« Editor's Picks

Collective Utopia: Zenana as the public sphere

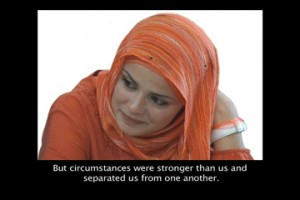

6+: A WOMEN’S ART COLLECTIVE. Turning Our Tongues, 2007. Two channel video. Courtesy of 6+: A WOMEN’S ART COLLECTIVE & Exit Art

“Sultana’s Dream”, evokes an early twentieth century desire in feminism to designate space for women in the public sphere by relegating men to the private, creating a utopist vision expressed as fantasy. Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain inverted the world as she saw it in 1905 British India, effectively altering the lexical marker zenana, a private, female, arguably Muslim culture-specific space, into a shifter with multiple contextual meanings. Zenana no longer indexed a limited space, but expanded to encompass the seen world and demand control over civil society and body/self. Using this story, and the emancipatory desire it expresses, as a point of departure, the artists presented in the tenth anniversary visual arts exhibition of the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective (SAWCC), complicate, extrapolate, and re-appropriate early feminist fantasy as progressive politics in a world post 9-11. These projects emerge through processes that fundamentally alter individual genius into collective invention, employing a spectacular vernacular that, as Stephen Duncombe argues, is necessary to realign power in this society. (1)

A key element in the curatorial vision for this exhibition is the notion of collaboration. Increasingly, in today’s world, artistic interventions for community development and social change rely heavily on collaborative strategies, inclusive processes that allow each individual involved to bring to the table their unique talents, ideas, strengths, and histories. This shift in progressive artistic practice, whereby a collective (such as, SAWCC) requires a process of collaboration to be an integral component of the final product, suggests recognition on the part of contemporary cultural practitioners that forms of aesthetic resistance and political intervention are undergoing profound transformations. This change can be viewed as a choice or a response, dictating new imaginings of utopia.

An altered notion of zenana, from a place where women are collected to a collective where women activate space around themselves, invites new utopias. Begum Rokeya’s zenana may be understood as being both public space and public sphere; the former, a spatial locator, the latter, a space within the civil social governance of the State. Both types of desire to be public indicate forms of utopia that allow women to reclaim agency over themselves, their bodies, and their thoughts, through space and through law.

A journey into the epistemology of utopia reveals mystical and existential elements that unite forms of desires of collective and collaborative process. Utopia, literally ‘no place’, elusive in its specificity of locale, becomes, in a contemporary moment, incredibly illustrative through its articulation of the yearning to possess, exist, and belong. Although collective and collaborative are overlapping concepts, they are not identical. Early examples of collective practice, particularly those challenging the hegemonic order, deployed visions of utopia to encourage and maintain collaborative strategies, the process itself becoming utopist in nature. The use of collective identity, empowering as it may be, obfuscates cultural specificity, gender, and sexuality. However, by erasing indices of the bodies controlled by the State, the collective also becomes the ultimate form of resistance by obscuring discrete identity. Collective identity then becomes paramount, and any value attributed is qualified on the relations among those who maintain it.(2) While these relationships within the collective maintain strength by binding individuals into a whole, a collaborative process recognizes the individual through the active establishment of trust relations to produce a final product. By highlighting this trust, each individual is simultaneously acknowledged as a single actor engaged in the creation of a product that creates and expresses a new conglomerate collaborative identity.

Situating individuals into stereotypes, the media continues to play a critical role in construing reality and constructing images of both the enemy and hero(ine). September 11th, 2001 marked a dramatic shift in these constructions, creating homogenized masses of individuals as collectivities in negative spaces, literally, thus stealing their ability to enter public space, and denying their access to civil society through which they might contest, debate, or express dissent. This is the ugly underbelly of collective identity - the forced stripping of individualism and raping of agency, all in the name of the larger public good of the hegemonic order. (3) Collaboration within that forced collective emerges as a strategy of resistance, reclaiming public space as a necessity for survival. It is this survival that is illustrated in each of the works in this exhibition. As a collective, SAWCC is united by South Asian heritage, as collaboration SAWCC joins the larger community of women in the struggle against patriarchy as embodied by the State. This reclamation of public expression by women transforms the negative and destroyed spaces within which they are positioned and appropriate culturally specific meanings attributed to transgressive action, thereby reassigning signification.

This feminist structural transformation of the public sphere, reorienting zenana through a process of collective utopia, can also be read as entering the Sufi state of haal (a state of transcendent presence). (4) Fariba Alam’s collaborative piece with her mother, Occupied Ascension (2007) refers to that very state by constructing and enclosing space through the limits of repetitive tiles, exploring the tension between spiritual transcendence and corporeal immanence. Utilizing Islamic, Minimalist, and Conceptual techniques of repetition and seriality, this piece reassigns autobiography with transcendental properties, reconstructing history as present in the creation of space. Asma Shikoh’s installation, The Beehive (2006-ongoing), uses similar techniques, capturing space through community autobiography signified by the collection of material, in this case, a hijab. Each cavity holds identity, demonstrating the collective and collaborative strength in a beautiful matrix of form, minimalism, and communal space. Through audience and public engagement, the work has the capacity to penetrate the sociopolitical organization of contemporary life with greater impact and meaning. The site and installation become more than a place of meaning based on disenfranchisement, providing an important conceptual leap in redefining the public role of art and artists. (5)

Creating space within arenas in which space does not exist affords new venues for intervention. The women’s art collective 6+ did precisely this in their project Turning Our Tongues (2006), a collaboration with a group of 18 young women aged 16 -19 from the Deheisheh Refugee Camp, Palestine. Emerging from a refugee camp, bounded in space, limited by force, this collaborative piece explodes out of the discourse of occupation, insisting on documentation of self. Before posting material online, each one of the young women constructs the journals in which they write, articulating their experience as a physical page upon which they transcribe their lives. In a world in which occupation is real in every sense of the word “real,” the Internet becomes a vehicle for intervention transforming the refugee camp from a restrictive plot to a fantastic urban landscape through discursive practice and the access of power it might signify.

Discursive practices, in particular writing, are effective tools for the dismantling of colonial Western myths. In Cyborgs of the world, Unite! Or when a robot decides to call herself South Asian (2007), the collaborators Sreshta Premnath, Jesal Kapadia, and SAFED (South Asian Feminist Educators) in conversation with Ayreen Anastas and the 16beavergroup, situate writing as a major form of contemporary political struggle. This website situates women of color as ‘cyborg identities’ for whom ‘cyborg writing’ is about “the power to survive, not on the basis of original innocence, but on the basis of seizing the tools to mark the world that marked them as other.” (6) The power of appropriating text cannot be underestimated. In the Index of the Disappeared (2003-ongoing), Chitra Ganesh and Mariam Ghani use words, numbers, and names in fragmented suspension, giving visibility to otherwise censored and silenced moments of literal erasure of the other in a post-9-11 world. The locational indexing of dissent is both a visual and emotional marker for the reclamation of public space.

Further sensualizing entrances to space, Ela Shah and Asha Ganpat include architectural elements, interactive light, texture, and scent, in their multimedia interactive installation Pilgrimage (2007). As hybrid sacred spaces, these structures provide phenomenological pathways to transformation in which the viewer is implicated in the activation of change. The significance of the site as location of space can shift from creation to re-creation through destruction. Utilizing teams of remote control robots and army vehicle toys, Carol Pereira alters new miniature spaces created by Yamini Nayar. In this project, the literal configuration of space contests reality of scale, further complicated by the construction of mini-mountains within the real-space of a demolished apartment building in Brooklyn, NY. Ruins Metropolis (2007) signifies the whimsical nature of destruction, controlled remotely and taking place within an already destroyed shell of space.

Remote destruction on remote sites seems removed from the immediate trauma of warfare. Wahida or Lone Woman (2007), a short film by Monira Al Qadiri, is an experience of desolation. Spectacularly framing a single figure against a bombed-out TV station satellite antenna and piercing sunrays, the film reads as a metaphor for the collapse of modernity and socio-cultural structures, including women’s rights, in Post-War Kuwait. The women, veiled and seductively mournful, their eyes bound and mouths gagged, when finally freed, look directly into the camera, challenging and exposing the inactivity of the viewer. Specter (2006), a set of associated photographs by Fatima Al Qadiri play with the notion of veiling and masking, a mask adorned atop of the veil further obscuring the identity of the woman. These playful photographs rely on masquerade to reclaim the female body, suggesting a complete erasure of identity in order to allow for promiscuity within controlled space. Sonali Sridhar and Mouna Andraos’s jewelry employs a similar approach, using adornment to locate oneself within space. The collaborative work Address (2007) consists of necklaces and pendants, each fitted with a global positioning system (GPS), into which coordinates for home are programmed. Once initialized, the pendant displays how many miles away from home the adorned is. This highly innovative and entertaining use of technology in actuality indexes very complex definitions of home, and issues of displacement, dislocation, and loss of community.

In transforming the zenana into a public sphere, is there a sense of loss and dislocation, or a desire to return? These private quarters are quasi-spaces of liminality, with their own rules of social conduct, separated from the civil social machinations of the State. Michel Foucault may have argued for the zenana as a heteropia of sorts based on the presupposition of systems of opening and closing that both isolates those spaces and makes them penetrable. (7) Activating the liminal private space of the zenana, these women artists have revamped the point of origin, revolutionizing the notion of the necessarily inactive and irrelevant zenana to a locale of transformative collective agency through the construction of meaning, space, and publics, and most significantly, through the use of collaboration as a strategy for intervention.

Sultana’s Dream was exhibited at Exit Art, New York from August 4th to September 1st, 2007. The exhibition curated by Jaishri Abichandani commemorated the 10th anniversary of SAWCC (South Asian Women’s Creative Collective)

Uzma Z. Rizvi has been an active cultural producer in NYC over the past five years, including theater, documentary, artist collectives, and radio. She has served on the advisory boards for special exhibits at art institutions such as Queens Museum of Art, and as a Board of Trustees member of Friends of Fulbright India (FFI), where she co-curated the FFI Art Auction. Uzma is completing her PhD in Anthropology/Archaeology from the University of Pennsylvania, is currently teaching at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn in the departments of Social Science, Cultural Studies and Critical and Visual Studies, and is the Faculty Fellow for the initiative on Art, Community Development, and Social Change at the Pratt Center for Community Development.

Published by Wynwood. The Art Magazine. Vol. 1, No. 2, October 2007

Notes

1 Duncombe, Stephen (2007) Dream: Re-imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy. The New Press, NY.

2 ?ufer, Eda (Summer 2007) “Our Cause, Our Art” in ArtForum pp. 113-114.

3 Blake Stimson and Gregory Sholette (2007) in their introductory chapter on periodizing collectivism discuss the two distinctions of collective identity in the edited volume Collectivism After Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination After 1945, University of Minnesota Press, MN.

4 In using the phrase ‘structural transformation of the public sphere’ I am referencing Jurgen Habermas’s work (1991) The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, translated by T. Burger with the assistance of Lawrence (original published in Berlin 1962), Cambridge: The MIT Press., and draw upon earlier notions of self and society as put forward by Hannah Arendt (1958) The Human Condition, Chicago University Press, Chicago.

5 Miwon Kwon (2004) One Place After Another: Site Specific Art and Locational Identity, MIT Press.

6 Donna Haraway (1991) ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’ in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women. Routledge Press; pp.175.

7 M. Foucalt (1967) Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias. From March 1967 Lecture, Des Espace Autres.