« Features

Revisiting History: A Conversation with Meira Marrero and José Angel Toirac

Meira Marrero (Havana, 1969) and José Angel Toirac (Guantánamo, 1966) (M&T) have been working together for a couple of decades. They rely on controversial historic material and create their works from a discourse similar to the codes of official historiography. Their works feature plenty of symbols and citations that refer to specific moments in Cuban history, but also to universal history.

By Irina Leyva-Pérez

Irina Leyva-Pérez - Collaboration between artists is not unusual, and although there are many examples in the history of art, we can say that since the 1960s it has become a relatively constant occurrence. Each has its special characteristics, and in your case you form a very specific duo, Meira with her training as an art historian and Toirac as an artist. When did you start working together? What do each of you contribute to the finished product? What is your work process?

José Angel Toirac - We started working together little by little, without even deciding to do so at the beginning of the 1990s. Our generation was prolific in collective projects and interdisciplinary works, because we tried to confront institutions and the type of art they habitually promoted. For this, the collective voice was more effective than the individual one; in the event of an official adverse reaction, the ‘blows’ would be less if there were more of us to share them.

In our specific case, ever since we met, we have always supported or confronted each other when we had an idea or when we started a creative project. Then, at a certain point along the way, we decided to accept what had happened spontaneously and we formed a work team, where the fundamental contribution of each is to be the complement of the other. The existence of this constant counterpoint is what causes ideas to develop and the creative process to advance until finally presented as a work of art. Our work method is to develop two or three ideas at the same time; they are parallel investigations, although, at times, they intersect with each other. It is at this stage that Meira plays a predominant role, and when we are invited to participate in an event or an exhibition, we present as ‘plan A’ the project we deem most appropriate for the occasion, while also having a ‘plan B’ and even a ‘plan C’ up our sleeves.

José A. Toirac and Meira Marrero, Vanidades (Vanities), 2013, oil on canvas, 45” x 32.” Photo: Fernanda Torcida

I.L.P.- You also collaborate with other artists, as in the case of the videos and more recently Vanitas Vanitatum, the sculpture you presented in “Vanitas,” your latest individual exhibition. How do you select the artists you collaborate with?

Meira Marrero - In our work process, everything is determined by the idea, and the work of art evolves as the idea develops, so that if the piece needs to develop as a painting Toirac does it, since his academic training as a painter allows it. However, when it involves photography, video or sculpture, we do not hesitate to turn to an artist who can best create the work using that art form. On more than one occasion, during the investigation, we have relied on specialized help in order to delve into a theme and save time. Such is the case with the piece Cuba 1869-2006 (2006), on which we collaborated with the historian Marilú Uralde in order to ascertain the exact dates during which Cuban heads of state unlawfully held power. Another investigation, much more complex in many ways, even for a professional investigator like Marilú Uralde, was required for the piece Vanitas (2006-2013), which lends its title to the show at Pan American Art Projects. This piece includes portraits of all the Cuban first ladies from 1902 until 1976. Putting together a presidential chronology is perhaps achievable in other countries, but it can be extremely difficult to obtain precise dates in a society, such as Cuba, where presidential history has been vilified. You can imagine how difficult it is to unearth not only the ex-presidents, but also to look for images of their first ladies, a position that no longer exists in today’s Cuban political hierarchy, having ended in 1976, when Fidel Castro assumed the Cuban presidency.

José A. Toirac and Meira Marrero, Vanitas vanitatum, 2013, marble sculpture, 17.50” x 13” x 10.” All images are courtesy of Pan American Art Projects.

Since Vanitas Vanitatum (2013) had to be sculpted in white Carrara marble, we enlisted the collaboration of the sculptor Roberto Pérez Crespo, who has vast experience with all types of stone. As you know, the Vanitas genre has frequently been addressed through painting, but our idea was to create a three-dimensional Vanitas, starting with a Vanidades magazine cover, from which we had already created a painting (Vanidades, 2013). We engraved the Latin phrase ‘Vanitas Vanitatum’ on the base of the sculpture, which translates as “vanity of vanities.” The idea of making the genre three dimensional was expanded until the entire show functions as an installation.

I.L.P.- “Vanitas” is comprised of very complex works, with various levels of interpretation and very concrete historic referents. In spite of the fact that the exhibition has a unifying thread, each piece can be analyzed based on various referents and consequently interpretations. Is it a characteristic of your work that it often favors a mistaken or partial interpretation?

M.M.- The shortest answer to your question is that mistaken or partial interpretations are the lot of works of art. After all, every work of art that is displayed is exposed, in the widest sense of the word, because many filters intervene, for good or bad, in its assimilation and enjoyment. Let us put it this way: No one can prevent a grammatical analysis of Don Quixote, but the analysis does not exhaust its meaning nor does it explain its literary transcendence. Of course, one must have a certain sensibility and cultural background to want to read that book and enjoy it as literature. In our exhibition, for example, the idea of the passage of time is the thread of Ariadne that guides the tour of the show, structured like a classical Vanitas-style painting. It is just that here the gallery walls are like an enormous laid-out canvas, showing objects apparently unrelated to each other, but which all refer to the fleeting nature of what we can acquire in life. Thus, each of the pieces that comprise the show plays an allegoric role: the chronology of the battleship Maine in the port of Havana and images of the monument erected at the Malecón (Remember the Maine, 2013) play the same role within our exhibition as the sand clocks in traditional Vanitas. Memento Mori (2013), an audio installation inspired by a story of ancient Rome, is like those musical instruments present in still life, representing music as an intense although ephemeral expression and experience. At the end of the day, glory, friendship, fortune, social status, ethical convictions, memory, beauty are things that can change in aspect, thus changing our lives.

I.L.P.- Getting back to “Vanitas,” which brings together works from various periods, we see those that could be seen as very local because of their unmistakable references to the Cuban context. Nevertheless, in spite of representing problems very specific to this country, they are at the same time universal since many could be approached from a more global philosophical point of view. I refer to pieces such as Amistad and Cara y Cruz.

M.M.- Art is like an intersection where personal and local stories converge with other regional stories and even with ‘universal history.’ When we work with an image such as Che, for example, we understand the process that converted the real figure into a mythical image. This mystifying process has encompassed other figures like Jesus Christ or a Homeric personage like Achilles, to cite just a couple of well-known cases. Furthermore, our work is part of the historicist tradition of art, and in that type of oeuvre there are always local references, because you have to place the stories somewhere. If you are trying to add some truth to the matter, what better place than one we know very well, although that does not mean that we deal with exclusively Cuban themes. Friendship, for example, is not. Developing that theme starts with a true and convincing experience. Our piece Amistad (1993-2013) is a triptych that refers to the friendship between Cuba and the former Soviet Union. It was created and shown for the first time the same year in which the Soviet Union officially announced the suspension of support for the Cuban economy. Stored for 20 years until now, the painting visibly shows the signs of physical deterioration, similar to the deterioration of the ‘eternal and unbreakable friendship’ that was extolled between the two countries. The way we touch upon the same theme in the piece Solve et Coagula (2012-2013) is different because we refer to the love/hate relationship that has always existed between Cuba and the United States.

José A. Toirac and Meira Marrero, Solve et Coagula, 2012 (detail), installation, mixed media, dimensions variable.

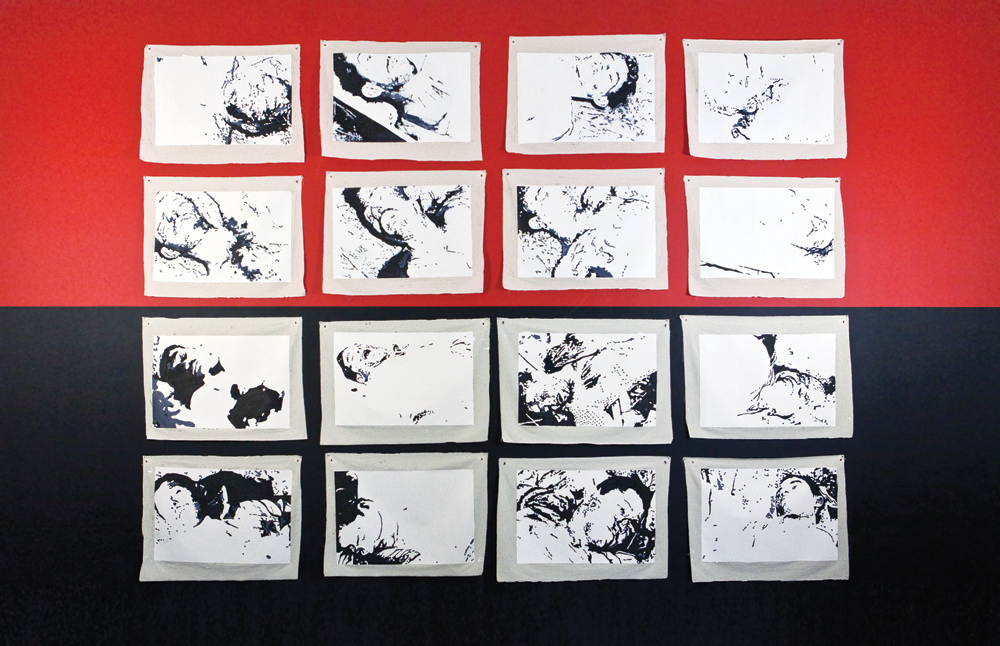

Another subject that is not endemic to Cuba is the theme of death. In Cara y Cruz (1996), we approach said theme in its purest sense. It is an installation made up of 16 portraits of deceased people, who were executed by different factions, some before the 1959 Revolution, and others after. The idea is to present the victims and victimizers next to each other, since in the end death is death, independent of the specific context. For that reason, it is impossible to iconographically distinguish ‘the good from the bad.’ From the edge of the canvas toward the middle, only the color of the wall differentiates them. Retaking the example of Don Quixote, because from a certain perspective our work is framed within the epic character that also intoxicates Don Quixote, it will always be possible to reduce the interpretation of the book to the local situation of an older, unhinged person who lived in the forgotten town of La Mancha. However, the cost of this provincial focus would be to ignore the most interesting and transcendent part of the novel.

I.L.P.- Your work has an essentially investigative component with a historic perspective. Frequently you choose historic passages that are virtually forgotten, unknown or cannot be found in ‘official’ history. For this you rely on materials in the public domain, and you create pieces from a similar discourse. This process includes ‘reproducing’ mass-media images. At other times you create objects (like the plates of Solve et Coagula) with this same aesthetic. The process of conceptualizing appears to be deconstructive in the literal sense of the word; that is to say, you deconstruct historical events in order to analyze them from a factual perspective. A work that could be considered to represent this process would be Remember the Maine. Isn’t that so?

M.M.- Yes. The Latin phrase ‘Solve et coagula’ that we use as a title of another piece, which also refers to the explosion of the battleship Maine, refers to the method recommended by alchemists to achieve enlightenment; that process of dismembering and later reordering, which allows us to know ourselves and the world we are part of. Since all of historic reconstruction is an exercise in power, the search in the past is never neutral; it is always done based on the interests of the present, which justify the current order. We follow a process of deconstruction in the sense that we invite you to stop and think about where the images come from, why they were generated, for what purpose. In the installation we see what the monument looked like before the eagle that crowned it was torn down by decree of the Revolutionary Government in 1961. However, in the image we can clearly see that not only was the eagle torn down, but as a collateral effect of said action, the architrave that served as a base for the eagle on which the word ‘Libertad’ (Freedom) was written was also torn down.

Every time you delve into facts, very interesting information is found. In preparing the chronology of the Maine, for example, we discovered an unbelievable fact: The remains of the Maine stayed in the bay of Havana for more than a decade after the end of the Spanish-American War. Another interesting fact was how they calculated the number of victims of the explosion: by subtracting the number of survivors from the total enlisted crew members, since not all of the bodies were recovered, and of the 231 recovered bodies only 65 were identified. What made us decide to entitle the work Remember the Maine and to print historic photos on commemorative plates reminiscent of souvenirs was that the American press propagated the phrase, ‘Remember the Maine,’ lest we forget the motives which led the United States to intervene in the war at the end of the 19th century. The slogan became so popular that it was not only used as a title for patriotic poems and hymns, but it was also printed on dishes, spoons, brooches, ashtrays, paperweights, matchboxes, playing cards, children’s toys and a lot of other merchandise until it became a commercial slogan used to attract consumers. Our work comments on the conversion of patriotism into just another commercial enterprise. Nowadays, this phenomenon can be clearly seen in many countries, including Cuba.

I.L.P.- Your investigative process relies on the importance of individual memory with respect to the collective. You look for facts that should be part of collective memory but which are often relegated to individual memory. How do you see this relationship reflected in your oeuvre?

M.M. - Memory in some way is the basis on which our present attitudes are legitimized, hence its importance and fragility. As a result of the way in which the mind stores information and the format in which this information is later recovered to reconstruct past events, it is not altogether impossible to implant false memories in individuals and even communities. As you mentioned, our oeuvre always works with information that is in the public domain. What often happens is that these pieces of information are seen as isolated bits of data that end up being ignored. However, when connections are established among them, as if through magic, everything makes sense.

I.L.P. - An aspect that you have dealt with on various occasions is the commercialization of history. In ‘Vanitas,’ you do it with Remember the Maine, but it is something that you have addressed on various occasions with the figure of Che Guevara. The earliest example that I recollect is Una imagen recorre el mundo, a piece from 1989, in which you reproduced the 1967 poster with the photograph of Guevara taken by Alberto Korda. Why are you interested in this almost fetishistic phenomenon?

J.A.T.- The theme of commercialization is a theme that we have systematically addressed over the years, perhaps in order to be at peace with ourselves. Remember that we were educated in the belief that transiting through the market was the worst possible destination for a work of art and that the most abhorrent offense would be to accuse an artist of being commercial. So, you can imagine what a surprise it was to discover the great international impact of the Che Guevara photo. It was due to an aggressive marketing mechanism established by Editorial Feltrinelli after the death of Guevara in Bolivia. I believe that in the end, we have had to exorcise ourselves of this simplistic view of commerce and to understand the market as one of the natural and necessary components of the artistic ‘ecosystem.’

I.L.P.- In recent years your work has been included in two exhibitions about social activism; I refer to ‘Queloides’ and ‘Subrosa.’ Do you think that your oeuvre can be considered social activism?

M.M.- Well, if it is assumed that art does not have the power to change social reality immediately, but that it can change the way we perceive reality, then we can say that our work is socially activist in the long term.

José A. Toirac and Meira Marrero, Cara y Cruz (Heads and Tails), 1996, installation (16 paintings), oil on canvas, each: 31.5” x 47.2”. Photo: Magnus Sigurdarson.

I.L.P.- Toirac, you are one of those artists who uses different materials to paint; not only traditional oils, but you have used others such as wine and soda. But when you paint with oils, from very early on in many of your paintings, we can see a very specific palette that contains gray, black and white tones. Does this selection carry any particular symbolism?

J.A.T.- The use of color in our work always has a reason for being and is directly related to the material that we use as a reference for our work. Of course, when we select a photo to paint it is because of its suitability for our idea, even from a chromatic standpoint. It is no coincidence that a piece such as Amistad is painted brightly. Remember that the invention of color photography was the result of chemicals discovered after the invention of black-and-white photography. Therefore, color photographic images are more distant to reality than those in black and white. They are a kind of second-grade abstraction and thus doubly false with respect to what they represent.

Usually, we use black and white to accentuate a Manichaean way of representing the world that demands that we take a position with respect to what the image is describing in ‘black and white.’ Among other things, maturing is learning to see the nuances between two poles. For a time we were working on the idea of gray as an indeterminate point between the two extremes. We created a series of paintings that we entitled Gris that were halfway between black and white, between realism and abstraction, although they came from very well-known black-and-white photos. We have changed the color of the referent in very few cases, as in La Ruleta, in which we used red to paint a black-and-white photograph of a gaming table at the Hotel Nacional taken by Constantino Arias in the 1950s. Our idea of translating the original black-and-white photograph into oils in the color red was to emphasize an idea already implicit in the roulette wheel: that today is black, tomorrow can be red, or vice versa.

José A. Toirac and Meira Marrero, Solve et Coagula, 2012-2013, installation, dimensions variable. Printing on ceramics by fotoceramicacuba. Photo: Fernanda Torcida.

I.L.P.- Toirac, you are a figurative painter. I imagine that you have been influenced by artists from many periods, because one is always inspired by the great masters. One of the most direct formal influences insofar as pictorial language is concerned is Gerhard Richter. Do you think his influence extends to the conceptual as well?

J.A.T.- In a piece of ours like Cuba 1869-2006, for example, the fact that it is made up of a collection of men’s portraits, painted in black and white in a photorealistic manner, establishes an immediate visual connection with Richter’s 48 Portraits (1971-1972), even if there are essential differences in the reasons why Richter selected his images and why we selected ours. In order to understand the most profound influences on our work, you must refer to another German artist, Hans Haacke. In the same way that in his piece, Manet-PROJEKT ‘74, Haacke creates a meticulous list of all of the owners of a Manet painting, we chose and chronologically ordered the portraits of all of the Cuban heads of state since 1869, even the nail on the wall that succeeds the current president. Yes, our work is full of influences, homages and citations to other works and authors.

I.L.P.- Finally, there has been much discussion about whether painting is a genre in decline, a genre that is repeating and recycling codes and strategies of the past, which does not manage to reinvent itself, to make significant contributions in accordance with today’s new visuality, a visuality very influenced by technology, the digital, the Internet, etc. Nevertheless, there is another equally established point of view that says the exact opposite. Do you think that contemporary art is more a question of content than technique? Toirac, what is your experience as an artist?

J.A.T.- Science has demonstrated that our vision is not limited to just the eye; rather, it expands to the mind. In such dizzying times, it is important to stop and study the way in which current visuality is being shaped, the way in which hegemonic notions of the true, of the real are being formed. Long ago, Leonardo da Vinci defined painting as a mental practice, and this has been shown abundantly in contemporary art’s versatility and capacity to adapt and survive.

Irina Leyva-Pérez is an art historian, art critic and curator based in Miami. She has lectured at Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts and was assistant curator at the National Gallery of Jamaica. She is currently the curator of Pan American Art Projects, a regular contributor to numerous publications and author of catalogues of such Latin American artists as León Ferrari, Luis Cruz Azaceta and Carlos Estévez.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.