« Features

The Penetrating Epic Poem. A Conversation with Alfredo Jaar

For his retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma in Helsinki, Finland (April 11 - Sept. 7, 2014), Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar paid homage to the late American poet Adrienne Rich by choosing as his epitaph: “Tonight No Poetry Will Serve.” That these words, written by a poet who dedicated her life to raising political and social awareness, are also used by Jaar to reflect upon his life’s work is no small coincidence, for poetry is the fundamental element in his work. In her poem, Rich writes: “Asleep but not oblivious/of the unslept unsleeping/elsewhere.”

This poem, a solemn promise made by Rich to remain awake even while she sleeps, embodies the wakeful vigilance employed by Jaar when representing the social injustices of this world. This borrowing of title lends itself so aptly to Jaar’s work, suggesting both the interconnectivity between artist and author and also alluding to the global implications of seemingly singular catastrophic events that take place “elsewhere”. “No Poetry Will Serve” consisted of a survey of Jaar’s works, totaling 44, from 1974-2014, including a key work of the Rwanda Project, The Silence of Nduwayezu.

But it is not only the poetry of Rich that appears in the work of Jaar. Over the course of his career, Jaar has incorporated lines written by the American poet William Carlos Williams, the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran and the Nigerian author Chinua Achebe into his work. Each of these poets and writers has influenced Jaar as an artist committed to changing the reality of the world, and nowhere is this more evident than in his creation of the Rwanda Project (1994-2000).

On April 6, 1994, genocide began in Rwanda. For 100 days it raged across the country, claiming the lives of almost one million Rwandans. Although the genocide was perpetuated mainly against the Tutsis, moderate Hutus and the indigenous Twa that populated Rwanda also lost their lives in the violence. In August, following in its violent wake, Jaar traveled to this war-torn country to bear witness to the unimaginable violence of the genocide, which is now regarded as one of the greatest failures of humanity in the 20th century.

Alfredo Jaar, The Silence of Nduwayezu, 1997, one million slides, light table, magnifiers, illuminated wall text, overall dimensions variable. Courtesy Galería Oliva Arauna, Madrid, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin and the artist, New York

After returning from Rwanda, a journey he describes as “the most horrific experience of my life,” Jaar questioned the purpose of representing suffering if it only serves as a reminder of what has been done without further contemplation of what can be done. In defiance of what he terms “the barbaric indifference of the world,” Jaar created the Rwanda Project. Executed between the years 1994 and 2000, the Rwanda Project can be regarded as a form of epos, an epic poem dedicated to the Rwandan Genocide, in which the lines from each poem are an elegy to lives that were lost; the words that accompany the photographs and installations are an ekphrastic account of catastrophe, each piece of the project a canto demonstrating the power of visual and written poetry, and the project in its entirety is a poetic lamentation of the suffering of humanity.

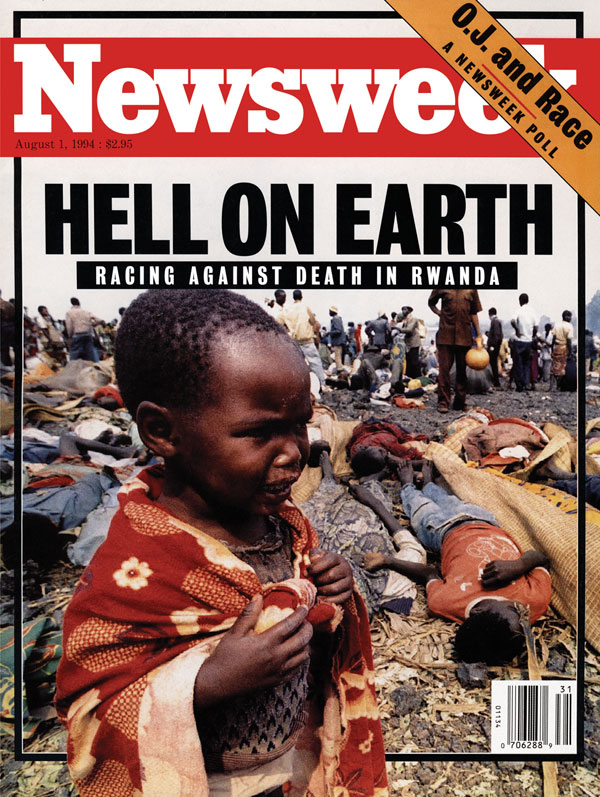

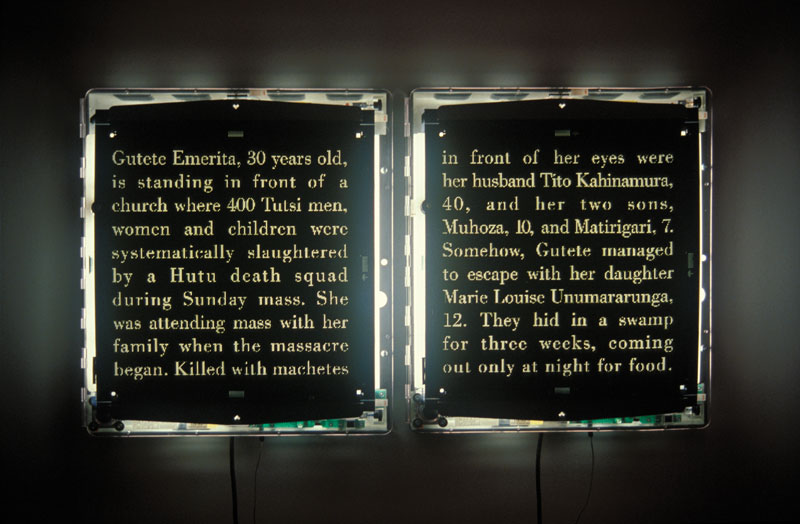

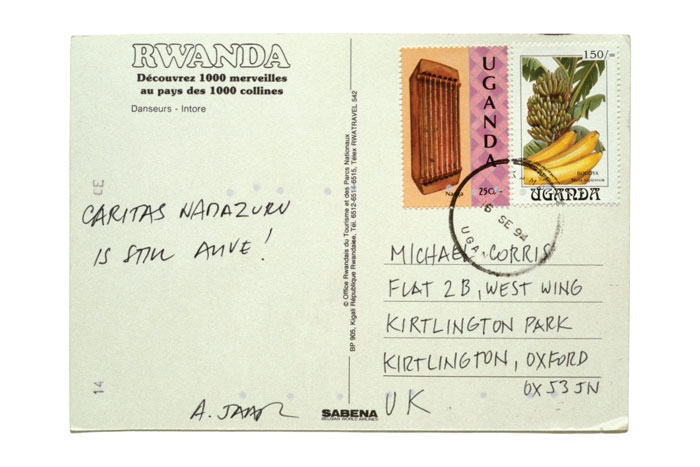

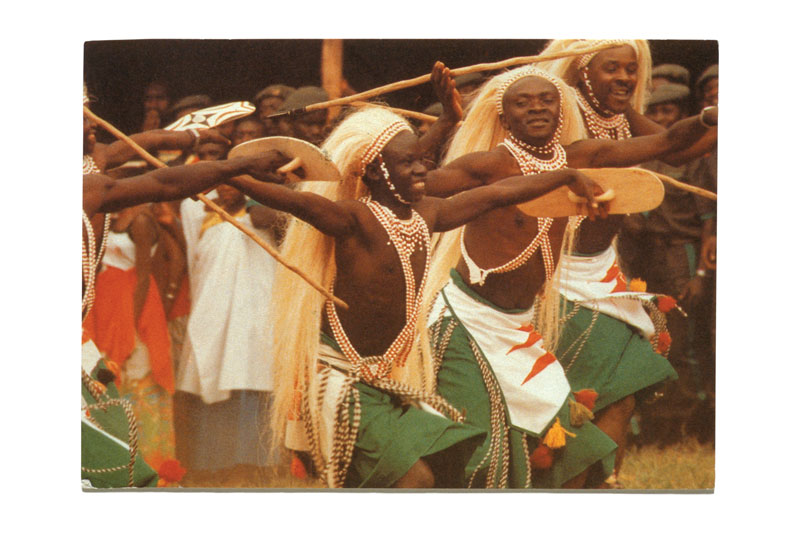

For Jaar, each canto of the Rwanda Project translates a particular moment of the Rwandan Genocide. Whether they are moments of condemnation as found in Untitled (Newsweek), moments of loss, as found in The Eyes of Gutete Emerita, or moments of celebration, as found in Signs of Life, they are all poetic exercises in representation that are at once a dirge and exaltation, an effigy and an elegy, a promulgation and a denunciation of the Rwandan Genocide and the world’s failure to respond to it.

One example of the poetic that is found in the Rwanda Project is The Silence of Nduwayezu, (1997), which consists of a light table, slides, slide magnifiers and a light box with black-and-white transparencies. Within the space of a gallery, viewers are presented with words written in a single line across the wall, where “the public, who had ignored the crimes, have to make their pilgrimage with their eyes on the text.”1 This pilgrimage of text relays the story of Nduwayezu, a five-year-old boy, who watched as the Interhamwe killed his family. In the weeks that followed, Nduwayezu remained silent, refusing to speak of the atrocities that he had witnessed, his silence reflecting the silence of the world.

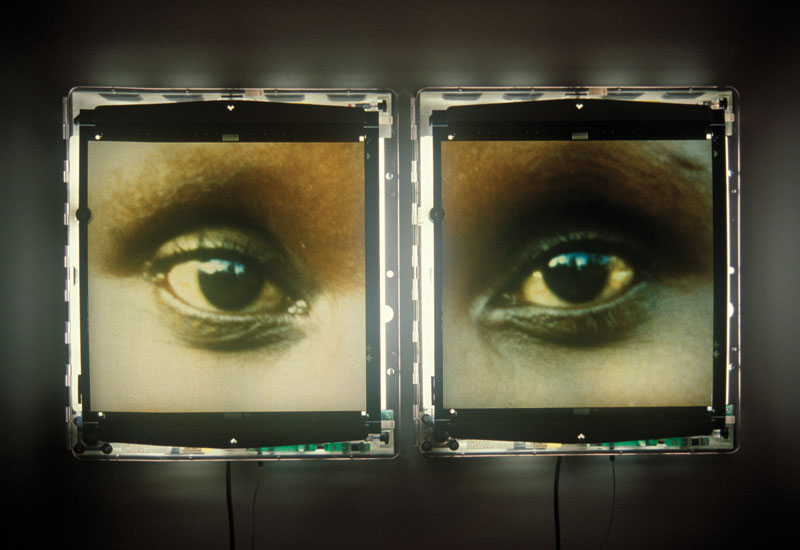

Accompanying the text is a table in the center of the room, where Jaar once again revisits The Eyes of Gutete Emerita to convey the horrors of witnessing. Here, Jaar’s reliance on one image, a single pair of eyes, demonstrates his refusal to use a proliferation of images to portray the unimaginable violence of the genocide. These eyes are an example of Jaar’s use of litotes throughout the Rwanda Project, in which the eyes of Gutete Emerita do not represent her survival but rather are a representation of the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Rwandans over the course of the genocide. They are one million pairs of pleading eyes, asking the world to remember her family, to remember Rwanda, and to remember the genocide that occurred there.

In his awareness of the limitations of photography to portray the suffering of others without further perpetuating their suffering, Jaar’s inclusion of poetry becomes an act of resistance, if not an act of rebellion, against stereotypical representations of the genocide, thereby creating a deeper, more resonant representation of the crimes against humanity that took place. This inclusion of poetry throughout the Rwanda Project reiterates Susan Sontag’s observation that, “Literature can train, and exercise, our ability to weep for those who are not us.” Through words, often present, and images, sometimes absent, Jaar relays the stories of the Rwandan Genocide with compassion and conviction, allowing the viewer to respond with indignation to the violence and weep for the victims, survivors and even the perpetrators of this crime against humanity.

Whereas Jaar often regards the Rwanda Project as a failure, it must be viewed as a success due to the incorporation of visual and textual poetry into each canto. For poetry, whether in the form of words or images, conveys the contrasts and contradictions of the human experience: hope and despair, joy and sorrow, light and darkness, life and death. Throughout the Rwanda Project, Jaar’s skillful combination of these poetic and all too human elements ensures that the tragedy of the Rwandan Genocide will not soon be forgotten.

On the 20th anniversary of the beginning of this infamous moment in time I sat down with Jaar to discuss his Rwanda Project. Though his work has been discussed at length elsewhere I wanted to get new insights into his use of the poetic in that work. This interview dovetails with my two-month research trip to Rwanda in 2014.

Briana Gervat - Scholars often describe your work as poetic. Is this something that is important to you? If so, would you regard the Rwanda Project as an epic poem?

Alfredo Jaar - Poetry is fundamental for me and it is always a fundamental element of my work. What I try to do is strike the right balance, or the perfect balance, which is something that is very difficult to do, between information and poetry. When the work falls into the information category and there is not enough poetry, I think it becomes like the news: It is not interesting and it is not really a work of art. When it falls on the side of poetry sometimes it is too beautiful or too sweet and people dismiss it because it has no content. So, it is very difficult to balance these two: the content, which is the information with all of the educational aspects, and the aesthetic part, which is the poetic component. When those two are balanced you get, in my view–this is very personal–the perfect work of art.

Alfredo Jaar, Untitled (Newsweek), 1994, seventeen pigment prints, 19" x 13", each. Courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg / Cape Town, Galerie Lelong, New York, kamel mennour, Paris, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin, and the artist, New York

B.G. - In interviews you have said you read newspapers with your father as a child. Did he also have you read poetry?

A.J. - No. My father was obsessed with reading newspapers, and he could not go out into the world without seeing these papers. He had to know what was going on in the world before going out. Since then, reading the newspapers and being informed has been very important for me, and I have always said that for me it is fundamental to understand the world before acting in the world. It has become my modus operandi. And so the news element was always present from the beginning, and thus the first works that I created, I felt, were too didactic. They were too direct, and I felt the need to incorporate this aesthetic element and to force myself to balance those two, so that is when I started to incorporate poetry. And when we say poetry, it is visual poetry, and sometimes it might be written poetry but it is always visual poetry, and that has been a very long process where I learn how to balance the ethics. The balance is in the content, it is in the information, in the news aspect of the work, and the aesthetic is in the visual poetry of the work.

B.G. - You have said that you found it difficult to use the images that you collected in Rwanda. Is that why you reverted to using pieces of the news in the Rwanda Project? Is that why you use text and literature in your work, just in case you are not able to convey the poetic?

A.J. - During those six years I created more than 20 works and each one was an exercise, and each exercise had an objective. As I went along, and I could not stop making this exercise because I felt I was failing to convey what I wanted to convey, I kept going. The first works dealt with the indifference of the media, what I call the barbaric indifference of the world media. I wanted to inform people and to do it in a way so to move them into action. So, as to the Newsweek piece, I am not sure there is much poetry in there. It was brutal denunciation. What is most interesting for me is that I do not add anything to those covers, and underneath those covers I try to give a timeline on what was happening in Rwanda and try to get them to understand why I am showing them these covers. The typical reaction was, ‘Did you fake these covers? Are they real?’ They could not believe that for 17 weeks there was no reporting on these covers on the Rwandan tragedy. I am not sure there is a poetic component, but perhaps I am trying to suggest some poetic justice by incorporating the timeline next to the covers.

Detail from Untitled (Newsweek), 1994. August 1, 1994: Newsweek magazine dedicates its first cover to Rwanda.

B.G. - You have dedicated over 10 years to this endeavor. Will this continue to be a lifelong project?

A.J. - I don’t think so. It was very difficult to work on it. It took a personal toll, and it was difficult to stop and it was difficult to get out. And so the fear of going back to it would be that I would not be able to get out. I was invited back to create a memorial for the people of Rwanda and then the funding fell. Perhaps this would be one reason to go back to it, if they call and say they found the funding, then let’s build it; then, of course, I will go back to it because this memorial is very beautiful. There are no traces of what happened, it is a very poetic ending to my work. It would be the perfect ending if it is realized.

B.G. - Do you see the Rwanda Project as representative of the grieving process?

A.J. - I normally feel very uncomfortable speaking about this because what I experienced was nothing compared to what I witnessed other people experiencing. The trauma of genocide, death and displacement was such an immense, horrific tragedy.

B.G. - In interviews you often speak of those that you admire. Can you tell me what poem or poet has had the greatest influence on your work?

A.J. - The entry to my website has a poem by William Carlos Williams, which is one of the most extraordinary poems ever created.

B.G. - Have you read Adrienne Rich?

A.J. - Absolutely. My next exhibition has the title of one of her poems: ‘Tonight no poetry will serve.’ This is one of the last poems that she wrote before dying.

So, besides these two poets, there is one other Italian poet that I like to mention and his name is Giuseppe Ungaretti. What is important with him is the economy of means in his work because he is able to convey so much with so little. It is almost like a Japanese haiku. The challenge of the haiku is to manage to convey an explosion of meaning with the fewest of words, and this is what I do in my work. All of my work responds to the haiku structure, which means I am trying to convey as much as I can with as little as possible because I do not want to overwhelm the spectator with information. I want to convey the simple idea in the deepest possible way. That requires a lot of editing.

B.G. - Since you do not want to overwhelm the viewer, do the theories of memory and visual trauma play a part in your work?

A.J. - Absolutely. In the Rwanda Project I wanted to offer a comprehensive whole, so each exercise focused on a specific issue, moment or theme within the genocide, and I developed different ideas so as not to repeat myself. I learned, and from what I learned I moved on to the next exercise. So they are installations, they are films, they are projections, etc., so that each one is focusing on a particular aspect of the tragedy that I wanted to convey.

B.G. - You speak of learning as being important in your work. Do you feel that you have taught viewers anything? Have people not only reacted to your work, but also acted because of it?

A.J. - Well, that is part of the objective. The ideal work of art is to inform and to move you to action and to touch you, to illuminate you. Most of the time I failed but this is the ideal-to fill you with sadness and joy.

B.G. - What do you feel is the most poetic force in your work?

A.J. - I am an architect and I am an architect making art, so I use different elements from the language of architecture: space, scale, movement, light, darkness, silence, and I invite the spectator through this maze, this architectural maze that I use as a language. Light is one of these elements because of its enormous potential. Light is necessary; it is the origin of photography, and light has this extraordinary spiritual element, so I end up using a lot of light.

B.G. - You also use darkness. With Emergency, I found that this exercise was the most different of all your exercises. Did people stay to watch the immersion and the submersion of the continent?

A.J. - I am aware of the limited capacity of the audience. Sometimes I provoke that and I say that if you do not see it, that is your problem. They would walk by the center and see this pool. Most of the time the pool was quiet. People will not see it, and I thought that it was the perfect metaphor because it was happening and it was there and they don’t see it. So I liked that. We had a very slow rhythm, as if saying you weren’t aware of what was happening in Rwanda.

B.G. - You often speak of hope. Is there a message of hope in you last Rwandan exercise, Epilogue?

A.J. - Epilogue is a very sad piece too. It is of an 80-year-old woman, Caritas, who walked hundreds of kilometers to escape the tragedy, and she is there in a refugee camp, the largest refugee camp in the world, in Goma. She is looking at the camera and she is dressed very dignified. In this work you have her face fading in, and when you are trying to understand her, to capture her, she fades away. You could not colonize her; you missed her like you missed so many things. It is a fitting image because it comes in and comes out, comes in and comes out, and it becomes air, nothing. It was my very sad epilogue to the project, almost like a farewell. I wanted to remind you of the genocide.

B.G. - Although The Sound of Silence is not an exercise within the Rwanda Project, there are similarities between the messages that you are attempting to convey. Do you believe that project relates to the Rwanda Project?

A.J. - The spirit of that work is similar to the Rwanda Project. It is a theater built for a single image because I wanted to tell a story and I wanted the spectator to dedicate eight minutes to a single story, a single image. It is an homage to photojournalism, to the power of a single image, and that is what I was doing with that piece.

B.G. - You speak of hope and sadness in a way that parallels Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran, to whom you dedicate your project, In Memoramium. Do you find that quote to be indicative of your experiences with the Rwandan Genocide?

A.J. - If I could pick a poetic manifesto, it would be the Cioran quote. This harmony that it expresses between joy and sadness/despair is something that I experience all the time. The despair comes from witnessing the suffering that takes place in this world. At the same time, I hang on to the joy of life. We have sun, we have beauty, we are here, sitting on sofas, we have shoes, and we have food. This is something that is not normal. This is not what the entire world experiences or has the privilege of. I am always perfectly aware of the privilege of my life and my capacity to think and to move around in the world. All of those things give me joy, so I am always aware of all of those privileges that give me joy and at the same time I am aware of moving around the world filled with despair. I have used this poem for 10 years, and I cannot change the entry to my website because this poem says everything that I need to say about my work.

Alfredo Jaar, The Eyes of Gutete Emerita, 1996, two quadvision lightboxes with six b/w text transparencies and two color transparencies. Courtesy the artist, New York.

B.G. - After concentrating on social injustices and the suffering of others over the course of your career, what pushes you forward? What keeps you going?

A.J. - What keeps me going is that this is what we have to do–my work as an artist, I am not a studio artist. The projects are based on the reality around me. It is natural that I do what I do. Chinua Achebe, an author whom I greatly admire, has said, ‘Art is man’s attempt to change the order of reality that has been given to us’ and that is what I do in my work. As an artist I try to change the reality that has been given to me. So it is perfectly natural, in spite of the pain and the suffering and the personal toll, that this is what we have to do. We have no choice. That is living.

B.G. - Did you find that while you were in Rwanda that people were hopeful?

A.J. - They want to turn the page. The country is littered with reminders of things that do not help to turn the page. You will see hundreds of memorials. You are going to see more bones that you have ever seen in your life and they are all visible because Rwandans felt betrayed by the rest of the world, as if no one cared, and almost as if no one believed them. You will see all of these physical demonstrations of the genocide, almost as if it’s being suggested to you, ‘You see, it’s true.’ They want to leave traces. How do you live in this world, surrounded by these signs? They seem quite hopeful, but it is difficult.

B.G. - In Field, Road, Cloud, you reached out to see the landscape. Did you find it necessary to look away from the tragedy?

A.J. - I had to because I could not breathe. When you witness what I did you stop breathing. I was looking for breathing spaces, so my camera took me to the sky, to the trees, to the flowers, and I didn’t even realize I was doing it at the time. I have a collection of flowers from Rwanda that I have never shown.

B.G. - Do you feel that there is hope in giving the people of Rwanda art?

A.J. - We need to do whatever we can to create cultural institutions and to bring creativity and educate people with art and culture.

NOTES

1. Vicenc Altaio, “Land of the Avenging Angel.” Let There Be Light, The Rwanda Project 1994-1998. Barcelona, Spain: Actar, 1998.

Briana Gervat received her M.A. in art history at the Savannah College of Art and Design in March 2014. After graduating, she travelled to Rwanda for two months to continue her research on the Rwandan Genocide and the art of East Africa. She now lives in New York City, where she is writing about life in Rwanda, 20 years later.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.