« Reviews

Separation Anxiety

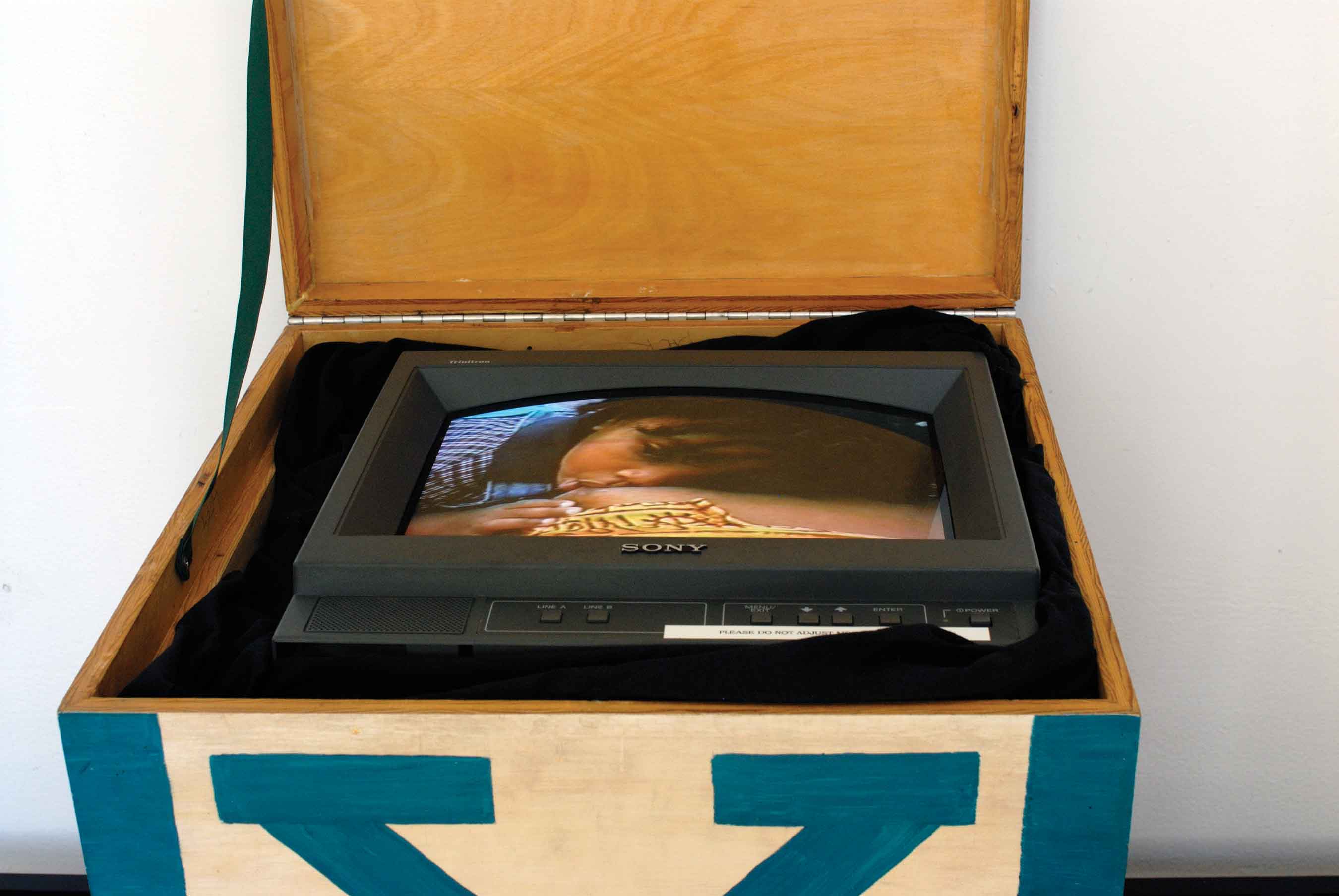

M.A.M.A. California Civil Code 43.3, 1998, wood, monitor, video and sound, 20” x 20” x 20.” Photo by Jan Volz, 2010. Courtesy Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art.

Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art - Rancho Cucamonga, CA

Curated by Denise Johnson and Rebecca Trawick

By Micol Hebron

As most women know, few things will invite a quicker escort out of the art world than having a baby. Despite the high numbers of artists with children, parenthood remains highly stigmatized in the contemporary art world. You can’t make art and be a mother (being a father is more acceptable, but still rarely discussed). When an artist announces she is pregnant, her shows get postponed, galleries remove her from their roster, and patrons talk in hushed tones about the unfortunate loss of potential, as if pregnancy were a shameful disease.

One of the most life-changing states of being, parenthood affects everything–one’s relationship to their own body and identity, the understanding of love, survival instincts, the balancing of work, art, and family, and much more. It is therefore confounding that discussions of parenthood remain so taboo in the art world. Co-curated by Denise Johnson and Rebecca Trawick, “Separation Anxiety,” at the Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art in Rancho Cucamonga, California, dares to open the conversation, with multidisciplinary work by 16 contemporary artists who examine various facets of parenthood.

The exhibition is introduced with the video California Civil Code 43.3 (1998) by the collective M.A.M.A (Athena Kanaris, Lisa Mann, Lisa Schoyer, and Karen Schwenkmeyer). Titled after the law that permits breastfeeding in public, the video is a montage of women breastfeeding, as seen from the mother’s point of view. A narrative voiceover presents numerous women describing experiences of breastfeeding and the changes in her sense of her body that are invoked as a result. The dialogue of the video raises complicated and candid observations about the body as object of desire - a simultaneous source of sexuality and nourishment.

From the image of the child’s suckling mouth, it is interesting to move to Monica Bock’s Cheek by Jowl (2008), twelve haunting silver and gold casts of her daughter’s teeth. Overtly Freudian, each set of teeth bears the holes where baby teeth have fallen out. A record of genetics and identity, the dental casts also immortalize the child’s body while it is in a state of rapid transition, alluding to the nostalgic desire to sustain and covet childhood.

Conversely, it can also be problematic when children are rushed too quickly into adulthood. Mark Stockton’s meticulous drawing Jon Benet (2009) shows misapplied projection of adult notions of beauty and femininity as the pageant star’s overly coiffed body is positioned at the bottom of the pictorial plane. She is vulnerable and dwarfed by the large empty space of the paper above her.

Given up for adoption as a youth, Marcos Rosales uses imagery and text to explore the impact of too little attention, or abandonment, upon the child. In Eau de Toilette (1995), Rosales presents fictional stories of foster home children, often mentally disabled, who exhibit disturbing, deviant, and sometimes comical behaviors that are often the result of sublimated anxiety from early interactions with the now absent parents.

The other works in the show continue to probe the intricacies of parenthood and childhood that are often too uncomfortable to articulate. Ellina Kevorkian and Haley Hasler examine the expectations and responsibilities of the mother, while Rebecca Edwards’ work is about expectations of the child. Claudia Alvarez explores the child as victim or perpetrator of violence and Kate Kretz is concerned with the child’s delicate vulnerability. Jennifer Wroblewski and Leslie Dick each collaborate with their child; Abbey Williams addresses the taboo of the artist-mother; Connie Hatch and Carol Flax’s projects are about time and lifecycles; Erika de Vries and Elizabeth Douglas’s photos show what the mother sees.

In many cases there is a palpable sense of loss portrayed in the works in the show-loss of time, of youth, of independence, of sense of self, of previous lifestyle. However, through these works of separation and loss, the viewer gains an enriched understanding of the polemics of parenthood from an artist’s perspective.

(October 11 - November 13, 2010)

Micol Hebron is the senior curator of exhibitions at Salt Lake Art Center. She is a contributing writer for Art Forum, Flash Art International and Arte Contexto.

Filed Under: Reviews