« Features

Nothing Meets the Eye: An Interview with Matt Sussman

When reflecting on a work of art, how often is the object of your attention a reproduction rather than the original? I’d guess it’s more often than you care to admit. Matt Sussman is an Oakland-based writer who earlier this year wrote a series of essays exploring “the aesthetic and affective fallout of some of the odder, ubiquitous, and more stubborn byproducts of our culture of copies, reproductions, and fakes.” Known for his writings in the San Francisco Bay Guardian, Art in America and BUTT Magazine, Sussman writes on the cultural edge with a contemporary voice aimed at discovery. His appropriately titled series “Nothing Meets the Eye” is posted on SFMOMA’s Open Space blog. The series of five posts encompass a range of topics focused on the relationship between perception and authenticity affecting us all.

Sussman’s ideas pertain directly to us starting our days by swiping through an array of media to stay current. A byproduct of this is that when we find an interesting work of art we search for more about it online; we don’t visit a museum to burn an image of the original in our memory. I suspect that today we derive most of our opinions concerning artwork from sources other than that which the artist made. Even for those who’ve seen Jackson Pollock’s One: Number31, 1950 in person at the MOMA, we surely are corrupted by the number of times we’ve Googled “Pollock drip painting,” or something to that effect.

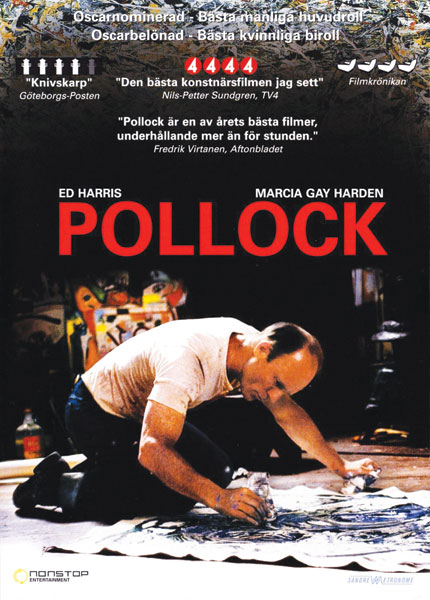

Who knows how far removed or distorted the images we view through the Internet or movies are. Thus, we have to realize our emotional investment in the original is shaped in large part by the online experience. Even in artist documentaries, in which the directors attempt to re-create the most realistic sense of the artist’s life, they often commission fakes as props to appear in scenes. Most notably was the case in a biopic of Jackson Pollock staring Ed Harris. The paintings in the film were actually copies commissioned with the backing of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. He later curated an exhibition of these titled, “Not Pollock, Not Krasner.”

In a sense, Sussman’s control group in his reflective experiment consists of the art by Elaine Sturtevant, who made a career producing closely matched renditions of popular artworks of her time. These included those by Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Robert Gober and many more. Never intended to be misunderstood as the real thing, her works always included a tell-tale sign distinguishing each as an original Sturtevant.

Recently, I had the opportunity to ask Matt some questions about his “Nothing Meets the Eye” series. As always, his views are keen and insightful.

Scott Thorp - The world of art has always been filled with copies and fakes. Artists emulate each others’ work and copying masters is at the core of art education. So in some ways, the conversation around artistic authenticity is more a pedantic exercise than a practical discussion. If people were to try and find a work truly original in either form or content, they’d have a tough time doing so. While the discussion about authenticity isn’t new, the concepts you explore in the five essays comprising “Nothing Meets the Eye” point to some key sensibilities shaping contemporary society. In my mind, these ‘ubiquitous…byproducts’ as you discuss may form more of our reality than what historically has been considered real. Can you explain what it was that spurred you to write these articles and what was it that you were trying to achieve?

Installation view of “Sturtevant: Double Trouble,” March 20–July 27, 2015 at MOCA Grand Avenue. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Matt Sussman - You are right to say that the conversation around authenticity is itself less interesting, precisely because it is old hat by this point. That we are so inundated by and inured to copies and reproductions is simply a fact of our social media and smart phone-saturated lives, never mind all the ways in which contemporary art has called into question and re-reified originality. When I was first thinking about what I’d write for Open Space, I considered just focusing on the replicas of artworks created for artist biopics. But, after sitting some more with the Sturtevant exhibition I saw in New York, I realized that I could make a broader inquiry into the wide array of unoriginal ‘visual artifacts’ that we live with and which circulate among us. What interests me, and what I set out to explore in my blog posts, is how this routine exposure to these byproducts has changed how we feel about them, and how those feelings shift our investments in art, whether we’re looking at something on screen in a movie theater or on a tablet while commuting or in a museum, when we’ve set aside time specifically for aesthetic engagement.

S.T. - It’s interesting to think of how casual exposure to these replicas alters our investment in the art they represent. So is it your opinion that artist biopics lessen the aesthetic experience of the artist’s work in that biopics create a new set of elements affecting the context of the original? And maybe they do it even more so when authorized by the artists themselves as in the case of Lee Krasner. Jumping right into a deep pit of dialectics, can you also explain a little more about what you mean when you use the term ‘investment?’

M.S. - I don’t know if artist biopics ‘lessen’ our experience of a particular artist’s work so much as they present another instance of seeing that work reproduced. And seeing art in reproduction is simply how most people tend to encounter it. So, they augment how we come to visually recognize a certain artist, and, in turn, what we may or may not think about their work-regardless of whether or not we’ve ever been in the presence of the original.

But unlike, say, the results of a Google image search, artist biopics do provide an interpretive overlay to what we’re seeing and, depending on the movie, that interpretation can be more didactic or more diffuse in how it encourages us to connect the dots between an artist’s life and their work. That interpretive bent also reveals something about the filmmaker’s investment in their subject and what’s at stake in their film: for many reasons, Ed Harris doing Jackson Pollock is not the same thing as Derek Jarman doing Caravaggio.

Another crucial difference between a digital photographic reproduction and what we’re seeing in artists’ biopics is that so often the latter involve authorized copies carefully fabricated by scenic artists. There are actual paintings in these films, which, in other contexts and with differing intent behind their creation, could be called forgeries. The Pollock-Krasner House recognized that attendant risk as very real and made sure to painstakingly document all the copies of Pollock’s and Krasner’s work created for Pollock much in the same way that they would authenticate a genuine Pollock or Krasner canvas.

What’s curious to me was their decision to give the copies their own exhibition. I think their intention was partly to disprove the idea that anyone could paint like Pollock, but, without any originals to allow for side-by-side comparisons, I wonder if the net effect wound up being less cut-and-dry. These were all copies that were meant to show up as convincing on camera. And to the amateur eye they do, which-to get to your question about investment-leads me to ask what makes a work of art count as a Pollock to someone as opposed to an appraiser? To flip the terms: What are the qualities of ‘Pollock-ness,’ perhaps intuited through frequent exposure to reproductions of actual Pollocks, that a viewer throws back onto a painting that is merely Pollock-like? And could the experience of seeing an actual Pollock-after, say, seeing it re-created in a movie-potentially be underwhelming? Harry Moses’ wonderful 2006 documentary Who the #

amp;% Is Jackson Pollock? is a wonderful exploration of this gray area.

Poster for Pollock, 2000, a biographical film directed and staring by Ed Harris that tells the life story of the iconic Abstract Expressionist artist. Image courtesy of Matt Sussman.

S.T. - The ideas about perception from the German philosopher Walter Benjamin align with what you are describing. He explained perception as not only a component of biological functions, but also comprised of historical context. This matches well with how you are describing Google searches as adding an interpretive overlay to what our understanding. In his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” he uses the term ‘aura’ as a phenomenon of distance from the original. How do you see Sturtevant’s work in the context of Benjamin’s philosophy?

M.S. - Although there isn’t space for me to answer your question to the full extent that it merits, I would say that, first, it’s important to note, as many scholars have, that Benjamin’s use of ‘aura’ throughout his career was multivalent. The sense in which he uses it in the work of an art essay-as primarily an aesthetic category threatened by then-emergent technologies of reproduction, namely film-revise earlier notions of the aura as a kind of ‘medium of perception,’ to use film scholar Miriam Hansen’s phrasing, which is where I think Sturtevant’s art comes in. Sturtevant’s work encourages the kind of distanced contemplation Benjamin locates as a quality of auratic (i.e. non-mechanically produced) artworks, but it also functions as an auratic medium itself: The fact that her pieces are meticulous and handmade in their own right is part of what forces us to reckon with how we develop a sense of what makes a particular artist’s work their own within a field run amok with copies and reproductions.

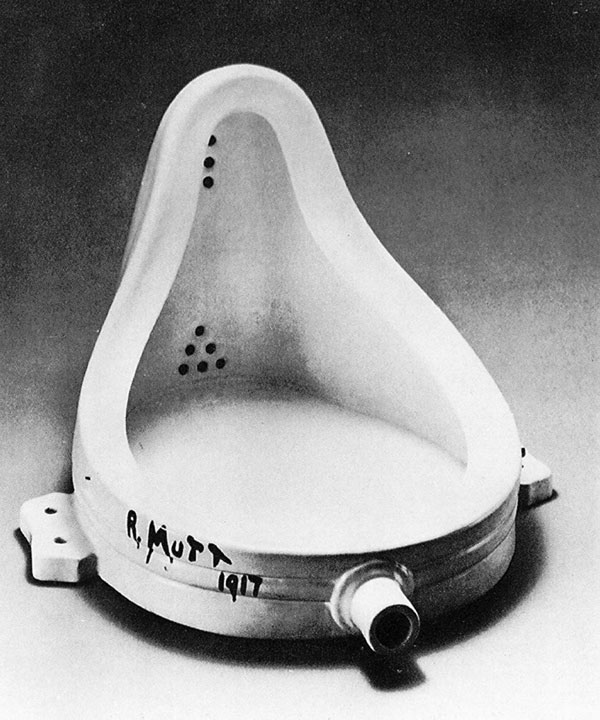

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain by R. Mutt. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz, Source: Wikipedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Duchamp_Fountaine.jpg.

S.T. - This conversation consistently reminds me of Marcel Duchamp and his readymades. The artist biopic relationships you speak of and Elaine Sturtevant’s works seem directly connected with Duchamp’s push for the visual elements of art as being ancillary to the conceptual components of it. His famous urinal titled Fountain may be ground zero for all this. Interestingly, the original for Fountain doesn’t exist. Only the concept and replicas remain.

Whenever I see one of those Fountain replicas commissioned by Duchamp, I’m fooled for a second into thinking it’s the original. For that moment, I’m not in on the irony of the situation. With Sturtevant’s work, though, that moment doesn’t occur for me because she leaves telltale signs differentiating her work from the original. I don’t believe she had intentions of fooling the viewer. Her work possesses a different sense of irony.

In your introductory post for “Nothing Meets the Eye,” you describe an interesting experience at MOMA while viewing Sturtevant’s work. You state, ‘I chuckle, partly to reassure myself that I’m in on the joke hanging in front of me, but also as a preemptive defense in case I’m not getting the joke. But as I keep on looking, it dawns on me that what I’m looking at might not be a joke at all.’ I think we’ve all been in that situation where we are sure we ‘get it,’ and shortly thereafter something flips to where we find ourselves outside the artistic conversation and parameters of understanding. Can you discuss your experience a little more and also the difference between your understandings of her work now-after you’ve written “Nothing Meets the Eye?”

M.S. - With Duchamp’s reproduced urinals you have a second-tier removal of the artist from the art object. As you suggest, Duchamp enlarged the conceptual frame beyond merely reclaiming the providential, mass-manufactured artifact. The question then becomes, what happens to the readymade when it is subject to the same logic and processes of production that resulted in the original urinal’s manufacture?

I think what I found disarming in that encounter with Sturtevant’s work, in the MOMA installation, was that it ultimately wasn’t ironic. The aim wasn’t parody or to fashion a more elaborate set of air quotes. Apprehending the art as a joke was almost a defensive response on behalf of how her art truly unsettles. It was impossible not to think of her work in relation to the original work, but, after having spent more time reflecting on her work (and certainly, Bruce Hainley’s writing on her was formative here), I think that is also the challenge her work poses: to rethink our relation to the original pieces and to rethink by what aesthetic qualities and criteria-beyond the artist’s signature-those originals have settled into their status as such. It’s almost as if her pieces’ resemblance to other artists’ work is an unavoidable byproduct of the same exercise.

In a way, she’s like a police sketch artist drawing up suspects from composite descriptions. Inevitably, there’s a mismatch when the portrait is compared to, say, a mugshot, but it’s the overlap between the two that is haunting, that is the margin for verifiability.

S.T. - Nicely put. The tension created by the overlap is indeed haunting. And the margin between the two seems to evolve as Sturtevant’s work becomes more deeply indexed in the annals of art history. As a final question, and to bring us around to the opening of our conversation, if a friend were to ask you to explain the role of authenticity in art today, what would you say?

M.S. - That’s quite the closing question. I would say that despite successive critical and artistic interventions over the past, say, six decades that have rigorously interrogated authenticity’s relationship to authorship, both the market and the art-going public are still deeply invested in the genuine article. Individual artists fetch higher and higher prices at auction, and museums have increasingly made traveling, mid-career and posthumous surveys centerpieces of their programming. Both phenomena attest to the continually rising stock of the artist as Artist, i.e., as the sole originator of a work of art. That said, I think the lasting impact of much recent post-Conceptual art-art that can be said to have been made under the rubric of social practice, in which the work is constituted by an individual or group experience as mediated by an environment or set of conceptual considerations put into place by the artist-has changed the terms of what shows up as authentic. Authenticity can now be gauged solely through one’s personal or affective experience of the artwork, as opposed to having that personal or affective experience be predicated by being in the presence of an authentic artifact.

Installation view of “Sturtevant: Double Trouble,” March 20–July 27, 2015 at MOCA Grand Avenue. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

I also think that, thanks to the Internet and social media, we have expanded our limits of comfort living with replicas, fakes, alternate identities, publicly shared fantasies, collaborative authorship and open texts. The notion of a destabilized, continuously performing self is no longer a radical proposition for art to make; in some ways, it’s just part of being online on a day-to-day basis. However, we continue to live in a society in which the notion of a destabilized self might itself be a luxury. For some bodies and persons whose differences are routinely marked and policed as such, ‘authenticity’ becomes the at-times putative measure by which one-and, by extension, the art one makes-is recognized or judged. In this way, authenticity still remains pernicious and suspect despite a well-documented history of attempts to undermine its validity as a concept.

Scott Thorp is an artist, writer and educator specializing in creativity. He is chairperson of the Department of Art at Augusta University, as well as a contributing writer and editor for ARTPULSE. Additionally, he serves on the board of directors for Westobou Festival and is vice president of the Mid-America College Art Association. With an MFA in drawing and painting from the Mount Royal School of Art at the Maryland Institute College of Art, he has exhibited often in museums and galleries in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S., including the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.