« Features

Push To Flush: Curating as Metanarrative (On the Metatextual Nature of Curating)

Too often I hear the complaint that curators, especially when conceiving a concept-based group show, merely use artists to illustrate the statement they’re trying to put forward. This accusation is not only sustained by practitioners outside our artistic realm, but its fiercest champions are to be found among the ranks of art critics, art historians and artists.

I sincerely find this an old-fashioned, unchallenging and seemingly odd assertion.

The first argument is more of a practical nature and could be on its turn addressed with the following question: How does the discourse of an exhibition come about? If we leave aside commemorative exhibitions, biennials and festivals in which the curator has to respond to a previously determined umbrella theme or concept, there are basically two distinctive tendencies in curating: the exhibition as a result of a concept the curator wants to explore as part of the way she or he understands the world’s narratives and enables the coming together of artists, works and processes under a spatio-temporal context (the curator engages primarily with artists and their existing works and doesn’t normally go around commissioning new ones to prove her/his point); and the artist’s works, processes and discourses that reveal to the curator certain aesthetic and/or theoretical speculations that contain the seeds of a curatorial experience, as it’s the artist who prefigures and configures the curator’s concept, while the artist or artwork becomes the maker of meaning.

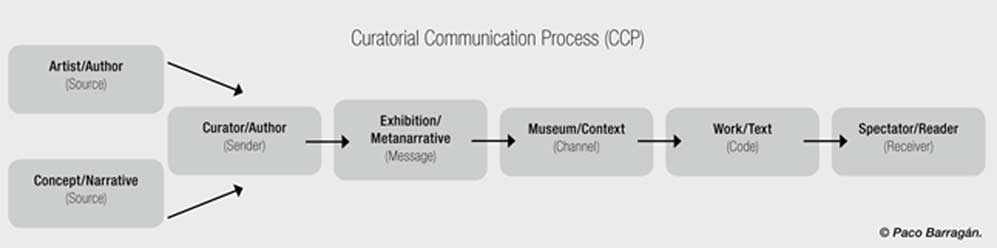

Every exhibition is a “text” considered from a semiotic point of view, a message that has been constructed in any medium and may be typographic, oral or visual in nature.

That brings us to the second argument: If an art historian, art critic, novel writer, historian et al relies for his/her research on other practitioners, theories, concepts, and credos which they profusely quote in their texts, why should this be denied to “the curatorial” and, furthermore, dispatched in this case as illustrative, inappropriate or even abusive?

Sorry, but I can’t really see a big difference between writing an article or an essay using the quotes of theorists, artists and art works and curating an exhibition not only using quotes from theorists and artists but also relying on the physical presence of artworks. Both exercises simply use examples to account for or clarify an idea that is narrative by nature.

And here is my third argument: the metanarrative nature of curating. But first we need to delve into the narrative condition of society.

Be it myths, fables, history, videos, films, video games or our daily conversations, narrative is, to quote Roland Barthes and his Structural Analyses of Narratives 1977), “under this almost infinite diversity of forms present in every age, in every place, in every society; it begins with the very history of mankind and there nowhere is nor has been a people without narrative.” At the same time, to paraphrase Jean-Luc Godard, a narrative has a beginning, middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order.

Narrative basically allows us to relate to time by selecting and ordering those events that are relevant to us and our particular perspective of the world.

In short, metanarratives, also known as les grands récits, are philosophies, theories, ideologies, discourses or ideas that provide a totalizing, authoritarian and comprehensive explanation and legitimation of the world in terms of our historical experience or knowledge. American historian Hayden White codified four Western master narratives: Greek fatalism, Christian redemptionism, bourgeois progressivism and Marxist utopianism. We could add a fifth, typically 20th-century metanarrative: totalitarianism, such as fascism, Nazism, Stalinism and Maoism.

The prefix “meta” suggests both “beyond” and “about.” Hence, a metanarrative is a big story that may contain other small stories. It is also metatextual in nature, as Gérard Genette examined in Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree (originally published in 1982): a metanarrative involves a relationship with other metanarratives without necessarily quoting or mentioning them.

And, of course, mention must be made of Jean-François Lyotard’s Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, the canonical book on postmodernism’s authoritative discourse, in which he defines postmodern as “incredulity towards metanarratives.”

Curating is metanarrative, as it embodies a narrative about narrative dealing with the nature, structure and signification of curatorial narratives. Every curator selects and orders artworks, and her or his perspective adds to the subjectivity of the narrative. And, as such, the curatorial constructs a text that refers to the generation and accumulation of meaning across texts.

We could say that an exhibition is basically a text that constructs the meaning of the past in the context of the present.

Like fiction, history and art history, an exhibition is always metanarrative: It tells a story about a story, and the curator uses, as Hayden White would argue, a mode of “emplotment.” And especially a good exhibition is the more so, as it explains the world to us (metanarratives) and let’s us explain ourselves to the world (micronarratives).

Paco Barragán is an independent curator and arts writer based in Madrid. He is curatorial advisor to the Artist Pension Trust in New York and recently curated “The End of History…and the Return of History Painting” (MMKA, The Netherlands, 2011). He is a co-editor of When a Painting Moves…Something Must Be Rotten! (2011) and the author of The Art Fair Age (2008), both published by Charta.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.