« Reviews

Namwon Choi: Blue Distant

Sandler Hudson Gallery - Atlanta, Ga.

By John Rise and Stephen Knudsen

In “Blue Distant” the paintings and objects made by Namwon Choi offer a visual, cultural, and spiritual feast. It is too much for a complete review here, even if we were qualified to remark on the pictorial elements in the paintings that refer to Choi’s South Korean culture. Thus, our review is restricted to the paintings of the landscape within her work, their admirable philosophical and aesthetic intensity, and their place in the lexicon of Western landscape painting.

The landscapes meticulously painted in Choi’s panels are precise, carefully executed and deliberate. They seem to contain anonymous highways extending into the distance, but are in fact site specific. These are paintings of highways in the South-perhaps between Savannah and Atlanta, where Choi lives now and lived before, respectively. The highways are lined with Southern Pines and Live Oaks that conceal the horizon. In that way Choi is a regional landscape painter, as are Wilson Hurley and Woody Gwen in New Mexico. However, while Hurley recorded the grandeur of the Southwestern landscape, Gwen focused on the anonymous highway that split the northern deserts of New Mexico. Hardtop asphalt signifies travel, destination and road trip. But the Choi landscapes of that highway differ from the large-scale Hurley and Gwen paintings. In many of the works Choi has painted tiny, intimate postcard scale paintings (which also connotate road trip) that require close inspection. Many tiny images multiply within larger formats and thus the experience is immersive as well as intimate. The precision and detail of the subjects-the highway guard rails, the needles on the pine trees-these are details that could not be observed from a moving vehicle. Thus, a conundrum-we view the highway from an automobile driving the highway, but that auto must move slowly to observe the particulars of the forest that surrounds the highway. Tree trunks and lower, bare and denuded branches are visible in the bramble beneath the full conifer and oak boughs.

Namwon Choi, Point with Spheres, 2019, acrylic and gouache on 24" diameter canvas and (2) 12" diameter plaster sphere.

Some of the works say something about driving through these pine and pavement moments, minute by minute, hour by hour, mile marker by mile marker. Interstate 16 from Savannah toward Atlanta seems to be on repeat as one mile looks like the next, where banks of ever-present trees flow like an unending river. Choi makes us feel some of that in the painting In Betweenesswhere over fifty, re-presented highway landscape images converge to fit the round format. All is exquisitely detailed and yet the color is simple: monochromatic blue. Complexity and simplicity commingle. Is that not what such a drive is? There is such complexity outside the car and yet with speed, the breeze simplifies things as we zoom through. The monochromatic blue gives these paintings breeze. Then something philosophical is delivered. This beautiful blue planet of roadscapes is positioned into a square made with a simple blue outline on off white. Thus, the blue orb is an eye of the milky way of the square, and beyond the square is the infinity of another universe. The simplicities of life are compounded into complexity. For as we expand into trees on I-16 we are also expanding into a universe, into a mathematical sublime, as Immanuel Kant called it. It is all so simple. It is all so complex.

Choi’s landscape paintings imply time. Just as they required careful and slowed time to paint, they request time from the viewer to closely look, see, and experience the scale of the landscape featured that has been miniaturized into a postcard size format. In that, the painter and the viewer share the experience of looking, recording, seeing.

These paintings stand on their own as landscapes. The small intimacy, the crosshatch technique, and flawless surface invite the viewer into the picture. They extend beyond the conventional paradigm of landscape as small pictures of grand subjects, by multiple repetition across the picture plane. Convention is further subverted by the mono-color palette of cobalt blue sky, treetops, ground, and road, cut into flat shapes that dance across the canvas presented in cubes, flat rectangular panels, and tondos.

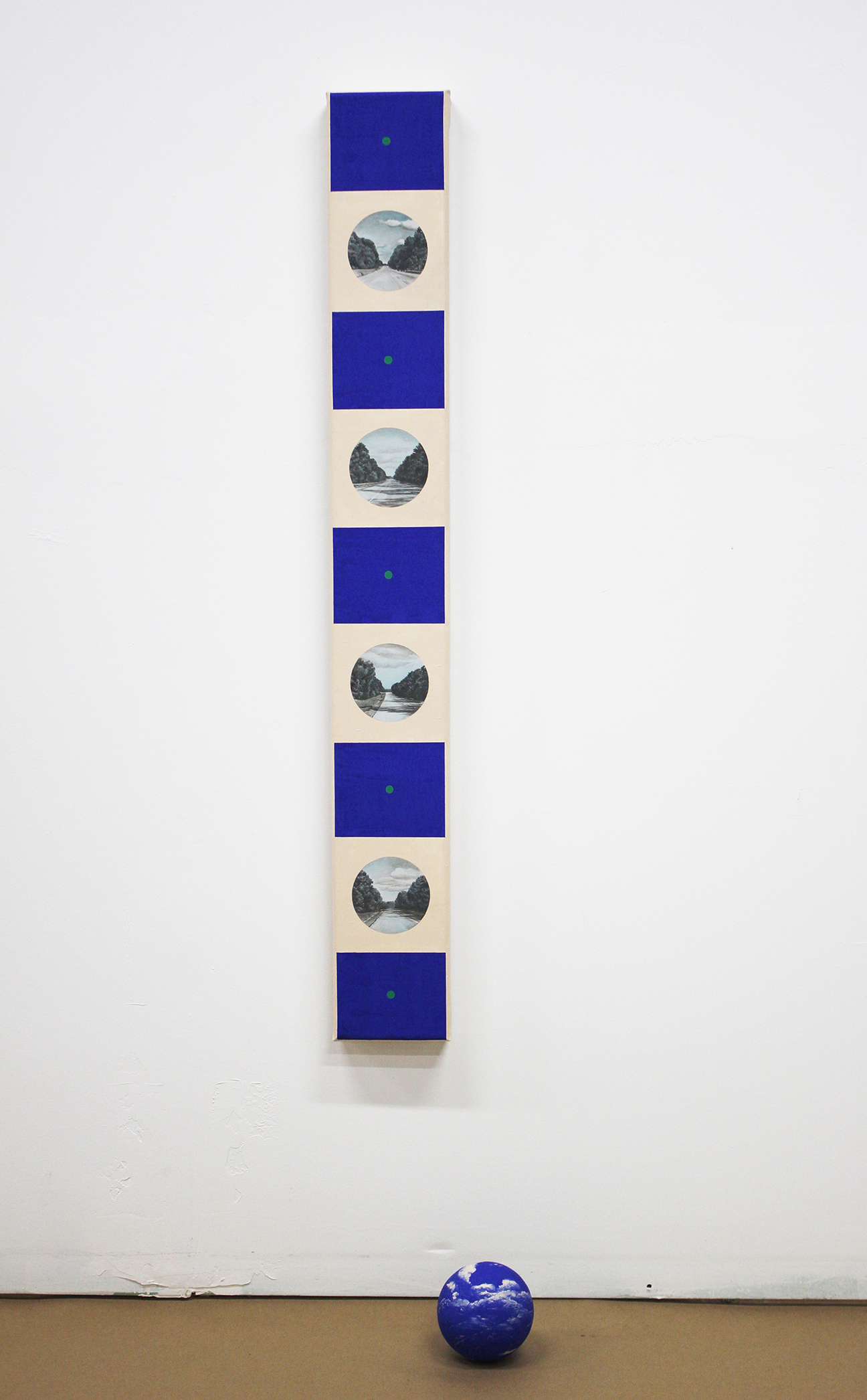

Namwon Choi, Five Points, 2019, acrylic and gouache on 36" x 6" canvas and 5" diameter plaster sphere.

The presentation of the same or closely similar landscape repeated in a composition reminds of the concave multi-mirrored Anish Kapoor pieces that fascinate in public museums. The small mirrors, each mounted on a different angle dictated by the curve of the concave substrate, offer hundreds of slightly varied views of the viewer as we peer into the puzzle of similar self-images. They move as we move, and fascinate in similarity but invite us to look for the slight differences that appear in each reflection. We experience that fascination with Choi’s landscapes. They offer multiple representations of the same/ similar highway bisecting the thickly-treed landscape. They invite inspection and comparison; the intimacy of the scale and technique rewards the viewer for devoting time to the inspection. In that way they channel Rauschenberg’s Factus paintings-two similarly painted constructions that hung back to back, rendering a one to one comparison impossible. Choi offers us the chance to compare without walking around the wall. She puts the “multiples” side by side, or, as inVanishing Points,shelayers the “multiples” top-to-bottom and provokes us to compare. At first glance they feel the same and yet they are not. This captures the sensation and perceptual shifting of a long drive where the landscape seems homogenized, yet not completely, as we zone in and out of it.

In Choi’s Vanishing Pointsa 60″ diameter tondo is the sanctum sanctorumfor the repeating blue landscapes stacked like a layer cake. Strangely, the sky and flanking treebanks in the bottom painting merge into the road of the one above and this repeats in each layer. Driving is merging in and out of realities. On such a drive, especially when one is alone, often the landscape of the mind rises above the landscape beyond the car and then vice versa. Where one becomes truly present, both literally and figuratively, vacillates on such a drive. In this, the title Vanishing Pointrealizes another more philosophical meaning.

It is important to speak to the element of time-why Choi chooses to take the time necessary to make these paintings in gouache. Gouache is a time-consuming medium. Fast drying (even in humid Savannah) makes blended passages difficult and requires layered marks, stipples and cross hatch with a tiny brush-a time-consuming method to be sure. There is a sense of contact the painter engages with the painted surface and subjects that is shared with the viewer. That contact engages mind, eye and hand in a coordinated and, in Choi’s case, a choreographed absorption into the painting. Choi is absorbed in the painting process as we are absorbed in the examination of the painting and painting choices made by her.

Often a viewer will spend only a moment-seconds, really-looking at a painting. Choi invites us to examine her landscapes with scrutiny, to compare images presented side by side-a sort of Find Waldo in fine art experience (certainly a crass comparison). But there is much more than the comparison that entraps the viewer, that makes her work reside in our minds long after looking at her paintings. Perhaps it is a spiritual aspect that exists because it is evident that these paintings, as precise as they are, are paintings, and as such they take time to make. Unlike photography, (albeit these paintings were probably made with photographic reference), which captures an instant in a static image, these paintings offer a different and deeper truth and relationship to the landscape. (The resin-cast tires in the exhibition, cast in white marble dust, speak of/refer to travel, automobile and highway as the only way to experience these vistas). Because they took a protracted time to see and make, there is a sacredness built into these anonymous landscapes. The trees are in different stages of growth and maturity-some are young saplings, others are reaching to the sky for light; older trees flatten at the top, and will soon die. They are impermanent and in transition, made permanent in paint. They are, as Robert Hughes wrote, paintings “that hold time as a vase holds water; art that grows out of modes of perception and making, whose skill and doggedness makes you think and feel; art that isn’t merely sensational, that doesn’t get its message across in seconds, that isn’t falsely iconic; that hooks into something deep-running in our nature.”1

Such are the paintings in Choi’s “Blue Distant.”

(October 25 - November 30, 2019)

Notes

1. Hughes, Robert, Speech delivered to the Royal Academy at the Burlington House, Piccadilly, London; June 2, 2004.

John Rise is a professor in the School of Foundation Studies, Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD).

Stephen Knudsen is professor of Painting at SCAD and the sr. editor atARTPULSE.

Filed Under: Reviews

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.