« Features

Tracey Snelling: An Urban Narrative

Many contemporary artists, especially those who work with videos, rely on storytelling and the narrative that flows from it. Tracey Snelling is one of these artists whose work is structured based on a story. Her unique scale models are made from imaginary buildings, sometimes creating small towns. These buildings show fragments of movies in their windows, provoking spectators to look inside, establishing a relationship of complicity with them through voyeurism. The viewer is puzzled by the stories behind each of the characters that inhabit these “buildings” and the connection among them. In this interview I asked her about what influences her works, as well as her recent projects and exhibitions.

By Irina Leyva-Pérez

Irina Leyva-Pérez: You went to school in California. Tell me about your formative years, and how do you think they influenced your current work.

Tracey Snelling - I initially attended photography classes in Northern California. The head instructor was from the school of Ansel Adams, however, we adopted the lab technician, Jacques Munger, as our mentor, who informed us of various alternative processes and other contemporary artists. It ended up being an amazing experience in that there were five or six of us that were pushing the boundaries, and each other, and experimenting with photography as contemporary art. Later, after I took a few years off to do conservation work with the California Conservation Corps and firefighting with the U.S. Forest Service, I returned to school at the University of New Mexico to complete my BFA. Here I was able to explore my work in depth and develop a stronger conceptual aspect to my art.

Tracey Snelling, Nothing (stills), 2012, short film, 15 minutes. All images are courtesy of the artist and Pan American Art projects, Miami.

I.L.P. - When did you start making models? You are a maker by nature, as all of your pieces are handmade, and you intentionally show the facture of the process. Is this something you do consciously or is it the result of the process?

T.S. - I refer to the buildings as sculptures, as they are not exact replications of places; rather, they are my impression of the essence of a place and the culture that it exists in. During university and for a while after, I worked with photography and collage for several years. In 1998, 1881 Chestnut Street, a collage I made showing a brownstone apartment building with many different rooms, became my inspiration to take the idea further and build a three-dimensional house. I covered the inside and outside with images from old Life magazines and wired the inside with lights. I continued to explore building sculptures and then photographing them. It felt like a very natural progression. Initially, the handmade aspect was the result of the process. As my work has evolved and grown, I have chosen to keep this raw quality as it reflects what I find so intriguing in the places that I build: the weeds growing up through cracks in the pavement, peeling paint on an old sign, a well-worn mattress in an alley. These are all signs of lived-in places. The pristine or too finely manicured don’t have much appeal to me. Often, my sculptures don’t look ‘complete’ until I have added the final layer of dirt and grime.

I.L.P. - There is certain voyeurism in your work, especially in the buildings where you have films in which people are ‘living‘ their lives, technically unaware of your presence. When we look at your pieces, one can‘t avoid the thought of wanting to know more about the protagonists in them. There is always something going on, a hidden story. The narrative behind a work is very important. Do you consider it lineal or fragmented?

T.S. - I don’t think of narrative in a lineal way in my visual art, with the exception of my short film Nothing and a few video works that I have made. In the sculptures, there is either a moment in time or a span of time that has no limit, although it’s usually the latter. With a sculpture that looks at one place, such as Flag House, Albuquerque, I had originally taken a photo of this rundown house in Albuquerque that had a huge American flag mural on the exterior. When I began to build the small version of it, I imagined the person who might live there. I chose a young man in his early 20s who had porn and heavy-metal posters on his bedroom wall, drank lots of beer, had a sink full of dishes and a handgun laying around. I was somewhat influenced by Larry Clark’s ‘Tulsa’ series and by the film Gummo. On the other hand, while working on a sculpture like Mexicalichina, which has many merging buildings representing Mexico, China and California, there is a large cast of very vague characters, from the stereotypical to the unexpected. I also used a good amount of footage and images that I shot while in China and Mexico.

Tracey Snelling, Woman on the Run, 2008-2012. Large scale mixed media installation at the Virginia MOCA.

I.L.P. - There is a strong histrionic component in your pieces, especially in those in which you are the protagonist. I am thinking specifically about Woman on the Run, in which you ‘played‘ the role of Veronica Hayden, a character created by you.

T.S. - Up until 2008, I had been using found footage for most of my video work, but for Woman on the Run I decided I would shoot all of the footage, using myself and my friends as the characters. By acting as Veronica I was able to shoot the videos whenever I needed to, rather than to rely on an actress. I also knew exactly what I wanted in that character, so it seemed like the best option. I like the quality of ‘home movie’ and overacted melodrama that comes from some of the clips. As Woman on the Run travels to different venues, and I, along with fellow Woman on the Run producer Idan Levin, add to the installation and continually change it, the idea of myself as Veronica becomes less important. At the most recent opening of the installation at Virginia MOCA, we had a young woman play Veronica and a man dressed as the detective. The idea of live performance is a new and exciting addition to the installation. Idan and I are further adding to the installation by collaborating on a site-conforming mystery called Woman on the Run Redux, which involves an iPhone application, among other things. Videos will play, telling a story that changes, depending on what one comes across first. This expands the idea of narrative and experience, helping the viewer to walk in the shoes of the main protagonist and the detective.

Tracey Snelling and Idan Levin, Woman on the Run Redux, 2012-2013. Sit-conforming installation with Iphone application and props. Clips from the Iphone application videos.

I.L.P. - Woman on the Run and Nothing are essentially stories of two different women. Do you usually write the scripts for your pieces?

T.S. - For Woman on the Run, the story evolved organically while I worked on it and continues to evolve. While working on Woman on the Run Redux, we came up with scenes and then had to consider how these relate to each other and what they mean when taken in different sequences. It’s a complex way of storytelling. When working on Nothing, I initially had the idea through images in my mind. I started writing notes, then wrote the linear description of the movie. Since there is no dialogue in the film, the ’script’ I wrote is basically about mood, setting, emotion and the actions that take place. We have started working on an idea for a feature-length film, but it’s in its beginning stages of forming the idea. Once we’re happy with the idea, we’ll move on to writing the script.

I.L.P. - There is a sense of past in your work, not only because you selected a poetic related to the 1930s but also to the slow tempo and music you use in your pieces. The fragments from movies also show a similar imagery. How is the process of selection? Is there a particular director you admire most or a writer whose books inspired you?

T.S. - It really varies, depending on which work. I’m drawn to many different eras and genres of film, so I use clips from 1950s film noir, great 1970s films, 3-D horror films, cartoons and even low-brow teen movies. When working on a sculpture, I will often have a few film clips in mind. Other times, I’ll do research on the Internet or visit the local video store. I am more attracted to specific films than directors. Some of those films that have influenced my work include Badlands, Fool for Love, Paris, Texas, Psycho and Touch of Evil, just to name a few. Music is also a big influence. When building Stripmall, Los Angeles I knew early on that I wanted to include clips of Scar Tissue by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Let’s Have a War by Fear and Let Me Blow Ya Mind by Gwen Stefani and Eve. All of these songs remind me of L.A.

Recently, I was invited to be in an exhibit called “The Storytellers,” curated by Selene Wendt and Gerardo Mosquera for the Stenersen Museum in Oslo and El Museo de Arte del Banco de la República in Bogotá. The curators were influenced by several Latin authors, so I decided to make sculptures based on literary works by some of these writers. It was a very interesting and enjoyable experience. The sculptures were somewhat different than most of my work in the past. In a way, it felt like I had a map of where to begin or go, although the choices around how to convey a poem or novel through a sculpture are so vast. For instance, the poem ‘The Parade Ends’ by Reinaldo Arenas captures the feeling of an empty, forgotten city with one lit room where the writer can still soar through his tappings on his typewriter. The sculpture is a small cross-section of an abandoned city, with tall, almost abstracted buildings with crooked windows and narrow alleyways. I wanted to make the sculpture more like a painting or sketch, even using charcoal to trace on the edges of some buildings. The colors are dark and dingy, and the occasional street lamp gives off an orange, eerie color as it flickers. In some of the storefronts videos of neglected places play, and the soundtrack is Arenas reading his poem in Spanish. Being that he was imprisoned in Cuba for many years, the piece and how it developed took on more meaning for me as it progressed. Once I added Arena’s oration of the poem, I felt a deeper emotional resonance with the work: one of sadness, yearning and, at times, hope.

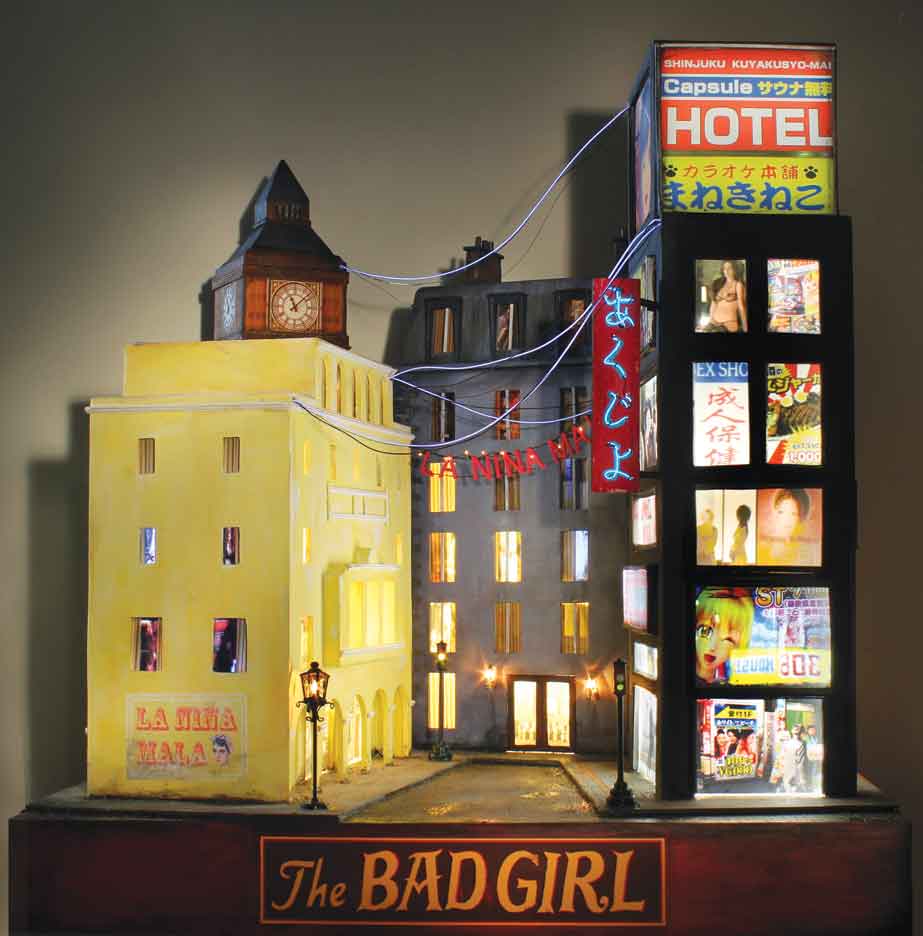

Tracey Snelling, Bad Girl, 2012, wood, paint, lights, electroluminescent wire, lcd screens, media players, speakers, transformer, 28" x 24" x 24."

I.L.P. - Architecture is a major influence in your work, and you always make your own buildings. Is there any particular type of architecture that you prefer? I notice that many of your pieces replicate motels and the culture that surrounds them. What inspires you to do that?

T.S. - Over the years I have begun to fall in love with quite ugly buildings. I continually find myself drawn to buildings that have aged and are in some kind of disrepair. It’s not necessary for them to have unique architectural characteristics. Hand-painted images and lettering are very attractive to me, as well as old signs, faded colors, and sometimes old brick or stucco. If I had to define the preference for older buildings, I’d have to say that there are many more interesting possibilities for stories within older buildings. In new buildings, the façade hides the stories too well. Motels are extremely interesting to me in that they are way stations for every kind of person. When considering how many people have stayed in one motel over a period of 20 years and all the crazy things that have happened there, it’s much more interesting than the contrast of a new hotel: people appearing to behave well in a nice, clean surrounding. Also, the mystery and excitement of being on the road is captured in motels. On another level, I try to capture a place that I am attracted to by building it. Even if it’s torn down at some point, I have some kind of documentation.

I.L.P. - You have done works exploring the interactions of two cultures, such as the installation Bordertown, in which you explore the relationship of cultures on the Mexican border with the United States.

T.S. - Since I was young, I have been fascinated with watching people and trying to figure out why they do what they do and what causes different people to have different reactions to things. This, along with my love for traveling to different places, inspires me to explore other cultures and landscapes. I also find it interesting to see how different groups of people living in the same place act towards each other. When I was young, my family moved to Manteca, a rural town in California. There was a large Latin population there, as well as where I live now. I’ve always been attracted to the culture, so it’s something I’ve explored in depth. Several years ago, I had the opportunity to stay in Tijuana with a Chinese family and to observe the Chinese community there and how they relate to their Latin neighbors. When traveling and observing different countries and cultures, I try to experience as much as possible, then to create a sculpture or installation that gives a full picture of the location, people and interactions.

I.L.P. - After your residency in China you have made a number of pieces that visually re-create aspects of its culture. What impacted you the most?

T.S. - I have done two residencies in China. The first was a three-and-a-half-month residency and solo exhibition with Urs Meile Gallery in Beijing in the winter of 2008/2009. Upon arriving, I traveled solo for a few weeks, visiting Yangshuo, Fenghuang, Chongqing and Shanghai. I then returned to the gallery to design and build the work for my show. Having both the support of the gallery (to help with art assistants and supplies) and living in Caochangdi, a village on the edge of Beijing, made for a unique experience where I was able to make some of my more complex sculptures and still experience daily Chinese life. I enjoyed China so much that I returned to another residency in Zhujiajiao, a river town an hour outside Shanghai, sponsored by the Shanghai Zendai MOMA (now Himalayas Art Museum). Only a month long, there was much less time to travel or create work, but after purchasing a bicycle, I was able to tour around the countryside and get a different view of life there. The museum and residency was fully staffed by Chinese employees, and communicating could often be challenging, but that was also part of the enjoyment of the experience. The things that draw me most to China are that it is so different from the U.S., and the people are so genuinely nice. I plan to return to China in the near future, and I also want to begin my exploration of India and Cambodia.

I.L.P. - What are you working on right now? What are your immediate and future projects and exhibitions?

T.S. - I am working on several different things at the moment. I’m building some new pieces that move away from the square structure to a more fluid, organic shape, and others that incorporate painting in a new way for me. We’re also in the final stages of developing Woman on the Run Redux and are discussing new additions for the installation and bringing it to the West Coast. Another idea I am exploring is using my sculptures as both subjects and backdrops for a new film. And I’m also in the initial planning stages for solo exhibitions at Pan American Art Projects in Miami (2013), Rena Bransten in San Francisco (October 2013) and Aeroplastics in Brussels (April 2014). At the moment, I am in exhibits at Muba Tourcoing in Lille, France; Museum Dr. Guislain in Ghent, Belgium; and Aeroplastics in Brussels, Belgium. Woman on the Run is on exhibition at the Virginia MOCA through the end of December. “The Storytellers” exhibition will travel to El Museo de Arte del Banco de la República in Bogotá in March 2013.

One more project I am working on is planning research trips to China, India and Cambodia in order to experience and document the places and eventually make a new body of work focused around these areas and some of their immediate concerns. I hope to begin some of the travel next year.

Irina Leyva-Pérez is an art historian, art critic and curator based in Miami. She has lectured at Edna Manley College and was assistant curator at the National Gallery of Jamaica in Kingston. She is currently the curator of Pan American Art Projects, a regular contributor to a variety of publications and author of catalogues of such Latin American artists as León Ferrari, Luis Cruz Azaceta and Carlos Estévez, among others.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.