« Features

Alfredo Jaar: A Model of Thinking

By Scott Thorp

Alfredo Jaar’s view on politics is pointed. “We’re working with the awareness that politics has failed us, that politicians have failed us, that regrettably they’ve transformed politics into junk, that they’ve corrupted it, that they have insulted it [1].” This he revealed in a 2012 conversation with the conceptual artist and his friend, Luis Camnitzer. And for Jaar, the sole weapon for dealing with the failures in politics is deep, methodical thinking.

For 30-plus years now, the Chilean-born artist, architect and filmmaker has made sociopolitical artworks about heavy topics like human suffering, political inequity and the value of culture to society. His works vary greatly in media and approach, but always, there is a clear understanding of the power of images. With this understanding, Jaar creates installations that serve as weapons of change in the cultural arenas he considers “the last remaining spaces of freedom [2].”

Speaking recently during his keynote address as honoree of deFINE ART at the Savannah College of Art and Design, Jaar said he wants people to feel there is a model of thinking in his art. And by “a model of thinking,” he means an intensely deep sense of focus toward illuminating core ethical concerns central to the subjects he tackles. Completed in 2014, his latest installation, Shadows, premiered at SCAD’s Museum of Art during the time of his award. Second in a trilogy of works about the power of a single image, Shadows focuses on one photograph taken a year before revolutionaries overthrew the brutal Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle in the late 1970s.

Alfredo Jaar, Shadows , 2014, mixed media installation, SCAD Museum of Art. Commissioned by the Savannah College of Art and Design with support from the Ford Foundation. Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York. Photo: John McKinnon. Courtesy of SCAD.

Somoza’s repressive family ruled this largest of the Central American countries with iron fists for over 40 years. During the final years of his reign, growing opposition from the Sandinista National Liberation Front and the withdrawal of U.S. support led Somoza to embrace extreme measures to maintain his grip on the country, including torture and extrajudicial killings [3]. During this time of upheaval, 1978 to be exact, acclaimed photojournalist Koen Wessing captured a black-and-white image of two sisters agonizing over the loss of their father. Together, on a grassy hillside along the Pan-American Highway, the two young women wail uncontrollably as their bodies torque in emotional pain. The image is quite raw in its portrayal of suffering. Their father, a farmer, had been pulled from his house that morning, taken five kilometers down the street and shot in the head. Days later, while developing the image, Wessing became overwhelmed and subsequently left the country. “It was just too much,” he said later in an interview [4].

Alfredo Jaar, The Sound of Silence, 2006, wood structure, aluminum, fluorescent tubes, LED lights, flash lights, tripods, video projection (8:00 loop). Software design: Ravi Rajan. Courtesy of the artist and Galería Oliva Arauna, Madrid; Kamel Mennour, Paris; Galerie Lelong, New York and Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin.

This photograph, two sisters grieving over the brutal murder of their father, resides alone in a dark room constructed by the artist. In the form of a large projection and only source of light in the space, the image captures these sisters wailing and writhing in emotion. On such a large scale, approximately 10 feet across, it commands an aesthetic presence rare in photojournalistic images. Over time, the background of the photo begins to fade as the silhouettes of the women become brighter and brighter until they appear to burn off the wall. The white light becomes so intense that it’s painful to view with the naked eye.

Then, everything goes black. All that is apparent is the hollow afterimage of the women. Mounted in the hallways leading in and out of the room are images from Wessing’s contact sheet before and after the chosen photograph. From there, the story can be inferred. No text accompanies the installation.

Whether people understand the backstory or not, the image remains compelling. At full intensity, the silhouettes glow at what seems like millions of lumens, forcing everyone in the room to look away. It’s like looking at the sun. The physical discomfort caused by this illumination is a catalyst awakening deeper reactions from the desensitized gaze with which we too often view horrific truths. A few seconds later, a sense of loss pervades as darkness swallows the room. It’s simple in how it works but multifaceted in its residual effect. The single idea is encapsulated in the title, Shadows.

Jaar is sincere in his passion for justice. He is a revolutionary proselytizing at every opportunity. During his lecture at deFINE ART, he told students, “To be young and not to be a revolutionary is a contradiction, almost biological [5].” Coming after a time a few years back when much of art was full of spectacle and apathy, it’s reassuring to see work with more gravity and empathy. The content of Jaar’s work hangs with you for a while and has you questioning your values. Obviously, some may not like the work, but there is no question about whether the statements he makes are well founded and cogent.

The first in Jaar’s unfinished trilogy, and precursor to Shadows, is the much older work, The Sound of Silence. It is one of Jaar’s most sought after works-shown often in museums worldwide. It also hones in on a solitary photograph taken by a photojournalist. But the image in this case is barely shown. This installation is a clear expression of the artist’s belief that “you do not take a photograph. You make it [6].” Both Shadows and The Sound of Silence lie in a body of work the artist calls The Politics of Images. This is an appropriate title for our time in that we often form opinions from images while taking little consideration of the context in which they were made. We do this even with our heightened awareness of how images can deceive. Common is the misrepresentation of our well-Instagrammed selfies. These portraits taken in our suburban backyards transform even the laziest of homebodies into well-traveled, creative hipsters. The underlying matter for Jaar is that “the media must contextualize properly for us to understand [7].”

The photographer whose image inspired The Sound of Silence is South African Kevin Carter. In 1993, while covering the famine in Sudan, he snapped a picture that is hard to forget. A frail Sudanese toddler, appearing malnourished, is hunched over, resting on her elbows. The child’s head is lowered as though nodding to sleep. Behind the child lurks a large, hooded vulture. It is just the two of them in the photo. The conclusion is easy to draw. It’s hard to look at, and it is hard to look away from. The image won Carter a Pulitzer Prize. But after publication in The New York Times, it set off an avalanche of responses from readers concerned for the little girl. They wanted to know the plight of the child and why the self-serving photographer hadn’t helped the child instead of snapping a photo. Three months after winning his award, Carter committed suicide.

Like Shadows, the work is situated in a rectangular room (more like a big freestanding box) built by the artist. The side opposite the entrance is a brightly illuminated solid wall of white light. The entrance on the other side leads to a dark inner area where an eight-minute video displays white text highlighting moments in the life of the photographer.

To summarize: Carter was a pharmacy school dropout conscripted into the South African Defense Force. He hated being in the service. At one time, he shielded a black waiter against soldiers and was subsequently beaten. He left the army, reenlisted and eventually began working in a camera repair shop. From there, he drifted into photojournalism, where he became known for exposing apartheid and taking risks. At the time of the photo in The Sound of Silence, Carter was sent to cover the famine in Sudan. After shooting dozens of images, he found the girl making her way to a feeding center. Once the vulture landed, he waited for the best photo [8].

Alfredo Jaar, Music (Everything I know I learned the day my son was born), 2013, installation view at Nasher Sculpture Center. Courtesy of the artist.

At this point the text stops, and for a few short seconds the photo shows on the wall and then goes away as a flash of light fills the room. It’s a brief time in the span of the overall video. The photo in comparison to Carter’s life was much shorter. Following the image, more text reveals the remainder of the story, including how Carter had shooed the vulture from the child.

Indeed, Jaar knows what he’s doing. He is a seasoned veteran of the art world. He’s exhibited countless times and been showcased in some of the most prominent museums throughout the world. He’s a Guggenheim Fellow and a MacArthur Fellow. He’s a professional, and he knows how to work an image. As Roberta Smith wrote in her review of The Sound of Silence, “In the end Mr. Jaar does exploit a sensational story, and in shaping it, he manipulates us. Except for its savvy presentation, the piece is like shooting fish in a barrel [9].” But as she also noted, he’s accomplishing more than just that. His works are seamlessly crafted with meticulous attention to detail. In doing so, they appear a little sterile in their presentation, almost corporate looking. But what he sometimes loses in grittiness he makes up for in clarity and focus. Rarely do you notice the level of craft in his work-it’s never an issue. Instead, you take notice of the concept he’s expressing.

Much of Jaar’s work targets the anguish resulting from unfair social and political settings. These include many works about Africa. The Rwandan genocide was a major focus of his for a while. These installations are emotionally draining, but another side of his work demonstrates the positive aspects of inclusion and culture. In these, his cleverness shines through by way of actualizing ulterior motives through the commissions he receives. Once he nimbly convinced a paper mill in Sweden to build a museum for the city in which it resided. He did so by burning its commission to the ground.

Skoghall is a small Swedish town that didn’t exist 30 years ago. It was created to support a paper and pulp mill owned by Stora Enso. According to its website, the Skoghall paper mill produces so much paperboard that one in six beverage cartons throughout the world is constructed of their product. In the process of creating a town, Stora Enso financed public institutions such as churches, schools and a hospital so his workers could enjoy a modern way of life. But it’s a shell of a town. There are no cultural facilities.

In pursuit of a greater cultural presence in their community, the city of Skoghall commissioned Jaar to help. Once he learned the town had no existing spaces for art or culture, he turned down the commission. Instead, he argued for Stora Enso to finance a temporary museum-a Konsthall. They agreed. Jaar’s museum was to be built of paper from the Stora Enso plant. It would be temporary. For the inaugural event, art-related activities would be scheduled. Then on the next day, the building would be destroyed.

The debut was a success. Half the town showed. But as time passed, civic minds changed about the latter part of the installation. They liked their new cultural center and wanted to keep it. Jaar’s underlying gift was one of awareness-of something they never knew they were missing. Once the community became aware, they wanted their museum to stay. On several occasions, Jaar was asked to restrain from the destruction; he stayed resolute and would not acquiesce. The museum was set ablaze as the town watched. The final step in the project came seven years later when the artist got a letter for another commission-a permanent museum for Skoghall.

Selected last year as one of 10 artists to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, Jaar found another opportunity to weave his ulterior genius. The question Jaar asked himself and that became the basis for this installation was different than what you might think. Instead of contemplating what he could do for the museum, he asked what the most generous thing was that an institution could do to celebrate its own anniversary [10].” His answer came as a celebration of birth within the community. This feel-good piece is a personal favorite of mine. His ingenious mind is clearly at play in this work.

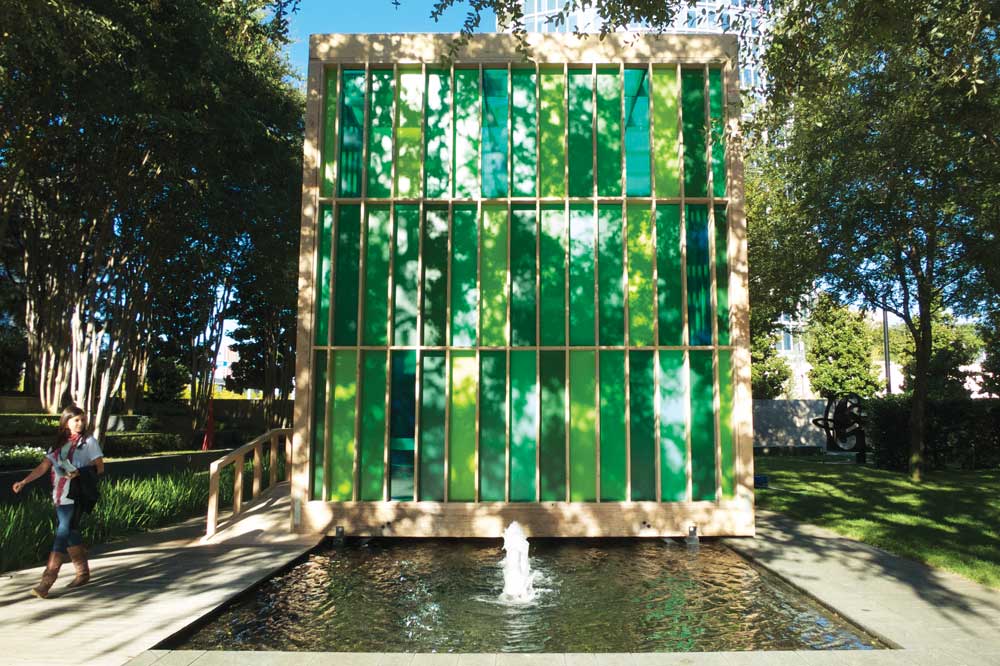

A 21-foot translucent cube sits on top a reflection pool in a tree-filled sculpture garden. Made of colored Plexiglas and wood, its 15 shades of green enable it to hide among the fauna. It’s a place for reflection and celebration. More so, it’s a place of acceptance and integration. The space resembles a stained-glass chapel. From the outside, its calm reflection in the water signifies transcendence.

Alfredo Jaar, Music (Everything I know I learned the day my son was born), 2013, installation view at Nasher Sculpture Center. Courtesy of the artist.

In true Jaar fashion, the added value of Music (Everything I know I learned the day my son was born) lies in its context. As a celebration of birth, visitors to the pavilion are privy to a symphony of newborn cries, each lasting five seconds. Each day you come back, the orchestra grows, as more and more cries are added to the mix. Jaar placed microphones in maternity wards of nearby hospitals-specifically those catering to minority families. Museum membership among minorities is disproportionate from that of non-minorities. While the pavilion exists, the first five seconds of each baby born in those hospitals will be played. And each day those cries will be repeated at the same time. As time passes, more and more babies will be represented, creating an ever more lush composition. The finale of the composition comes as each of the babies whose cries fill the pavilion will grow up as part of the museum. Through Jaar’s model of thinking and the generosity of the Nasher, these babies are being awarded in a novel way by this institution, namely lifetime memberships. Over time, the demographic of the institution will change.

The strength of Jaar’s work often comes from the power of a single idea. Even with much of his art being grand in scope, Jaar’s ability to intensely express one clearly defined concept accords his installations an uncanny ability to impact the viewer. In writing about Jaar, it is difficult to find any of his contemporaries whose work is comparable to his. The most obvious are Joseph Kosuth and Hans Haacke. But in the case of Jaar, artistic comparisons don’t serve much good. He readily states that dealing with the art world is only a third of what he does-the other two thirds being dedicated to public interventions and education. His art is about affecting change, not how it fits in the contemporary scheme of art. But what’s refreshing for me about Jaar’s artwork is that even when dealing with the most horrid of atrocities, it’s not filled with doubt-it’s filled with hope.

NOTES

1. FLUOR, Magazine on Contemporary Culture. Issue #01. January 2012, pp. 8-23.

2. Alfredo Jaar, email interview with author, April 17, 2014.

3. Stanford.edu, “Expressions of Nicaragua,” accessed April 17, 2014, http://www.stanford.edu/group/arts/nicaragua/discovery_eng/timeline/.

4. Alfredo Jaar, “Shadows” (keynote address, deFINE ART, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, Ga., February 19, 2014).

5. Ibid.

6. “Focus On: Alfredo Jaar,” Vogue, November 27, 2013, accessed April 11, 2014, http://www.vogue.it/en/people-are-talking-about/focus-on/2013/11/alfredo-jaar.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Roberta Smith, “One Image of Agony Resonates in Two Lives,” The New York Times, April 14, 2009, accessed April 11, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/15/arts/design/15jaar.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

10. “Focus On: Alfredo Jaar,” Vogue, 2013.

Scott Thorp is an artist and professor at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Specializing in creativity, his book, A Curious Path: Creativity in an Age of Abundance, is to be published late in 2014. His essay “You’ve Got Talent” is forthcoming in the anthology The ART of Critique/Re-imagining Professional Art Criticism and the Art School Critique.

[...] Alredo Jaar is another artist who constantly questions how we view scenarios. Below of an excerpt of an article I wrote on him for ArtPulse Magazine. It deals with one of the most moving photographs of all time. As he shows, things are not always as they seem. The full article can be viewed here. [...]