honestly, I don’t have much information about African biennales. And I have never traveled to Africa, unlike other continents where I have been able to visit many biennials. So, that’s above my pay grade and I leave that to African scholars or those interested in Africa. Dak’art would be aligned with the Havana Biennial and with the Asia-Pacific Triennial representing what I have framed as the resistance biennial model.

It’s more logical and more natural for me to address and focus on the rich history of Latin American biennials, a continent that I not only have visited very often and maintain fluid connections with, but where I also had the chance of living and also working as Head of Visual Arts of Matucana 100 in Santiago de Chile between 2015 and 2017.

For me it’s surprising how little about Hispanic and Latin American biennials appears in Anglo-Saxon publications while this continent has, after Europe, the richest history in biennials, starting already in the 1950s and the 1960s. Think of the Hispanic American Biennial (1951) in Madrid; the São Paulo Biennale (1951); the II Hispanic American Biennial (1954) held in Cuba; the I Bienal Interamericana (1958) in Mexico City; the Bienal de Córdoba (1962) in Argentina; the Bienal de Coltejer (1968) in Medellin; I Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo (1978); La Bienal Paiz (1978) from Guatemala; La Bienal de La Habana (1984); La Bienal de Cuenca (1986) in Ecuador; the Panama Biennial (1992); the Curitiba Biennial (1993) in Brazil; the Mercosul Biennial (1996) in Porto Alegre; the touring biennial BAVIC (1998) in Central America; and a series of other biennials that have been created ever since. To my surprise, Asian biennials that came much later to the fore are more known among international audiences than Latin American biennials.

In conclusion: one of the goals of my book was to put the spotlight, on one hand, on the rich and fascinating tradition of biennials in Latin America that remains largely untold and, on the other, to counteract some of the readings done by Western scholars on the São Paulo Biennial and, especially, the Havana Biennial.

* A smaller version of this interview appeared in Universes-in-Universe on January 2021.

Notes

1. Murray Edelman, From Art to Politics: How Artistic Creations Shape Political Conceptions(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 1-5.

2. Ernst van Alphen, Art in Mind: How Contemporary Images Shape Thought (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), xiii.

3. Joseph S. Nye, Jr., “Soft Power,” Foreign Policy, No. 80 (Autumn, 1990): 153-171.

4. Vittoria Martini, “A Brief History of I Giardini,” in Muntadas. On Translation: I Giardini, exhibition catalogue Spanish Pavilion 51stVenice Biennale, Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation (12 June - 6 November 2005), 213.

Michele Robecchi is a curator and writer based in London, where he is a Commissioning Editor for Contemporary Art at Phaidon Press. Some of his recent publications include monographs on the work of Sharon Hayes, Yayoi Kusama, Adam Pendleton and Adrián Villar Rojas. He was one of the curators of the 1st and 2nd Tirana Biennale.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.