« Features

Beyond Postmodernism. Putting a Face on Metamodernism Without the Easy Clichés

By Stephen Knudsen

I will admit, as academia clamors to find some term for “whatever-we-call-coming-after” postmodernism, I long for the days of yore when the nomenclature took little effort. Often, names came as easy as quips: Malevich meant no compliment when he easily coined “construction art” to describe the work of Alexander Rodchenko. Then with just a little more effort by those more sympathetic, the term morphed into “constructivism.” And we all know how “Impressionism” was born out of a quick critique of Monet’s little painting Impression Sunrise. Stories like these could fill a book.

Now to get more current, the opening salvo of post-po-mo circa 1993 is arguably David Foster Wallace’s E Unibus Pluram-a great essay on sensing a cultural sea change, or at least the need for one. Wallace suggested that perhaps what had made postmodernism vital-such as irony, appropriation and obsessive intertextuality-was beginning to fizzle. The suggestion was radical at that time. Wallace’s exquisite prose, his novel Infinite Jest being no exception, pointed to a return to some form of genuine selfhood and authentic, sincere point of view, an attempt to create something on its own right, and what he famously called “single-entendre principles.” Though Wallace’s voice should not be missed in this discussion, one must, however, look elsewhere for fully developed manifestos or sensible new nomenclature identifying the mood change.1

As for the hideous term post-postmodernism, let’s pray that it is simply a place marker. Nicolas Bourriaud’s essay, Altermodernism, shows some good sense, but unfortunately the term “altermodernism” sounds too much like postmodernism.2

I am trying to gain a fondness for the term “metamodernism,” advanced in 2010 by Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker in the Journal of Aesthetics & Culture.3 The theorists use “meta” as a prefix to refer to “between.” Granted, “meta” is more commonnly associated with the idea of “after” or “post,” but that definition would be unhelpful as we have been there and done that. Fortunately, “meta” also can refer to an oscillation between adjacent positions. Organic chemistry adopted that meaning in its use of “meta” to refer to the occupation of two possible positions, such as the “meta positioning” in the meta benzene ring.

In loosely analogous fashion, metamodernism then denotes the to-and-fro occupation of both the positions of modern attachment and postmodern detachment. (More on that later.)

Now, I hope the reader will forgive me as I reminisce my way gradually into this topic of metamodernism as a way to set the context. The late Stephen Max Myers was one of my best mentors decades ago. He was an actor turned art historian and was fond of using a couple of boat paintings to initiate freshmen into some simple thoughts on modernism and postmodernism. Myers used The Raft of the Medusa and The Old Man‘s Boat and the Old Man‘s Dog to put a simple face on complex theory, and for that we were grateful. The images were helpful, as some of us went on later to challenge our gray matter with some of the most difficult readings in the pantheon of postmodernism-Derrida for starters.

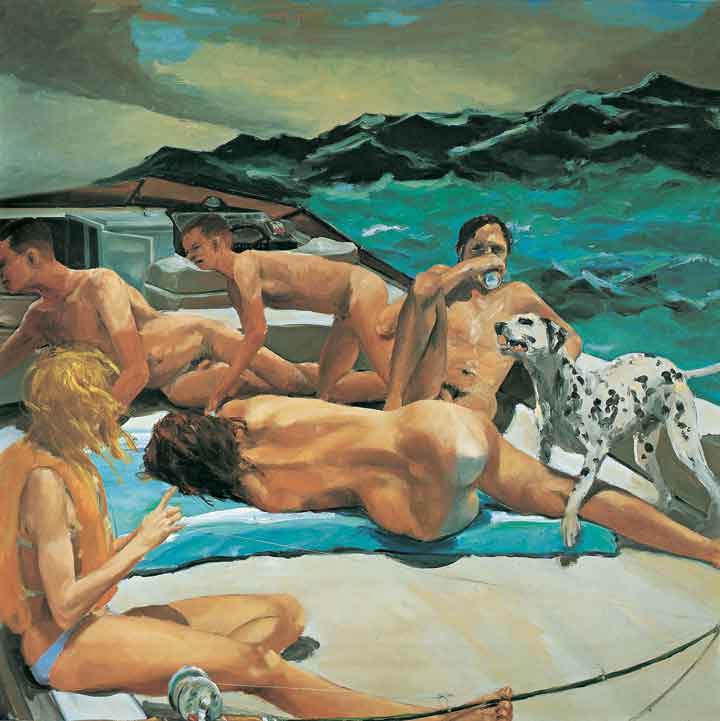

Myers presented The Raft of Medusa as the premium emblem of modernity, and it mattered not in the slightest that Gericault was more modernism’s premonition than its threshold, at least concerning painting. Myers kept the backstory sparse. It was a survey class, after all. I had plenty of time years later to read the survivor’s manuscript, a full account of the tragedy. It was then that I learned the names of the characters-villains and heroes alike. I would eventually learn of Captain Hugues Duroy de Chaumerey-the dandy cluck with almost no experience at sea who was a friend of Louis XVIII’s monarchy. Look what a mess monarchy gets us into. Pre-modern government can be a bummer. In The Raft of the Medusa, Myers saw brave ranks rising up into a utopia of being alive, of finding the best way of surviving. The image spoke of reaching for enlightenment, democracy, the scientific method, egalitarianism and all the modern ideals humans had evolved to possess. In contrast, Myers noted that Eric Fischls’ The Old Man‘s Boat and the Old Man‘s Dog reeked of postmodern apathy.

Eric Fischl, The Old Man’s Boat and the Old Man’s Dog, 1981, oil on canvas, 84 x 84.” Courtesy of the artist.

We know that postmodernism, in simple terms, has been a detachment from modernism. We detached from the Constructivist’s utopias; we detached from the Expressionist’s catharsis; we detached from the Ruskin utopia of artistic moral influence. We detached from the Dada purges. We detached from the Greenbergian truth. We detached from the almighty metanarrative. Postmodernity detached us from believing that our intelligence will keep us from a return to primordial ooze. It detached us from believing that human invention of the end of the world does not have to end the world.

Lyotard, the greatest writer about the postmodern condition-and one not to be missed-kindly pointed out that if we do not vaporize ourselves with our own fission and fusion, the natural fusion will do it as the sun expands just before it burns out.4 We have even detached from Suprematism’s solution to this sun’s expiration date. Malevich explained that we would one day evolve into pure energy. Imagine the new sun we might find traveling at 186,000 miles per second. (Round that up to 187,000 if you are an optimist.)

We detached from modernism like Apollo 11 detaching from its spent fuel. But did we truly? My great suspicion is that Modernism still fuels us. Not like it did before, for sure. E=mc2 in 1905 is not the same E=mc2 in 1945 or today. In 1905, it was an elegant demonstration of human intellect. Today, it is the sublime accouterment to thermonuclear theory and practice that wants to undo us if we make one wrong move.

We find utopian ideas of modernism to be suspect-that is the postmodernism I see. But in practice, there is much of modernism that the world cannot detach from. We have been displeased but not to the point of utter detachment. The kind of postmodernism I see now does not need to exacerbate our angst with hyperbole. It no longer needs to make requisite the air quotes of ironic detachment on words like faith and action. It can still lead somewhere meaningful and concrete. I do not think I am alone here. I know I am not alone as others take similar thoughts into the fray to find some better nomenclature in this late phase of postmodernism.

Concerning The Raft of the Medusa and The Old Man‘s Boat and the Old Man‘s Dog as emblems of modernism and postmodernism, respectively, I sense a third image is needed to add a face to metamodernism. And, of course, with my bias as a painter, I want this image to be a painting. However, finding such a thing is tough, especially with postmodernism’s so-called prejudicial wrath towards painting with a sincere message. Before Robert Hughes passed away this past August, he left us with a lament that so much of art today aspires to the condition of “Muzak.” He said it “provides the background hum for power.” On the other hand, he also said great art “can close the gap between you and everything that is not you and in this way pass from feeling to meaning.”(Hughes 111). The latter, at least, gives us a goal.

I have not found a perfect painting to expand my mentor’s grouping of two boat paintings into a trinity. And I am under no delusions that finding one will import any kind of humanity into our inhumanity. But I do think such an image might be a way to begin to picture some of the complexities of metamodernity.

Alfredo Jaar, May 1, 2011, mixed media installation at SCAD Museum of Art, 2011. Photo: John McKinnon. Courtesy of SCAD Museum of Art and the artist.

It seems to me that this work would need some Goyaesque scope. Today, the Goyas are usually not painters but new media artists. For example, Alfredo Jaar’s work confronting the Rwandan genocide and his Goyaesque Third of May (actually titled May 1, 2011) come to mind. The latter is a commentary on the most powerful situation room in the world the day Osama Bin Laden was killed. Jaar’s full body of work is one of the premier examples of work that engages the metamodern tenet that any kind of information-not just scientific information-can lead to knowledge, and the artistic endeavor is no exception.

However, this work does not provide the enduring archetypal iconography that I am after in my search for a pictorial image, so I will look elsewhere.

Writing projects keep me moving through the major art centers, but I like the artistic backwaters as well, and in 2011 I saw Bo Bartlett’s return to his hometown of Columbus, Georgia, with 123 paintings and drawings shown concurrently in three galleries across town.5

Bartlett lives and paints on an island off the coast of Maine in the summer and on an island in Puget Sound in Washington through the winter and is more known for his last 10 shows in Chelsea in New York City at the PPOW gallery. But the hometown hero makes a point to get home occasionally. The most remarkable show, titled “Paintings of Home” at the Illges Gallery, was chiefly composed of paintings that Bartlett made since regaining his sight after a brief bout with blindness caused by a pituitary tumor in 2008.

A little portrait gave the exhibit a mind’s eye. Blind Tom (2010) is a portrait of Thomas Wiggins, a blind savant born into slavery near Columbus, Georgia in 1849. The definitive 2009 biography by Deirdre O’Connell chronicles the life of Tom-a barely communicative genius who taught himself piano and composed his first tune by age five. At his height, he was one of the most popular American touring pianists, earning the equivalent of $1.5 million per year in today’s dollars and amassing a fortune for his caretaker as an indentured servant. Thomas is the miracle that hailed from Bartlett’s hometown, the patron saint of both possibility and impossibility. The painting is an homage to Tom, but it also marks the time of Bartlett’s own bout with blindness.

Bartlett, himself, has pointed out that brief seclusion in total darkness can help an artist to see better, and this temporary loss of sight opened up his eyes to what the gallery noted as a “new rigor and truth.”

I am inclined to believe this statement because one of the post-tumor paintings, School of the Americas, brought me out of my mild appreciation of Bartlett into a new, more enthusiastic understanding.

Few would question the virtues of Bartlett’s technical talent, which echoes Andrew Wyeth, Winslow Homer and Edward Hopper. Over Bartlett’s long career, critics have also appreciated his attachment to an American painting lineage that goes back to John Singleton Copley or Benjamin West, but he has taken some hard knocks from critics concerning his Wyeth-like sincerity in content.6 For much of the past quarter century, it could be argued that irony and a self-parodying streak have largely sustained narrative painting against postmodern angst about the viability of narrative painting. Why should Bartlett step out from that umbrella and expect appreciation? The answer to that is simple and comes from Bartlett himself. He is happy refraining from such parody, stating, “I am what I am.”7 That said, to call his work devoid of any postmodern orientation is going too far, especially considering School of the Americas. This painting may have the sharper edge that some of his critics were longing for, but still to my eye it maintains a modern sincerity as well.

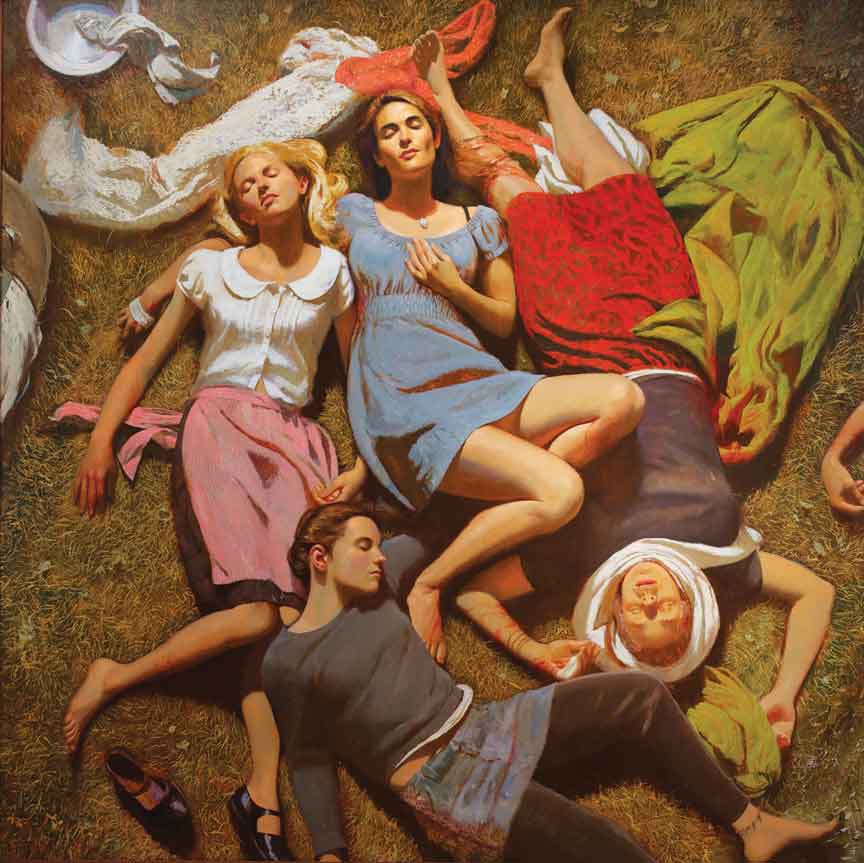

Compositionally, School of the Americas is not characteristic of a typical Bartlett painting. At first glance, one perceives beautiful young women sleeping, as if being observed from a bird’s-eye view. The ring of figures composed on the square panel creates negative shapes that are as complex as the figural shapes. This democratic surface design, like the illusion, is seductive and supports the initial reading. As one moves closer to the painting, however, the initial perception of innocent calm changes as blood and bandages subtly become recognizable. This perceptual shift not only makes us reanalyze the painting visually but causes an intellectual shift to new questions. Eventually, it is evident that the women are either dead or acting dead, but why?

Speak with just about any Columbus resident, and the answer becomes clear. The painting is titled after the controversial training center for foreign military leaders at Fort Benning, Georgia, long known simply as the “SOA” for “School of the Americas.” (Never mind that the United States Army training center has changed its name to the awkward Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation.) Every November, “die-in” protesters seeking to shut down the school don bandages and fake blood and drop to the ground at the gates of Fort Benning as a memorial to those victimized by SOA graduates. The 1980 rape and murder of four U.S. Catholic nuns in El Salvador is one example of such victimization. (Studio sources indicate that Bartlett, himself, has attended eight of the Fort Benning die-in memorials over the years.) The painting’s subject is regional in context but global in scope, raising questions concerning U.S. military reach in the world.

School of the Americas has postmodern reflection on a par with the likes of Eric Fischl, who deftly demonstrated his best with works like The Old Man‘s Boat and the Old Man‘s Dog back in 1981. In the Fischl painting, there is an outright surrender of any hope of a modern utopia, and five reclining figures on a boat couldn’t care less about the oncoming dangers of the storm, a force emblematic of a global dystopia.

Bartlett’s figures in School of the Americas deal with the oncoming world threat differently. As young protesters, they also find utopian ideals to be suspect; however, in their repose they are ironically taking action against the threat. They are confronting the inventors of the end of the world: us. Specifically, they are facing down the strongest military in the world-a military mandated to prevent apocalypse, but also one with apocalyptic potential that could explode if not regulated by the people. School of the Americas becomes a reflection of ourselves; we still want to believe in something good, even in a world with utopian enthusiasm put into checkmate.

In School of the Americas, the figures seem just as paralyzed as those in The Old Man‘s Boat, but ironically, they are just as active in facing a threat as those in The Raft of the Medusa. They do care. There is postmodern angst for sure but not postmodern apathy.

Certainly, School of Americas and metamodernism in general do not mark the return to old-fashioned identity. Rather, metamodernism allows the possiblity of staying sympathetic to the poststructuralist deconstruction of subjectivity and the self-Lyotard’s teasing of everything into intertextual fragments-and yet it still encourages genuine protagonists and creators and the recouping of some of modernism’s virtues.

On some important level, the figures in School of the Americas share more with the figures in a painting like Picasso’s The Saltimbanques than with the figures in The Old Man‘s Boat and The Old Man‘s Dog. Picasso has placed himself and his friends in the role of circus performers. His lover, Fernande Olivier, is seated, and Picasso as harlequin stands next to Apollinaire as strongman. The National Gallery in Washington, D.C., has advanced the hypothesis that this is about an episode of great angst, when Olivier decided to send the little orphan who had been a part of the group’s life back to the orphanage. In School of the Americas, Bartlett also includes his inner circle of friends with his wife, Betsy Eby, at center. In both the Bartlett and the Picasso, loved ones shift as subjects, sunken deep in thoughts of the way out in an angst-drama. This is the modern sincerity in both paintings. We are protectorates of loved ones, and this is the real reason we cannot truly detach from most modern ideals unless, of course, forced to, but I suspect it will be a fight to the death.

And thus, with School of the Americas, at the very least, I have stumbled onto a place marker that puts a face (or at least one facet) on a so-called metamodernism, and there it is in plain view: faith and action without the air quotes and couched in postmodernism’s shadow.

As a point of clarification, I am not suggesting that all postmodern insurgency is vanishing any time soon, as untempered anarchism, nihilism, irony, deconstruction and a dozen other mainstays will still keep a pulse as we attempt to populate infinitely on a finite planet. Pluralism is here to stay, and it is foolhardy to suggest that there will never be a major museum again sympathetic to an artist like Scott Burton, who was allowed to make a spectacle of dismantling Brancusi sculptures to display the pedestals as art (circa 1989). On the other hand, widespread backing away from such postmodern over-boiling is just as inevitable, and if Wallace is right, sincere work, owing only to itself, might just fashion “the next real rebels.”

I am still in denial that Robert Hughes is no longer with us. So I ask your pardon to invoke him one more time as a way to conclude. Hughes, in the Shock of the New, reminds readers of the following: “What has our culture lost in 1980 that the avant-garde had in 1890? Ebullience, idealism, confidence, the belief that there was plenty of territory to explore, and above all the sense that art, in the most disinterested and noble way, could find the necessary metaphors by which a radically changing culture could be explained to its inhabitants.”(Hughes 9). That said, I have to believe that Mr. Hughes also had a notion that all this was not completely lost or at least not lost for good. What else could have sustained him as he put his crosshairs on the art that had become what he called “a cruddy game for the self-aggrandizement of the rich and ignorant”?8 The question now is what is the state of those lovely attributes of 1890 as we dash on towards 2090? I have my fingers crossed for the best.9

WORKS CITED

Hughes, Robert, Shock of the New. New York: Knopf. Rev Sub edition, August 13, 1991.

NOTES

1. Wallace was a harbinger in the after-postmodernism question in a way that is analogous to those writers of the after-modernism question of the late ’60s and early ’70s. Such writers could tell that modernism had stopped “working” properly, but nobody knew precisely what was next (eg.. Rosalind Krauss’s 1972 essay, A View of Modernism) Note: This section on Wallace owes a great debt to my colleague and collaborator Jason Hoelscher.

2. Another recommended reading germaine to the topic is Raoul Eshelman‘s essay, “Performatism in Art,” Anthropoetics 13, no. 3 Fall 2007 / Winter 2008.

3. Vermeulen, Timotheus, and Robin van den Akker. “Notes on Metamodernism,” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture, Vol. 2, 2010.

<http://aestheticsandculture.net/index.php/jac/article/view/5677/6304>

4. See, Lyotard, Jean-François. The Inhuman: Essays on Time. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington and Rachel Bowlby. Standford: Stanford University Press, 1991, pp 11-19 . (paraphrasing mine)

5. The three concurrent exhibitions ran from March 24 to April 23, 2011: “Paintings of Home” at Columbus State University’s Illges Gallery (gallery director: Hannah Israel), “A Survey of Paintings” at the W.C. Bradley Co. Museum, and “Sketchbooks, Journals and Studies” at the Columbus Bank &Trust. The artist curated all exhibits.

6. Joe Hill, “Bo Bartlett,” Art in America January 2003: 105-106. Hill stated that Bartlett’s work was “entirely devoid of postmodern irony.”

7. Quoted in exhibition wall text, Bo Bartlett: A Survey of Paintings, W.C. Bradley Co. Museum, Columbus, Georgia.

8. Hughes, Robert, The Mona Lisa Curse, 2008, (documentary film). Hughes in this remark is referring to the work by a 21st-century celebrity artist who I will leave unidentified.

9. Some of the Bo Bartlett remarks in this essay overlap with my Bo Bartlett review in 2012 issue of the SECAC Review Journal, Vol. XVI, No. 2. Also, this essay draws from my lectures on this topic, the most recent being the 2012 TRAC conference in Ventura, California.

Stephen Knudsen is a professor of painting at Savannah College of Art and Design who exhibits his work in major art centers throughout the United States and Europe. He is a contributing editor and art critic for ARTPULSE and a contributing writer for NY Arts, Hyperallergic, The SECAC Review Journal and theartstory.org. He is also the senior editor of the anthology The ART Of Critique, which will be published in 2013.

[...] 14 Stephen Knudsen, in a brilliantly written and illustrated article, expresses a preference for metamodernism to ‘the hideous term post-postmodernism, let’s pray that it is simply a place marker’. ( ‘Beyond postmodernism. Putting a face on metamodernism without the easy clichés’, Artpulse Magazine 2013) [...]