« Feature

A Conversation with McArthur Binion

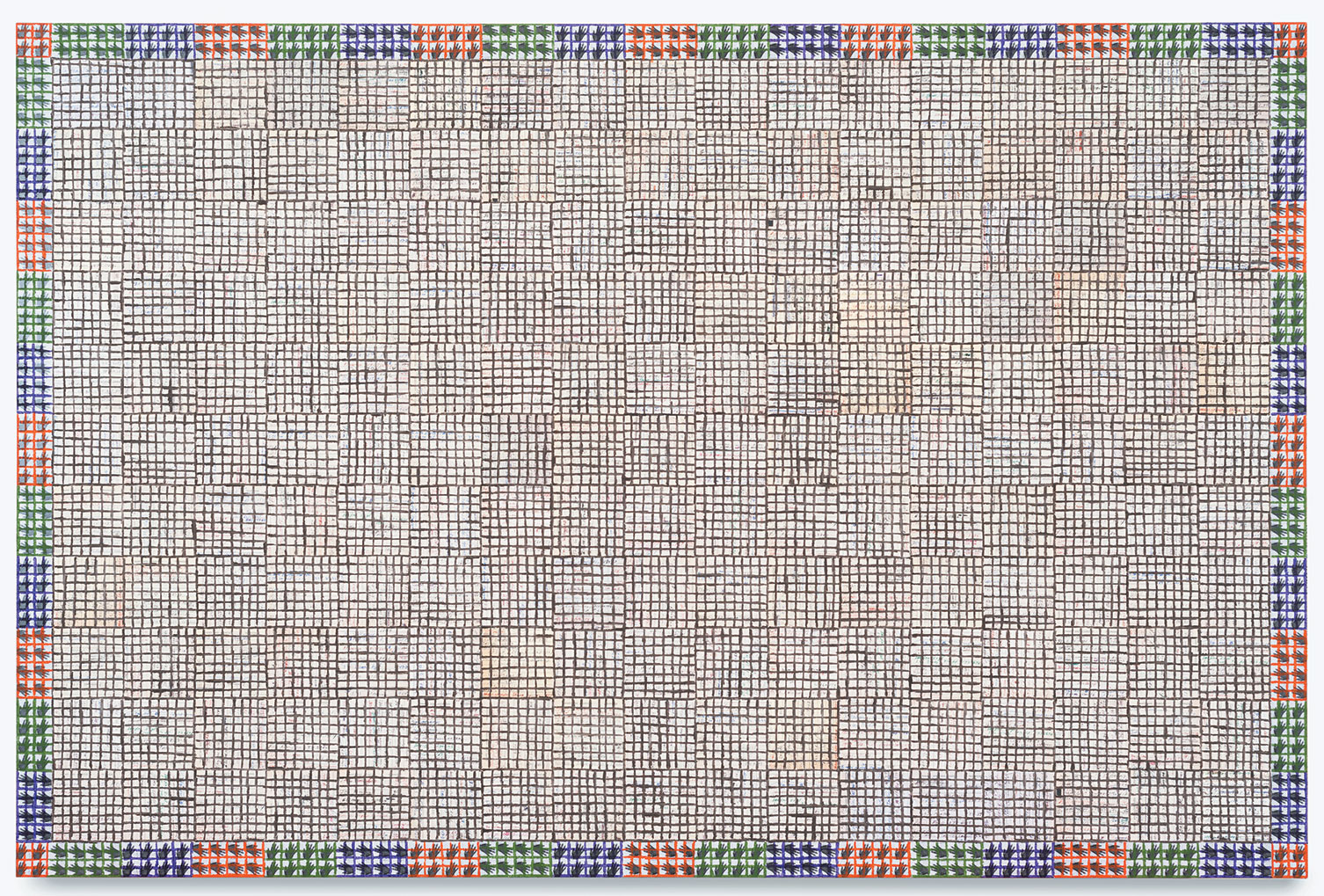

McArthur Binion, Hand: Work, 2019, oil paint stick and paper on board, 48 × 72 × 2 inches. Courtesy of Massimo De Carlo, Milan/London/Hong Kong.

In a career that spans over 40 years, McArthur Binion has developed a unique practice made of abstraction informed by biographical experience. ARTPULSE caught up with the artist after a busy season that saw him having solo presentations of his work in Hong Kong, New York, London and Seoul. Binion, who traditionally shies away from the media, opened up to discuss his work, the context in which it was created, and his future projects.

By Michele Robecchi

Michele Robecchi - Tell me about the exhibition “White: Work” that you put together at the Massimo De Carlo Gallery in London in Fall 2019?

McArthur Binion -It was a huge challenge, because practically no-one does white paints, historically. Kazimir Malevich, Lucio Fontana, Robert Ryman—that’s pretty much about it. I know Robert Rauschenberg did a group of white paintings that Brice Marden actually painted, or repainted for some kind of performance in the 1960s, but for me it was a first. I got into it, and then I got to sixteen paintings, but then it became so difficult, because I realized that by making a white painting exhibition, I was actually making it about color precisely because there’s no color in it. So, I tell you, I will never, ever do another white painting show. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life, because it’s like being in a blizzard—you can’t see anything with this white. I never got lost in painting before. It was a challenge that I think I met, but it was a relief to be done with it. It also just reads really well with the space there.

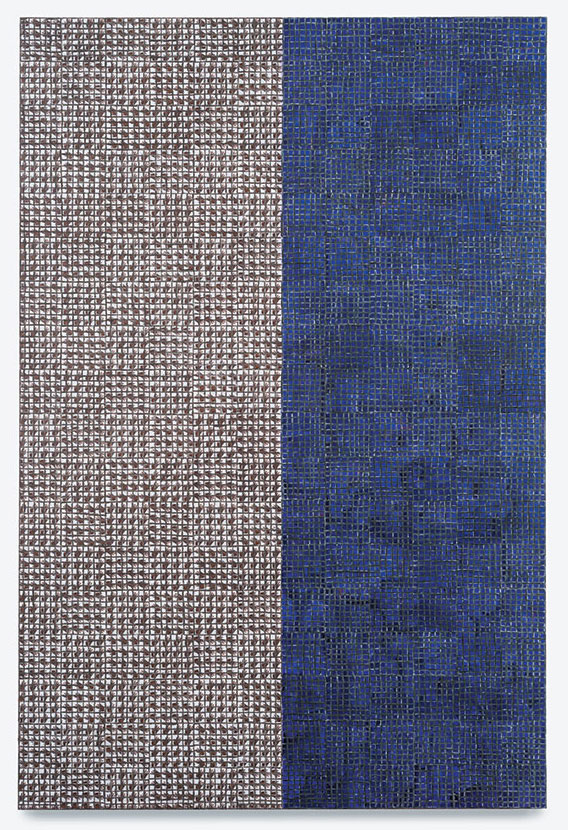

McArthur Binion, DNA: Splops: II, 2017, oil paint stick, ink and paper on board, 96 × 72 inches. Photo: Robert Chase Heishman.

M.R. - Once Charles Gaines told me a story of a panel discussion about the color black that took place in the 1960s. Two of the panelists were Ad Reynhardt and Cecil Taylor and they had an argument over the meaning of the color black, because according to Ad, black referenced a universal idea whereas Cecil thought you couldn’t separate it from experience. Do you think something similar can apply to the color white?

M.B. -There was actually a black painting in the exhibition. That’s me. Because when we started, a whole bunch of us were always the only black person in the room. That’s the black person in the room. I was prepared to wait 40 years before being acknowledged, which I eventually did. Along the way, I sold work, I had my collectors, but I never had a gallery. My first gallery was when I was 65 years old. The good thing is that you learn what not to do. If you find out what not to do, you don’t make those mistakes, it saves you years. I know that if I’d have stayed in New York, this would never have happened. It’s too competitive. Also, it’s a big race now. There’s a correction going on, there’s a whole new market, and everyone’s excited about it. All these major collectors, they have everything already, and now they’re like, “Black artists? Yes.” It’s a whole new thing.

M.R. - I know. Years ago we talked about the “Soul of a Nation” exhibition at Tate, and I remember you were very critical of it.

M.B. -They had poor examples of some of the artists, and the installation sucked. The abstract paintings were this close together. It really pissed me off. People said I should have been in it, but I am so glad I wasn’t, because sometimes you make more things happen by not being in something.

M.R. - So how do you feel about this historical correction you just mentioned?

M.B. -I feel good. The best part about having success, if you could call it that, is being able to help young artists. When I came to New York, my first friends were Jack Whitten, Dan Flavin, Brice Marden, Al Loving, and Mel Edwards. That was a special time, because all the successful artists were very supportive of the young artists. I lived in a five-floor walk-up, and you could actually ask some big, famous artist to come see work, and they would say yes, because the art world was really small. So now I’ve started buying a lot of work and supporting a lot of young artists, which is so fantastic. I love that I’m able to do that. I’m also trying to help them with advice. Some of them are there already, but you need to have the confidence. You need somebody saying, “That’s the way to go, stay there,” And I recently discovered that some of these kids are really interested in my work. So, for me, it was like, “Cool, but you’re not going to come to my studio.” In the last ten years, less than twelve artists have been in my studio. It’s just not something I do.

M.R. - Why?

M.B. -Well, number one, back in the day, people used to come into it and steal ideas. The other thing I learned from that time was that you had to have your own thing, your own flavor. I was the first person to use paint sticks. In 1972, that was my graduate school thesis. It was before they even made these things, and now they’re called paint sticks, but I was using them when they were called marking crayons. They used it for lumberyards and steel mills. I was looking for how to break the tradition of painting and I figured, I can’t use a paintbrush, because it has the legacy. So, I’ve been looking for something, the closest that the color comes out of my fingers, and I started grabbing these sticks of color and paint. When a museum bought a piece from graduate school some time ago, they didn’t know it was from school. They’ll be able to see at some point, “Well, here’s a piece made in ‘73, Serra was ‘74, Basquiat is, like, ‘79, Binion is the catch. Cool.”

M.R. - If you look at art history in the 20thcentury, you notice that a lot has been written about abstraction, because the artists involved in it were trying to make out guidelines for themselves about what it was or could be. And one of the biggest debates was about the possibility of making pure abstraction versus abstraction that uses reality as a starting point. As the color white is traditionally associated with spirituality, is this is something you took into account when you started working on this series?

M.B. -That’s a hard question. I didn’t follow art history, I followed contemporary history. The logic of following art history does not lead to me. So, I got rid of it, but I’ve always used white. If you look closely at the paintings, 90% of them start with white and then color goes over. But I can invert the value of color, of content and everything and that’s why I decided to get rid of the color and leave the white.

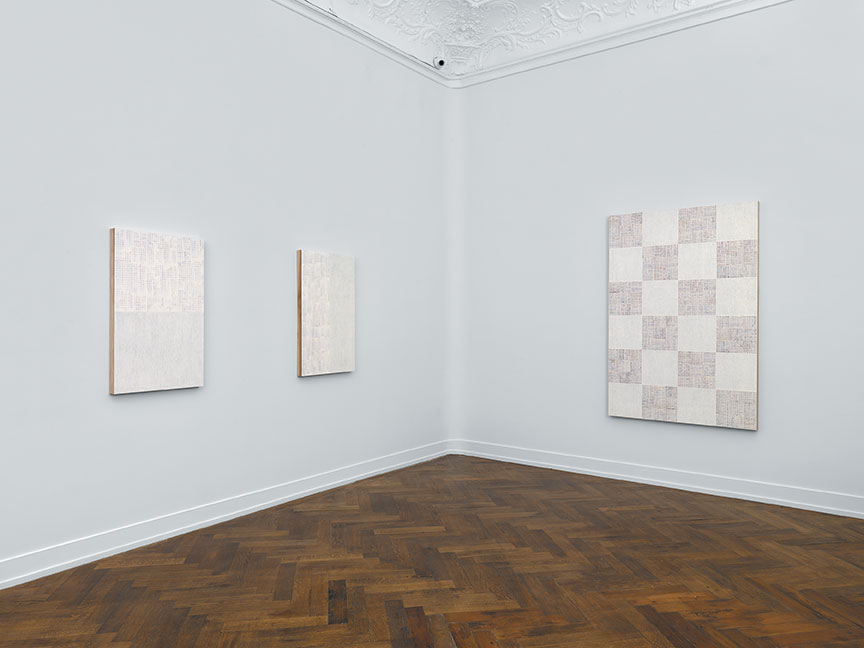

“McArthur Binion. White: Work," installation views at the Massimo De Carlo Gallery, London. ( October 1st – November 16th, 2019). Photos: Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy of Massimo De Carlo, Milan/London/Hong Kong.

You know, when Wifredo Lam went to Paris, Picasso embraced him. Lam was the embodiment of everything Picasso wanted to be—African, Cuban, etc. Picasso actually had his first show at the Perls Gallery in New York with Lam in 1939, I think. Lam is the person that’s key to me along with Jack Whitten, my friend who passed away two years ago. I feel like I’m on the line, but then I also have to carry on for Jack. It’s a challenge, and I love the challenge. You have to have a problem, because you set a problem and you solve that problem, and that’s how each show, to me, is. I’m trying to not put anything in, so, everything I’m doing is going out. I try just to listen to myself.

M.R. - When people like Whitten or Sam Gilliam started working, many people felt that by doing abstraction they were washing out their identity. Did you ever have to confront that kind of criticism within your work?

M.B. -No, people were afraid to criticize me. I know the argument-”If you make black art, it has to be recognizable,” but to me abstraction is recognizable, although you are an island.

M.R. - Some of your abstraction is, to a degree, rooted in realism. I’m thinking for example about the DNA series…

M.B. -The DNA series started in New York in 1972. I used my address book, and it’s the entire social DNA. Everyone I ever sold a piece to, everyone I went out to, everyone I met. But then in the 1990s you didn’t need a phone book anymore, because there was a computer then the cell phone. I don’t know if it’s realism, but it is my reality.

“McArthur Binion. White: Work," installation views at the Massimo De Carlo Gallery, London. ( October 1st – November 16th, 2019). Photos: Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy of Massimo De Carlo, Milan/London/Hong Kong.

M.R. - Language seems to be very important in your work.

M.B. -I think you have to have your own language, because otherwise it’s not special. Words are very important to me, because I had a speech block as a kid. So I figured out a way of non-verbal communication, and that’s how I became a painter.

* This interview was conducted in Spring 2020.

Michele Robecchi is a curator and writer based in London, where he is a Commissioning Editor for Contemporary Art at Phaidon Press. Some of his recent publications include monographs on the work of Sharon Hayes, Yayoi Kusama, Adam Pendleton and Adrián Villar Rojas. He was one of the curators of the 1st and 2nd Tirana Biennale.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.