« Features

Visual Narratives: An Interview with David Humphrey

David Humphrey is a New York-based painter who also writes art criticism. He received a BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art, studied at the New York Studio School, and finished up with an MA from New York University. He’s received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Rome Prize, NEA Fellowships and other awards too numerous to mention. Blind Handshake, an anthology of Humphrey’s writing, was published in 2010. He is represented by Fredericks & Freiser gallery in New York and is a critic at Yale University. On this day he agreed to give us a Skype interview from his Long Island City studio.

By Craig Drennen

Craig Drennen - First, I want to thank you for breaking up your studio time for this interview, and I’m curious what you’re working on now.

David Humphrey - We’re talking on Skype, so I could actually just walk around the studio and show you things.

C.D. - Are you prepping for a show?

D.H. - I have a show that just opened two days ago in Gainesville, Fla., at a new gallery called Protocol that was curated by Linda Norden. It’s a not-for-profit art space that is attached to a residency and an interesting plot of land. The show is called “A Horse Walked Into a Painting,” and Norden focused on an aspect of my work having to do with the theatrical relationship between a setting and the protagonists. I’ve worked with this crude binary of ‘Where is it?’ and ‘Who’s in it?’ for many years. Sometimes the location acts as a protagonist and the characters might be passive witnesses. I’m continuing to work with the image of the spectator as protagonist. Often it’ll be as simple as somebody in the picture looking at something, like an overturned cement truck or a closed door.

C.D. - One of your surrogates?

D.H. - Yes, spectator surrogates. I’m working on a painting now with a topless woman sitting in a chair looking at a large coral on the floor filled with many small horses. I haven’t really figured it out yet. One of the ways I tend to work is to develop an image in search for what it could possibly mean. So while I’m working on it I have trouble summarizing what it’s about or putting it into any kind of context because the process is an occasion to have an adventure.

C.D. - That’s perfectly admirable and runs counter to some tendencies in fine art education-to welcome ‘unknowing’ in the beginning of the process.

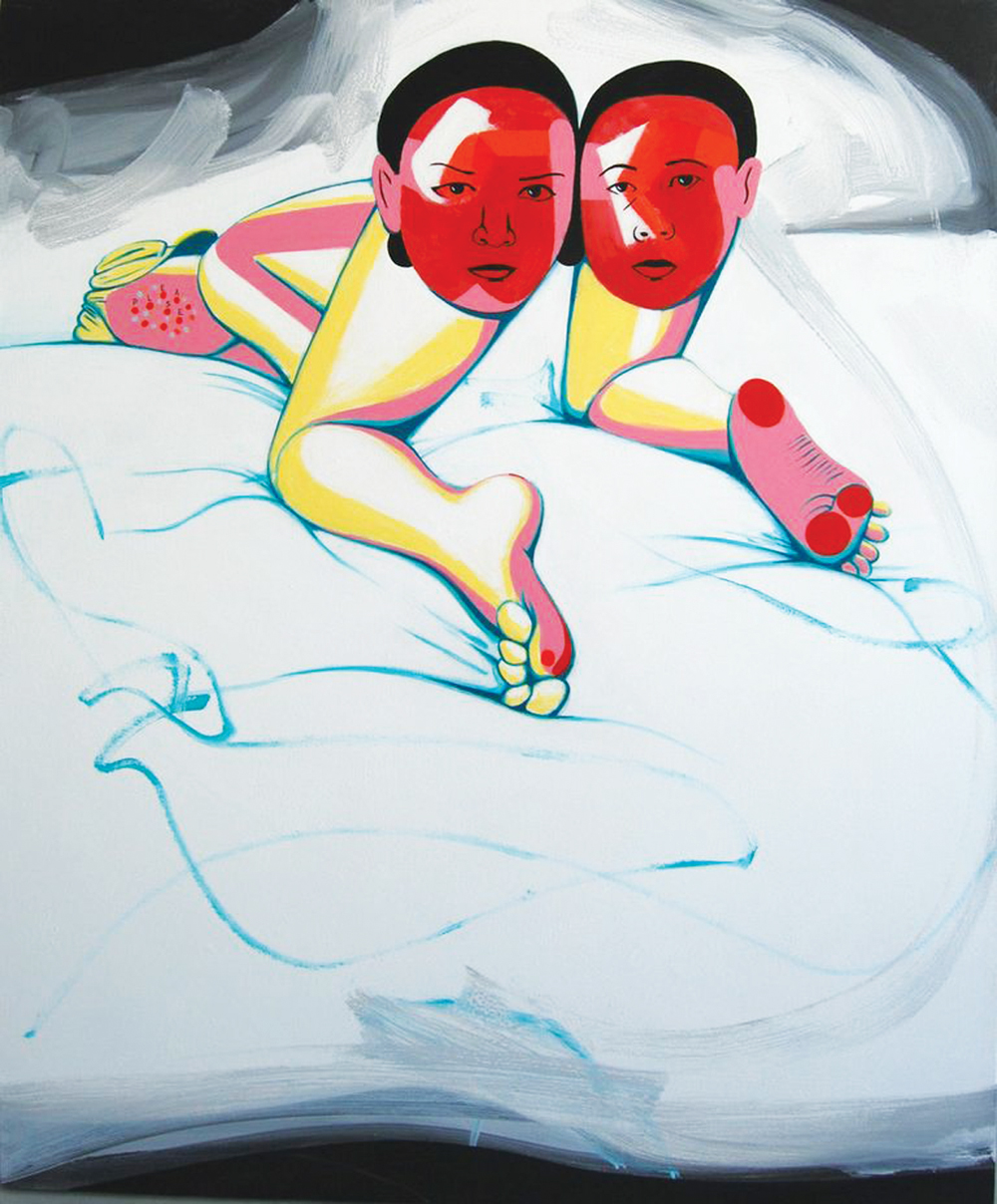

D.H. - It’s a challenge to craft an open-ended painting situation so that possibilities emerge. Reflecting on the condition of the spectator is broad enough to do that. I guess something I’ve come back to over and over is an attempt to stage intersubjectivity-what happens between people. Sometimes there will be two people in the piece who are entangled, maybe they’re fighting or in love. I’ve done some images recently of people struggling with each other.

C.D. - I don’t mean to interrupt, but that sounds like something that poets say. What you’re describing-two characters in a scene-strikes an emotional chord that I associate more with contemporary poetry than with current painting.

D.H. - Yeah? Well I think there’s a modernist side to it in which different idioms or modes of representation are used like characters in fiction. You can have different languages within a picture relating to each other with a kind of psychosocial content.

C.D. - What I’ve always liked about your work-the shows I saw when I lived in New York and the shows I’ve seen in Georgia-is the fact that the figures always seem like they’re performing a task. I like that they don’t just sit in the pictures and do nothing. There’s something important that they’re trying to do, and it might just be a horse humping a snowman, or in an older painting like Snow Boy the boy is gathering his arms around all the little figures. There’s always some action important to the characters themselves, and to me that’s always been the portal into the work.

D.H. - Well I hope so. Sometimes the character inside the picture will be a caregiver, as if somebody else in the picture needs help. Sometimes the painting itself needs help. I like to somehow create a fiction of the artist; I’ll use gestures sometimes so that the ‘author effect’ resonates inside the narrative.

C.D. - I think that reads clearly. And it’s been interesting to witness the change from the 2004-05 pieces up to the present. Because now I really do feel that the abstract marks are easy to read as characters, more so than in the previous work.

D.H. - I hope so. I like the idea that the painting can unravel, that it can become undone so that a state of disorder is part of what the painting means.

C.D. - If you’ll permit me the analogy, there’s a bit of the old Tasmanian Devil quality from the old cartoon. When he’s spinning he’s an abstracted tornado of shapes and lines that’s powerful and crazy. But when he stops he becomes an image that’s understandable again. And then he can become crazy and abstract again.

D.H. - That’s good!

C.D. - So there is a bit of that same quality is in your recent pieces. I’m forgetting the title of the ones I’m thinking of. Maybe they were called Retouch? Is that possible?

D.H. - Mmmmm. Yes. That does sound like a title I would use. One touches. One retouches. I did a whole series back in the early 1990s that were photo-based paintings and I used this idea of retouching as it relates to memory, to the photo and as a way to reach into the image. It was a way to talk about contact within the fiction of the picture.

C.D. - I love that term and the idea of ‘retouching.’ Many associations emerge from that word. If you don’t mind, I’d like to recount your education. You went to MICA, then the New York Studio School and then finished at NYU before branching out on your own. I have a really broad question: Do you feel that your formal education prepared you to be an artist?

D.H. - I would say not in the slightest.

C.D. - (laughs)

D.H. - But it did put me in the context of making work all the time, with a giant appetite to absorb and grow. In school I felt behind. I didn’t have much training in high school, so when I arrived at MICA everyone else seemed to know what they were doing. I’d never done any drawing, for instance. I had done stone carving.

C.D. - You arrived as a sculptor, right?

D.H. - Yes, I arrived as a sculptor, but they didn’t let us make sculpture until sometime deep in the sophomore year. So by the time I got to that stage I was up and running as a painter and draftsperson. The Studio School was an interesting augmentation because it was a direct transmission of the values of Hans Hoffman and a kind of perceptual painting underwritten by formal abstraction, as it rolled up through Cezanne, Cubism and the Studio School’s version of Abstract Expressionism. I was trying to do something that was more loaded with content. I was excited by Beckmann, late Picasso and Guston, and the school wanted nothing to do with that. They discouraged me.

C.D. - What about Picabia? He probably wasn’t on the table at all.

D.H. - Picabia was barely on the table. I knew the early machine landscape Cubist paintings at MoMA-those giant ones. But as a student, I really wasn’t aware of the very strange crappy hybrid paintings that became important in the 1980s. I loved the nudes especially.

C.D. - Since you mentioned the 1980s it permits me to talk about that time. That decade, when you first started to exhibit, seems like an amazing moment to be a young painter. One of my habits is to collect exhibition catalogs from the late 1970s and early ’80s, and that time period always feels more vibrant and alive and contested than the art historical narrative now indicates. You were in a show at Gladstone in 1984, weren’t you?

D.H. - I was in a group show at Gladstone in 1984 called “New Hand Painted Dreams” curated by Richard Flood. Dan Cameron wrote an article at the same time about Neo-Surrealism. So the Neo-Surrealist show at Gladstone was looking for a style echo of Neo-Expressionism. It was a non-movement, but there seemed to be a spontaneous preoccupation by many artists with revisiting discarded historic styles.

C.D. - That’s what I was wondering. Because in some ways it feels like ‘Neo-Surrealism’ was a way to intellectually rationalize the practice of pastiche-bringing in things from different historic styles and reconciling them within one work. That seems like a huge idea that painters at the time were wrestling with.

D.H. - It seems like it came along with the exhaustion or general collapse of the model of the avant-garde, the imperative of artists to overthrow the generation before and find ever more radical rethinkings. Sometime around 19-whatever-late ’70s maybe-young artists began to feel very constrained by that model. I never thought as a student that there was a place for what I was doing in the art world.

C.D. - I’m surprised to hear that.

D.H. - Well this was the late 1970s. The art world was a lot smaller, and I certainly wished for a place in it and felt that there ought to be a place for me in it. But the most advanced galleries were showing super-reductive work or conceptual work, so whatever it was that I was doing didn’t seem to belong. But as it turned out, I was part of a broader generation of people coming into the art world from all kinds of angles.

C.D. - With all the other things that were going on-like the Times Square show, the East Village galleries, the scene in Soho-it just seemed like a great time to be a young painter. But maybe I’m applying nostalgia to it because I’m a generation behind.

D.H. - It’s so funny, because I think there’s a lot of young art out there right now that’s very exciting, and at the grassroots level things are thriving even as people are worrying about the poisonous effect of big money.

C.D. - Are you talking about the Holland Cotter article that just came out?

D.H. - I saw it, and it seems like he’s chiming in with a huge chorus of people with the same feelings. Dealers are complaining about the situation. Even the beneficiaries-successful artists-aren’t sure what it means. But you know this, as someone who works in an MFA program, that there are young artists rolling out every year. They’re finding their way and self-organizing; they are experiencing the excitement of new possibilities that is a little harder for us veterans to feel. But I still feel that in the studio for sure.

C.D. - That gives me an opportunity to talk about your role as a mentor for young artists. I’m especially interested in what you have to say because I believe I’ve heard that you embrace the ‘artist as charlatan’ model. So what happens when the charlatan comes to student critiques?

D.H. - (laughs)

C.D. - I’m curious about when you’re looking at student work in a highly regarded studio program. What it is that you do to give guidance? Because on the one hand the critique situation can feel like a therapy session in which you listen to the young artist then ask strategic questions to pull them out towards solutions.

D.H. - That’s part of it.

C.D. - …But on the other hand, the critique can sometimes feel like an auto mechanic’s shop where students wheel their work in and your job is to see what will make the engine run a little faster. There’s something diagnostic in both versions, whether you’re diagnosing the artist or the work.

D.H. - For a tune-up?

C.D. - Exactly.

D.H. - It’s complicated because there are so many different roles you can inhabit in the critique situation. To go back to the charlatan issue, the values and criteria for assessing artwork are all constructed-they’re just made up! And that’s part of their mad radicality, that you could rethink everything differently. So what counts as rigor is up to be questioned. I like to think of the critique setting as a complicated conversation in which you try to establish some sort of perspective, or set of perspectives, under which a criterion for evaluating what we’re looking at can be constructed. Sometimes young artists have a set of instincts or appetites for what they’re doing, but they don’t really have a sense of context within history, culture, or even their own lives. So the conversation is a way to move through those positions and to see what sorts of values emerge. Now, of course, in the end it could just be a tune-up or some technical advice. But hopefully the faculty person is also being adjusted in their perspective by the new work in front of them. This happens even if the artworks in front of them are exactly like some other historical works. It’s actually not the same because it’s being made by this person here and now. This constantly adjusts the ability to evaluate.

C.D. - Can you go on with that thought?

D.H. - I’m very wary in critiques, and one of the things I like talking about in students’ studios is the very emphatic judgements made by my colleagues, who might walk in and say, ‘This is total bullshit’ or ‘This doesn’t make any sense’ or ‘This is not very significant.’ So oftentimes there will be an attempt to understand those judgements and put them into context to see what their merits are. Maybe there are merits, but let’s not just accept them.

C.D. - I’m already trying to imagine, probably correctly, which of your colleagues made those comments. But I am glad to hear your thoughts on critiques because the goal is improvement, right? The students are there to improve, and your job is to improve them.

D.H. - Yes, that is the goal.

C.D. - But do you ever feel like young artists want you to write some kind of prescription for them, to make their work better?

D.H. - Yeah, they’ll say, ‘Tell me the truth! What do I need?’ More often I’ll come in and take a look around at all the work–even the little drawings, the scraps of things, the stuff on the floor–and try to measure where the heat is and try to blow air on those embers.

C.D. - That’s a beautiful way to phrase it.

D.H. - Thanks.

C.D. - I was wondering if you had an opinion about the recent trend of so-called ‘provisional’ or ‘casualist’ painting? You know who I’m talking about.

D.H. - Can we call it ‘crap-straction?’

C.D. - If that’s the term you prefer.

D.H. - I know what you’re talking about, and I haven’t really thought about it that much. I think it’s a challenge critically because part of the ambition of casualism is to defy, or shirk off, critical perspectives. It resists language. It’s painting as behavior. The result is often a greater acuteness that solicits an awareness of the nuances of the materials, even though the work was made in haste or has the effect of not caring-perhaps revitalizing ‘not caring’ as a critical posture or attitude. But in the best cases the result draws attention to every scrappy detail or the nuances of carelessness.

C.D. - I think it reorients the compass towards indexical effects-the stains, the scuffs, the tears or the drips. But in the right hands it’s still gorgeous. I really loved the recent Richard Aldrich show, for instance.

D.H. - At Bertolami?

C.D. - That’s the one. I was impressed by Aldrich’s assuredness while maintaining a lightness of touch.

D.H. - It seems there’s one side of his work that’s attempting an historic commentary. It’s built on the assumption that the historic teleologies, or the development of painterly languages, is exhausted. And yet there’s an impulse to revisit them. I think that Aldrich’s work includes within it a kind of reflexivity, thinking about the condition of art, or perhaps other art. But I do like the idea of painting as behavior, that it’s a form of acting that sanctions different styles or methods. But maybe at its worst the new casualism is a form of narcissistic decisionism. The painting is evidence of a series of decisions that were made, and that’s it. I decided this and then that; thus I willed it.

C.D. - And these decisions are under no pressure to form a coherent whole.

D.H. - Right. No grand claims. It’s just the exercise of absurd will.

C.D. - That does suggest a type of selfhood that defines itself as a series of unrelated chance occurrences that accumulate into nothing.

D.H. - Right, and wouldn’t it be ridiculous to claim anything grander than that?

C.D. - Well now that you said that, I suddenly feel liberated.

D.H. - But maybe provisional art is also a response to the overly slick, commodity-obsessed artwork that we see a lot of too. It probably had a running start with the slacker aesthetic and the abject art movement of the ’90s.

C.D. - Are you still going to the life drawing sessions at Will Cotton’s studio?

D.H. - Yes, whenever he calls the troops I’m there. It’s turned out to be a very lovely component of my studio practice. It’s a little like going to the gym, but I’ve also developed a way to go to the sessions with prepared abstract grounds onto which I try to integrate my observational drawing of the figure. It’s kind of a game structure or a self-collaboration. The process has opened up some new ways of making paintings.

C.D. - I have one last question for you. What’s your ongoing connection to Georgia? I know you’ve had gallery shows in Atlanta and you were a visiting artist at the University of Georgia. And you’ve shown and lectured at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, which is where you signed my copy of Blind Handshake-thank you very much for that. How did this happen?

D.H. - It’s random. I will give the credit entirely to Nancy Solomon of Solomon Projects. She became aware of my work sometime in the 1990s, and we did a little courtship in the form of a group show and then finally a solo show in the later part of the 1990s. I think I might have had four solo shows with her. That increased my visibility to the people at the University of Georgia in Athens who asked me to be the Lamar Dodd chair for a semester, where I lived, worked, had an exhibition and taught. Nancy closed her gallery, and now I’m going to do a show at Marcia Wood Gallery in Atlanta. I’ve come to love Georgia. I have an old friend, Robert Spano, who’s the music director of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, so I feel very entangled into the place. But it was completely random. I’m a Yankee.

C.D. - I see that about you. (both laugh) It’s just a description. I remember when you gave your talk at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center you had a full house of loyal fans, like you were a local artist hero.

D.H. - It was great there.

C.D. - So when is your show at Marcia Wood Gallery in Atlanta? Soon?

D.H. - February. I’ll be showing new work, and we’ll see how it goes. The current show at Protocol in Gainesville happened because of the director, Chase Westfall, who was one of my students at UGA, so there’s another Georgia connection. It keeps flowing.

Craig Drennen is an artist based in Atlanta, where he is a professor at Georgia State University. His work has been reviewed in Artforum, Art in America and The New York Times. He served as dean of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and is on the board of Art Papers. He has worked at the Guggenheim Museum, The Jewish Museum and the International Center of Photography.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.