« Features

Push to Flush: Pop Culture Versus High Art (Reflections about an Undialectical Dialectics)

First capitalism took over pop culture, and now it has taken hold after years of high art. Defining culture can be very complex and contradictory (William Raymond’s definition is still valid), so I depart from an expanded notion that includes both high and low artistic expressions.

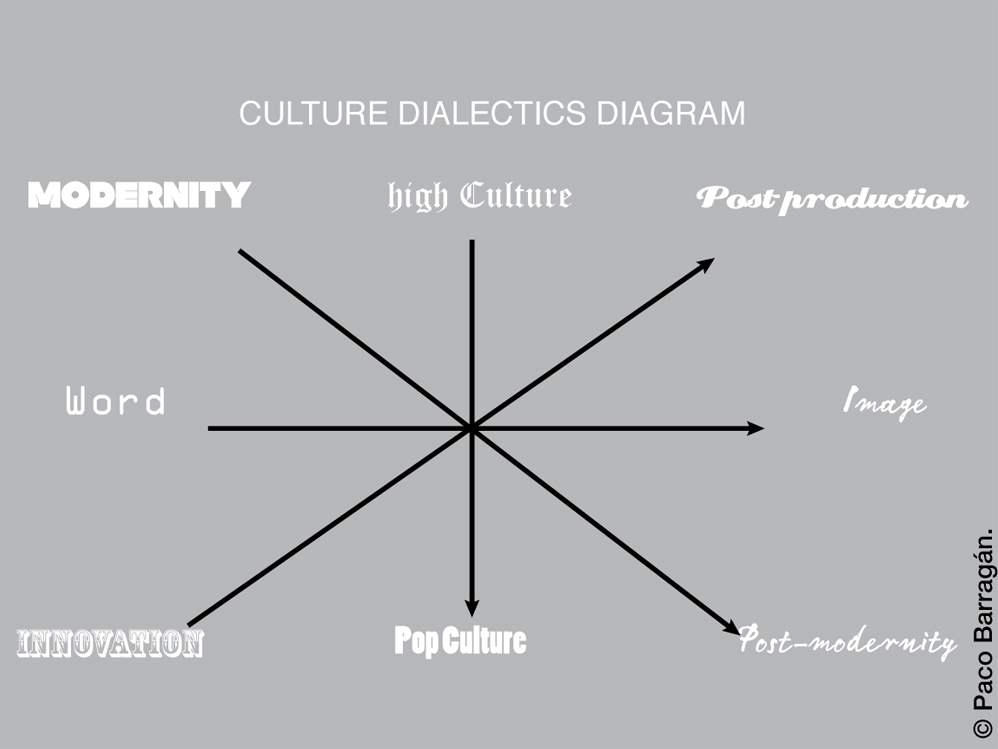

If we accept that pre-modern times were characterized by religion-faith-believing while modern times by science- reason-seeing, we could end up articulating post-modern times by culture-emotion-feeling. Sticking now to the modern-postmodern dialectics, this could be summarized by two major shifts: a progression from modernity to postmodernity determined by a) a word-based to an image-based society and b) a high art to a pop culture displacement in society, as well as c) a subsidiary shift from innovation to post-production. This enables us to sketch a simple but clarifying culture dialects diagram (CDD) as reproduced below. Of course there are many other oppositional paradigms at play-autonomy-engagement, style-neo-style, utopia-dystopia, linearity-non-linearity-but in support of my argumentation, these are the three principal markers.

FROM WORD TO IMAGE

Society has shifted from a word-based culture to an image-based culture, a shift that occurred sometime in the late 1960s. The advent of hyper-consumerism, pop culture, mass media, celebrity politics and entertainment industries signals this new paradigm that challenges the ruling class and intellectual modernism’s hegemony. Postmodernism and postmodernity are the projection of this crisis.

Scholars have affirmed this claim in a variety of ways over the past few decades: Fredric Jameson (1991) argued that media society required not merely study but the establishment of a whole new media-lexicological subdiscipline; and Zygmunt Bauman (1992) signaled the loss of intellectuals’ authority in contemporary culture and society and their ability to dictate standards of taste, truth and morality. Furthermore, Pierre Bourdieu (1984) also acknowledged the intellectual preference for print-based rather than televisual culture as a difference in class taste through which the ruling class deploys cultural capital, and among this short list I would also mention Régis Debray (1996) who described it very appropriately: The “videosphere” (mediasphere) has succeeded the “graphospere” in which print-based media was once predominant.

In short, text-based culture used to be represented by books and some paintings and sculptures that required concentration, linearity and literacy. Critical appraisal and “truth” were the result of written and verbal reasoning, of contrasting the “truth” of an information with other texts or even discussing it face-to-face. Power was based on a reasoned critique exerted by a limited reading public that debated matters of culture and politics in a public, local sphere, maintaining as such a link between social situations and a sense of place. Visual culture in turn requires a short attention span, is non-linear, global, not necessarily literate and more emotional.

FROM HIGH TO LOW

The progression from “word to image” goes hand in hand with the shift from “high to low culture”, which is totally inherent to pop culture’s ideosyncrasy.

So what exactly makes culture “low” or “popular”? Both carry distinct and at times contradictory connotations, depending on one’s aesthetic values. In the art world it is still determined by a definition from Clement Greenberg’s seminal essay Avant-Garde and Kitsch, published in 1939 in the magazine Partisan Review. The binary opposition between avant-garde and kitsch has since then branded with great violence the cursed destiny of popular culture. Greenberg was one of the first to remind us that formal culture was only destined to be available to those that were literate and enjoyed the necessary leisure time and comfort. So, basically what Greenberg does is frame popular culture as “kitsch.”

Modernity brought about a dynamics of secularization of culture, politics, family, state and jurisdiction. Gilles Lipovetsky and Jean Serroy claim in La Culture-monde (2008) that during the last 30 years we have created a “culture-world,” within which democracy has leveled all differences between high and low art guided by a market that has colonized culture and all modes of living.

Pop art and postmodernist strategies basically democratized art and made it more accessible. They stood for, to quote Hal Foster’s The First Pop Age (2011), “a signal shift in the cultural fashioning of the individual.” But in this “Second Pop Age,” pop culture is not the only movement that has absorbed cult references (think of Madonna and Lady Gaga and films such as Bladerunner), but high art has also become poppish and kitsch (Koons, Hirst, Cattelan et al), as artists have became post-producers too (Bourriaud).

For more than 50 years now, “undialectical” interpretations have focused on negative visions of contemporary culture and its commodified, indoctrinated and conformist character (see Adorno, Debord, Habermas and Rancière, among others). This not only expresses a kind of iconoclastic antipathy toward images and academia’s fierce monopoly on cultural capital, but also denies any critical potential for pop culture in regard to democratic and progressive policies, as Walter Benjamin would have argued.

The question still remains: Is art history still the place from which to develop a more critical and challenging interpretation of the dialectics of culture?

Paco Barragán is an independent curator and arts writer based in Madrid. He is curatorial advisor to the Artist Pension Trust in New York and recently curated “The End of History…and the Return of History Painting” (MMKA, The Netherlands, 2011). He is a co-editor of When a Painting Moves…Something Must Be Rotten! (2011) and the author of The Art Fair Age (2008), both published by Charta.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.