« Features

Summer Wheat: Deferral of a Vanguard

By Stephen Knudsen

Through analysis of Summer Wheat‘s painting and installations I will argue for the relevance of a refreshed figural expressionism that has both postmodern intertextuality and genuine selfhood. But let’s unpack some baggage first.

There’s been a black cloud over figural expressionist painters ever since Expressionism’s last heyday in the 1980s. In that decade, the critic Robert Hughes and his minions famously criticized Neo-Expressionism as being lightweight because it did not take itself nor its early 20th-century lineage seriously enough.1

And contemporary figural expressionism still catches flack. Consider the excellent Hammer Museum’s “Undiscovered Country” exhibition in 2005. Curator Russell Ferguson surveyed representational painting in contemporary art by assembling works by artists who, as he said, “avoid the potential traps of academic mimeticism and strident expressionism.”2 That wasn’t exactly a vote of confidence for artists attaching to the lineage of Expressionism today.

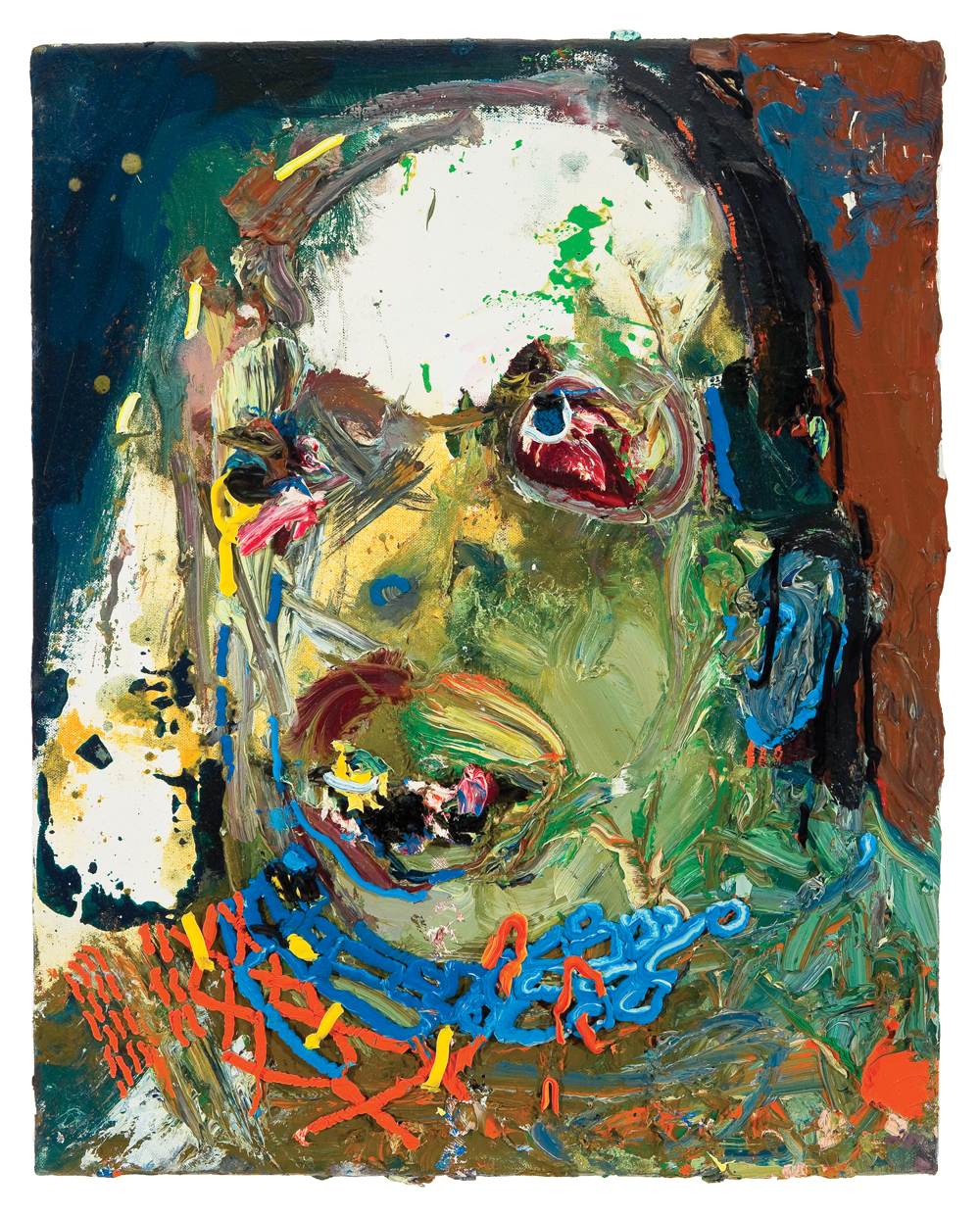

Summer Wheat, Scratchpad (I Believe), 2011, (second version), oil on canvas, 36" x 48.” All images are courtesy of the artist.

But what a difference a decade makes. Perhaps we should not count the expressionists out. This is the age of pluralism after all. Of course, an expressionist like Nicole Eisenman is not going to win big art prizes-like her win of the Carnegie Prize last year-on that kind of any-thing-goes crutch. In my essay on Eisenman in the last issue of ARTPULSE, I briefly mentioned an equally bright talent: Summer Wheat.3 My analysis is fashioned out of two recent interviews and one studio visit with the artist.

The way Summer Wheat talks about her painting is as gutsy as the work itself. It makes someone like me, with a career based on art talk, sit up and take note. Her humor and transparency are welcome antidotes to all easy catchphrases of cultural criticism that grease the hubris of so much of the contemporary art world.

Equipped with her given name, and with a sly Woody Allen smile Wheat mischievously shares: “I was quite possibly conceived on a drug binge in the late 1970s and delivered by a man named Dr. Beavers in Oklahoma City, Okla.” In a memorable academic lecture last year, she opened with some self-psychoanalysis. “Consider my parents. When I was growing up my father was a lovable obsessive neat fanatic. He would carry a little metal ruler in his pocket to measure proper alignment of his shoes in his closet. My mother was a lovable couldn’t-care-less-about neatness freak. The kind who could put her feet up on the table at dinnertime.”

Therein lies the intensity of Wheat’s work and perhaps the intensity of all aesthetically memorable work: tension. Consider what we get when tension is missing, when everything flows in just one direction: Hallmark films, bad acting and art that spoon-feeds ribbons and bows.

Consider the good tension in Wheat’s large-scale 2009 painting, Scratch Pad (I Believe). It has the odd couple of sloppiness and meticulousness that is in all of her work. The socks in this painting epitomize what is at odds: one is carefully striped while the other gets the oh-the-hell-with-it treatment. Thanks, Mom and Dad.

Of course, the tug-of-war between the image and paint guts is an old but still lovable feat when done well. In Scratch Pad, creation is direct and primitive, using recognizable imagery charged with the sting of battle-an electrified aftermath, as if something fast and wild just passed over the surface. Scratch Pad recalls 1960s Bay Area painting without being excessively derivative of painters such as Joan Brown, David Park, Nathan Oliveira and Richard Diebenkorn. Wheat’s work has more Tasmanian Devil in it, with bits and pieces of pigment flying round in narratives far more emotionally charged than Bay Area work. In Scratch Pad, wild streaks of paint animate the room as much as the figure. It is as if the pleasuring is radiating into the walls. Bay Area was funky but never that funky, never in such motion and never so close to being out of control. For its ferocity, Wheat’s work does compare well to Willem de Kooning’s Women series of the 1960s.

Wheat lives in Ridgewood, Queens, and works in Bushwick, Brooklyn. She is one of the newcomers to the vanguard of 21st-century Expressionism, calling back to the origins of the movement: Edvard Munch, Oscar Kokoschka and German Expressionists Max Beckmann, Emile Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Dix and many others.

Like her forebearers, Wheat has painting-from-the-deltoid fluency in her work. Bed of Roses, for example, has breezy athleticism built into the line, complexity and detail. It is as fresh and as good as the best of the Austrian Expressionist Oscar Kokoschka. Think of his 1913/14 The Bride of the Wind.

Wheat’s formal skills are more than strong enough to take on old-fashioned expressionistic idiosyncrasy: soul-baring, reckoning with absurdity, acknowledging the joy, pain, embarrassment and ecstasy of being human. Wheat is Expressionism’s new heir, but she is not alone on the front line in Expressionism’s sincere resurgence, which includes painters with similar wit and expressionistic bent: Nicole Eisenman, Dana Schutz, Natalie Frank, Trenton Doyle Hancock, Matt Blackwell, Judith Linahares, Natalya Laskis, Greg Eltringham, Robert Barnes, David Humphrey, Helen Verhoeven, Harumi Abe, Paula Rego and the Cynical Realists in China.

Wheat spent a decade in Savannah, Ga., where the idiosyncratic Gothic South (as depicted in John Berendt’s famous Savannah-based nonfiction novel)4 converges with a 12,000-student art school. She earned her MFA at Savannah College of Art and Design and became a productive full-time painter for several more years until her move to Brooklyn in 2009. In the Savannah period, Wheat has noted that she “lived discreetly in seclusion for nearly seven years in order to deeply investigate and develop [her] own way of doing things with painting, drawing, and sculpture.”

In Savannah, she met a woman who worked for minimum wage at a trolley tour office. Her husband worked two backbreaking factory jobs-a night and a day shift. Every morning at 3:45, the woman would draw a bath for her husband. When he arrived, she would wrap his swollen feet in hot towels. A number of paintings, including Bed of Roses and Lunch Box, take up this narrative.

Wheat makes sociopolitical critique through empathetic tropes. We know the combined wealth of the world’s poorest segment, three billion people, is equal to the wealth held by the world’s richest 300 people (few enough to fit on one 747). So what does Wheat do with that? She tells a love story.

Critic Sarah Lippick said it best in describing the 2012 It Was The Best of Times exhibition. “This is love as toil, stretched beyond the limits of sacrifice. When there is nothing more to give, the body finds more. Summer Wheat’s assertion is that we are made of our toils, marked irretrievably. The horizon of her sympathy extends even to objects, to the curled and battered toothpaste tube imprinted with fingermarks where it was squeezed, but she explicitly attends to the human body and its scars. The knuckles battered in the ring or the kitchen or the fields, the form misshapen by collision and demand. Her materiality is grimy, lumpen, she smears paint wantonly, with her bare hands, with rags and broken brush-ends and whatever comes within reach. She and her creations are stained and bruised by this heavy contact. Wheat’s work, however, is not about suffering. Suffering is a mere fact. The contemplation of suffering does not purify, for Wheat, but leads to nothingness, a dead end. It is not suffering that demonstrates love, in the Christian sense, but love that makes suffering possible. Finding more when there is nothing more, giving more than the body has to give.”5

In an earlier body of work, Zombie Series (2010), Wheat took up what high art rarely takes seriously-the base archetype of human darkness-the zombie figure. One would expect the subject matter to be repulsive, as it is in B films and endless zombie art kitsch in the digital commons. But Wheat’s zombies don’t repulse. She says that by “wallowing voluptuously in ugliness, I find a paradoxical serenity and delicacy, even beauty.” The paintings ultimately create a relevant high-low mix because these figures are beautiful, violently painted personifications of confusion, darkness and the fragility of living within the brighter context of serenity and humor. The thick, gutsy play of complementary color merging into muddy passages mirrors what the faces themselves are conveying: chaos and serenity.

Placing the zombie archetype into historical context is a challenge. The undead rarely qualify as subjects of high art. Early Christian resurrection themes are off mark, as are Goya’s mythological paintings, though, if we ignore the title, Saturn Devouring His Son (1819 - 1823) reads perfectly as an undead flesh eater. Magritte’s Woman Eating a Bird (1927) also has potential.

In drawing a line from Wheat, I cannot do better than casting back to the Austrian Expressionist Kokoschka once again. In 1914, Kokoschka’s lover, Alma Mahler, broke off their turbulent two-year relationship. In his distress and depression, Kokoschka had the bizarre urge to make a detailed, life-sized doll of his ex-lover: an undead resurrection of sorts. Alma would never return, but Kokoschka kept the doll for five years and did a number of paintings of Alma using the doll as a model. He kept another relic, one that he called his child-a blood-stained rag from Alma’s termination of a pregnancy. Wheat’s work features similar supremely awkward scenarios.

The zombie portraits reflect Wheat’s fear and vulnerability at the time, something she has recently come to terms with by just putting in the work-a lot of it. She made the portraits just after the nadir of the 2009 worldwide economic meltdown when, she said, “our societal constructs were being pulled and prodded from each other in gruesome ways.”

What keeps us together when our world is falling apart? When Kokoschka’s loss of Alma and WWI converged in the same year? Kokoschka showed stubborn resilience in his work, and so does Wheat. Wheat’s work, like Kokoschka’s, is at times deeply self-referential, but unlike Kokoschka’s, it is almost always derived from empathy. Another Lippick phrase comes to mind: the concern for “class wars, inequity and brutal assignments of fate with no repeal or recourse.” In Wheat’s hands, even the iconic zombie is built this way.

The zombie portraits are more than merely grim. Like all of Wheat’s work, they contain what she calls “internal crossfires,” messy contradictions ranging from “That is just wrong” to “I can kind of accept that.” There is something lovable and humorous in these zombie portraits-like the lovable zombies in Michael Jackson’s iconic 1983 music video, Thriller. If zombies can dance, why not have them pose for portraits?

Wheat’s gallows humor makes her work more than just a rehash of Austrian Expressionism. Kokoschka and cohorts were just not that funny. Wheat defies the argument that earnest Expressionism has nothing relevant to add to contemporary aesthetics. Consider a 2012 work, Mud Room, a piece depicting an imagined view of what lies behind the wall in Vermeer’s iconic 17th-century painting The Milk Maid.

Some artistic revivals are more welcome than others. For example, the lineage from Duchamp’s urinal to Koon’s vacuums to Hirst’s sharks seems perfectly acceptable as Neo-Dada working out Dada’s unfinished business. But the passage from Kokoschka to de Kooning to Salle to present-day Expressionists is suspect. Most of the 1980’s Neo-Expressionists, in the U.S. anyway, seemed to prove that there was no unfinished business. The inglorious extraction of good composition and authentic intensity out of Expressionism, as David Salle and Julian Schnabel did, is not exactly the fulfillment of something deferred. It is yet to be seen if the current show of 21st-century paintings by Schnabel at the Dallas Contemporary (through August 10, 2014) will rise above what the museum was careful not to mention in the press release: Neo-Expressionism.

In contrast, Wheat’s work is good enough to square with a more admirable and serious kind of return. In Hal Foster’s brilliant book Return of the Real, “return” refers to Freud’s return as per deferred action, or nachtraglichkeit. Foster was among the first to apply this fundamental psychoanalytic concept to a historical construct.6 As Neo-Dada fulfills the deferred action of Dada, Newman’s monochromes fulfill the deferred action of Malevich’s monochromes.7 In her text Uncommon Goods, theorist Jaimey Hamilton Faris makes the case that Duchamp’s ready-mades advanced the ontological question of art, and that ready-mades in the Neo-Avant-Garde advance the ready-mades’ unfinished business: questioning the commodity’s ontological condition.8

Foster does not mention Expressionism in his arguments on deferred action, and he may be happy to leave me out on that limb. But Wheat’s work does fulfill a deferred action by adding a postmodern edge to Expressionism while still taking itself seriously.

For example, Wheat is all about transhistorical unfinished business. Consider again Vermeer’s painting The Milk Maid. Wheat asks, “Who exactly was that woman in the painting and how much of her toil and suffering is hidden? What if I uncover it?” Wheat adds her own quirky and empathetic response to the essence of Vermeer’s toiling woman.

And with Mud Room, Wheat, in a tongue-in-cheek reverse readymade, finishes Expressionism’s work by letting it spill from the two dimensional onto the floor. The paint (poured into and cast from molds) manifests into actual objects.

Summer Wheat, installation detail of “Everything Under the Sun: Moon and Stars,” 2014, at Gallery Pocket Utopia, NY. Courtesy of the artist and Pocket Utopia.

In her 2012 exhibition Few and Far Between, she paired the installation with Star Chamber. Seven dinner “stations,” or place settings (on the floor), signify high-class stars with the power and money to shape culture and bend the will of others. The piece speaks to the uneven distribution of consumer wealth, power and stardom.

This brings us to Wheat’s current 2014 work, two exhibitions sharing the same title: “Everything Under the Sun: Moon and Stars” at Pocket Utopia gallery, New York, (through April 13, 2014 ) and its sequel exhibit, in production when I visited Wheat’s studio. 9

“Everything Under the Sun: Moon and Stars” is a gargantuan expansion of a narrative started with Mud Room, 2012. In “Everything Under the Sun: Moon and Stars,” Wheat takes Vermeer’s milkmaid completely “out of servitude” and constructs the entire imagined room, opulent and rich, on the other side of the wall in Vermeer’s painting. In this room, the maid takes ownership of a new, higher sociological position. In the sequel to “Everything Under the Sun: Moon and Stars,” the maid’s position ascends even higher to the condition that levels all social and economic disparity: death. The maid, now elevated to a princess, is given a tomb worthy of Cleopatra.

Wheat’s installations are out of control, obsessive, beautiful and a little messed up. Thank God for a little not-rightness and the messy philosophy built into this work: Are there parallel worlds? Why am I me and not someone else, somewhere else?

Ultimately, “Everything Under the Sun: Moon and Stars” does not elicit a cooked-up explanation tugging at one’s existential stance. Rather, it offers the experience of just being in rooms assembled floor-to-ceiling out of tens of thousands of objects made of paint cast in molds: every shoe, rug, tile and trinket. It is an admirable stew of morphing pigment akin to a Pierre Bonnard painting. And like a Bonnard, the edges blur, dissipate and what emerges is essentially a multitudinous array of color-ephemeral and ethereal. The work also transforms daylight into vivid sacred energy. It evokes the color of Abbot Suger, the first to put stained-glass windows in cathedrals.

Wheat’s color language suggests the moving from one state into another. All great existential questions come down to transience and transformation-moving, incarnating, changing. Science comes down to this as well. The trillion assemblies and the trillion entropies, all multiplied by trillions. Human angst, love, sex and death entangle with the puzzling thermodynamics of the universe.

And that is Summer Wheat’s work: the scope, the humanity, the empathy. Of course, those things should be expressed in work that is both messed up and measured out with a little metal ruler.

NOTES

1. Boynton, Robert S., “The Lives of Robert Hughes”, May 12, 1997 The New Yorker. In December 2013 I confirmed via email with Boynton that he directly quoted Robert Hughes via an interview for this article. From the following quote I make my paraphrase: “I don’t like art that thinks it is enough to quote the high achievements of the past-that pretends to be heavy and then takes itself lightly. It merely puts you in a kind of free-floating zone.”

2. Ferguson, Russell, The Undiscovered Country. Los Angeles: Hammer Museum and University of California, 2005 p. 20. Ferguson directed this remark at the inclusion of Fairfield Porter in the exhibit and thus implied the curatorial reasoning for the whole exhibition.

3. Summer Wheat quotes are from my series of 2013 and 2014 interviews including a studio visit with the artist.

4. Berendt, John, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. New York: Random House, 7th edition, 1994.

5. Lippick, Sarah, Press release text for It Was the Best of Times, October - November 2012, Valentine Gallery, Queens, N.Y.

6. This idea comes from my discussions with Dr. George Smith, president of the Institute of Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts (IDSVA).

7. Foster, Hal, The Return of the Real. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996.

8. Hamilton-Faris, Jaimey, Uncommon Goods. Chicago: Intellect Books, 2013.

9. Summer Wheat: Everything Under the Sun: Moon and Stars. Pocket Utopia, N.Y., March 16 - April 13, 2014.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.