« Features

PUSH TO FLUSH / Axioms of Art Style

“Any one who wishes to become a good writer should endeavour, before he allows himself to be tempted by the more showy qualities, to be direct, simple, brief, vigorous, and lucid.” - H.W. Fowler

By Paco Barragán

Some weeks ago I met Barry Schwabsky at ‘Garrison’ in Bermondsy, a café only a block away from Delfina’s in London. While we enjoyed breakfast and caught up, we discussed art writing; I asked Barry if he wasn’t going to publish a book with his writings like Jerry Saltz had done. That was a possibility, he said. Very soon in our conversation, the idea of revising and looking back into our art writings arose, but it did not always seem so pleasurable. There are articles and essays we wrote in the past in which we expressed ideas that we don’t share anymore, or, that seen in perspective, we would love to have expressed differently.

Just like a curator becomes a curator by curating, a writer becomes a writer by writing. It’s an axiomatic truth, and art style has now more than ever taken on a purely ‘axiomatic character’: it has a dubious communicative value. It serves to intimidate and, on many occasions, to show off.

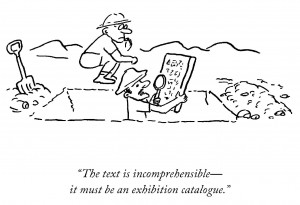

Pablo Helguera, The text is incomprehensible— it must be an exhibition catalogue. (From “Artoons,” Volume 3), 2010. Courtesy Jorge Pinto Books Inc., New York.

I remember my beginnings pretty well. Due to a lack of personal style, as happens with many young or new writers, you try hard to emulate the art style register of the ‘leading’ art critics. This means that you start to write articles, reviews, and later on catalogue texts with pages and pages that are indirect, complicated, fancy, imprecise, and pompous. This Orwellian neo-language is the price we have to pay for gaining access to the selective art club.

THE KING’S ENGLISH

A couple of days later back home in Madrid I was watching The King’s Speech, the story of King George VI-graciously performed by Colin Firth-and his quest to find his voice. This triggered immediately the association with The King’s English, a book on English usage and grammar written by the Fowler brothers-Henry Watson and Henry George-published in 1906. Both talking and writing are precisely about finding your own ‘voice.’

If you’re not a writer, I tell you that writing is tough, even for authors who don’t do anything else. The Fowlers’ maxim for a good writer was ‘to be direct, simple, brief, vigorous, and lucid,’ and to attain this principle they offered a set of practical rules:

- Prefer the familiar word to the far-fetched

- Prefer the concrete word to the abstract

- Prefer the single word to the circumlocution

- Prefer the short word to the long

- Prefer the Saxon word to the Romance

All languages logically evolve, and even if there are some imprecisions, the book is still elegant, authorative, and humorous. The classical The Elements of Style, by William Strunk, Jr., and E. B. White, also insists on this same idea of a plain English style: being clear, avoiding fancy words and awkward constructions, and writing in a way that is natural, compact, informative, and unpretentious.

Now think of the art world and art writing and you will find that it’s precisely the other way around. Art writing uses far-fectched, abstract, long, and Romance words. It uses unclear, unnatural, and pretentious style.

ARGUABLY THE MOST WIDELY USED…

Words can create a contradictory relationship with their meaning. Written originally in 1957, Barthes’ Mythologies already signals this disconnect between signifier and signified, meaning that progressive concepts became vague and void of content. Especially the use of qualifiers, in particular adjectives, is debilitating because it ‘enhances the weakening of language’ and ‘swells up the meaning of the noun.’ Thus, continuing with Barthes’ idea, the adjective has to present the noun in a ‘totally new, innocent, credible condition.’

Style is more a matter of attitude than of composition. Your ‘adjectivation’ becomes your DNA. The question is vital. Why? Writing is one way to go about thinking, sharing ideas, and, if necessary, convincing.

Now compare my adjective list, which includes what is distinguished and distinguishing:

1. challenging

2. emerging

3. thought-provoking

4. engaging

5. radical

6. provocative

7. critical

8. leading

It seems unlikely that the reader is not acquainted with these, but here are some quick examples from books at home and information received on my laptop on the same day I’m writing this article:

- [...] results in a growing cream archive of the key emerging artists… (Preface, FRESH CREAM )

- For, aside from this one glaring fault, some of the art seemed worthy of people’s attention, being radical, serious, surprising… (Julian Stallabrass’ introduction, High Art Lite)

- Under the title EAST by SOUTH WEST, curated by_vienna 2011 has invited 21 leading curators to present works by an extensive range of artists… (e-flux newsletter)

- Hello Peter, Paul Johnson has been sending me your links and I find them very thought-provoking. (Facebook message)

This stylistic ornamentation is always geared toward the future, the new, the utopia, that which is progressive and radical. But when everything is defined as emerging, challenging, engaging, and critical, these adjectives end up defining nothing at all. Be it laziness, the lack of precision, or the desire to impress, this rhetorical and dubious usage does not convince but confuses.

As a funk lover, I would suggest a couple of ‘J(ames) B(rown)’ adjectives for more groovy writing: the art of Marina Abramovic is dynamite; Jerry Saltz’s writings are as provocative as the King of Funk; and the thought-provoking ‘Marathon series’ conceived by Hans Ulrich Obrist, the Godfather of Soul… Can we hit it and quit? Yeah!