« Features

Mona Lisa to Marge: How the World’s Greatest Artworks Entered Popular Culture

“Leather Last Supper” poster of the Folsom Street Fair, an annual BDSM and leather subculture event in San Francisco. Photo: Fred R. McMullen. Courtesy Folsom Street Fair.

Interview with Francesca Bonazzoli and Michele Robecchi

“The 1960s in a way saw a return to the 6th century, when Christian images were celebrated as ‘miraculous’ and were blessed by rituals of all kind.”

On the occasion of the coming publication of Mona Lisa to Marge: How the World’s Greatest Artworks Entered Popular Culture (Prestel), we talked to Italian authors Francesca Bonazzoli and Michele Robecchi. Bonazzoli is an art historian based in Milan and regular contributor to the arts section of the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera. Robecchi is a writer and curator based in London, an editor at Phaidon and a contributing editor to ARTPULSE. We discussed, among others topics, how some artworks become iconic and others don’t, the criteria for determining that, the stories behind some of the works, and the complex relationship between high art and popular culture.

By Paco Barragán

Paco Barragán - How did the book Mona Lisa to Marge: How the World’s Greatest Artworks Entered Popular Culture come about?

Francesca Bonazzoli - People working with images develop a tendency to take them for granted, and we are no exception. One day, we stumbled into a wall painting by Tammam Azzam that reproduced Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss on the façade of a building battered by the bombing in Damascus, and we started questioning the universal value of images and how some of them have the faculty to transcend borders and cultures. We noticed that over the centuries some artworks have acquired a special communicative power, and we asked ourselves why. We wanted to investigate the reasons behind their fortune.

P.B.- The subtitle is How the World’s Greatest Artworks Entered Popular Culture. High art and pop culture have always had a very dialectical relationship, that is to say, the cultured versus the uncultured. Why do you want to swim in troubled waters?

F.B. - The relationship between high and popular culture is not an exclusive contemporary phenomenon. Or, as Walter Benjamin put it, it doesn’t stop with the mass reproduction of images. It’s always been there. Leonardo’s The Last Supper, arguably the first artwork divulgated in a thousand copies through the technique of engraving, has been the favorite target for parodies and manipulations from a legion of restorers, artists and copyists. Bernard Berenson used to despise it precisely because it represented a threat to the elitism of taste perpetuated by popular culture’s habit to claim high models and subsequently trash them. Titian’s version of the Laocoön as a group of three monkeys is a hint to his peers’ mania for collecting and imitating ancient statues. I think it’s interesting to see how, in the long history of images, the dialectic relationship between high and popular culture could determine an artwork’s success.

Michele Robecchi - Perhaps it is the proverbial case of the opposite poles attracting each other. As Francesca pointed out with the example of Titian, quite a few renditions of these images are the work of other artists. Their presence in our culture is so strong that it is possible to be familiar with them without even knowing what they are about. I personally see this book as an etymology exercise as well as a respectful tribute to the artworks in question. By telling their story, we honor their heritage and make a partial attempt to restore the authors’ original intentions.

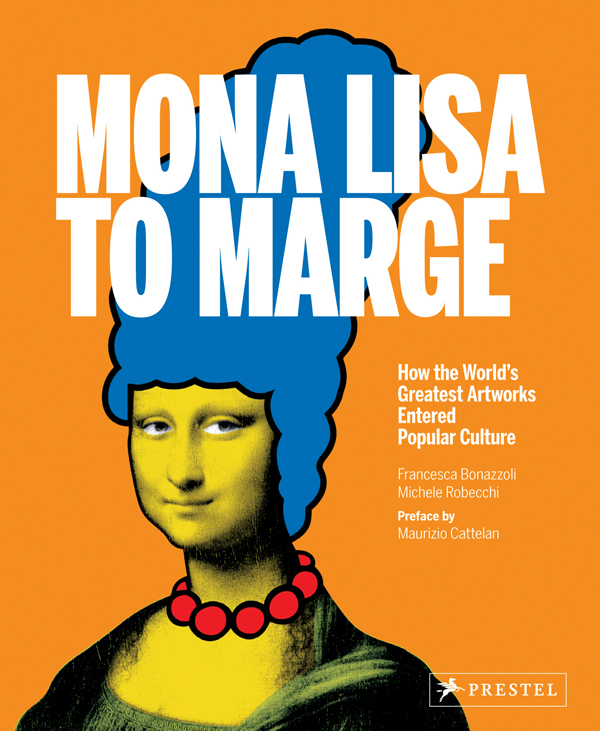

Cover page of Mona Lisa To Marge. How the World’s Greatest Artworks Entered Popular Culture, by Francesca Bonazzoli and Michele Robecchi (Prestel, 2014). Based on Mona Simpson, by Nick Walker, 2006, montage, 27.5” x 19.7.” Courtesy of Nick Walker.

ARTWORKS, ICONS AND MASS MEDIA

P.B. - In the introduction you mention the anecdote of The Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci and the fact that it only enjoyed fame after its theft in 1911. What makes one artwork iconic while others are ignored?

F.B. - This question was also our starting point-what turns an image into an icon? What we realized at the end of the process is that there is no recipe. Every image found its way to fame. There have been thefts, strategic collocations (The Nike of Samothrace), books and films (Girl with the Pearl Earring), accessibility (American Gothic), and so on. At the end of the day, the secret is in their magic. That’s the extra ingredient that triggered the transformation from image to icon.

M.R. - And quite often the determining factors are not even inherent to the art. Every artwork’s rise to immortality is a story unto itself. The stars have to be aligned in a certain way to make it happen.

P.B. - You mention the 1960s as a ‘fundamental moment of success’ in which many of these artworks became icons. I guess that post-modernity and its strategies as well as the advent of Pop Art were also decisive in the consecration and distribution of these ‘objects of veneration?’

F.B. - Yes, that was a fundamental moment, although not the only one, at least from an historical perspective. The proliferation and availability of images after the 1960s boosted their popularity. Semi-forgotten artworks, like Botticelli’s Venus, suddenly became icons, while others, like The Apollo Belvedere, have been ignored. Velázquez’s Las Meninas, which was considered a ‘theology of painting’ since its first outing in the 17th century, consolidated its reputation. The 1960s in a way saw a return to the 6th century, when Christian images were celebrated as ‘miraculous’ and were blessed by rituals of all kinds.

P.B. - Which criteria did you use when selecting these 30 icons, among which there are works like Myron’s Discobolus, Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, Michelangelo’s David, Velázquez’s Las Meninas, Munch’s The Scream and Picasso’s Guernica?

M.R. - They selected themselves. Our initial criteria was limited to register which artworks have joined global cult status and why. This is probably why we only have 30. It’s an exclusive club, and it doesn’t accept new members easily. We didn’t have the ambition of putting together an exhaustive guide to the most important art ever made or to the best 20 artists in the world. It is not one of those stultifying ‘100 artworks you must see before you die’ coffee-table books. We individuated and examined 30 images that emancipated themselves from their original context to the extent of assuming a life on their own. The reasons transcend the intrinsic quality of the images and even the talent or reputation of their creator. Artists like Caravaggio, Cézanne and Rembrandt made a significant number of extraordinary paintings, but none of them quite broke into popular culture. Conversely, we have a regional painter like Grant Wood who hit the jackpot once and never managed to repeat himself with the same degree of success. Historical circumstances play a major role in the reception of an artwork, and they are not foreseeable.

P.B. - Art history is huge, and making a selection always implies leaving out artworks. I’m thinking of Goya’s The Third of May, for example, which served also as inspiration for Manet and Picasso and Chinese artist Yue Minjun. Which master work or works did you finally leave out?

M.R. - It clearly wasn’t an easy process, and we debated extensively over the merit of some pieces over others. Fortunately, the parameters we set at the beginning were so straight that things quite naturally fell into place. One of the fundamental criteria we adopted was to include only art that is unquestionably popular on a real, worldwide scale. Paintings like James McNeill Whistler’s Mother, J.M.W. Turner’s Storm or Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo’s Il Quarto Stato are all iconic artworks in their own right, but not on a truly international level if compared to the ones we have in the book. There are also artists like Keith Haring or Roy Lichtenstein, who developed an iconic language, but for some reason this was never translated into one single, outstandingly successful image.

F.B. - The images we chose are acknowledged and recognized in every corner of the planet, even by non-Western cultures. We discovered from the manufacturer of the inflatable doll of Edward Munch’s The Scream (an artwork originally made in Norway) that the majority of buyers are from America and Japan, and that half of them ignore that there is a painting with the same name, let alone who the author is. The success of The Scream lays in its ability to convey an existential anguish, a contemporary representation of psychological pain as opposed to the physical one pictured by the Laocoön in fashion until the early 1900s.

ABSTRACTION, PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE TIME FACTOR

P.B. - From the list of works we can confirm that except for Mondrian’s The Blue, Yellow and Red Compositions, the selection adheres to the ‘narrative tradition’: figurative artworks. This implies that for an artwork to become an icon it needs to be representational? Also that abstract art can’t comply to mass culture’s narratives?

F.B. - I guess you can empirically demonstrate that that’s the case, although there are many exceptions. Once a sign is manipulated, parodied, reinterpreted or decontextualized, it obviously loses some of its identity if compared to a figurative image. If abstract images have less success in popular culture it is because they have to be taken in their entirety in order to be readable and recognizable. A poster by Miró can be hugely popular, but the symbol of the city of Barcelona composed of three of his signs can hardly be detected as one of his artworks.

M.R. - I think it’s also a temporal factor. Abstract art has been around for 100 years. It’s a relatively recent phenomenon, and even in academic quarters there are still question marks about its legitimate excellence.

Tomoko Nagao, Botticelli—The Birth of Venus with Baci, Esselunga, PSP, and EasyJet, 2012, digital work, ed. 5, 39.4” x 82.7.” Private collection. © Tomoko Nagao.

P.B. - Why did you stop in the 1960s with Warhol’s gold Marilyn Monroe and Margritte’s Son of Man? Have other recent artworks by contemporary artists such as Jeff Koons’ dog (Puppy) and Damien Hirst’s skull (For the Love of God), which has been reproduced ad absurdum, achieved the status of an icon? Is (the passage of) time still a conditio sine qua non for an artwork to be consecrated as an icon?

F.B. - The time factor is again crucial, but not just because time is an insurance policy for greatness. Sometimes the celebration of an artwork goes back and forth with time. Some forgotten artworks unexpectedly resurface and vice versa.

M.R. - The success of the Girl with the Pearl Earring is possibly the best example in this regard. It took almost 400 years, and it happened in the most improbable way, through the film adaption of a speculative novel. Phantom Planet’s spoof of Maurizio Cattelan’s A Perfect Day or Steven Meisel’s fashion shots after Marina Abramović and Ulay’s performances are evidence that contemporary art is not that far behind in terms of being co-opted by popular culture, but it’s objectively too early to tell whether that means that these works have earned the right to sit in the pantheon. Are these images really iconic or just fashionable? Will they be still relevant in 100 years? Popularity, especially in the Internet age, is such a volatile notion. We needed to put some distance between our subjects and us.

P.B. - Most of the artworks selected are mainly paintings and some sculptures. Has photography not entered yet the realm of iconization? Think of Alberto Korda’s portrait of Che Guevara, for example, which has been copied by, among others, Jim Fitzpatrick, Andy Warhol, Gavin Turk, Marc Bijl, Scott King and even by the car company Mercedes-Benz.

F.B. - We decided to exclude photography because otherwise it would have been a different book. The idea of this book is to offer a practical, manageable, ready-to-use survey on the history behind the success of certain images.

M.R. - The problem with photography is that it exists in many different forms. Its inclusion would have introduced a fresh set of issues, including having to define what is art photography and what is not. When we started discussing the book, it didn’t take long to realize that photography was a subject of such magnitude as to deserve special attention. Maybe it will be our next publication.

KITSCH, POST-PRODUCTION AND ART HISTORY

P.B. - Greenberg, but also Marxist theorists and the Frankfurt School, among them and especially Adorno, codified a very simplistic definition of kitsch: practically everything that belonged to the realm of mass and pop culture and allowed for a harmonious, easy and beautiful aesthetic experience that didn’t produce critical consciousness. How do we reframe the concept of kitsch in contemporary society, as most of these images that contribute to the iconization and veneration of a master work fall under this category; think of advertisements, posters, mugs, bags, et al, which have entered fiercely the realm of high art both formally, conceptually and aesthetically (think of Koons and Hirst but also Richter and his big, flashy, abstract paintings)?

F.B. - The Frankfurt School’s concept of kitsch undoubtedly needs to be reviewed. I think it would make more sense to focus on Nicolas Bourriaud’s idea of post-production. Most of the images in contemporary society are made of already existing material. Originality and creativity belong to a cultural scene dominated by new figures capable of selecting and recontextualizing, like DJs and programmers. This is an approach that could be extended to non-artistic objects, like merchandising, that we have in the book, and that, as we saw, started way before the 1960s. The Raphael-mania that proliferated in Russia in the 19th century was class-blind. It affected everyone, from the people to the Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna, Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky.

P.B. - Francesca, you mentioned Walter Benjamin in the beginning of our conversation. When speaking of images and their reproduction and distribution it becomes mandatory to recall his famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Like some of the artists you selected in the book, such as Vermeer and Van Gogh, Benjamin was reappreciated much later, in this case by Post-Modernism. How valid is Benjamin’s essay today in terms of ‘aura’ and ‘mass culture as an instrument of political mobilization and struggle?’

F.B. - That’s one of Benjamin’s most complex and contradictory essays, but these are qualities innate to his thought, and I don’t think the simplification of the modern-technology-reproductions-of-images-contribute-to-undermine-their-aura formula does it justice. Benjamin actually sees the modification of the relationship between masses and art as a welcome revolution and a necessity of the 20th-century zeitgeist. It’s an inevitable and positive process, as it obliterates the aristocratic idea of art. Benjamin’s idea of decadence was the result of a long series of reflections. He was an ardent supporter of the idea of art as something of social value as opposed to the idea of art as something of exclusively religious value. It was an issue of equality.

P.B. - Adorno’s condemnatory criticism is still very much in vogue in the art world. Reification, commodification, indoctrination, conformism, all of which reproduce personality structures and as such status quo under what he calls “totalitarian capitalism.’ Is there a way we can change this ‘undialectical’ focus between culture and capitalism resulting from a past historical conjuncture? Is Mona Lisa to Marge an attempt to go in that direction?

M.R. - The book is factual. It has historical rather than theoretical pretenses. We were aware from the very beginning that by discussing art on those terms there would have been theoretical implications. I would like to stay away from Aristotelian thinking though. Our representation of the relationship between high art and mass culture doesn’t imply the displacement of theories that criticized it or opposed it, but the fact that we have them associated doesn’t mean that we are endorsing this course of action either. As a pop-culture buff, I have to say that I feel a lot of empathy for some of these reproductions, posters, record sleeves, etc., that we found. Some of them are absolutely brilliant. At the same time, others are embarrassing if not plainly insulting. The fact that to these days I am still in picture-research mode and that new potential material presents itself all the time makes me realize that what we are addressing is a large, ongoing phenomenon, and that the book can only capture part of it.

P.B.- Finally: is art history still the place from which to develop a criticism that takes into account the complexities and contradictions of contemporary society and specifically culture as an ambiguous but at the same time contested terrain beyond the traditional interpretations of bourgeois ideology, manipulation and escapism? Do we still have the right tools to critically interpret actual image-based society?

F.B. - Art history definitely provides an excellent thinking platform for the complexities and contradictions that characterize society. However, precisely because they are complex, they cannot be analyzed with a dogmatic approach. Complexity requires complexity. We cannot get too ideological or political. When we started picture-researching, we accepted the fact that a simple formula to go from icon to mass phenomenon doesn’t exist. There are so many imponderables to take into account, and that’s what makes things interesting, in life as in art.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.