« Editor's Picks, Features

The Enchanted Mystery of the Art of Markus Lüpertz

The paintings of Markus Lüpertz present us with doors of possibility, the sheer scale of which begs one to fall in. But you have to approach these works with visceral openness, the way you would approach a new lover. You enter a painter’s world that challenges description beyond Neo-Expressionism, incorporating the classical and abstract to challenge the simplicity of shape, form, color and composition within a language of ambiguity and contradiction that leaves you immersed in the enigmatic and paradoxical. Lüpertz’s works are those by an artistic voice that has been beaten into the canvas in gorgeous, muddy violence built on questions-as if painting was a question itself. The work has a regard for the sacred akin to that found in the theater of Kantor, the compositions of Rachmaninoff and Franciscan theology. Welcome to the world of Markus Lüpertz.

The paintings of Markus Lüpertz present us with doors of possibility, the sheer scale of which begs one to fall in. But you have to approach these works with visceral openness, the way you would approach a new lover. You enter a painter’s world that challenges description beyond Neo-Expressionism, incorporating the classical and abstract to challenge the simplicity of shape, form, color and composition within a language of ambiguity and contradiction that leaves you immersed in the enigmatic and paradoxical. Lüpertz’s works are those by an artistic voice that has been beaten into the canvas in gorgeous, muddy violence built on questions-as if painting was a question itself. The work has a regard for the sacred akin to that found in the theater of Kantor, the compositions of Rachmaninoff and Franciscan theology. Welcome to the world of Markus Lüpertz.

A principal protagonist and neo-expressionist of the post-1945 generation of artists, Lüpertz is of significant importance, along with other artistic giants such as Gerhard Richter, Georg Baselitz, A.R. Penck, Sigmar Polke, Blinky Palermo and Imi Knoebel.

His first United States retrospective, now at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., is an in-depth exploration of his groundbreaking paintings from the 1960s and 1970s entitled “Markus Lüpertz: Threads of History.” His second show at The Phillips Collection’s exhibition, also in the nation’s capital, spans the artist’s entire career.

By Daniel Bonnell

Daniel Bonnell - As a renown German artist, your work has been created within a strong culture of fellow European neo-expressionists and sincerely influenced by German philosophers, quite atypical from neo-expressionism in the U.S. The artistic lineages that you protract from are taken seriously so your work is decidedly not ‘put in a kind of free floating zone,’ one that ‘pretends to be heavy and then takes itself lightly.’ (Remarks by the late Robert Hughes pointed at one of the facets of neo-expressionism in the U.S.). To add to the gravity of your work, your two concurrent historic exhibitions, one at the Hirshhorn and the other at the Phillips, deliver an even greater seriousness by virtue of the strength of numbers coming together. How does it feel for you to see all of this work together, and could you talk about some of the sincere seriousness that you regard as primary as you scan over this vast collection?

Markus Lüpertz - I would exclude the American element. Time will tell to what extent America accepts my oeuvre or does not. Furthermore, for me, my exhibitions are a kind of ‘company outing’ where I then encounter those of my paintings again that are in storerooms or in museums. The exhibition setting is a matter of current activities of the day. And if museums are happy to show my stuff then I am grateful, without having any clear expectations of what the public will think.

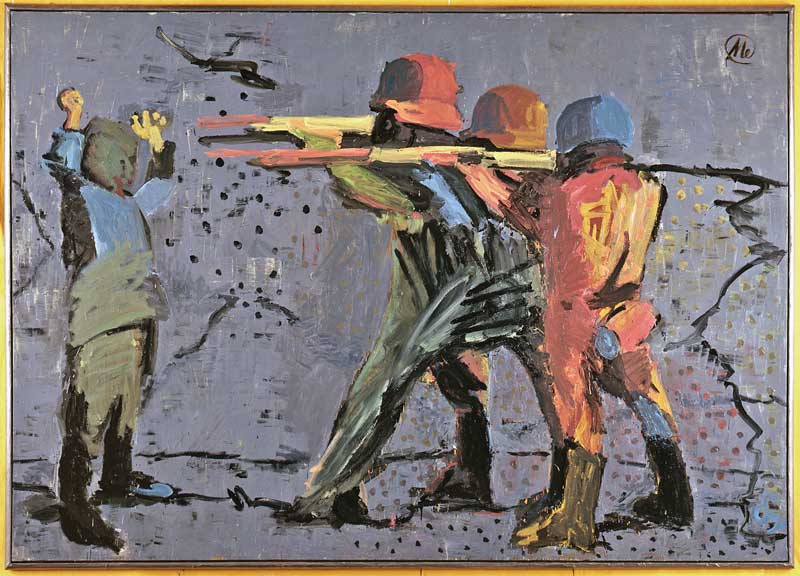

D.B. - Within your huge painting entitled Exekution (1992), (118 by 167 ¼ inches), we see a replay of Goya’s work The Third of May 1808; the central figure being executed in Goya’s piece is a form of Christian iconography depicting a laborer as the crucified Christ. In 1951, Picasso used the same iconic reference in his Massacre in Korea. In your work, you change the symbol of the Christ figure to a hooded man. The emphasis of the work appears to be on the Nazi helmets and uniforms. Your version appears as a piece that is atypical of your other work within its chronological order. Would you unpack some of the significance of this painting for you?

M.L. - The photo on which I based the painting is a photo that strangely touched me. So I researched it and found out that the photo was a staged image made by the American occupying forces, who used the photo to reproduce one aspect of the terror of the Third Reich. I am firmly convinced that the photographer knew the Goya image just as he must have known the Manet one. And it was this strangely artificial quality that so fascinated me, as I do not normally tend to respond to such photos. However, in this special context, the artistic association (Goya, Manet) struck me. And that fascination led to this image.

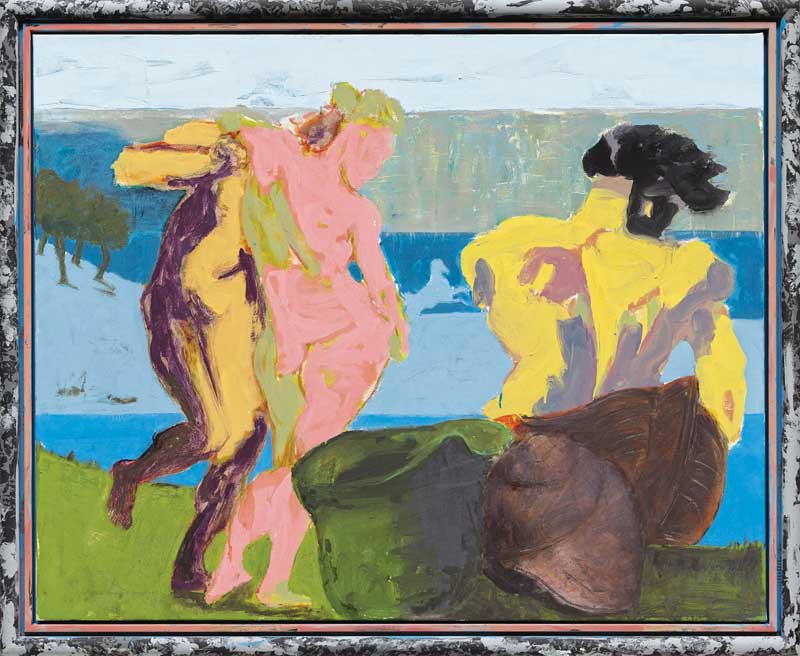

Markus Lüpertz, Arkadien - Der hohe Berg, 2013, mixed media on canvas, 51 ¼” x 63 ¾.” © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy of The Phillips Collection and Galerie Michael Werner, Märkisch Wilmersdorf, Cologne and New York).

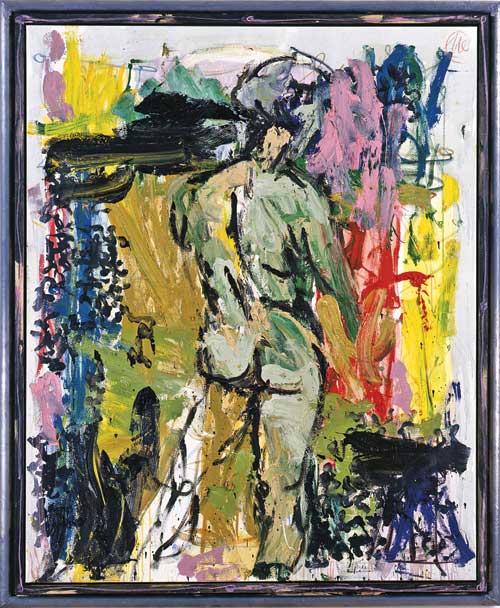

D.B. - The 1960s Bay Area painter David Park had a memorable way of talking of the effect of putting the figure back into abstraction, of marrying the visceral mark with figure. He said it brought the ‘sting’ back to the painting. Do you agree, and would you speak in the context of your painting Nach Mareés - Jongleur mit Rot (2002), as to how your process works to get the visceral energy married to the form?

M.L. - It is true that abstract painting needed to be enriched with a different kind of figuration, as the purely abstract was too limited as it was. Therefore, figures resurfaced in the images, albeit in a much more free and self-confident manner than would have been possible with abstraction. And that is the sensation of our time; namely, that thanks to this phenomenon we have an immense potential of pictorial ideas at our fingertips. I can only congratulate our times and our painters on participating in this new dimension.

Markus Lüpertz, Exekution, 1992, oil on canvas, 118” x 167 ¼.” Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy of Galerie Michael Werner, Märkisch Wilmersdorf, Cologne and New York.

D.B. - You are a practicing Catholic. Many masters, such as Matisse, Chagall, Le Corbusier and Léger, were brought into the Catholic church when they reached their 70s to produce complete houses of worship, windows and more. They were ushered in by a Dominican priest by the name of Père Courtier who had a vision to bring high art back into the church. Would you consider doing the same if approached by the church? If so, what would you seek to envision in a sacred space?

M.L. - I work for the church. I create glass windows and sculptures. I would also welcome murals for religious spaces, but primarily as a challenge on how to tackle the occasion and the space.

D.B. - What do you hold sacred within your work?

M.L. - Let us let religion be religion and painting, painting. Painting is important to me, and religion is my private matter.

D.B. - I understand the needed separation of the two, religion and painting. My question needs to be better worded. Within your processes of creating, do you have a pattern of approaching a painting or sculpture that is sacred, or most important? For instance, do you wait for a non-dualistic inspiration or meditate?

M.L. - My painting is pure reflex. Painting is like watering flowers: Forget it once and the flower dies.

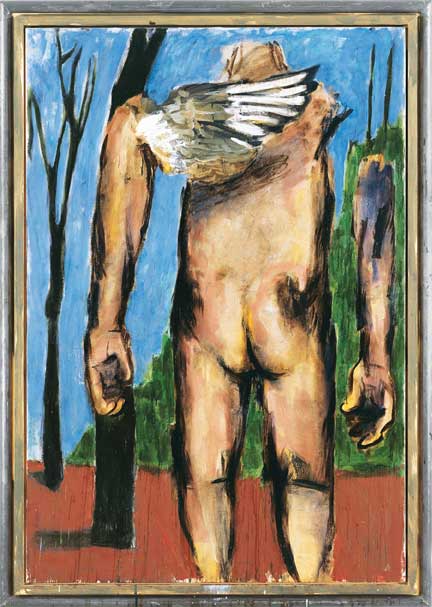

D.B. - I see your work most closely related to Hegel’s hard-to-understand abstract philosophy as he pursued an ultimate synthesis-the absolute idea. Do you approach such an idea in your painting Rückenakt (2006) or your sculpture Athene (2003), whereby you have semiotics couched within the classical?

M.L. - Classical Antiquity is our usual habitat. All our criteria, standards of measurement, notions of form are based on Classical Antiquity, and nothing has changed in this regard. Since there is nothing new in the fine arts, only new artists, the existence of these templates is a permanent challenge-and to this day we define what counts as quality according to these templates.

Markus Lüpertz, Nach Marées - Jongleur mit Rot, 2002, oil on canvas, 78 ¾” x 63 ¾.” Private collection. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy of Galerie Michael Werner, Märkisch Wilmersdorf, Cologne and New York.

D.B. - A Nazi helmet, shovel, skeleton and nude figures regale Ohne Titel (2008). A blue sky or moon is revealed, with a lone figure walking off in the distance. A cut-out style profile of a person floats in the corner. I have read all I can about this painting, but no one appears to make an interpretation. There is a narrative taking place in this work that appears to be tragically beautiful. Could this beauty reflect the pursuit of sehnsucht, that is, deep emotional longing?

M.L. - Each image is a stage, and the mood it conveys is intentional, meaning your sensation is the artist’s intention. Moreover, the attempt by contemporaries to try and explain images is pointless. And only in terms of how it is seen today can we perceive the enthusiasm for an image about faith. Faith is the most beautiful and purest form of addressing painting.

D.B. - Could you expound upon how faith is the most beautiful and purest form of addressing painting? I understand the statement from a perspective of sehnsucht, as a thirst for something beyond ourselves, a faith of hope and desire that cannot be verbalized. Your statement, I feel, is too important to not unpack. Even the statement is its own form of beautiful sehnsucht.

M.L. - Faith, for me, is the only way to approach, to understand, the artworks of living paintings because grasping something disturbs the atmosphere and amounts to a caesura, for understanding always also means disenchanting. And painting is, after all, the mystery in the time in which it occurs.

Markus Lüpertz, Rückenakt, 2006, oil on canvas, 74 ¾” x 51 ¼.” Essl Collection. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy of Galerie Michael Werner, Märkisch Wilmersdorf, Cologne and New York.

D.B. - What is the art that has influenced you most?

M.L. - Let’s differentiate first between art and painting. In today’s day and age, the extended concept of art has no qualitative significance any longer. Meaning if we stick with painting, then at quite specific times quite specific painters fire my imagination and influenced me. Moreover, I am in very close contact with contemporary painters, and the criticism of others or their influence on me takes place in this temporal context. That is legitimate. After all, don’t we all want to be the person to paint that one big and important picture of the epoch? And the more people work on it, the better it is for painting. The greater the qualitative influence, the greater your own output.

Markus Lüpertz, Ohne Titel (Untitled), 2008, oil on canvas, 39 ¼” x 32.” Galerie Michael Werner Märkisch Wilmersdorf, Cologne, London and New York © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Image courtesy of The Phillips Collection.

D.B. - Would you share with us an anecdote from your youth that was instrumental in shaping you as an artist?

M.L. - I believe that the Lord decided that for me. I, at any rate, have no conscious memory of it, because as far back as I can recall I wanted to be a painter.

D.B. - You were the head of the Dusseldorf Art Academy for 25 years, one of the major art schools in the world. What is the most important question that you feel art students can ask of themselves?

M.L. - That is a question that as the head of a master class or professor I cannot answer, because I know nothing about youth. I only know myself and my generation and then as the head of the master class formulate offerings based on my own work. There is perhaps one question that people should ask when choosing to attend an academy: Whom do they wish to study under?

D.B. - You built so much of your work upon myth, the human figure and patterns of color forming a statement of respecting a historical past and morphing into a relevant present. Your later works appear to then take the present as a point of departure from the dualistic struggles and contradictions of life to a non-dualistic consciousness, arriving at a more contemplative self-observing space of observing beauty for what it appears to be, such as we see in your painting Rückenakt (2005). I see this arrival in your body of work relating to your transformation of objects such as tents, helmets, the human form, etc. We are then left with the beauty of the object minus the content, embracing paint as paint, color as pure emotion and form as being sensual. My observation leads me then to that of a mindful state in which judgments are doused and all that matters is the moment. Would this be a fair observation of your present works? Have you taken us to the end of aesthetic theory, leaving us to contemplate simplicity-even a Franciscan mindset?

M.L. - I find your beautiful explanation for my paintings quite fascinating. It is without doubt your explanation, and I like it, but I also hope that there are or will be other interpretations, too.

Markus Lüpertz, Der große Löffel (The Large Spoon), 1982, oil on canvas, 78 ¾” x 130.” Museum of Modern Art, New York, Anne and Sid Bass Fund and gift of Agnes Gund, 1986 © 2017 Markus Lüpertz / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Germany. © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. Image courtesy of The Phillips Collection.

D.B. - At age 76, you have journeyed through your own forms of myths and metamorphosis. What is the next level of metamorphosis you can share with us?

M.L. - I am just as curious and fascinated to see what the future brings for me as are you, and I hope that we will both then be enthusiastic about what I achieve.

Daniel Bonnell is an artist, writer, educator and author of the book Shadow Lessons. The text chronicles an artist’s unexpected journey into an inner-city, at-risk, high school culture. He has exhibited his art in a variety of venues, including St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, St. George’s Cathedral in Jerusalem, Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. His eclectic studio instructors included painter Ed Ross, photographer Ansel Adams and designer Milton Glaser.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.