« Reviews

Roberto Diago: Between the Lines

Magnan Metz Gallery - New York

Looking Through Closed Eyes

By Abelardo Mena Chicuri

A ghost runs through Cuban art: It is the spirit of abstract painting. Abstractionism, which was condemned in the 1950s by Juan Marinello in his book Conversación con nuestros pintores abstractos (Universidad de Oriente, 1960), was rejected as escapist under the directives of the dogmatic and homophobic era of cultural politics in the 1970s. During the 1980s, abstract painting was considered commercial and accused of being separate from the profound immersion in political and social actualities that characterized that decade, which is known as the Cuban Renaissance. It has now made a nostalgic return to the island, being placed in retrospective exhibitions in the halls of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes and included in the Havana Biennial, an event historically unfriendly to more traditional art.

Within the different means of expressing the abstract, Cuban artists have mainly been inclined toward Abstract Expressionism or Action Painting, which has had solid precedents in Cuba in the work of creators such as Raúl Martínez (1927-1995), Guido Llinás and the Grupo Los Once, and Antonio Vidal, to mention some of its greater exponents. The tendency toward this branch of abstraction is truly curious, because the history of Cuban art also includes a strong presence of Neo-Concrete abstractionism generated in the 1950s concurrent with Latin American Concretism.

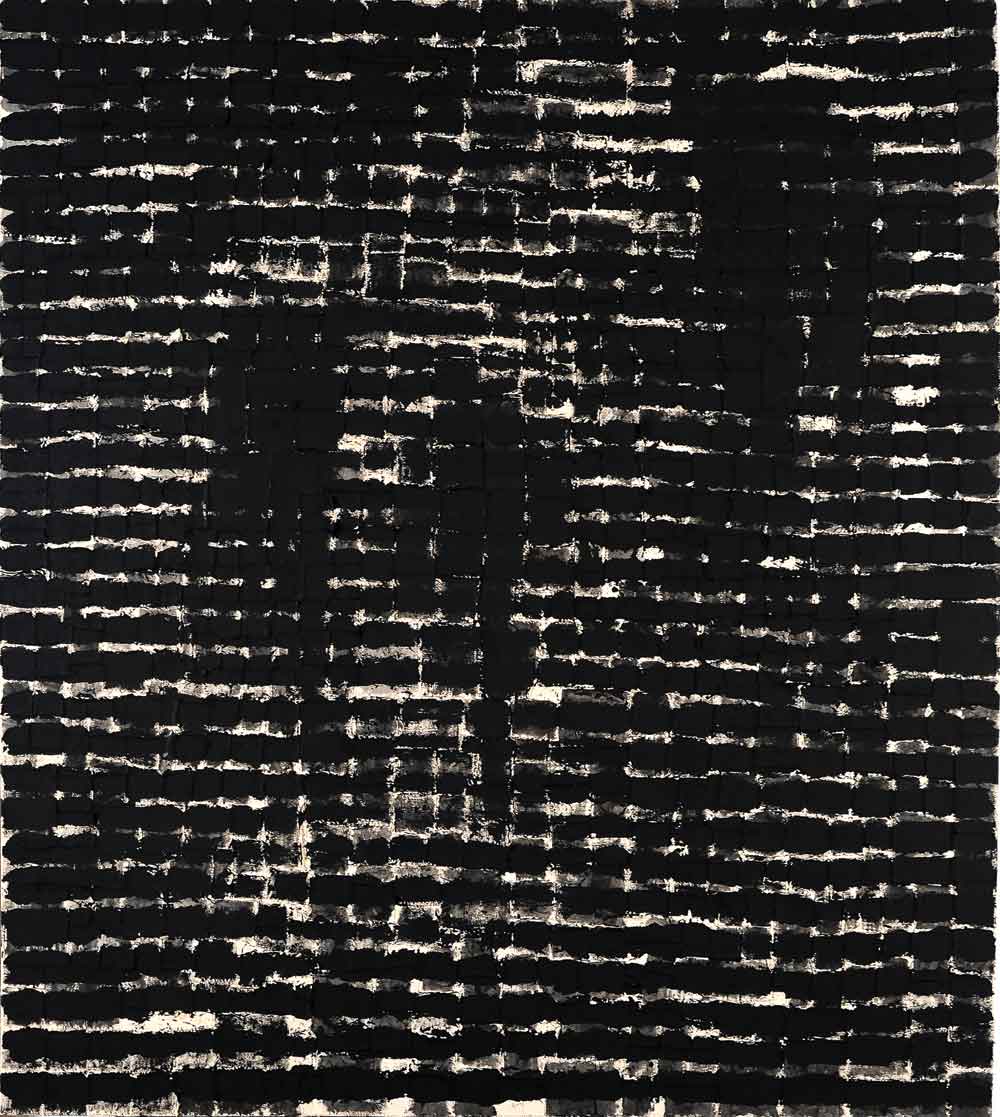

Juan Roberto Diago Durruthy, No. 7 (from Entre Lineas series), 2012, mixed media on canvas, 67” x 59”. Courtesy of Magnan Metz Gallery.

This tendency was able to generate its own galleries (Forma, Luz y Color) and left its imprint on urban interventions (Sandú Darié). Today it has achieved recognition in the art market (see the resurgence of Loló Soldevilla in Havana and Miami) and recaptured its living artists (Salvador Corratgé). The truth is that abstractionism is practiced by creators who until recently executed rural landscapes, figurative painters with academic roots or conceptualists in search of new challenges. Distanced from all orthodox militancy, it has become an exercise in creativity.

For this reason, the fact that an artist such as Juan Roberto Diago Durruthy, who is usually associated with the production of canvases and assemblages with a sociological focus, exhibits abstract post-conceptualist paintings in the space of Magnan Metz in Chelsea does not appear surprising or contradictory. Diago develops non-exclusive parallel poetics through simultaneous series that are created through different expressive methods in an exhaustive search for profound and polymorphous creativity. It is surprising, nevertheless, that for his first exhibition in New York, the gallery selected precisely this facet of his creation and did not conceive of revisiting the usual codes of his objects and canvases, characterized by allusions to institutionalized racism, the recycling of material “povera” taken from daily life and the integration of photographic portraits in crudely made tableaux, which have been exhibited in American museums in shows like “Queloides” and the excellent show of contemporary Afro-Cuban art organized in South Africa by Orlando Hernández. Confronting the sociological view of Diago would have allowed the public in the Big Apple to detect his distinctive features vis-à-vis his kindred American artists: Kara Walker, Kerry Kearns Marshall and Betye Saar, among others.

Diago’s relationship to abstractionism is not recent. The Juan Francisco Elso Contemporary Art Award was given to him in 1995 for an abstract painting and, beyond his sociological works, abstraction beats in the formal disposition of the elements utilized. For “Entre Líneas” (Between the Lines), he has omitted all figurative references in favor of the absolute hegemony of textures, colors and minimalist collage.

According to the artist, these abstract techniques refer to the symbolism utilized for the essential expression of the “orishas,” or saints of Afro-Cuban religions, deeply rooted in today’s Cuban idiosyncrasies. By dismissing the iconographic approximations with which other artists in the field (Mendive, Zúñiga) have represented the Afro-Cuban gods, Diago tries to avoid the folkloric consumption of same. The titles of the canvases, Desde el Horizonte, La Fuerza de tu ser, Entrelíneas, Paz en mi cabeza (From the Horizon, the Force of Your Being, Between the Lines, Peace in My Mind), enunciate in a confessional tone the personal truths that converse-through a private, intimate dialogue-with the reality of the color, the course material or the juxtaposition of pieces of cloth. Building bridges to the “rupturist” practices of Kandinsky, “Entre Líneas” proposes abstraction as a language capable of expressing hidden truths, like a bridge communicating with the spiritual notions of a nation.

(September 6 - October 13, 2012)

Abelardo Mena Chicuri is an art historian, curator and critic residing in Havana. He is curator of the international art collection of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Cuba and The Farber Collection of contemporary Cuban art, as well as the editor of cubanartnews.org

Filed Under: Reviews

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.