« Features

The Shadow of History and the Simulacrum in the Art of Andreas Angelidakis

“Do we even need architecture anymore?”

Andreas Angelidakis

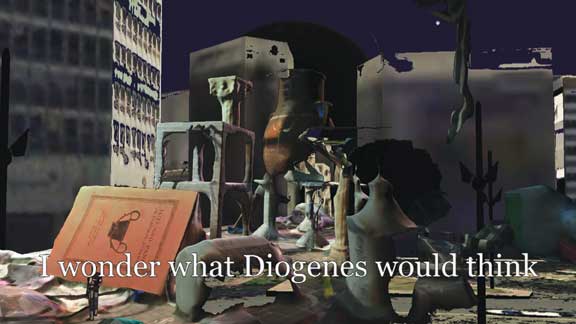

Andreas Angelidakis’s body of work, inspired by the city of Athens, continues to signify the shadow of history and the simulacrum in works like Vessel (2016), which is both a sculpture and an animated video. Humorously, it features a pithos, a large clay storage pot sometimes used for human burial, adapted as a shelter by Diogenes, a Cynic philosopher, c. 404-323 B.C.E. (Diogenes, unbathed and unshaven, dispersed an ongoing diatribe from his home in the pot.) Heralding a turn to philosophy, Angelidakis’ recent projects in Athens and further afield include Socratis Socratous/Plánetes at Pafos 2017 at the European Capital of Culture, which runs through February 2017. However, in order to analyze Angelidakis’ intellection over time, this essay focuses on certain works in his retrospective “Every End is a Beginning,” curated by Daphne Vitali and Angelidakis himself. The exhibition took place at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, from May 5 to July 13, 2014. Theorized here are “non-places” and “flows.” “Non-places” are defined by British philosopher Peter Osborne as a “recoding of the museum/gallery space as the location of an essentially abstract cognitive experience.”1 “Flows” are defined as virtual sites, digital images and defunct social media sites.

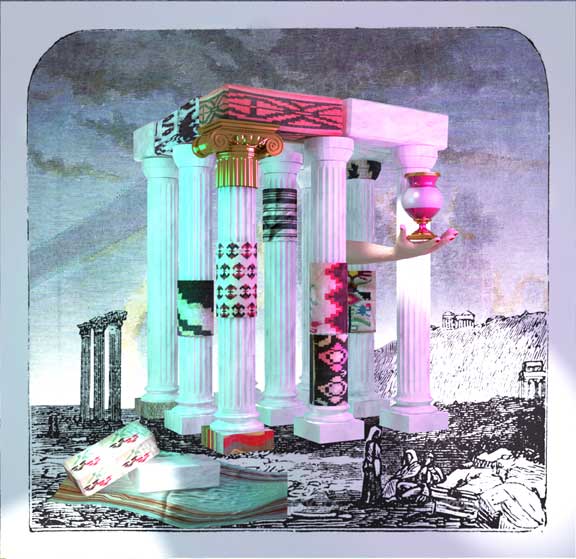

Of significance, Angelidakis, born in Athens in 1968, is described variously as an artist, an architect, a blogger and a designer of spaces virtual and real. Angelidakis uses the exhibition space as a medium to ask questions and think about the personality of Athens through his works, which he refers to as “Trojan Horses,” “to convey ideas from the Internet and history to the here and now.”2 For Angelidakis, Athens was becoming a non-site where banking, currency and markets would short-circuit. In Study for Crash Pad (2014), a plasticized pastiche of Doric columns surmounts an historical print of the Acropolis and surrounding area. Thrusting through it is a mall mannequin hand (found online by the artist) holding a vase, suggestive of the culture of tourism in Athens. The clandestine hand references the outstretched palm that makes an offer from the shadows, somehow gauged to be inappropriate or even politically dangerous. Does it refer to the gift by Alexander Iolas of his collection to the Greek state? Is it a critique of the unpayable debts Greece has incurred?

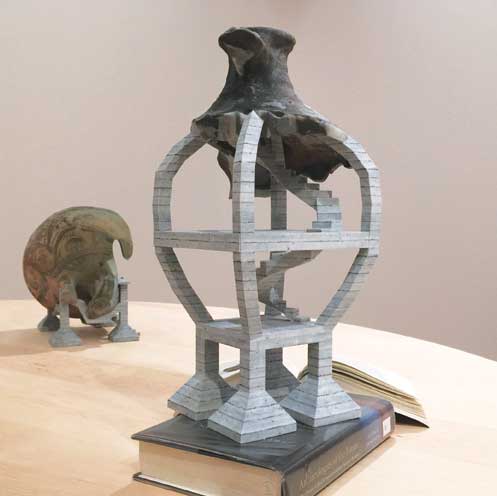

On his blog, Angelidakis ironically proposed that the Parthenon be sold to the Saudis to provide an influx of cash to Greece. As a replacement, there is his simulacrum Bone Domino (2014), a three-dimensional print that resembles a Doric temple made from turkey bones with a wishbone on the roof to simulate the cornice of the Parthenon. This may be a sly comment on the theory proposed by George Hersey and Sharon Kivland that the architectural order of Greek temple architecture simulates early pagan practices of hanging the bones, horns, teeth, eyes and entrails of sacrificial animals in trees. Thus, the columns are reminiscent of tree trunks, and other elements of the classical order may be conjectured.3

While Hegel held that a sign “is an image that stands for its recollections,” stimulating the imagination as “the first reflexive movement of consciousness,”4 the Parthenon is a symbol of great achievement in architecture, the founding of democracy and the lasting contribution of Greek philosophy. In this light, as Søren Kierkegaard wrote, “The ironic to the first power lies in the erection of a kind of epistemology that annihilates itself.”5 Ergo, Angelidakis deployed irony to make the National Museum of Contemporary Art appear to be already closed before its intended move to its purported new home, the former Fix Brewery. To achieve this, he draped the wide stairwell leading down to the cavernous galleries with scaffolding and orange construction netting. Here a connection can be made to Slavoj Žižek’s talk On Architecture and Aesthetics (2010), in which Žižek spoke of how being seen at an elite event walking down a stairwell creates “surplus pleasure.”6 The “surplus pleasure” of being seen or seeing others on the staircase perhaps was operative at the opening reception, but in the absence of a crowd, the sound from the videos playing simultaneously in proximity to Angelidakis’ self-directed retrospective was sinister, like waltzing with the shades.7 Was the exhibition space a metaphorical underworld? Footsteps echoed in its vastness, but visitors and museum guards remained unseen. The sound of the footsteps seemed to be coming from the avatars populating the artist’s digital works.

Do the avatars represent the artist as he moves virtually through the spaces he designs, or are the avatars objects of desire inhabiting the digital realm? In one immense, shadowy chamber, a number of tall, narrow, topless, sepulchral forms (System of Objects, 2013) spoke of internment and airlessness.8 Hypothetically, in the context of the museum closing, these structures could stand for emptied museum storage vaults. The theme of abandonment continued in the broken-down museum bathrooms.

Uncannily, when Žižek spoke about toilets in his 2010 talk On Architecture and Aesthetics, relating the differing ways that French, Anglo-Saxon/American and German toilet bowls function, it now resonates with the defunct bathrooms in the National Museum of Contemporary Art and the tanked Athens economy. In fact, Žižek’s statement that signs of imperfection in architecture are erotic correlates with Angelidakis’ oeuvre. How? Just as Žižek found the ruins of the Parthenon, viewed through the glass walls of the New Museum of the Acropolis, to be erotic (after all, Zeno, founder of Stoicism, thought Eros stood by to protect Athens),9 Angelidakis’ many ruins evoke pleasure through their suggestiveness of scandals, secrets and erotic liaisons.

Let us follow this thread. For Žižek “Much more is at stake in architecture since it materializes public ideology (the obscene secret).”10 In Angelidakis’ video and installation entitled Iolas-a funereal space adjacent to the gallery of crypts-golden drapery and gold-covered armchairs framed archival film footage of the elegant Alexander Iolas as he moves dreamily through his villa.

The eerie filmic presence of the famous Iolas, an international art dealer and collector of art and antiquities, is overlaid with collages of nature and the text “then came the scandal.” The “scandal,” according to collector and philanthropist Dakis Joannou, who knew Iolas well, was that certain of Iolas’s treasures were caught in the time warp between the days when objects moved freely across borders (for example, most of the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and the institution of regulations on provenance and the movement of antiquities.11 Žižek asks, “What truths do buildings articulate?”12 Angelidakis’ video resurrects Iolas’ villa, designed and built by the Greek architect Dimitris Pikionis, along with artist Yannis Tsarouchis, as a purloined site. The artist populates it with specters of thieves and a disembodied mannequin arm that removes the treasures. The then Minister for Culture, Melina Mercouri, purportedly took offense to Iolas’ summation that Greek contemporary culture was “vulgar” and simply ignored Iolas’ offer of his collection to the Greek state.13

On another screen, Angelidakis animates Iolas’ phonebook, found in the Egyptian-born Greek’s ruined villa. The pages reveal names, telephone numbers and addresses of Iolas’ contacts interspersed with views of the ruined villa, intimating a clue in the search to reveal “the scandal.” The animated phone book adds to the mystery of why the Greek state refused to accept Iolas’ offer to donate his villa and collection. Was some of the art, like that which Iolas collected in the 1950s and the 1960s, unappreciated by the Philistines who ignored it? Was there a villainous plot afoot? Angelidakis’ video seems to reconstruct a crime scene. Mercouri’s publicized efforts during the 1980s to have the Parthenon marbles returned to Greece from the British Museum are well known. Angelidakis hints that other treasures were being taken away from Greece under her very nose. Are Angelidakis’ avatars simulacrums of Iolas’ shadow lovers, or are they tomb robbers? All the rumors are true, in a certain sense, according to Adrian Dannatt, the major contributor to the 2014 catalogue Iolas, prepared for the exhibition “Alexander the Great: The Iolas Gallery 1955-1987.”

As in the Iolas video, in Angelidakis’ digital world, male avatars, whose form appears to resemble that of the artist, walk up and down stairs into disjointed conduits that lead to spaces that are non-places, such as a length of tunnel thrown up on stilts or pilotis, void of function. Angelidakis suggests that the ruins he creates are fragments inherited from economic and political chaos and loss of belief in the idea of buildings to preserve the present or envision the future. He points out that the Fix Brewery, designed by Greek architect Takis Zenetos in the late 1950s, built in 1960 and bankrupted in the early 1990s, became the property of the Greek state. In 1994, the property was transferred to “Attiko Metro,” and almost half of the building was demolished to make way for a parking lot and ticket booths.

The remaining truncated structure, listed as a heritage site, is the new home of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, even if in 2014 the possibilities to reopen the museum at its new headquarter were at some unconfirmed point in the future.14 The whimsical cover of his self-designed catalogue for “Every End is a Beginning” features Fix (2014), a simulacrum of the Fix Brewery, created with three-dimensional modeling technology. It has the appearance of a salt-encrusted toy barge, perhaps hinting that the sea will embrace it before it ever houses exhibitions again. Furthermore, on the back cover, the artist has written a text in his own handwriting supporting the idea that “Architects who aim at employing themselves with their hands without the aid of writing will never be able to achieve authority equal to their labours.”15 Angelidakis ponders: “The real building is in the architect’s mind. The constructed building is a simulation of the architect’s idea. Architecture treats reality as a space of simulation, a video game. The authentic building exists only in the architect’s mind.”16

Supporting Angelidakis’ thesis, Peter Osborne argues that since technology allows communication without the need to be physically present in a place, the place loses significance as a source of social meaning and becomes a “non-place.”17 An exhibition of video works by Bill Viola was to follow Angelidakis’ retrospective at the museum. The irony is that Viola’s videos speak of a spiritual realm, a life after death, a morphing from one state to another. However, in 2014 the museum was closed, and the possibility of its resurrection or afterlife was uncertain. Osborne contemplates “post-architectural urbanism,” calling it “a qualitatively new spatial form”18 that corresponds to both Deleuze’s concept of “any space whatever,” implying disconnection and emptiness, and to the types of non-places Angelidakis has constructed both virtually and as 3-D models. A fantastical example is Cloud House (2014), a 3-D print and model for a vacation home based on the shape of a cloud found on the Internet, “but the idea comes from growing up in the Greek summer landscape of semi-abandoned and unfinished haphazardly constructed concrete domino frames on pilotis,” Angeldakis recounts on his blog.19 In Hand House (2014), another 3-D print, the ubiquitous mall mannequin arm juts out of the structure, holding in its palm a flat-topped, open-aired pavilion peopled by avatars. Hand House resonates with the second-century A.D. scholar Festus’ concept, cited by Indra Kagis McEwen, of a summum templum as “the place from which one contemplates” or views on all sides and which, in turn, being prominent, is visible from all sides.”20

Today, this form of contemplation takes place on the Internet. In a different context, Valérie Gonzalez theorizes that “the Greek word for sensation ‘aesthesis‘ (the root of “aesthetic”) suggests aesthetic qualities are those that we appreciate in perception: the sensory, structural, and spatial ones.” The effect of this, she writes, stimulates “the cognitive power of imagination.”21 Imagination is engaged, according to Žižek, when there is a secret that cannot be discussed openly. However, it is revealed in architecture built at the time. For Žižek, architecture explains the situation of the people. Therefore, Angelidakis’ non-functional structures signify non-places and the flows that render architecture virtual have importance. Consider Building an Electronic Ruin (2011), a video animation created by Angelidakis on a program called Second Life. It exemplifies that while an electronic building may erode digitally, or become lost in time like the disused social sites Friendster and Myspace,22 it can hold an erotic charge, perhaps hinting at digital congress. Angelidakis screened Building an Electronic Ruin high on the wall of a dimly lit gallery with mattress-like forms heaped up on the floor and against the walls as part of the installation Crash Pad (2014), itself a reference to the migrants seeking shelter as they flood into Greece.

The adjacent gallery housed another component of Crash Pad, featuring a space of truncated white columns, carpets and textiles covering or draping all surfaces. Greece’s bankruptcy in the late 19th century, repeated in the 1960s and again in the early 21st century, is framed by Crash Pad. Angelidakis explains that it is “based a little more on the taboo capacity of the Greek State, which never shook off its Ottoman identity, and remains to this day a European Union member state under examination.”23

From his orchestration of a body of innovative and critical art, it is observable that Angelidakis as curator retains the artist’s aura in the way that Boris Groys proposes that, “The museum exhibition can be made into a place of openness, of disclosure, of unconcealment precisely because it situates inside its finite space, contextualizes and curates images and objects that also circulate in the outside space; and in this way, it opens itself to its outside.”24

Apropos to this statement is Angelidakis’ video Domesticated Mountain (2012). It depicts a virtual house created by Angelidakis out of cardboard delivery boxes from Internet purchases, commenting on how suburban housing, situated around transportation corridors and fueled by shopping, rages on the Internet. Of course, as Angelidakis puts it on his blog, Domesticated Mountain becomes a ruin, swiped by the hand of a mall mannequin that moves across the keyboard. The artist revisits the idea that functional buildings are not necessary in a virtual world, where it is possible to order the world from a screen or flow. Indeed, animation creates its own world, as evidenced in Troll, a social housing block known as Hara and designed after Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation, built architects Spanos and Papailiopoulos in 1960.25 Angelidakis animates the ruination of this apartment block into a mountain, overcome by plants and trees, that lumbers out of Athens, accompanied by a powerful soundtrack like that of a Cyclops in pursuit. Art historian and the exhibition curator Daphne Vitali asks, “What roles can virtual and actual architecture play today?”26

In response, Angelidakis stated that nostalgia is of interest to him “as a psychological dimension that…mixes up moments in time into a new, non-chronologically organized landscape.”27 For Žižek, it is a large city (like Athens) that is most sustainable, while exemplifying the split between ancient history and subsequent building. Angelidakis created many models that are open, transparent and already ruins since they are non-functional. Žižek’s talk began with the idea that, “The safest way to ruin a work of art is to complete it.” For Žižek, “empty spaces with no function can be used as a space of freedom, imagination and struggle.”28

For Angelidakis, “Ruins are alive.” They can run away from the city. In this there is a warning. Angelidakis’ animated video Casinoruin (2014), narrates how a state-funded hotel supported by the Marshall Plan failed, since it was only shored up by Cold War politics.29 It bankrupted, was saved and then became a casino that also failed. He asks, “Was it an accident that a building meant to promote the Greek economy, came to illustrate its failure…a networked ruin…a billboard for the Greek economy [over time]?”30 The gap between the self and the constructed self that Žižek refers to echoes the reality of contemporary Athens. When Žižek changed the architectural adage “less is more” to “less for more,” the innuendo could be to how cheap, hastily built housing in Athens is now part of the body of the city. Elsewhere, Angelidakis is critical of the now abandoned mega-expensive Olympic Sports Complex built at a cost of approximately 9 billion euros for the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens.31 Glorious as it was, Athenians were burdened with a debt so great there was no funding to develop the facilities for re-use. It has fallen into ruin and is overgrown with weeds.

In conclusion, “Every End is a Beginning” created a conversation about political, economic and architectural history in Athens over time, simulated by the idea of the commons. The artist says, “If all those who have come to live in Athens cease to be termed immigrants and we call them Athenians, the psychology of the city will change radically. Athens, with all of its negatives, has become a city completely distinct from the others in Europe, and all it needs to do is embrace its personality.”32

Angelidakis points out that Greece, like the rest of the world, has an uncertain future. In retrospect, Angelidakis’ Monument to an Oncoming Disaster (2010) can be read visually as an ATM about to be overwhelmed by the tsunami of the 2015 Greek financial crash. Virtually, the disembodied hand that strokes the keyboard, dreams and desires and conjures the technological world as an experience has much to do with the curatorial hand of Angelidakis and his realized desire to “design exhibitions as experiences.”33 The installations, the video animations with their strident soundtracks and dubbed text, the three-dimensional prints and the mixed-media sculptures formulate a coherent Stoical statement, unflinching no matter what. “Every End is a Beginning” references a maze of dead ends in Athens and, by extension, in the contemporary world. Sumptuous architecture and substandard buildings end in ruins, and the ruins themselves become rendered in three-dimensional prints and animated videos. The artist’s rhetorical question, “Do we even need architecture today?” extends to the argument that young artists do not need museums or galleries today since their work is in the clouds of the digital realm, (finally godly?). Angelidakis’s work is coherent, smart, funny, ironic, sinister and highly informative epistemologically as a plane of immanence to extrapolate the archaeology (in a Foucauldian sense) of Athens over time. In his evolving animations and Internet works (flows) and in his 3D print architectural models (non-places), Angelidakis continues to forge new beginnings imbued with the critical humor of Diogenes.

Notes

1. Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013, p. 112.

2. Andreas Angelidakis and Daphne Vitali, “A Conversation on the occasion of the exhibition ‘Every End is a Beginning’,” Andreas Angelidakis: Every End is a Beginning. Athens: National Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014, p. 27.

3. George Hersey and Sharon Kivland, George Hersey & Sharon Kivland, Spring Hurlbut: Sacrificial Ornament. Lethbridge, Alberta: Southern Alberta Art Gallery, 1991.

4. Jennifer Ann Bates, Hegel’s Theory of Imagination. Albany, NY: State University of New York, 2004, p. 56.

5. Søren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates, together with Notes of Schelling’s Berlin Lectures. Edited and translated with Introduction and Notes by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989, p. 59.

6. Slavoj Žižek, On Architecture and Aesthetics, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdbiN3YcuEI (accessed December 11, 2014).

7. In a June 16, 2014, interview with Alexandria Pierce, art collector and museum patron Dakis Joannou observed that, “Greece is always associated with its mythology, so why not embrace it?”

8. These were first displayed as unique structures in The System of Objects: The Dakis Joannou Collection Reloaded by Andreas Angelidakis. Nea Ionia, Athens: Deste Foundation, 2013.

9. Slavoj Žižek, On Architecture and Aesthetics, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdbiN3YcuEI (accessed December 11, 2014). Based on Žižek’s story of a man at a restaurant requesting “a bed for two,” in his sexual anxiety, perhaps Žižek, in his own anxiety, was referring to the view of the houses and flats (perhaps “love nests”) at the bottom of the Acropolis.

10. Slavoj Žižek, On Architecture and Aesthetics, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdbiN3YcuEI (accessed December 11, 2014).

11. Interview with Dakis Jouannou, Athens, Greece, June 16, 2014.

12. Slavoj Žižek, On Architecture and Aesthetics, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdbiN3YcuEI (accessed December 11, 2014).

13. Interview with Dakis Jouannou, June 16, 2014.

14. Neli Koutsandrea, Urban Frame no 1: The “amputated” Fix brewery and the National Museum of Contemporary Art of Athens,<http://athensinapoem.com/2014/07/13/urban-frame-no1-the-amputated-fix-brewery-and-the-national-museum-of-contemporary-art-of-athens/> (accessed November 28, 2014).

15. Indra Kagis McEwen, Vitruvius: Writing the Body of Architeture. Cambridge, MA, and London, England, The MIT Press, 2003, p. 33.

16. Daphne Vitali, editor, in collaboration with Andreas Angelidakis, Andreas Angelidakis: Every End is a Beginning. Athens, Greece: National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST), 2014.

17. Osborne, pp. 134-136.

18. Osborne, pp. 133-141.

19. See, http://www.angelidakis.com/_PAGES/CloudHouse.htm (accessed January January 23, 2017)

20. Indra Kagis McEwen, Vitruvius: Writing the Body of Architecture. Cambridge, MA, and London, England: The MIT Press, 2003, p. 28.

21. Valérie Gonzalez, “The Comares Hall in the Alhambra and James Turrell’s Space that Sees: A Comparison of Aesthetic Phenomenology,” Muqarnas, Vol. 20, (2003), p. 260.

22. Andreas Angelidakis and Daphne Vitali, “A conversation on the occasion of the exhibition, ‘Every End is a Beginning,’ Andreas Angelidakis: Every End is a Beginning. Athens: National Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014, p 15 - 17.

23. Angelidakis and Vitali, p. 23.

24. Boris Groys, “The Politics of Equal Aesthetic Rights,” Spheres of Action: Art and Politics, edited by Éric Alliez and Peter Osborne. Cambridge, MA.: The MIT Press, 2013, p. 150.

25. Angelidakis and Vitali, p. 25.

26. Vitali, 25.

27. Angelidakis and Vitali, p. 19.

28. Žižek, On Architecture and Aesthetics, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdbiN3YcuEI (accessed December 11, 2014).

29. Casinoruin is an abbreviated online version of Casino/Networked Ruin, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RBFX-bWb5ws (accessed December 14, 2014).

30. Casinoruin, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKuaSodQ0uw (accessed December 17, 2014).

31. See photos at https://www.theguardian.com/sport/gallery/2014/aug/13/abandoned-athens-olympic-2004-venues-10-years-on-in-pictures (accessed January 7, 2017).

32. Angelidakis and Vitali, p. 25.

33. Angelidakis and Vitali, p. 29.

Alexandria Pierce earned her Ph.D. in the department of art history at McGill University in 2003 and now teaches 20th-century art history and graduate courses in art criticism and contemporary art at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Her reviews and essays have appeared in the Athens Journal of Humanities & Art, esse and Art Papers.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.