« Features

Marcus Dunn: Other Youth

SCAD Museum of Art - Savannah, GA.

By Stephen Knudsen

“Other Youth“ is artist Marcus Dunn’s first solo museum exhibition. The paintings portray a dark chapter of history in which Indian children were forcibly removed from their families and put into North American government boarding schools-all in an effort to remove the “Other.”

Dunn shares openly that he is a member of the Skaroreh Katenuaka Nation of Tuscarora Indians in North Carolina. His ancestors fought in the 3-year Tuscarora War 300 years ago in an effort to counter a deadly European incursion onto Native lands and the capture and enslavement of Indian children. The war ended in 1713 with the massacre of over 950 of the Tuscarora.

One hundred and fifty years later-and thirty years after President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act-an insidious new plan to solve the “Indian problem” was realized. In 1860, Colonel Richard Henry Pratt pioneered the first American boarding school for Indian children, built on the cornerstone of, “Kill the Indian in him and save the man.” Photographs of “reformed” Indian children became effective propaganda to promote robust growth of new Indian boarding schools across the United States and Canada. Marcus Dunn sifts through thousands of these photographs in archives1 (recently made available to the public) to find points of entrance for his paintings. These photographs hold history and human essences that Dunn successfully elevates into paintings that ask us to contemplate a tragic history, to attune our empathy, and to respect and promote diversity.

Colonel Pratt orchestrated the system, used for a century, to strip students of their Indian identities. Children were taken forcibly, and some never saw their parents again. Anything to do with Indian culture was forbidden: native language, song, dance, stories, dress, and hairstyles. Once the students reached adulthood, they were spread throughout North America. Pratt ran the Carlisle Indian Industrial Boarding School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. From 1879 to the year it closed in 1918, nearly 11,000 Indian children were taken from their families and placed at the Carlisle school. Indian boarding schools swelled in number. In fact, by the 1970s there were 500 government-run Indian boarding schools. It was not until 1978, through the Indian Child Welfare Act, that Native American families finally gained legal right to reject their children’s placement in off-reservation schools.2

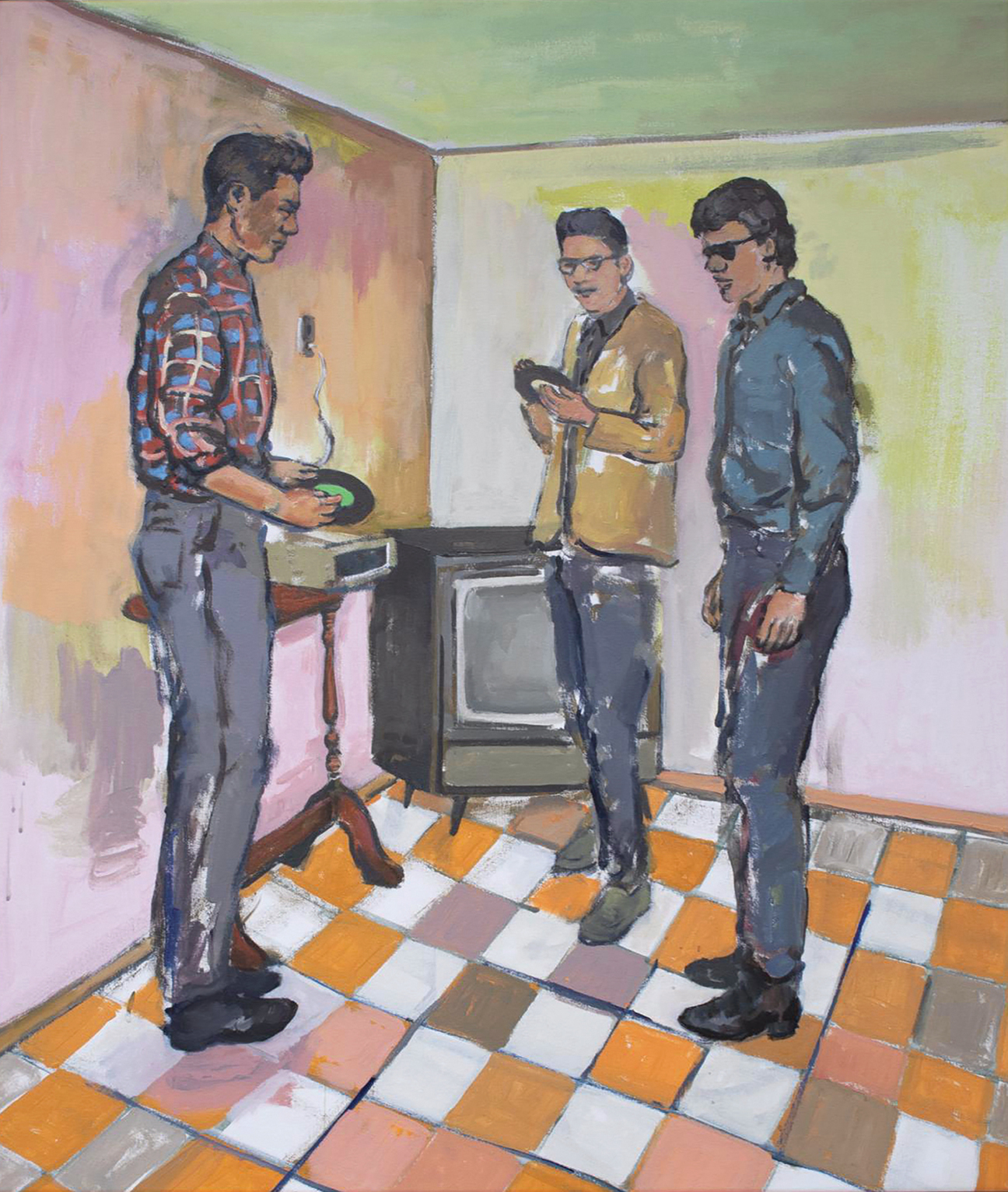

In The Media Room, the irony is not lost. Dunn protracts a scene that was originally used as propaganda of a corrupt system into an indictment of that system. The painting depicts three students in the media room in a 1960s Canadian Indian boarding school. Dunn is not a slave to the photo. However, he is careful to capture the likeness of these Native American students. It is a nod of respect and a contemplation on real victims. Strangely, through robust scrubs of paint and a patchwork of color chords, the walls feel more emotional than the figures, as if the walls contain the stripped souls of these young men. Dunn makes the floor tiles undulate as if they’ve suffered an earthquake-a signifier of losing one’s cultural foundation.

The figure on left holds a 45 RPM speed vinyl record, his gaze not on the record player but on the floor, signifying the reluctant inculcation that resides subtly in the original photograph and amplifies the painting. Dunn accentuates awkwardness by making the hands almost paw-like and the stance a bit more close-legged, stroppy, and stiff. The figure on the right feels this way too. Clearly this is intentional, as the figure in the background middle, the counter point, could not be more at ease, upbeat, and comfortably positioned. The claustrophobic space further presses the theme of ominous external pressure. Dunn has lowered the ceiling and made the walls close in through their warmth and vividness. The TV is the escape hatch. Yes, it is off, but with just a turn of the dial, one could escape. But escape to where? One might take in the Beatles singing, Let it Be, but just as likely take in a Western, so ubiquitous in the 1960s, where Indians were portrayed most often by white actors (like Ed Ames) to be expendable savages.

The most dramatic formal aspect of a Dunn painting is that it has a swift one-pass-of-the-brush feel. Marlene Dumas has referred to this kind of painting in her own work as the act of not killing the painting in a frenzy of overwork. This way of painting leaves holes in objects and figures. It is just enough, and it is the language of something forming and of something disappearing-the primary thesis of this work.

Marcus Dunn’s work asks us to awaken from the nightmares of history with renewed character. Many of us have asked, “how could these atrocities have happened?” But do we ask what is happening now? As I write this, the Trump administration is coming to an end. Whatever your views on that, it is worth visiting the website for the United States Senate committee on Indian Affairs.3 Republican U.S. Senator, John Hoeven (Chairman) and Democrat Senator Tom Udall, and the full committee have made recent advancements on pro-Native American Legislation. One example is the Indian Tribes act of 2019, bipartisan legislation that strengthens tribal self-governance. It was signed into law by president Trump.

To get the balance on the Trump administration’s record on Indian affairs, it is worth comparing Republican press releases on the left side of the home page to the Democratic press releases on the right side.

The Democratic side is quick to point out other major strokes of the pen that were met with litigation from Native American groups. Here is a sample of three:

Top of Form

1. A proclamation issued by President Trump on December 4, 2017, removed over a million acres (80%) from Bears Ears National Monument in Utah. Those lands are now open for oil and gas bidding. Five Native American tribes, including the Hopi Tribe, have filed a federal lawsuit to attempt to reverse the removal.

2. The Trump administration pushed the U.S. Department of Interior to an August 17, 2010 decision to allow sale of oil drilling leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. A coalition of indigenous rights organizations including the Gwich’in Steering Committee has actively opposed such degradation of the refuge. To the Gwich’in people the plain of the refuge is the “sacred place where life begins” and is essential to their way of life.

3. President Trump’s executive order fast-tracked the Dakota Access Pipeline through sacred Indian lands. A lawsuit filed by Cheyenne River Sioux failed to stop construction and the pipeline was completed in April 2017.

In light of what is happening now, Marcus Dunn’s paintings couldn’t be timelier and more relevant. They imply that our good character matters-character that respects the identity of others, character that abides in diversity, and character that makes a place for the uniqueness of the individual, no matter what group we may see him/her in.

Dunn is wisely subtle in the way he makes his paintings carry the photographs’ germ of atrocity. His paintings are aesthetically beautiful and come back to the mind like good songs. Like The Media Room, all the works in the exhibit raise the voltage of the image through a marriage of athletic brushworks to the figure-something 1960’s Bay Area figurative painter, David Park, called the “Sting”.4

There is one painting within Dunn’s oeuvre that is less subtle. Carlisle Pupils was not included in “Other Youth,” but perhaps it should have been since it anchors and clarifies all of his other works. In Carlisle Pupils, Dunn turns the Carlisle Indian Boarding School picture into a gigantic Gustave Courbet-scale painting that stages over 200 children. The children homogenize into one field of gold. At face value, the gold tells the story of subverting the “Other” for land wealth and identity. But as the signifier of wealth and strength, gold delivers this irony as well: To subvert the dignity and identity of the “Other” steals the wealth of possibility from everyone. It weakens us all. It steals something from everyone.

What is most astonishing about Marcus Dunn’s paintings is that they are not angry works, though they easily could have been. Nor are they lamentations. Rather, “Other Youth” honors souls in thought and paint that swiftly tracks over the canvas with kind and empathetic whispers.

(August 20 - November 3, 2019)

Notes

1. The photographic archives used by Dunn: The National Centre of Truth and Reconciliation in Canada, Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections, and U.S. the Library of Congress.

2. Dunn, Marcus, Faces of Assimilation, 2017. Published on the SCAD Library Thesis data base.

3. United States Senate committee on Indian Affairs https://www.indian.senate.gov/

4. Jones, Caroline A. Bay Area Figurative Art 1950-1965, First Edition, December 1989, University of California Press.

Stephen Knudsen is the senior editor of ARTPULSE and an artist and professor of Painting at the Savannah College of Art and Design.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.