« Features

Trenton Doyle Hancock: Prayer Warrior

By David Humphrey

If you tell yourself to do something, commandingly, can there be a good reason to resist? Are there advantages to having an unharmonious self? Trenton Doyle Hancock makes materially imposing artworks that stage a model of the self as a questionably disciplined collective. He uses cross-purposed behavior productively, both as a way to make paintings and as a metaphor for the self within history, dramatizing the ridiculous contingency of our lives.

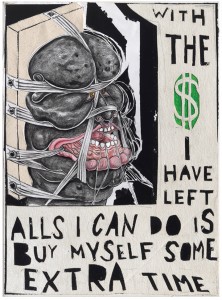

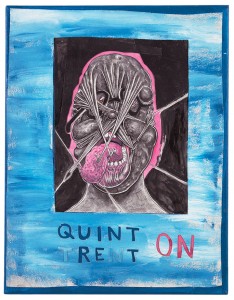

In the painting With the Money I Have Left, 2012, Hancock pictures the head of a man trussed to a board so that his soft flesh and oversized mouth bulge from between tight bonds that are tacked to a board, secured by nails running along its sides like a stretched canvas. Densely crosshatched black lines articulate the soft forms of our hapless protagonist and echo the trusses crisscrossing his face, sometimes getting inside his mouth and teeth like dental floss. The self-binding deepens in Quinton Trenton, 2012, as the trusses are now stretched from the head’s own flesh. Ouch! A small bone pierces the tongue to anchor a bond pulled from forehead skin, crushing Hancock’s signature black glasses onto his face. The drawing style is reminiscent of underground comics, but surrounding graphic paint gestures and irregularly bold collage borders declare both the absurdity of Hancock’s staged self-binding and the seriousness of his formal ambitions.

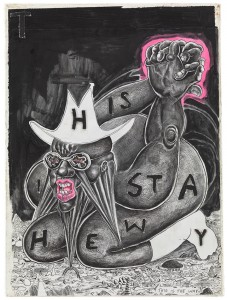

The man inside the image is commandeering the constraining effects of others by constraining himself. The artist’s desire, implied here, is shaped by the desires of others, incorporating the force of their expectations, including the pernicious legacy of race in America, but also reflecting the condition of every person as they grow up within family and community. Hancock’s images register these forces with lunatic and imaginative panache. The solitary hero in This Is the Way, 2012, is on his knees, facial skin stretched and anchored to the ground, demonstrating a yoga-like gesture. His hands are clasped behind him in backwards prayer with a halo of the same pink that highlights his open mouth. Pink appears frequently in Hancock’s work as a contrast to the form-describing role of black: pink becomes the principle of vitality, heat or raw interiority, like tears or a wound. Hancock’s images often seem broken down and rebuilt, repaired and corrected until they arrive at a state of cockeyed exuberance.

Hancock’s exhibition last November at the James Cohan Gallery in New York was hanging at the same time as mine a few blocks away immediately after Hurricane Sandy. My attention was arrested by the coincidence, in both our shows, of the image of a cat gripping a human in its claws, making wound-marks on the victim like a drawing. Predator and prey, figure and ground, become a hybrid organism at war with itself. But Hancock develops this theme further than I do, taking it to monstrous extremes that blur distinctions between public and private. On this morning, with my coffee, electronic New York Times and background of chattering birdsong, I learn that George Zimmerman has been acquitted, that T.J. Clark has a new book called Picasso and Truth, and enough additional news to overwhelm my day. The chirping birds are urging me to relax my appetite for coherence, to surrender judgment and notice the emergence of possibilities within a distended moment. In a painting though, the object is the moment; a moment that unfolds into a turbulence of other moments that include a piling up of pasts-the past of language and history, the past of the artist’s labor and of associations generated by spectators. I will contact Hancock’s gallery this afternoon, buy Clark’s book and arrange to talk with the artist. Hopefully, in a week or so, I will be able to focus on writing this article for ARTPULSE, in spite of my recent decision to quit writing about art. Picasso and Truth arrives quickly and Clark’s succinct characterization of modern art seems to illuminate Hancock’s work: fragmentation and a refusal of completion, tension without resolution, eruptions of explicit arbitrary violence, regression to the childish or animalistic (I will ask the artist about toys and fantasy). Hancock and I sort out a time and eventually have a conversation on Skype. He speaks with thoughtful care, laughs easily and takes himself seriously with a self-effacing touch.

D.H. - I gathered from my readings that your family is religious, that you grew up with Bible stories and churchly faith. You once used the term prayer warrior; is that an official Christian term or something that you made up?

T.D.H. - No, that’s a term I grew up hearing from my grandmother and my father and from people who basically stayed on their knees their whole life. I think they saw themselves at war with Satan and other demons. The only way to combat all of that was to have a very intense prayer life. They considered themselves prayer warriors. I don’t think people use it quite as much now, but when I grew up it was used by people that were in their 70s and 80s. I’m assuming that it was born out of a time when black folks didn’t have any recourse but to resort to prayer, the last resort.

D.H. - I like thinking of painting as having a magical potential to resonate out from a solitary studio activity into the world, like a prayer but detached from established religion, with an aggressive potential to make a difference.

T.D.H. - Yeah, I think my studio is set up according to the same rules that I grew up with. You dedicate your life to something; you sacrifice in a way one could describe with the language of martyrdom. I’ve developed a perspective over the way that I grew up, the whole Christian background thing. I don’t necessarily identify as such right now, but I think about it a lot. I think about what are the good things that I could take from that rigor or that lifestyle and incorporate it into my studio practice. I think there’s still a little bit of residue left over. I don’t want to say guilt, but maybe the fear that’s a deep Southern Baptist, black Baptist thing. It’s definitely not guilt-based, it’s more fear-based. I think there’s something interesting to be said about making a painting that you can fear for yourself for having made it.

The Former and the Ladder or Ascension and a Cinchin‘, 2012, elaborates an image of the artist as fallible actor with equivocal self-possession. The protagonist in sneakers and necktie marches toward us, tangled in a ladder, while turning back toward an oversized No. 2 pencil clutched in his hand. Words and numbers flow through the image, sometimes diagramming, naming, titling or signing the piece but altogether challenging coherence. No head emerges from the collar of the high-stepper’s striped shirt, but a pair of eyes floats just above within a cloudy turbulence of sinews and disembodied veins, seeing but perhaps not grasping. The ground in Hancock’s work, whether background or landscape surface, is a place from which threats or promises sink and rise, where nonsense and revelation jockey for position, and where matter plays across the boundary between the animate and inanimate.

D.H. - It looks like the jauntily dressed central figure in The Former and the Ladder or Ascension and a Cinchin‘ is trying to do something or get somewhere, but all the objects that could be helpful to him, like the ladder, are getting in his way.

T.D.H. - The ladder came in after I was evolving away from the fantasy material of my earlier work. I wanted to switch focus and say, “Okay, let’s turn the camera back on the maker. The protagonist in these paintings is now going to be me.” What could be a new anchor in a painting, and what could be a new environment in a painting? It’s like I had to refigure from the ground up how to deal with telling a basic story.

D.H. - Without a master narrative, perhaps?

T.D.H. - It’s like, how do you get there, and what’s the journey to get back to it? At that point, I started thinking about stories that I grew up with that weren’t biblical. My stepdad was not only a minister, but he built houses. I grew up partially on construction sites. When I would hang out as a kid there, if you walked under a ladder and he caught you he would make you walk back under the ladder backwards to undo whatever you just did. He passed away a few years back, so I’ve been trying to reconstruct him through memories and stories. There was a level of the prayer warrior stuff, things that were biblical and irreducible in his eyes.

D.H. - Officially sanctioned?

T.D.H. - Yeah, this is the truth. And then he was a black belt in karate, so there was a lot of Eastern influence in the way that he did things. It seemed antithetical to the Western Christian idea, but he was able to reconcile it all and make sense of it. Then there was this whole other level of him, which was the taboos and superstitions; certain things you don’t do. If he was still around I’d probably ask him, ‘So what would happen if I didn’t walk back through the ladder?’

D.H. - Would Jesus have a role?

T.D.H. - Yeah. Who exacts vengeance on you or punishes you? I decided to isolate the ladder and write about it and think about what it could mean in terms of being a portal to a space of the unknown.

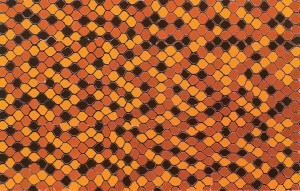

D.H. - What does the repeating pattern in the background of The Ladder refer to? I see that it is the main image in The Den, 2012, and recurs in a couple other paintings. My intuition is that you have very good reasons for doing everything, and it’s all part of a thick soup of reference and personal material. But in some ways, does it matter, at least from the viewer’s perspective? I feel there’s a rich and noisy hum of chatter that intensifies a promise of sense just out of reach.

T.D.H. - It was a tile floor. The pattern in the painting was a reconstruction of the floor in my grandmother’s house. It was a communal space, where the TV was, where my grandmother would sit and make her quilts on the couch, and it’s where I laid on the floor and learned how to draw. I’m drawing on the floor, I’m three or four years old, and I look up and my grandmother is doing her thing. There’s a call and response. It’s like I was swimming in the primordial muck right there on that floor, just forming myself.

D.H. - Could the painting be considered a kind of prayer that transports you back to a place of freedom without a story or granny? It’s a very big painting without the familiar Hancockian narratives, like a screen onto which content can be imaginatively projected, or maybe from which content emerges.

T.D.H. - Maybe it’s only in my head, but I consider myself to be a formalist in a lot of ways. I’m concerned with order, balance and construction of that balance. There’s a level of narrative that’s in front of it all, but when you break it down it is just a tile painting. This is, I guess, extending my range of what I’m capable of into consciousness.

D.H. - I’m thinking about Robert Farris Thompson and his writing on Afro-Caribbean culture and African-American content because I believe your work would interest him. So much narrative inflected by oral traditions seems to be sedimented in your work. Those shelves of toys I see behind you right now remind me of the way some artists try to make work out of a spirit of play. I’m thinking of the way kids, boys especially, use toy soldiers to stage battles guided by fantasy narratives, making the child both spectator and master.

T.D.H. - I’ve loved Paul McCarthy’s work for a long time. He’s managed to stay for many, many years in a state of arrested state development, at around 12 or 13 years old. He’s really mastered that space, not just 12 or 13 years old in general, but that really messy, confusing space specific to little boys, in which the body is not what you thought it was. You’re still a kid, so play is very real to you; you’re still playing with your army men, but you have porno under your bed. In my studio I feel like there’s still a bit of that. When I played with toys as a kid, though, it wasn’t that I set them up and acted out, it was more setting them up so I could look at what I had just done, a kind of voyeurism on my part into their world. I would set up things and then just move away from it, to see the whole panorama. It’s essentially the same thing that I do in the studio when I build a painting. You step back from it, and then you observe it. Most painters work that way.

D.H. - But you’ve turned that split into a theme.

T.D.H. - My girlfriend and I were just talking about Henry Darger, who sort of provided a blueprint for both of us in the way that we make our work. We were talking about how he puts himself into his works. He is the god and the creator of the whole thing, which he can ultimately destroy or create. But occasionally he places himself in the middle of the battle; sometimes he wins, and man, sometimes he loses. It’s the mirror within a mirror that I find interesting.

D.H. - Does graphic fiction or comic books do this for you?

T.D.H. - I have here the first comic I ever had, Spiderman; it just happens to be in my studio right now. My stepdad brought it to me when I was getting my tonsils out; I was in the fourth grade. I remember thinking, ‘This is so serious. This isn’t for play any longer.’ Because I think the treatment that I had normally seen of comic book characters was they’re on your bedspread or it’s a TV cartoon. Having this pulpy thing in my hand with reading involved seemed very grown up. There was a level of seriousness in the way it was drawn and the way it was written. It was a life-changing moment.

D.H. - I don’t know about you, but I surely like the idea of making a painting based on the question ‘What if?’ It means that making the painting isn’t just the execution of an idea, but the unfolding of a possibility. What about the cacophonous painting Black Mamba, 2012?

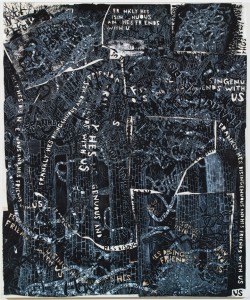

T.D.H. - If The Den painting is announcing a possible road we can go down, Black Mamba is expressing that same kind of potential spread of our dissemination of raw, possibly evil, information. It’s speaking both about the nature of Satan - he’s disingenuous and he’s friends with us - but also about the nature of painting and illusion. Just as Satan is described as a master of illusion, so is painting. Black Mamba is a self-portrait that acknowledges that this thing that I do is kind of disingenuous.

T.J. Clark writes, “Untruth in Picasso is always terrible. It is a pressure from elsewhere-collapsing space, producing disfigurement. It is a condition, a fate, a thing entering the interior of the mind.” Trenton Doyle Hancock shares with Picasso what Nietzsche called ‘the will to deception [with] good conscience on its side’ in order to fuel what Clark calls ’sheer coercive inventiveness…sheer effect, sheer unprecedentedness.’ (David Humphrey)

David Humphrey is a New York artist who has shown nationally and internationally and received a Guggenheim fellowship and Rome Prize, among other awards. An anthology of his art writing, Blind Handshake, was published by Periscope Publishing in 2010. He is a senior critic at the Yale University School of Art and represented by Fredericks & Freiser gallery in New York.

* All images are courtesy of James Cohan Gallery, New York and Shanghai.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.