« Features

For the Love of Painting. A Conversation with Julie Heffernan

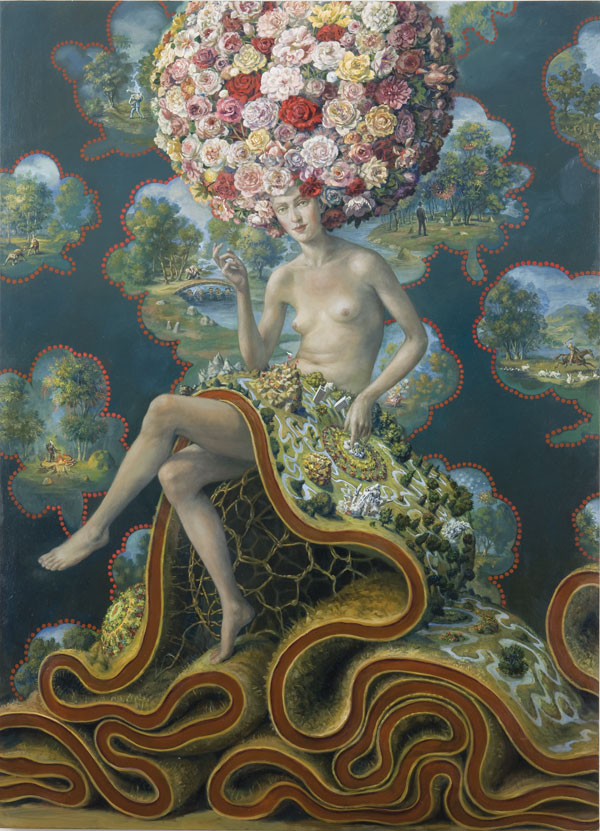

Julie Heffernan’s “image streaming” paintings show that intelligent, relevant and critically aware iconography is alive and well despite the fact that iconography, sadly, has long been a bête noire of postmodern semiotics. Her very personal, even grand paintings deliver Bonnardian multitudes of color and objects while they also recall Renaissance, Mannerist, and Baroque figuration within a distinctly contemporary context.

A traveling retrospective of her work was organized by the University Art Museum, University of Albany, New York in 2006. In 2013, Heffernan had a solo exhibition at the Palo Alto Art Center, which traveled to the Crocker Art Museum later in the year. Her work has gained critical attention in publications including Artforum, Art in America, ARTnews, The New York Times, and ARTPULSE. Raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, she now lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

In this interview we talked about a sex positive attitude and Third Wave feminism as it relates to her work. We also touched on issues of technique and her upcoming solo exhibition at Mark Moore Gallery in LA.

By Stephen Knudsen

Stephen Knudsen - When I look at your paintings the idea of a shameless belief in painting prevails-a belief that would never dream of serving up the self-portrait with postmodern air quotes. In fact, if I could be so brazen to just say it, your painting sits so well on the historical trajectory of great and grand painting that it seems to dare us to just try not to believe. What do you in fact believe?

Julie Heffernan - I love that you use the word “shameless” because one of my big breakthroughs as a young artist involved painting something I knew was embarrassing, possibly ridiculous, but which I wanted to see, to look at it closely and consider that which is outside of myself. In terms of the ego, it’s the dangerous place shame can take us to that often provides good fodder for an artwork. And don’t many of us artists work from a place of needing to see something manifest in the world that we’re either afraid to look at, or need to see because it isn’t here now?

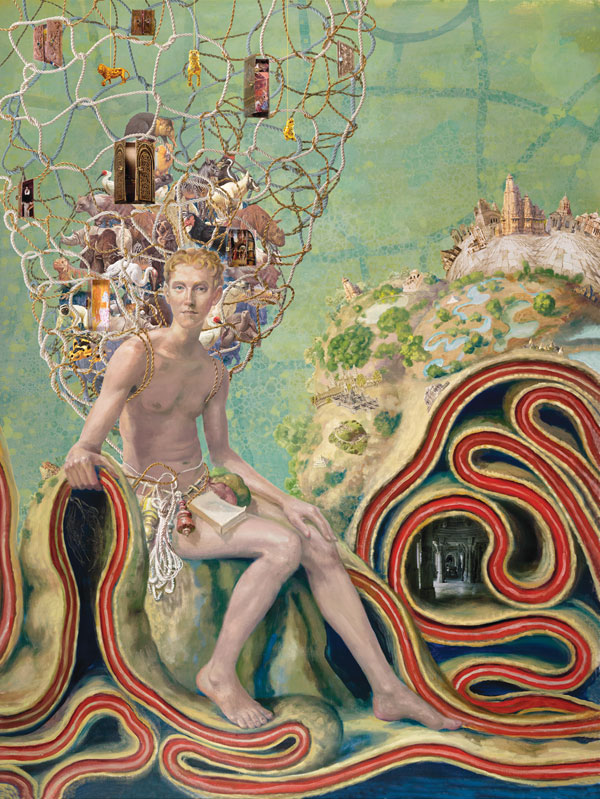

Julie Heffernan, Self- Portrait with Talking Stones, 2011, oil on canvas, 72” x 68.” All images are courtesy of the artist.

As far as what I believe goes, I grew up in a very Catholic home in a dreary East Bay suburb we called Hayweird, and the contrast between the holy cards I lived with at home, depicting radiant saints holding their breasts on a plate, versus the dull mall culture that filled out our weekends was huge; in every way possible I wanted to throw my lot in with those outlier creatures we called saints. So when I came of age artistically in the ironic 1980s, I knew eventually that irony and coolness just weren’t going to work, that they were, for me, simply boring. I did try, living in an Altbau in Kreuzberg, doing huge, thick paintings of rotten teeth, meeting Heiner Müller, putting graffiti on the Berlin Wall, that kind of thing.

But eventually I discovered the world of interior imagery-or image streaming-and imagination won out over antics or theory on its own. Emerson described the difference between the things that we “learn” (tuition) and the truths that we perceive (intuition), and I see intelligent imagination-scrutinized imagination-as the process that brings these two worlds together. Tom Waits, no stranger to the cool, talks openly about begging the song muses to come to his aid when he’s stuck. He knows the importance of humility in the face of trying to create. Working from the imagination in conjunction with a wagonload of things we care about is so much more interesting, and humbling, than just having an idea and illustrating it, which I used to do before I knew anything about image streaming. I have my urgencies–impending environmental collapse is enough to fill a lifetime of canvases–but, filtered through the imagination, those urgencies take on nuances that no screed could have.

S.K. - Would you describe further this phenomenon of “image streaming” and what it means in regard to the “self-portrait,” that term so ever-present in your titles?

J.H. - The interior pictures that flood into my brain when I’m in a relaxed state, or when I’ve been pondering a painting problem for a chunk of time, are the equivalent to me of little miracles, and constitute a road to truth in this sense: if I follow the intuitive prods I get while painting I will inevitably wind up with something that has an integrity to it, a surprise and a jolt. And that confers a kind of wholeness and integrity upon me, in turn. I feel myself getting better and smarter when I work this way, since our brains are constantly growing new neuronal connections in response to fixing our mistakes, and recalculating what we just did in terms of the whole world of the picture, telling us where we’ve gone wrong, where things aren’t hanging together, giving us tiny clues as to what could come next to develop the pattern that is slowly unfolding as we follow along. It’s a way of making our minds visible to a viewer, and I look for that component when I look at any art, the part of it that allows me to see the artist outside of himself or herself, available to me now in a form that crystallizes the self in the fullest sense, exceeding mere intellect. That for me is the essence of the Self-Portrait and why I continue to use that term for most everything I make.

S.K. - To anyone versed in art history your paintings seem familiar and yet paradoxically they seem unfamiliar at the same time. We see the Dutch Golden Age, the High Renaissance’s radiant Venetian color, Leonardo’s tonal unity, and of course the female nude in the acreage. But what would be definitely unfamiliar to the 16th century Venetian would be a Third Wave feminist eroticism that asks not to be objectified but to be empathized with. I see it in the old work like Self Portrait as Mother/Child and the new work as well. Does that make good sense and if so would you unpack that idea in the context of some of your paintings?

J.H. - Feminist eroticism reminds me of Jane Campion’s depiction of Isabel Archer in Portrait of a Lady, where Isabel’s complex interior life is metonymically captured in the sensually swishing folds of her long, elaborate skirt, snaking over the ground like some exquisite swamp thing. Or Fragonard’s The Swing, with all its Rococo ooze, depicting the main female character as a ruckus of swirling pink folds within a quintessentially feminine space, like a fabulous vagina. Feminist eroticism is all over great painters like Titian and Rubens too.

As the figures in Mother/Child took shape I saw that, without my planning it that way, the mother’s and son’s genitalia had merged. The baby is pulling away from her, or maybe she’s pushing him away, but either way the mother and child are both one, and also two distinct bodies at the same time, and that kind of merging within the separateness of individual egos is the kind of thing that Peter Sloterdijk is getting at when he talks about the “biune” or the merging of selves through the medium of intimacy. Empathy is, at its core, imagination, since it involves being able to assume the body of another, feel what it’s feeling. The act of painting itself can sometimes reach that level of intimacy when dense material slips through your hands and falls into the right place on the canvas as though it had a life of its own. Imagination is like a marriage between our outer and inner selves, and is intoxicating to wield because of that intimacy it creates and fosters. And vision itself can have an eros to it: I’ve spoken about the ancient Greek theory of vision where psychopodia, or mind fingers, emerge from the pupil as an effluvium that reaches out and ‘touches’ the object of vision. Isn’t that a gorgeous idea, and so essentially true despite the fact that it’s not? And doesn’t it show such a profound understanding of the intimacy inherent in the gaze?

S.K. - Indeed it does. And by the way I will never look at the Fragonard the same! You know he put the prone male lover down in the rose bed peering up at that “fabulous vagina.” Talk about psychopodia. I wonder, though, if any kind of feminism is subverted because of the male agenda that the contemporary sensibility has become unsympathetic toward (thanks in part to John Berger’s Ways of Seeing.)

J.H. - I think it’s possible to re-think the male gaze in more sympathetic terms too, ways that aren’t quite so much of a scold as in early feminist rants (necessary as those rants were to wake up a generation of men and women stuck in roles that fed neither). Having two sons and a really good husband I’m inclined to view that penetrating male gaze I encountered in my first theory classes in a less pernicious light. With some awareness of the straightening nature of gender roles, I see the root of that gaze lying in a man’s urge to merge with the exquisiteness of the female (read Mother), and that it becomes aberrant only when removed from an empathic understanding that, at its core, is a desire to reenact the experience of the reciprocal gaze of mother and infant. His dearth of imagination is what turns the impulse to adore, to merge faces-a sacred impulse according to Sloterdijk–into a desire to dominate and eradicate a woman’s agency. His longing and a spectral image of the desired one is all that he has left to him, with no appropriate vehicle to contain it, so yes, it goes awry and gets manifest as a will to dominance instead. Laura Mulvey’s essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” theorized something we had simply taken for granted-that Marilyn Monroe just had to be looked at. Mulvey allowed us to see that behind that act was a need to make her subject to our desires, to deactivate her and position her in ways geared to voyeuristic pleasure.

While Titian, Rubens and Bonnard portrayed women at times in compromised situations, I’ve been drawn to their paintings for how much it’s clear to me they did understand about women. So many of their female figures did not primarily exist, to my mind, for anyone’s voyeuristic pleasure, but rather for the access they allowed to a greater depth of women’s experience, as in paintings like Titian’s Mary Magdalene. It tells a story about suffering and how it dis-integrates us, captured in the way Magdalene’s hair transforms into consuming fire. As for Rubens, his female nudes are always depicted as muscular, activated and powerful in their agency, and I always look to them as figures of thrillingly complex emotion. And Bonnard, in so many of his paintings, is not looking at his naked wife in an objectifying way but seeking to engage with her deeper mysteries via objects closely identified with her Otherness, and with the mess and mortar of female experience. I take my cue from those kinds of great artists, to look with empathy and imagine my way into the struggles the women I paint are having.

S.K. - I am appreciating this 21st-century new feminism: making room for the empathetic erotic gaze in our historical interpretations and in the contemporary agenda. And certainly in your own work the empathetic stance-in general-is signified by always titling “Self- Portrait As……” I think your work also displays the sex-positive feminism that emerged in the late hours of the Second Wave and now has so much currency in the Third Wave. In Self -Portrait Talking With Stones we can see the female erotic gaze almost identical to Titian’s Venus of Urbino and here one might wrongly transfer the argument of male-driven oppression-in Titian’s work–to your work. Rather, there is female empowerment in Self- Portrait Talking with Stones. If a thinking contemporary woman wants to publicly show cleavage and an erotic gaze, and other “fabulous” attributes, even in a sincere stereotypical female way, she should be able to do that (or not) without subverting the work done in the first two waves of feminism. Are you being sympathetic to that construct in a painting like Self- Portrait Talking with Stones?

J.H. - In that painting I was determined to use, for the first time, the pose of the semi-reclining female nude (one I had always consciously avoided because of the passivity it confers on her, and how inherently problematic that is) to see if I could activate it and turn it into something that brought life to her instead. I wanted the imagery around her (the burning ship, patient in traction, etc.) to look like it was emerging from parts of her body, as though her body was actually thinking. Really I wanted everything to feel a little bit alive, even the stones themselves that are covered with runes and texts. I wanted everything to look like it was breathing and thinking.

S.K. - How do you see empathy playing out when you paint the males in your life? Self-portrait as Mother/Child depicts your infant son in 1997. You featured a male figure in the 2012 Self- Portrait as Intrepid Scout Leader. Has the child become a man? (There is too much of a familial resemblance there not to be your son).

J.H. - Yes! Those are my sons: Self-Portrait as Mother/Child features Sam, my younger son, and Self-Portrait as Intrepid Scout Leader is my older son Oliver’s body with Ingres’ face (can you recognize him?). The first incarnation of Self-Portrait as Intrepid Scout Leader showed a young man holding a pile of weapons. I’d been listening to NPR during the first days of the Iraq War, and I found myself really irritated by boy-going-off-to-war culture, so I wanted to make a satirical piece about guys and their weapons, the burden of armaments. I remember very clearly my son coming down to the basement (where my studio was) to ask me something unrelated, and glancing at the painting with the boy and all his weapons, and making a little face. I doubt if he even knew he’d done that but I knew nevertheless right at that moment that I wasn’t on the right track. I had been doubting my direction already, but that was the confirmation I needed. If we’re good at reading reactions we can garner clues about whether we’re on to something in our work from the tiniest of expressions in people whose reactions we trust, and Oliver’s response was what I needed to put myself on a new track, and deal with what turned out to be the real subject of the painting: a story about a young man leaving home (Oliver was in fact going off to college), armed with a tool belt (no longer weapons, but books, keys, grigri bags, things he might need to go off into the world) and a backpack holding endangered animals and what I call images of wisdom: copies of those paintings that have taught me important lessons about life, like El Greco’s Fra Paravicino and Breughel’s Tower of Babel.

Julie Heffernan, Self-Portrait as Intrepid Scout Leader, 2012, archival pigment print, museum board, glass jewels, metal fittings, gold leaf, PVA glue, acrylic handwork, 36” x 26.”

S.K. - So what is Ingres’ face doing on your son’s body? Was this in a dream or was it to pay a debt owed to Ingres?

J.H. - It was from the famous self-portrait of Ingres, and I wanted to put that face of an older gentleman on my son’s young body, perhaps to create a symbiosis that might magically confer gentlemanliness on Oliver (although he is already quite a gentleman), to help him age well!

S.K. - I have long been intrigued by your signature landscapes folded and rolled like endoplasmic reticulum in a cell body. What are your thoughts on depicting the ground like this?

J.H. - Coming out of paintings like Self-Portrait as Big World I was imagining a cross section of the earth like a carpet of flayed flesh the figure was sitting on. The carpet is now a section of landscape holding various temples and architectural structures that embody complexity in their form, as well as landscape features. So it was like the world in miniature with folds revealing labyrinthine enclosures and mysterious caves, and grottoes with roots showing on the underside of the earth flesh. I look for forms that can function metonymically, so they can be several things at once. In this case a carpet to sit on, flayed meat, and the earth itself.

S.K. - I have a number of my students suggesting that I ask you about your technical procedures in making a painting. They are ready to follow in your footsteps. Any glazing secrets to share?

J.H. - I only glaze as icing on the cake. Meaning, the paint has to have substantially created form before any nuancing of that form occurs, and glazing is inherently insubstantial. So I try to paint through all the passages with as much direct tactile paint as I can, and then only at the end, when I want to pump something up or push something down, or fade a thing out, do I use glazes. Glazes can be magic or they can be wimpy, so watch out for wimpiness in painting!

S.K. - Speaking of students, and your teaching endeavors at Montclair State University, what is a primary belief that you hold to in teaching painting effectively?

J.H. - To care about my students is my primary belief. They are putting themselves on the line to pursue this crazy life (many of them don’t come from big buck families) and I know how incredibly rewarding an art life can be (if someone gives you some fair warning about the hard knocks), so I want that for them; the world will only get better with more good artists in it, for the right reasons! These students constitute the next generation of art makers and maybe they will bring some sanity to the art world, ease it out of its need to legitimize itself through anti-art self-loathing and a dependence on sophistry masking as scientific legitimacy, obfuscation posing as profundity. The best of them are so smart. They will figure it out!

S.K. - In bringing this to a close would you let us know about your next exhibition?

J.H. - Yes! Mark Moore Gallery in LA opening May 7th-Sam’s birthday!

Stephen Knudsen is the senior editor of ARTPULSE. He is an artist and professor of painting at the Savannah College of Art and Design and a contributing writer to The Huffington Post, Hyperallergic and other publications. He is an active visiting lecturer at universities and museums, and his forthcoming anthology is titled The ART of Critique/Re-imagining Professional Art Criticism and the Art School Critique.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.