« Reviews

Alexandre Arrechea: No Limits

Park Avenue - New York

By Stephen Knudsen

Alexandre Arrechea’s No Limits1 is so good that I am going to skip the dance drill and stake out a conclusion right from the beginning. The 10 sculptures are unpardonably smart, humorous and beautiful-with Kantian flourishes of spirit.2

With art history’s grand narrative annulled (thanks, Arthur Danto), one might think art criticism’s wars of spirited yore are over.3 So, what to do with Arrechea’s genius? He deserves more than the usual narration. So here goes…writing theory with my left hand and dirty judgment with my right.4

Arrechea’s latest body of work is a sociopolitical and formal meditation on NYC icons, such as the Chrysler Building, U.S. Courthouse and Empire State Building, in a series of approximately 20-foot-tall, stainless-steel sculptures temporarily on display across a 20-block stretch of green-zone median on Park Avenue. The sculptures stand near the buildings of inspiration, making the dialogue lucid.

One point of clarification: These sculptures are not bromides; they are not mini-me replicas of the buildings they sit adjacent to. Arrechea is clearly not a cliché meister. The art works extrapolate so far out of their inspirations and into animated distortions that at a peripheral first glance one might not even see the building in the form. Some of the works shift perceptually more than others and are better for it.

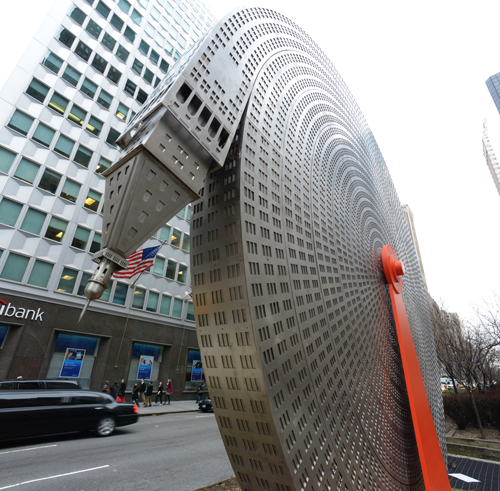

Alexandre Arrechea, Helmsley, 2013, steel, 177” x 173 ¾” x 31 ½”, located at 65th Street, Park Avenue as part of No Limits, a project presented by Magnan Metz Gallery, in partnership with the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation and the Fund for the Park Avenue Sculpture Committee.

Case in point: the Helmsley Building sculpture. This 15-foot sculpture pays homage to the 35-story building but is equally recognizable as a snake eating its own tail. The Cuban artist has spoken of the Ouroboros myth: “It’s like a city that devours itself. That has always been my first vision of New York.”5 Interesting, but even without this verbal dressing one does not need to be a herpetologist to see it. The viaduct slot at the bottom of the building, as a mouth, elegantly fellates the pretty cupola atop the building and in doing so makes perfection, a circle.

For those who like their meditations on beauty and art to be disinterested, skip this next paragraph. But I only had more respect for the work when I remembered that Ayn Rand’s famous novel Atlas Shrugged used the Helmsley building to lay bare immoralities in a backdrop of business, sex, steel, glass and concrete. The real 1929 Helmsley building is portrayed as the Taggart Transcontinental Railroad Building and office of the novel’s protagonist, Dagny Taggart. She (Dagny) is in charge of operations for Taggart Transcontinental, under her brother, James Taggart. However, Dagny is ultimately responsible for the running of the railroad, as her brother’s ineptitude and depravity does nothing but cannibalize the Taggart legacy and fortune. He does it in part by using a false altruism to debase his fellow men and women.

But to prove again that real life is better than fiction, we should remember two words: Leona Helmsley. The billionaire, the so-called queen of mean, could cannibalize with the best of them. At Helmsley’s income tax evasion trial, her housekeeper reportedly repeated the Helmsley’s mantra, “We don’t pay taxes. Only the little people pay taxes.”

When General Tire & Rubber Company sold the building to Helmsley-Spear, Leona Helmsley renamed the building The Helmsley Building and put in a clause that when sold it could never be renamed. The head just keeps eating the tail on this one.

But the work implicates us all-the circle, the wheel, the speed. In Arrechea’s sculpture, the Beaux-Arts style of The Helmsley Building spins into a wheel of Italian futurism-a mash-up true to our times. We are getting somewhere fast. But where? Do we believe in it? Is it worth it? The sculpture animates the space and speaks to it in splendid site-specific form. The sculpture is to the actual building as the animating soul is to the body. Here is hoping it is not simply a heart of darkness. Arrechea’s humor in the work lends itself to some optimism. And with that another perceptional shift is present, one concerning content: utopia versus dystopia. The brilliance in this work just keeps unraveling.

Alexandre Arrechea, Seagram, 2013, steel, 236 1/4 x 113 x 40 1/2 inches, located at 55th Street, Park Avenue.

Other Arrechea sculptures (especially the Seagram’s Building homage) have the inflated cuteness of an Oldenburg sculpture. Think of the building-to-sculpture playfulness of something like Claes Oldenburg’s and Coojse van Bruggen’s work, Shuttlecocks, at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, where the giant birdies are in dialogue with the museum building as the museum itself becomes the net.

It would have undone the piece if Arrechea’s sculpture was just cute. An added carnal playfulness comes by virtue of the red coiler against the complementary bit of fertile green bush cover. The building seeks erection as a hose-gone-wild with liquid pressure. Thus, the work is a meditation on the mid-20th-century bravado that colored the legacy of this skyscraper. Completed in 1958, it is 38 stories of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe architectural genius-and the birth of the International Style. One also thinks of the testosterone of Philip Johnson (designer of the interior) and the Mark Rothko fiasco with the structure’s restaurant, The Four Seasons. It was built for the Seagram’s liquor/beverage empire. The pressure in the hose-so to speak-was brought along by Phyllis Lambert, daughter of Seagram’s CEO. She was instrumental in the realization of the building.

Alexandre Arrechea, Metropolitan Life Insurance, 2013, stainless steel, steel, 13 1/8 x 12 1/2 x 2 1/4 ft. Located at East 57th Street on the Park Avenue Malls.

I will suggest that the most ingenious work in the series is made after the Metropolitan Life Insurance building (occupied from 1909 to 2005 by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company). The essence of Arrechea’s sculpture is so clear that a postmortem is not needed. Let me simply remark that if you stand in just the right spot, this fully coiled, hulking giant (at the ready) points down directly at you. It is an implication of life and death and the business that tempers such certainties.

In his Fifteen Theses on Contemporary Art, French philosopher Alain Badiou states, “Art…should hang together as solidly as a mathematical demonstration, be as surprising as a nighttime ambush, and be as elevated as a star.” Those words start to mean something with demonstrations like No Limits. Arrechea’s aesthetic equation perfectly positions modernity’s persistence in Postmodernism. In spite of all of the anxiety, we still want to believe in the possibility of “no limits.”6

The great irony of Arrechea’s No Limits is that despite being a temporary project, it was executed more like a permanent installation. I am left wishing this install could be permanent. The works are for sale and will have life elsewhere, but unfortunately they are so site specific that the full nature of the works is not likely to be realized again. But then again, there was that little change of heart with the Eiffel Tower. Please consider this review as the first signature on a petition to urge the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation to keep at least one of these Arrechea’s in place permanently.

(February 28 - June 9, 2013)

Notes

1. Alexandre Arrechea’s No Limits is on view at Park Avenue, from 53rd to 67th streets in New York City.

2. Arthur Danto essay “Kant and a Work of ART” 2008, from the anthology, The Art of Critique/Re-Imagining Art Criticism and the Art School Critique, c. and e. Stephen Knudsen (publishing date pending). In this essay, Danto is enthusiastic about the contemporary relevance of a kind of Kantian spirit or genius in creation of art that-unlike Kant’s ideas on disinterested judgments of beauty-spirit does embrace content. Danto states, “What impresses me is that Kant’s highly compressed discussion of spirit is capable of addressing the logic of artworks invariantly as to time, place, and culture, and of explaining why formalism is so impoverished a philosophy of art. The irony is that Kant’s Critique of Judgment is so often cited as the foundational text for formalistic analysis.”

3. On February 7, 2007 Frieze Talk Thierry de Duve speaks of his longing for “the esthetic wars of yore” and the possibility, today, of finding “the singularity of a true work of art” even as the art world loses part of itself in the reign of “exacerbated idiosyncrasies.”

< http://friezefoundation.org/talks/detail/theory_practice_thierry_de_duve/>

4. The idea of ambidextrous art criticism comes from James Elkin’s remark about Arthur Danto’s writing in Elkin’s introduction of The Art of Critique/Re-Imagining Art Criticism and the Art School Critique, c. and e. Stephen Knudsen (publishing date pending).

5. Alexandre Arrechea, Knudsen interview with the artist. This quotation was verified as accurate directly with the artist.

6. Alexandre Arrechea’s work is, for a lack of a better term, a demonstration of metamodernism, the to-and-fro occupation of both the positions of modern attachment and postmodern detachment. See Vermeulen, Timotheus, and Robin van den Akker. “Notes on Metamodernism,” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture, Vol. 2, 2010. Also see the issue No. 14 of ARTPULSE (Winter 2013) and the essay “Beyond Postmodernism.”

Stephen Knudsen is an artist and a professor of painting at Savannah College of Art and Design. He is a senior editor and art critic for ARTPULSE and a contributing writer for New York Arts Magazine, Hyperallergic, The SECAC Review Journal and theartstory.org. He is the senior editor of the anthology The ART Of Critique, which will be published this year.

Filed Under: Reviews

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.