« Features

Push to Flush: The Post Syndrome

It’s always tempting to search in the archives of “post-modernity” for the authentic sense of our times. For some writers and scholars, post-modernity has gone out of fashion, for others it’s simply dead, and for a third party it’s still alive and kickin’ (as the song says).

Be it discontent or fervor, the fact is that this concurrence of symptoms (from the Greek syndromos) has brought about a series of formal attempts to define and name the epoch succeeding “post-modernity” and “post-modernism” (if we are to state a proper definition we’re obliged to frame “post-modernity” as a term referring to social, economic, political and technological developments that single out the transition from a “modern” to a “post-modern” organization of life, while “post-modernism” refers to art, architecture, literature and cultural criticism that have subverted and flattened the elitist hierarchies of modernism).

Gilles Lipovetsky suggested the term “hyper-modernity” characterized by a hyper-consumerism and a hyper-individualism as a synonym for deception, anxiety and frustration; Nicolas Bourriaud titled his Tate Britain’s fourth Triennial “Altermodern”-a new modernity based on translation in a world network and connected to the creolization of cultures and the struggle for autonomy; and Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker introduced the term “metamodernism” as an intervention that oscillates between modern and post-modern strategies characterized by “informed naivety,” “pragmatic idealism” and “moderate fanaticism.” I also participated in the debate by suggesting the term “neo-modernity” as a critical reformulation of the past and the re-reading of certain artistic movements and fields, such as neo-baroque, neo-romanticism, neo-anarchism and neo-ecumenism.

“Hyper,” “alter,” “meta,” “neo”-they all share in common “modernity.” From a historical perspective, that which is “modern” is in battle against that which immediately preceded it, and as such, “modern” is always “post-something-else.” The prefix “post” suggests the overcoming of a previous movement or situation.

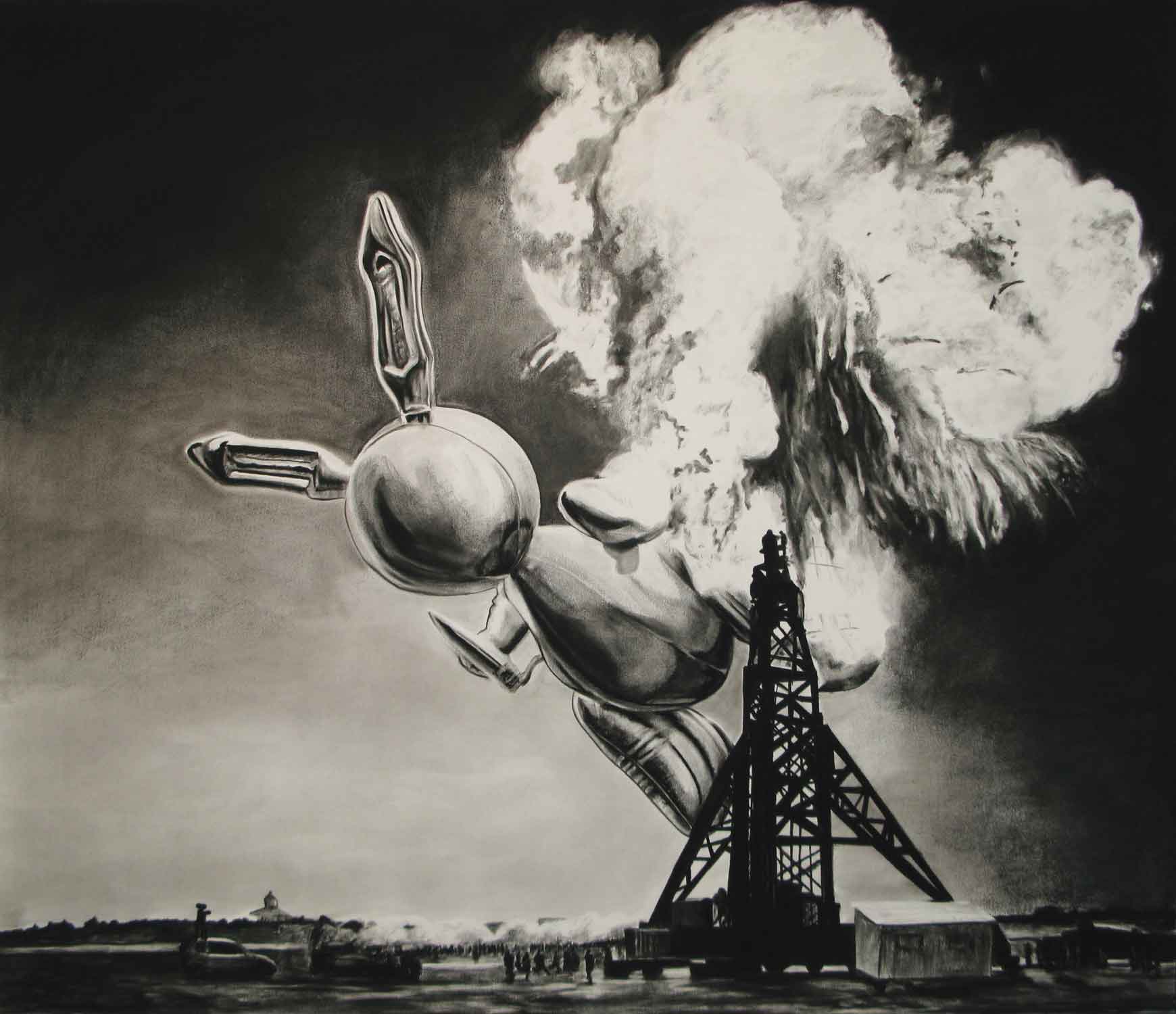

Trevor Guthrie, Hindenbunny (metaphor for 21st Century art market hype), 2008, charcoal on paper, 44”x37.4.” Courtesy Galerie Römerapotheke, Zurich.

THE AGE OF POST

I’m tempted to believe that we are stuck in the “post” syndrome.

We know from Fredric Jameson that modernism’s cultural logic in late capitalism is “post”: Art and culture have ceased to be super-structural in relation to economy revealing its relations of production and consumption (changes in the super-structure are traditionally very, very slow). We are aware from Boris Groys through his Art Power that, “The desire to get rid of any image can be realized only through a new image-the image of a critique of the image.”

And as such, for some, “post” has succeeded itself, id est, post-modernism has become “post-postmodernism” (without the second hyphen). I believe it was Sophocles who expressed in Antigone the sentiment that “no one loves the messenger who brings bad news.” But if you still want to kill someone because of this gibberish, please shoot at landscape architect and urban planner Tom Turner, who advocated for a “post-postmodernism” that seeks to “temper reason with faith.” At least he admitted to praying for a better name for it.

We all have heard that even history is “post-historical,” and all its “meta” or “grand” narratives have failed and crashed (Fukuyama, Lyotard, Baudrillard). Economy is “post-industrial,” and it’s all about accessing, manipulating and distributing information (Rifkin, Castells). Today’s predominant mode of politics is “post-politics”-a politics that claims to leave behind old ideological struggles and, instead, focus on expert management and administration (Žižek).

Since the 1990s, feminism has been challenged by the so-called “post-feminism,” rejecting the rigid gender politics of second-wave feminism and instead see gender identities as less fixed and personally empowering (Ouellette). Related to it is “post-pornography,” an artistic movement that’s not only about sexual pleasure, but also about opening up to peripheral, dissident, alternative representations of the body beyond the traditional male, patriarchal heterosexual codification (Salanova).

But let’s return to the art world. Post-Fordism translated and transferred problems, methods and practices that were thought to be specific to art to other domains: discontinuity, flexibility, mobility. Work and leisure are no longer separated, and large amounts of unpaid time are invested in accumulating knowledge for achieving future projects under these market-driven conditions.

According to Bourriaud, artistic practices have long since become a matter of “post-production”: the idea that the artist is a “post-producer” who inserts his work in that of others and abolishes “the traditional distinctions between production and consumption, creation and copy, readymade and original work.” Hal Foster for his part elaborates on the idea of “post-criticism,” questing whether there is any space for critical thinking today, and even going so far as to suggest its possible out-of-date-ness.

Finally, the art world too is aware of its contradictory status of art both as commodity and autonomous object. As a way of critiquing the existing binary opposition between “non-commercial” and “commercial,” art historian Toke Lykkeberg has suggested the concept “post-commercial”: It analyzes not only the specific problems between symbolic and market value, but between (high) art and (popular) culture and its intrinsic and problematic relationship with intellectual authority. Regardless of the fact that Hirst and Koons have been dubbed the “kings of kitsch,” they’re the perfect example of the “post-commercial” force that rules the art world.

I would even dare to say that both religion and ecology have become “post-addicted.” God or nature created the best of possible worlds, and any change can only be for the worse-or even apocalyptic.

To post or not to post-that is the question!