« Features

Tales of Motherhood

By Jennie Klein

Feminist artists have not always been interested in motherhood. Helen Million Ruby, one of the founding members of the activist group Mother Art and a student at the Feminist Studio Workshop in the Los Angeles Woman’s Building, was told by Judy Chicago that she couldn’t be a mother and an artist-the two were mutually exclusive.1 Chicago’s attitude towards mothers and art making was prevalent during the 1970s and 1980s; most women artists who were also mothers actively hid that fact, afraid that it would harm their careers.

It would be an over-exaggeration to claim that the topic of motherhood is suddenly a trendy issue in the contemporary art world. However, the renewed interest in feminist art coupled with the mainstream institutionalization of feminist art and artists has resulted in an increased visibility and acknowledgement of feminist art that engages with the topics of maternity and motherhood. Several books on motherhood and art have been published in the past five years.2 This past spring, Natalie Loveless curated “New Maternalisms” for FADO in Toronto. Previous exhibitions dealing with motherhood, including “Maternal Metaphors” (2004) and “Breaking in Two” (2012), have been composed primarily of objects such as painting and sculpture with some video included. “New Maternalisms,” composed of performance, video and a durational Skype performance, was much more conceptual and performative in nature, suggesting a shift in the representation of motherhood. The international roster included: Lenka Clayton (Belgium), Alice De Visscher (Belgium), Masha Godovannaya (Russia), Beth Hall and Mark Cooley (USA), Alejandra Herrera Silva (Chile/USA), Lovisa Johansson (Sweden), Hélène Matte (Québec), Gina Miller (Vancouver), Jill Miller (USA), Dillon Paul and Lindsey Wolkowicz (USA), Marlène Renaud-B (Montréal), Victoria Singh (New Zealand) and Christine Pountney (Toronto).

Like their counterparts in the 1970s, the artists included in “New Maternalisms” are concerned with the invisibility of mothers and the labor of caregiving. Many of the performances dealt with the drudgery and minuteness of daily care, such as Masha Godovannaya’s Hunger (2012), a split-screen video that contrasts the joy of nurturing a child through breastfeeding with the everyday messiness of being a mother, or Victoria Singh’s SON/Art: Kurtis the 7 Chakra Boy, a re-performance of Linda Montano’s 7 Years of Living Art. These younger artists, many of them born after 1970 and raised in a post-colonial, transnational society, are motivated by the desire to articulate a new economy of collective caregiving and mutual exchange, one based upon the values associated with motherhood. Jill Miller’s The Milk Truck (2011) is a converted ice cream truck with a giant boob and flashing emergency nipples that the artist uses to host spontaneous breastfeeding parties at institutional spaces where women have been told to stop breastfeeding in public. The work in the exhibition also reflects the changing structure of the family-several artists, such as Dillon Paul and Lindsey Wolkowicz, are in same-sex relationships and have conceived or are trying to conceive their child through ART (assisted reproductive technology). In “New Maternalisms,” process and performance replace finished objects, exposing the fissures and cracks between the ideological representation of motherhood and the lived experience of being a mother.

Young artists working on motherhood are thus interested in the body-based work of the 1970s and the conceptual work of the 1980s and 1990s. Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973-1979), a chronicle of the first six years of her son Kelly’s life experienced through the adherence to Lacanian theory, is often cited by these artists as a work of great importance. Post-Partum Document ended when Kelly learned to write his name-having entered fully into the symbolic register of representation, the piece, which was about the period of time between birth and the child’s separation from the mother, was over. Artist Courtney Kessel’s work deliberately takes up at the place where Kelly’s work ended through a performative engagement with her daughter Chloe, whose ability to engage with symbolic language is part of the piece. Kessel’s 2011 ongoing performance In Balance With makes literal these negotiations that permit her to do her work. For this piece, Kessel has constructed a very long teeter-totter with a seat at one end. The performance consists of placing Chloe in the seat and then giving her work to accomplish-such as practicing her violin, writing in her journal, complimenting her and making possible their daily negotiations. Kessel might offer Chloe something to eat, or Chloe sometimes requests something from an audience member, such as a pen to write in her journal. Each time an object is added, Kessel sits on the other side of the teeter-totter until her weight is in balance with Chloe and all of the “stuff” that comprises their life together. Interestingly, the performance ends not when Kessel has achieved balance, but when Chloe decides that the performance is finished.

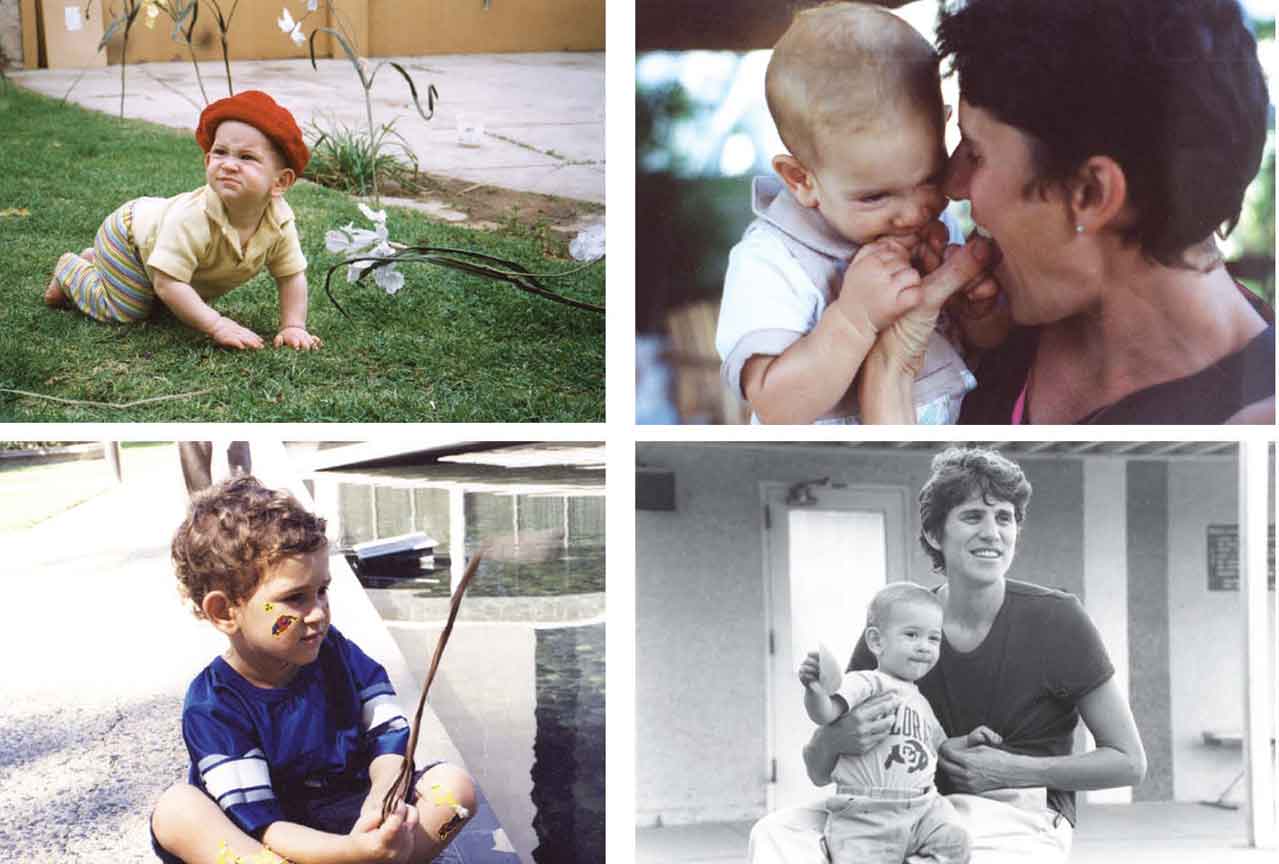

Dear Gabe: A Video-Letter from Alexandra Juhasz, 2003, 50:05, mini-dv. Director, producer and writer: Alexandra Juhasz, editor: Enid Baxter Blader, post-production: Dave Estis, score: Sheri Ozeki.

Kessel’s performance is an example of feminist mothering, defined by Andrea O’Reilly as “an oppositional discourse of motherhood, one that is constructed as a negation of patriarchal motherhood” (O’Reilly 796). Another powerful example of feminist mothering is Alexandra Juhasz’s Dear Gabe, a video letter from the filmmaker to her son.3 Gabe was conceived while Juhasz was married to the African-American filmmaker Cheryl Dunye, herself the mother of a daughter named Simone. Both Gabe and Simone, preschoolers at the time the video was made, are addressed in this video letter, which serves to show Gabe his extended family, none of whom are related to him (other than Simone, who has the same biological father). Dear Gabe traces a network of queer kinship that is assembled from various ties and friendships, all of them forged in feminism. An edited compilation of interviews with Juhasz’s five closest female friends, all of whom lived in a feminist house during college, Dear Gabe is Juhasz’s attempt to undo patriarchal mothering with feminist mothering, one that denaturalizes kinship while positing that kinship ties based on community and affinities are stronger than biological ties. Ghosting the video is Juhasz’s first great love-her friend Jim, an openly gay man who died in the AIDS epidemic. Unable to contribute his voice, Jim’s presence is acknowledged with footage shot while he was still alive, as well as Juhasz’s voice-over descriptions.

In regards to structures of kinship, Judith Butler has asked “Must the story that the child tells about his or her origin, a story that will no doubt be subject to many retellings, conform to a single story about how the human comes into being? Or will we find the human emerging through narrative structures that are not reducible to one story, the story of a capitalized Culture itself?”(Butler 128). Dear Gabe proposes just such a radical idea of kinship, one that permits the humanness of those considered not humans-”the millennial queers who must decide to make their progeny,” in Juhasz’s words-to be considered human. In fact, the implications of what anti-patriarchal maternal thought and actions might be are staggering. As Sara Ruddick has suggested, the mother develops an “attitude governed by the priority of keeping over acquiring, of conserving the fragile, of maintaining whatever is at hand” (Ruddick 99). Anti-patriarchal maternal thinking finds the human in all of us-queer, immigrant, disabled or other. For this reason, it seems appropriate to end this article with a discussion of Regina José Galindo’s 2008 performance America‘s Family Prison.

Regina José Galindo, America's Family Prison, 2008. Produced by ArtPace. San Antonio, Texas. Photos: Todd Johnson and Kimberly Abuchon. Courtesy of prometeogallery di ida pisani.

Galindo, a native of Guatemala, is best known for her performance work dealing with social injustice, treatment of indigenous peoples, and violations of women’s rights. For America‘s Family Prison, Galindo rented a prison cell from Sweeper Metal Fabricators Corp. and had it transported to Artpace gallery in San Antonio, Texas. For 36 hours, Galindo, her partner and her two-year-old daughter lived in the cell, which replicated those used by private prisons to detain families while their immigration status is determined. Galindo’s performance was a direct reference to the T. Don Hutto Residential Center, a for-profit family detention center located near Austin, Texas. Private family prisons, which speak to the migration and trafficking of peoples who are forced to displace themselves due to economic necessity, are the result of a post-colonial, transnational economy in which people and goods are moved around the world as needed. Galindo’s performance, in which she and her husband enacted an ethics of caring-for each other and for their daughter-suggests an economy of human interaction that is, for lack of a better word, maternal.

WORKS CITED

- Butler, Judith, Undoing Gender, Routledge, 2004.

- O’Reilly, Andrea, “Feminist Mothering,” Maternal Theory: Essential Readings, Andrea O’Reilly, ed. Toronto: Demeter Press, 2007.

- Ruddick, Sara, “Maternal Thinking.” Andrea O’Reilly, ed. Maternal Theory: Essential Readings, Toronto: Demeter Press, 2007.

Notes

1. Myrel Chernick and Jennie Klein, “Introduction,” The M Word: Real Mothers in Contemporary Art, Klein and Chernick, ed. Toronto: Demeter Press, 2011, 1-2.

2. Andrea Liss, Feminist Art and the Maternal (University of Minnesota Press, 2009); Myrel Chernick and Jennie Klein, ed., The M Word: Real Mothers in Contemporary Art (Toronto: Demeter Press, 2011); and Rachel Epp Buller, ed., Reconciling Art and Motherhood (London: Ashgate Press, 2012).

3. Dear Gabe can be viewed at snag films <http://www.snagfilms.com/films/title/dear_gabe>

Jennie Klein is an associate professor of art history at Ohio University. She is the co-editor with Myrel Chernick of The M Word: Real Mothers in Contemporary Art (Demeter Press, 2011) and the co-curator, along with Chernick, of the exhibition “Maternal Metaphors II” (2007). She is currently working on two edited books on the work of Marilyn Arsem and the Love Art Laboratory—the brainchild of Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens.

Lovely article & so thrilled you included Courtney Kessel! She is an outstanding artist and her piece along side daughter Chloe, is wonderfully thought out, the exact personification that so many go through in life. The literal vision of balancing one’s life.