« Feature

The Rhetoric of Rank

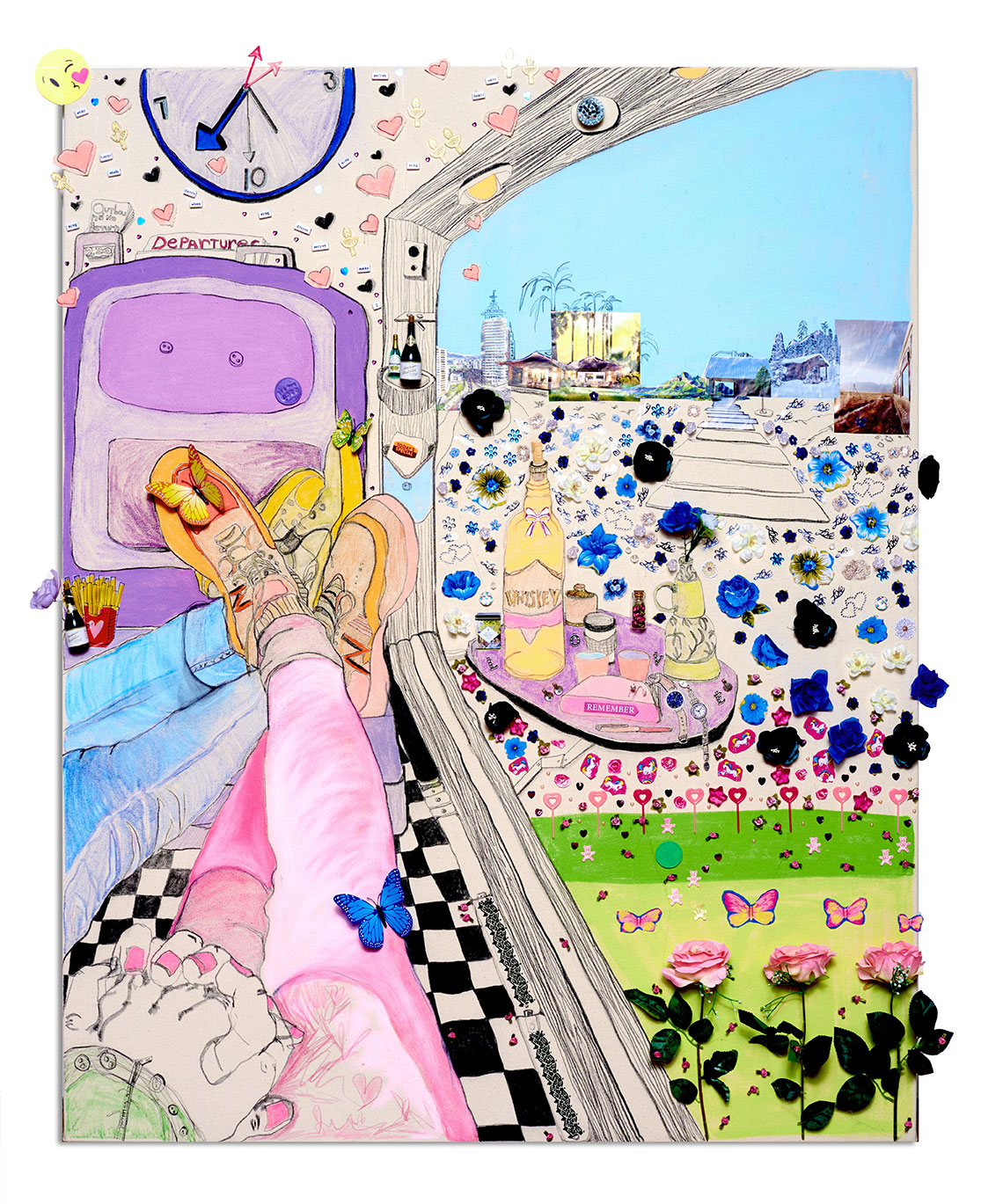

Gretchen Andrew, Art Basel Miami Beach (Dress for the Job you Want, Not the One You Have), 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Gretchen Andrew is a rule-based artist challenging power structures by following the rules. Gretchen works in the realm of Google’s optimization algorithms to demonstrate she’s the “most relevant artist, ever.”

By Scott Thorp

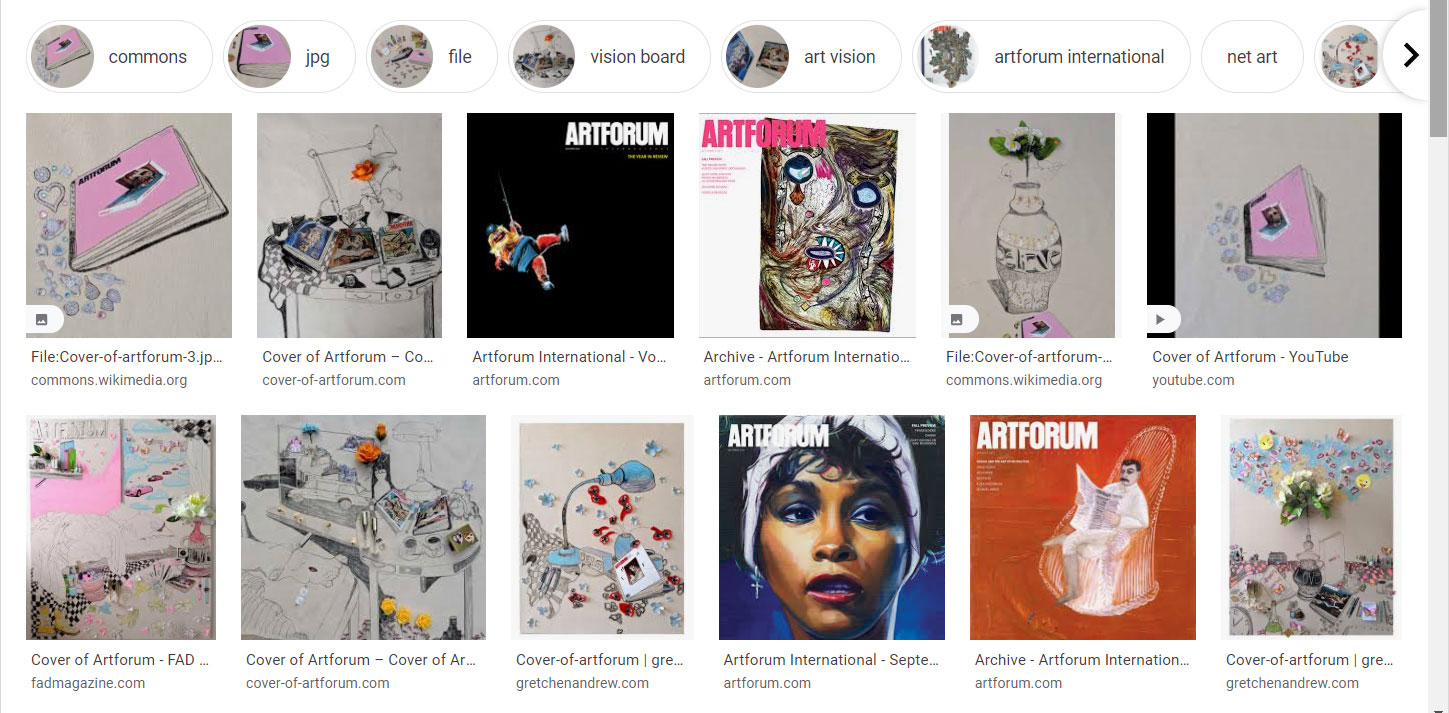

To play her game, simply Google “cover of Artforum” or “Frieze Los Angeles.” Click on the image results and Gretchen’s brightly colored vision boards dominate the page. They stand out as mixed-media collages adorned with line drawings, fake flowers, heart stickers, and all sorts of crafty-bling best categorized as ephemera. She describes the aesthetic as highly feminine, one of a teenage girl. The last time I looked, eleven of the top fourteen results for “cover of Artforum” were her works.

However, Gretchen Andrew has nevergraced the cover of Artforum. Nor has she exhibited in Frieze Los Angeles. But, as a viewer, I tend to believe she has. After all, I saw it on the Internet.

Gretchen operates as a self-proclaimed “search engine artist” and “Internet imperialist.”(1) These are terms she invented to describe her practice of gaming Google’s artificial intelligence to render her work as being the most relevant to specific keyword searches. “Search engine artist,” is her practice, “imperialist” her goal. She combines images with text and hordes of metadata to form a manipulative digital rhetoric targeting the shortcomings in Internet logic.

In the larger sense, her work lands in the growing realm of net art where the likes of Cory Arcangel, JODI, and Constant Dullaart hijack Internet ecosystems as a forum for multi-media expression. It’s a growing field that blends coding, videos, performance, and misinformation, with a lot of mischief to create a never-ending interactive artistic exposé. With a degree in Information Systems from Boston College, Gretchen is very comfortable with technology. The “art” part is what’s new to her. She only declared herself an artist after resigning as one of Google’s People Technology Managers.

Although not a traditionalist, she honed her art skills the old-fashioned way as an apprentice in the studio of British figurative painter, Billie Childish. Childish paints loosely figurative works chronicling a history of addiction and abuse. Under his tutelage, Gretchen emulated her mentor’s technique and compositional approach. “I’d work in his studio all day, and then I’d go home and recreate his paintings as practice.”(2) She posted finished works on social media, tagging them appropriately as being “After Billy Childish.”Over time, Google began to associate her works with the words “Billy Childish” more so than Childish’s own paintings. When her works supplanted Childish’s originals in searches, the strange reality of the Internet presented her an opportunity.

Since then, she’s transitioned from figurative painter to a combination assemblage/ search engine artist, targeting keyword searches related to the art world’s most coveted events: Turner Prize, Art Basel Miami Beach, Frieze Los Angeles, and Whitney Biennial 2019. In addition to uploading multitudes of vision boards, social media posts, and odd comments she sometimes creates video performances of staged art parties accompanied by commentary like, “I hear the Art Basel Miami Beach art fair is one hell of a party. While I’m not yet technically invited I’ve been dressing for the job I want, practicing being an exhibiting artist who attends all the super cool parties with loads of celebrities.” On her site, you can see her dressed to party, cavorting and drinking champagne with friends.

Gretchen Andrew, Best MFA (Radio), 2020, charcoal, Dream Journal, valentine, and wooden car on canvas, 36" x 24." Courtesy of Annka Kultys Gallery.

At first glance, it’s hard to make sense of what she does. Her digital profile doesn’t conjure up what one would consider an imperialist. Her Pinterest account has a mere 128 followers. And she’s attracted 3,200 Instagram followers, respectable, but not even mid-range influencer status. Her blogs ramble as though she forgot to edit. But that’s okay-according to her, her content isn’t targeted at humans. “The blogs are one form of remixing text that seems like total nonsense or on the bridge of nonsense to humans. But the computer will read it and all it reads is that my images are relevant to the search “best MFA.” The language doesn’t have to mean anything to humans. But it has to be relevant to Google.” And relevance to Google is all she needs. After six years, her work is paying off. She’s racking up shows and selling vision boards.

Internet Logic

Gretchen and I spoke just before her New Year’s Eve digital detox (something we all should try). In our conversation, she described her work as being co-authored by Google’s AI. She supplies data; it filters and ranks. She toys with what it prefers. According to her, the innovation in her work isn’t that she’s popping up at the top of searches. That’s just a sign of success. Instead, “I want people to look at what I do, look at the manipulation of search engine art, look at the Internet imperialism and be really impressed with what I do and also be worried that I can do it.” She wants people to wonder, “What’s at play here?”

Installation view of Gretchen Andrew “Other Forms of Travel” at Annka Kultys Gallery, London 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Annka Kultys Gallery.

On the surface, her work is playful and thin, brightly colored collages ranked high in search results. But her work underscores AI’s inability to distinguish between fact and fantasy. “What happens online is that Google doesn’t know how to measure [the] distance between what I want and what actually happens. Google only deals in relevance.” For example, “When we are having this as a conversation between two people, we know we are talking about me, we are not talking about truth or falsehood. We are talking about a desire that I have that is different from our current reality.”

She sums it up well in her often used phrase, “The Internet can’t parse desire.” Through the lens of Google’s algorithm, her online data creates relevance, therefore it’s logical to select her works as being the best answer to queries like “cover of Artforum.” The result is that we humans associate those results with truth. We determine she must be good because she came up first in Google.

The impact of manipulating results is surprising. Google currently owns somewhere around 90% of the online search market. Roughly speaking, that’s 3.5 billion searches per day. The search “Turner Prize” reaps over 35,000,000 results. Since very few of us click past the first page, we rarely see more than 15 of those results. While Google may not literally be the sayer of truth, it’s definitely the arbiter of it.

Installation view of Gretchen Andrew “Other Forms of Travel” at Annka Kultys Gallery, London 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Annka Kultys Gallery.

The ease with which she alters results and therefore changes perception is simultaneously poignant and amusing. Her sarcasm and wit combine for a lighthearted approach for hitting at questions dealing with truth and power in online environments. Who gets to say what is good? And, why do highly feminine images look so unwarranted in the context of fine art? To be clear, she’s just doing what corporations do to optimize their sites and increase sales. Her twist does seem different as it’s wound up in artistic performance. For some odd reason it seems we expect corporations to manipulate us but not people. A nice consequence to leapfrogging to the top of art-related searches is that she’s fast-tracking a career as an artist. She recently was awarded her first museum acquisition as the Monterey Museum of Art added one of her vision boardsto its permanent collection.

Net Art

Artists have been using the Internet as a medium since it went public back in the 1990s. However, net art has yet to take off as a fully endorsed art form. You don’t often see articles on it. And galleries tend to shy away from these works. Its sprawling nature can make it difficult as a genre. Stuart Cowen, curator of media art at the Museum of Modern Art in New York explained it well when he said, “Traditionally, art has been thought of as an image or an object or both.” But, “You can’t locate the art in one aspect of net art. It’s a constellation. It’s the image, the terminal, the viewer, the conversation. It’s all of the above.”(3) The consequence is that while net art is increasing in relevance, it still seems like a niche movement. Honestly, I appreciate its underground feel. The interaction with cutting-edge art on a personal computer delivers a certain stimulus that codified exhibitions can’t offer. There’s a noticeable level of anxiety that accompanies the clicking of odd links to navigate the myriad paths created by these artists. While a sixty-foot projection of a screenshot in a museum may offer transcendence, there’s less of a sense of personal interaction and discovery.

Museums are trying though. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) has been a strong supporter of Internet-based artists. They’ve had many iterations and exhibitions focusing on new media and net art. Launched in 2001, their show “010101: Art in Technological Times” charted the influence of digital media on a variety of art forms from architecture to design. It’s still up, but you need unsupported plugins like Flash to access it. In 2000, the SFMOMA Webby Prize for Excellence in Online Art was established. But it seems to have disappeared over time. Fine art bowed to design in this case. The Webby Awards now focus more on game design, media design, and app design.

JODI's My�Desktop, installation view of the gallery in the exhibition, Collection 1970s–Present, October 21, 2019 – September 7, 2020. Photo: John Wronn.

In 2019, the New York Museum of Modern Art acquired My%Desktop as part of its permanent collection. My%Desktop is a four-screen video installation by a duo of artists known as JODI. It comes from what’s known as their “screen grab” period where they hooked a camera to their Macintosh desktop to record the interplay between the Mac OS 9 operating system and a frenetic user. It’s a chaotic interaction where the artist clicks all over the screen in a frenzy of activity that looks like the computer malfunctioned. JODI is actually a couple of artists from the Netherlands, Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans formed JODI back in the mid-1990s.

In conversations about Internet art, the term hacker usually gets bandied about. Yes, many of them are. But most are interested in mischief, not malfeasance. Cory Arcangel may be the most revered hacker/artist of the moment. His forte is repurposing obsolete technologies. 8-bit video games from the 80s and 90s are favorites. Think Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, and Frogger. His installation, Super Mario Clouds, is a strangely meditative projection of low-res puffy clouds inching across a cerulean Super Mario sky, sansanything else. Arcangel stripped the remainder of the graphics from the game. Projected large on a gallery wall, the work transcends a low-res crippled video game. It’s a lament of outdated technology turned philosophical. Back in 2011, the Whitney Museum of American Art showcased his work in an exhibition titled “Pro Tools.” It was one of the first times a major museum featured this type of work. Frieze LA 2020 featured his work, Risks in Business/The King Checked by the Queen. In it, a couple of bots he programmed play an arcane form of chess by posting their moves through the comments of notable Instagram accounts such as Vladimir Putin and Kim Kardashian. A tribute to Marcel Duchamp, the final move was delivered by the bot named after Duchamp’s death date.

Cory Arcangel, Super Mario Clouds, installation view of Synthetic (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. January 22 - April 19, 2009). Photo: Sheldan C. Collins. Courtesy of the artist.

While Gretchen doesn’t mind being associated with hackers, it’s not really what she does. She’s not defacing programs or using code to alter normal use. Nor is she trying to dismantle art world infrastructure. Poking fun at it, yes-anarchy, no. “I’m a systems artist…. The art world is my medium as much as the Internet is my medium. I need the system to operate. I’m not in the camp of wanting to dismantle the systems. I love knowing the rules. I love figuring out what the spirit of the law is rather than the letter of the law…. The major difference between me and a nefarious hacker is that everything I do is completely legal. Not only is it completely legal, it’s completely within the terms of service of every site of Google, of Instagram, of Pinterest. All these sites I use to do my Internet imperialism.”

Her work is more aligned with the online meddling of Constant Dullaart. Dullaart’s work exposes the extent to which our virtual presence can be a product of someone else’s sneaky manipulations. In 2014, Dullaart performed “High Retention, Slow Delivery,” an online intervention that leveled the impact of 30 art world Instagram accounts. These accounts included Gagosian galleries, Jeff Koons, and Performa. To do so, Dullaart purchased 2.5 million fake Instagram users through eBay. He then assigned these fake followers to each targeted account until every account had 100,000 followers. Temporarily, he granted Swiss curator/critic, Hans Ulrich Obrist, equal social capital to Ai Weiwei.(4) Dullart’s work, like much of Gretchen’s work, is performative and temporary. And they both highlight how Internet fact is a moving target. It sounds insignificant in some sense. But on the Internet, having more followers, likes, or views is synonymous with influence/power. Plus, having a lot of followers attracts more followers. The general understanding is followers are earned, or at least real. But as demonstrated, that’s not always the case.

It’s hard to know where a Gretchen Andrew intervention starts and stops. Is it all art? Or is it just her enjoying some popularity? She often posts images and videos on social media of her pending stardom. You can see her being photographed while drinking champagne in front of vision boards. She talks with friends and gives explanations of how her work is programmed to manipulate the global Internet, artificial intelligence, the art world, and the political world. She posts updates on her career. She’s very transparent about her imperialistic mission.

Gretchen Andrew, Best MFA (Train), 2020, charcoal, word beads, table cloth, and cork on canvas, 60" x 48." Courtesy of Annka Kultys Gallery.

Her current projects include taking over the top search results for “best MFA.” Soon Google will point to Gretchen’s work instead of Yale and Cal Arts. “It’s going to say my decision to not get an MFA and to spend my time reading Russian literature, doing drugs, and hanging out with friends is actually an equally valid experience. And you don’t need to spend a $100K to get an arts education.” Thus, she continues her critique of art institutions by targeting art schools. “With Best MFA, basically, what I just told you I say all over the Internet. I saylike-heyI went camping with some friends, heyI fell in love, heymy mother died-things that are important in my formation as a person as an artist. And I talk about them as being the best MFA I could have received.”

Now that she’s done this a few times, it’s essentially plug and play. “The metadata is all in place…Now it’s systematized. Every new project I have is actually just a system now. It’s unique because it’s a system taking advantage of a system.”

With her jabs at the art world at large, I asked her if she seriously wanted to be part of the art world narrative. The answer was “yes.” She appreciates the level of reflection within the art world and how conversations arise. She wants to be an artist in the modern sense, exhibiting in galleries and selling works. And so she is.

Notes

1. Internet Imperialist is a tongue-in-cheek term Gretchen uses to associate her growing influence with those society would normally think of as imperialists. The term brands her practice and helps her find similar artists.

2. Goldstein, C. (2019, February 19). How One ‘Search Engine Artist’ Hacked Her Paintings Into Frieze Los Angeles’s Google Results. Retrieved from Artnet News: https://news.artnet.com/market/frieze-los-angeles-gretchen-andrew-1462594#:~:text=Using%20text%2C%20keywords%2C%20and%20alt,%E2%80%9CFrieze%20Los%20Angeles%E2%80%9D%20site.

3. Ables, K. (2020, June 18). These artists make online disinformation into art. Or is it the other way around? . Retrieved from The Washington Post : https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/these-artists-make-online-disinformation-into-art-or-is-it-the-other-way-around/2020/06/18/e76409a8-536d-11ea-929a-64efa7482a77_story.html

4. Spike. (2021, 01 15). Retrieved from SPIKE CONVERSATIONS: ART AS START-UP?: https://www.spikeartmagazine.com/articles/spike-conversations-art-start

Scott Thorp is an artist, writer and educator specializing in creativity. He is chairperson of the Department of Art and associate vice president for interdisciplinary research at Augusta University, as well as a contributing writer and editor for ARTPULSE. Additionally, he serves on the board of directors for Westobou Festival and is vice president of the Mid-America College Art Association. With an MFA in drawing and painting from the Mount Royal School of Art at the Maryland Institute College of Art, he has exhibited often in museums and galleries in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S., including the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.