« Features

Nicole Eisenman: The Relevance of 21st-Century Expressionism

By Stephen Knudsen

Anyone following the long career of New Yorker Nicole Eisenman is familiar with the artist’s sociological paintings cast with farmers, fools, fantasizers, clowns, coaches, zoomorphs, oglers, artists, bohemians, beer drinkers, sloggers, swimmers, gropers, tea-partiers, sailors, girls, superheroes, birds, friends, mothers, monkeys, asses, nudes, fantasizers, cats, friends, paranormals, fanatics and stripped-bare maidens. How often does one get to say that about a relevant painter anymore? Kind of fun…1

So, what is the latest big news with Nicole Eisenman? She just proved a narrative Expressionist painter can still win one of those big art awards, as her work just won the Carnegie Prize at the 2013 Carnegie International in Pittsburgh. Founded in 1896 by Andrew Carnegie, the International is the second oldest survey of contemporary art in the world after the Venice Biennale. This year’s International includes work by 35 artists and collectives from 19 countries. Eisenman’s entry was a survey of her work from the early 1990s to 2011.

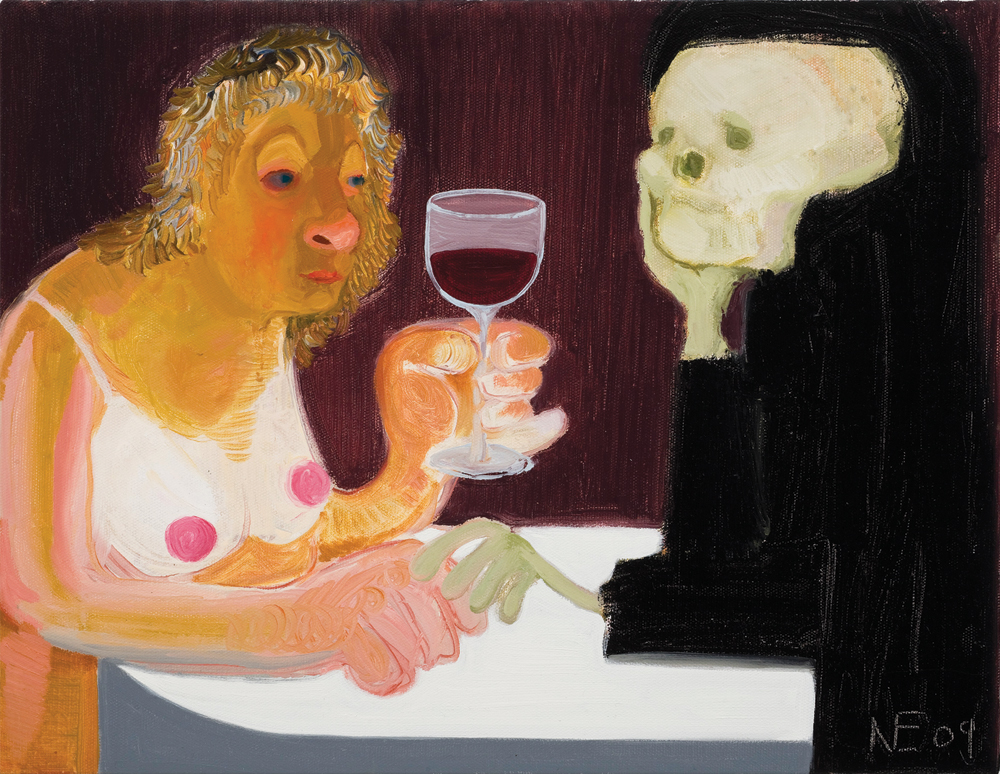

Nicole Eisenman, The Sunday Night Dinner, 2009, oil on canvas, 42”x 51”. Collection of Arlene Shechet and Mark Epstein. All images are courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York. Photos: Thomas Mueller, New York.

Eisenman’s buffoonery, irony and satire rises above empty jokes. The work has a true over-lay of expressionism that casts back to Edvard Munch, the father of expressionism, more than it recalls the inferior work of the Neo-expressionists in the 1980s.

Perhaps a little comparison of two dinner paintings will illuminate here: Sunday Dinner by Eisenman and The Wedding of the Bohemian (1925) by Edvard Munch. In Eisenman’s Sunday Dinner, the guest of honor, in full Sharon Stone exposure, takes on the male gaze. We’re sexual beings and oglers. What is the urban legend? A sexual thought every seven seconds for males. For a more valid, yet still hearty number on this, we could defer to a study done on Ohio State University College students published in the January 2012 issue of the Journal of Sex Research. The median number of times per day men in the test group thought about sex was 19, as compared to 10 for women.

In Sunday Night Dinner, more than meatballs are being devoured in this strange presentation that recalls and amplifies Manet’s mischief with the same motif. Munch also places a woman (in this case a bride) at the center of dour behavior that is strange, considering that it should be a happy occasion. Like Eisenman, there is both male and female angst, but without license to goof around. In Munch’s expressionism, anxiety, jealousy, sex, death and all the other usual suspects were not exactly big laughs. And that seemed just about right for Munch. His genius rose elsewhere.

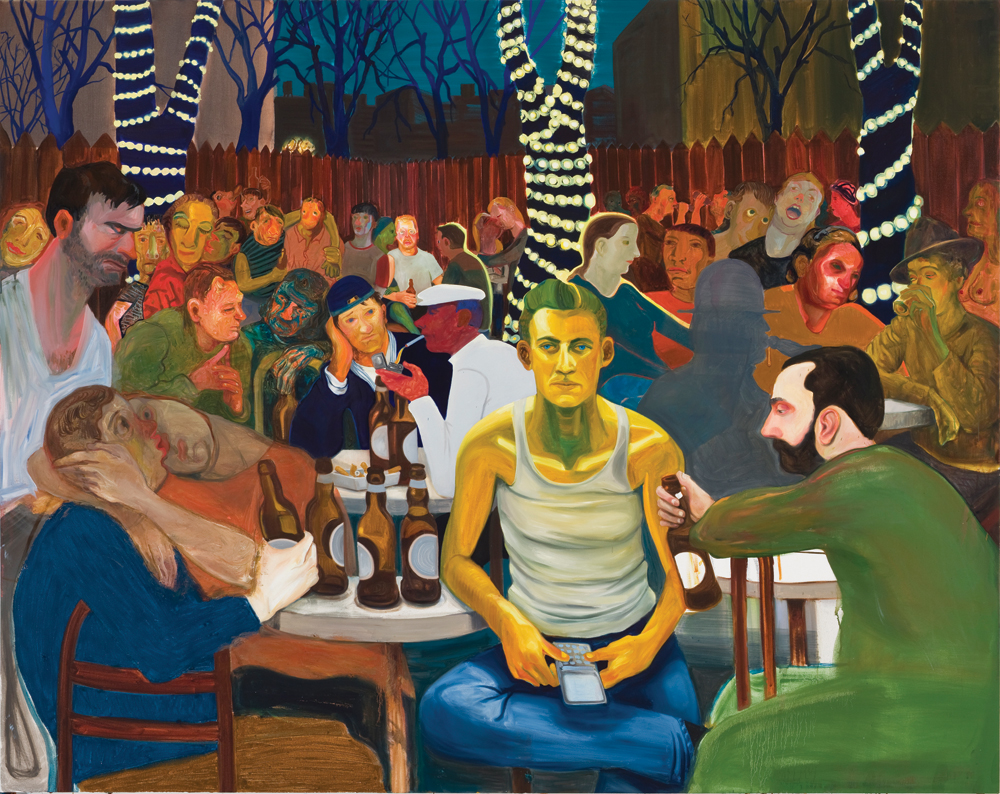

Nicole Eisenman, Beer Garden with Ash, 2009, oil on canvas, 65” x 82.” Private collection, Switzerland.

Eisenman and Munch start to correlate again, though, when we consider at formal qualities. Both compositions have excellent design and place viewers right at the table. Both works have heightened color, visceral scrubbing and reliance on line to do a lot of the work. Eisenman does conjure up a bit more of Van Gogh than Munch does, especially in her foreground figure sipping wine. For the quirky, devilish figure (lower far-right corner), she slaps down thick paint and gouges into it with the brush handle. Munch used the brush handle and thick paint at times as well, but in other paintings.

If you can not make it to the Carnegie International, aim for the much larger survey of Eisenman’s work: “Dear Nemesis,” at the Contemporary Art Museum in St. Louis, the largest collection of her work to date, with more than 120 paintings, prints and drawings from the 1990s to the present. The Triumph of Poverty is one of the best inclusions in the exhibition, which runs from Jan. 24 through April 13.

Eisenman’s sociopolitical angst is vented in works such as The Triumph of Poverty, a history painting that delivers an indictment against the worldwide economic crisis that peaked in 2008—a 21st-century Grapes of Wrath.

Nicole Eisenman, Death and the Maiden, 2009, oil on canvas, 18” x 14 ½”. Collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg.

In The Triumph of Poverty, one is tempted to identify a defunct commander-in-chief: the ass-backwards leader of the blind (tethered and stumbling) that Eisenman lifted out of The Parable of the Blind by Peter Bruegel, the Elder. Though she told me that she wasn’t thinking of President George W. Bush per se, she said, “That guy is wearing a top hat, forever a symbol for Generic Capitalist Guy. He also reminds me of the German curator Kasper Koenig.”

The Triumph of Poverty has a way of sticking in the memory, and like the very best history painting, it transcends its own moment and speaks to the broader scope of human issues. And that is as true of Eisenman’s The Triumph of Poverty as it is of the painting it reenacts: Hans Holbein the Younger’s painting of the same title (c. 1533).

It is worth noticing that a more upbeat painting, Beer Garden with Ash, was painted in the same year (2009) as The Triumph of Poverty. Though Eisenman’s beer garden works pull from the good energy of Post-Impressionist café paintings, I asked Eisenman if Beer Garden with Ash was still tied to crisis. She said:

“Yes, (both paintings are) varying responses to economic collapse, a time of deep pessimism. In paintings like Beer Garden with Ash I was also looking at community and chosen families, letting my work be a kind of bridge activity to deepening connections with friends. At that time I was having friends and acquaintances come to my studio and sit for me. It was a way of making connections, yet it’s a strange social activity. Painting is lonely. Sometimes you just want people in your studio and you figure out a reason to get them there. I think of whom Van Gogh chose to invite into his studio—sometimes you just need people around, even the postman.”

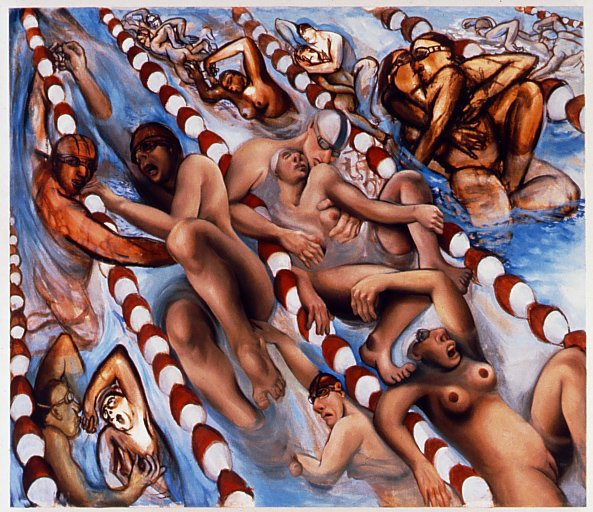

I was glad to see one of Eisenman’s best early paintings in the Carnegie International. Swimmers in the Lap Lane (1995) must seem like a bizarre painting to anyone who has never crowded into a lap lane. As a swimmer, though, I identify with this painting, and I asked Eisenman about the pseudo-intimate nature of swimming like this with a bunch of folks, sometimes strangers and sometimes teammates.

Nicole Eisenman, Swimmers in the Lap Lane, 1995, oil on canvas, 51x39 inches, Collection of Dianne Wallace, New York

She said, “I’ve spent plenty of time in the lap lanes. I was an avid swimmer as a teenager and eventually started doing triathlons. There is amazing synchronicity amongst a string of lap-lane swimmers; in my mind, it is a very sensual activity, though it can also be, as you probably know, tortuously boring.”

But what makes this a memorable painting is the unpredictable composition. For example, look at the ring of five hands in the center of the composition and notice how everything spins out from there, with the diminishing of figures in all directions. Relative sizes break logic in service to composition and the sensation of the strange world 50 laps can put the mind in. The composition delivers a sort of a Petri dish of human interaction, both sexual and social.

Eisenman is in the vanguard of 21st-century Expressionists that overlay Edvard Munch, James Ensor and the German expressionists Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Otto Dix. And the list goes on. However, Eisenman is much better, in a Robert Hughes kind of measure, than 1980s Neo -Expressionism, at least the kind that reigned over most the art market that decade. Not all, but a lot of that “bad” painting that was so exalted at the time has turned out to be just Bad—in a what-were-we-thinking kind of way. In this mostly male dominium, the worst offenders were David Salle and Julian Schnabel. The late art critic Robert Hughes, though, was never a believer in it. He was turned off by the lack of technical skill, as well as the inability to draw the figure, and construct a decent composition. He said of such painters “I don’t like art that thinks it is enough to quote the high achievements of the past—that pretends to be heavy and then takes itself lightly. It merely puts you in a kind of free-floating zone.”2

Hughes’ 1980s argument proved itself overtime. Consider the forgetfulness that museums have regarding Neo-Expressionism. In a February Art in America essay last year, “Neo-Expressionism Not Remembered,” Raphael Rubenstein reminded us that the last time we saw a “big show” by a “Neo-Ex star” in a New York museum was Francesco Clemente’s Guggenheim retrospective in 1999.

But the 1980s Neo-Expressionism had bright spots, and even Hughes held a little more regard for Eric Fischl, a painter that I have robustly defended elsewhere.3 Gems like Fischl’s Old Man’s Boat Old Man‘s Dog (1985) are not so easily dismissed. In addition, Hughes had high regard for peripheral figures: Susan Rothenberg for one. Arthur Danto recalled the exuberance of the period in observing that Neo-Expressionism brought with it a joy that figure painting was back, and he aptly recalled that the “Inaugural exhibition of the redesigned Museum of Modern Art in 1984 made it appear as if Neo-Expressionism was a worldwide phenomenon.”4

Eisenman‘s work is respectful to its early 20th-century roots by not making formal aspects of painting into a joke. She mixes in 1920’s formal debauchery into her strong compositions and skill in rendering. It comes down to the old but useful cliché: Knowing how to draw informs good distortion. It is worth noting that she preaches what she practices. For example, she held a figure-drawing atelier at the 2012 Whitney Biennial in which a hundred volunteers drew nudes from direct observation.

Eisenman exercises those skills in Expressionistic idiosyncrasy: soul bearing, reckoning with absurdity, and acknowledging the joy, pain, embarrassment and ecstasy of being human. Her work revives ideas in M.H. Abrams’s classic book The Mirror and the Lamp, in which the lamp represents the inner flame—the soul, the mind, the spirit, expression—what, for some, art is all about.

Eisenman is not alone in lifting expressionism into a notable resurgence. Here is the short-list of current painters with similar wit and expressionistic bent: Dana Schutz, Cecily Brown, Summer Wheat, Natalya Laskis, Trenton Doyle Hancock, Helen Verhoeven, Matt Blackwell, Judith Linahares, Greg Eltringham, Robert Barnes, David Humphrey, Paula Rego, Harumi Abe and the Cynical Realists in China. The differences in these artists are similar to differences in early 20th-century Expressionism. For example, Summer Wheat is to Eisenman as Oskar Kokoschka was to James Ensor.

All of these short-list artists show conceptual mischievousness on par with Eisenman. For example, Summer Wheat’s Preacher is from a series of drawings she made titled Kama Sutra USA. In an interview, Wheat told me she was thinking about the luminous and mystical images from non-Western depictions of Kama Sutra and thought to compare that to what the American version would be, which, in her mind, would look more blatant and crass and be absent the mystical.

She did a series of drawings in which she took one word and drew the sexual world around it. “Preacher” was one of them, as well as “Budweiser” and “coach,” among others.

In a final question I asked Eisenman for the meaning of the title of her upcoming CAM St. Louis show, Dear Nemesis. Her words are a good way to go out:

“Nemesis is the Greek god of retribution, specifically for the crime of indiscretion, of hubris. If you start to think you’re a god, she’s the one who will put you in your place. Maybe she pays extra attention to artists, since it is our job to create something out of nothing.”

It is Nemesis who steps in and introduces the struggle into the process. I make frequent offerings to her in my studio to get her off my case.

NOTES

1. I opened a recent Matt Blackwell (on my shortlist) review in a very similar way. See a related review at: <http://www.nyartsmagazine.com/?p=8686>

2. Boynton, Robert S., The Lives of Robert Hughes, May 12, 1997, The New Yorker. Note: In December 2013 I confirmed via email with Boynton that he directly quoted Robert Hughes via an interview for this article.

3. See, Knudsen, Stephen, Beyond Postmodernism/”Putting a Face on Metamodernism without the Easy Clichés”, ARTPULSE, No. 14, Winter 2013.

<http://artpulsemagazine.com/beyond-postmodernism-putting-a-face-on-metamodernism-without-the-easy-cliches>.

4. Danto, Arthur C., Unnatural Wonders/Essays from the Gap Between Art and Life. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007, p. 16.

Stephen Knudsen is an artist and a professor of painting at Savannah College of Art and Design. He is the senior editor of ARTPULSE, a contributing writer to NY Arts Magazine, Hyperallergic, the SECAC Review and The Huffington Post, and the senior editor of the anthology The Art of Critique, which will be published in 2014.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.