« Features

Consider This. An Interview with Gregory Coates

For artist Gregory Coates, the definition of painting is never given, and always up for review. Over the last couple of decades, Coates has adopted an ever-growing array of studio practices, embracing a wide range of materials and techniques more traditionally claimed by sculpture, assemblage, and installation. In the following interview, we spoke with him by email about his artistic development, how he selects and uses his materials, his relationship to art history, and his commitment to fostering a more expansive notion of what painting can and should be.

By Jeff Edwards

Jeff Edwards - You consider yourself to be a painter, but your work also has a strong sculptural element that owes a lot to earlier traditions of collage and assemblage. How do you conceive of painting, and how does this affect your choice of materials and the way you use them?

Gregory Coates - Hello Jeff, and thank you for taking time to interview me. I do like to define myself as a painter-mainly because of my need to use color as one of my tools for communication. I like to challenge the notion of what makes a “painting” and so I question the act of painting. Most formal abstract artists use color and paint as subject matter, and create “implied space,” meaning an illusion. For me, the “actual space” as subject matter interests me, so I began to collage more on the surfaces, for example creating line with rubber hoses-actually I am mostly interested in the physicality of the line-and then started to make use of texture, shape and light as subject.

Gregory Coates in Obama, Japan in front of his piece Black Rice, 2010. Courtesy of the artist and N’Namdi Contemporary, Miami.

J.E. - You’ve spent a significant amount of time outside the U.S., including two years of study at the Kunst Akademie in Düsseldorf in the late 1980s, a visit to Capetown, South Africa in 1996, and several stints as Visiting Artist in Residence in the city of Obama, Japan, between 2010 and now. How has studying and working abroad affected your art?

G.C. - I took the opportunity to travel as a way to meet my “peers,” or other professional artists who were sharing similar needs to get out and do shit. As a young person in Germany (Düsseldorf) I was hanging around the Kunst Academy which is in downtown Düsseldorf and subsequently spent time in school there-influences and dialogue there were very much about conceptual art. Beuys was still alive and a presence around the university.

Capetown was interesting in several ways. I had matured as an artist. I was an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem at the time and I was invited to Capetown on the Triangle workshop with European, African and American artists. Two things happened (which would have happened either way, but I made a conscious decision because of it). One, I quit my day job, because everybody there was an artist only (and I was still working as the manager of a nightclub). So, in my mind if these people from Sweden, Holland, Africa can be artists on a full-time basis and be supported, so must I. The other thing was that it reaffirmed my love for used materials and “recycling,” and it put it in more intellectual and socio-political terms. I started out just liking the shape or character some materials brought to the work. But when one of the local African artists asked one of the Dutch artists if he could keep the A-frame house structure the Dutch guy had made, the answer to “what was he was going to do with it?” was “I am going to live in it.” This put things in perspective and reaffirmed that my way of creating from what is there is a good place to be. In short-when you travel you gain insight.

Gregory Coates, Fences, 2011, pvc pipe, rubber, pigment. Courtesy of Verbier 3-D Foundation, Switzerland.

J.E. - I’ve seen the abstract painter Al Loving mentioned in relation to your work, particularly in regard to your gradual transition away from figural painting. What role did he play in your artistic evolution?

G.C. - While living in Williamsburg Brooklyn 1987, still mostly painting with paint, and mostly figurative, I hit the wall and couldn’t make another painting, even though I loved painting with oil and brushes-the feel and the smell of it.

My wife Christiane Nienaber was Al Loving’s studio manager at the time, so I would drop by his 42nd Street studio over the Times Square Boxing Gym. He gave me permission to abandon “the tradition of the brush” as he would put it. Not so much by the example of his own work, but for the fact that he pointed at some assemblage I was playing with as- “that’s your art, man.” What he pointed at and I subsequently discovered was that I needed to not only imply a physical world through painting, but I had to actually use my hands to construct. This was a significant departure into maturity as an artist and permission to do so was granted.

J.E. - Over time you’ve gradually expanded the range of materials you use. For example, around 2007 you added pieces in acrylic paint on feathers to an earlier body of wall-mounted works in plastic-wrapped wood and free-standing installations in stretched rubber. Do you actively seek out new materials to meet certain needs in your work, or just wait for them to find you?

G.C. - That is a very good question, I appreciate your insights. Materials find me.

For example the feathers found me when in 2007 my father-in-law Gerd Nienaber died of ALS and my wife went to Germany to attend his funeral, while I stayed in the USA. During my own grieving, there was this pillow that was given to me. It was a remnant of an art installation by a friend. It had torn and the feathers were going everywhere. I didn’t want to throw it way, because it was once part of someone’s art installation, plus it was a gift. So I took the feathery mess into the studio where I started to adhere them to a surface. This repetitive process helped me grieve the loss of Gerd.

The past was alive in the present and so I made this big feather work, which I painted black. It was very elegant and beautiful and monumental in scale. I titled the work In Memory of … The work was about me and everyone who has shared a loss of someone-and continuum.

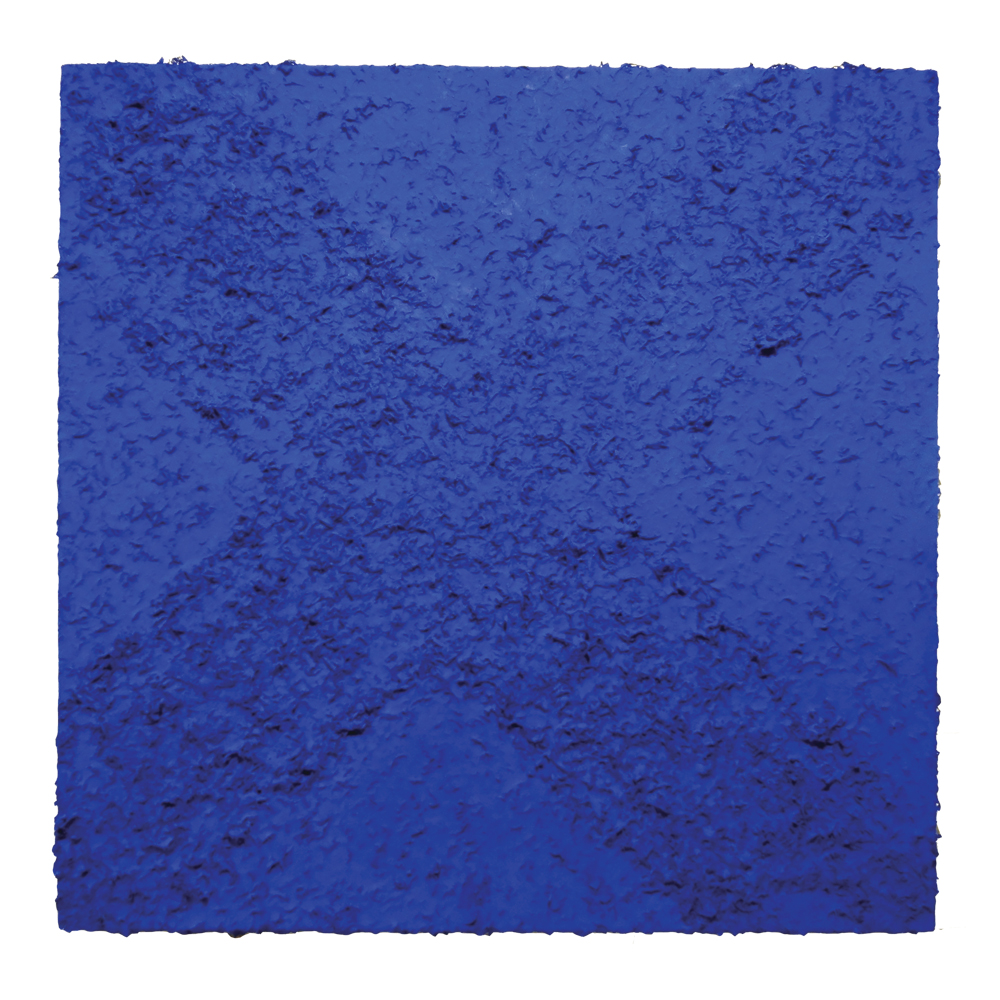

Gregory Coates, My X, 2013, feather, acrylic on board, 72” x 72.” Courtesy of N’Namdi Contemporary, Miami.

J.E. - When you’re working on a particular piece, do you have a preconceived idea of what you’re aiming for? I guess I’m interested here in how much you control your materials or they control you.

G.C. - Well, it’s a balance. (Certainly, I don’t have sketches and try to figure out what a material will want to become.) That’s on a ‘let’s-see-where-it-goes’ basis. I can make a plan about the scale of a piece of work. Though even with that I often work in modules and keep adding on. For me, art is discovered not made. So, one has to work with the tentative notions that there will be something to discover in the process.

J.E. - Color is clearly really important in a lot of your more recent work; it not only alters the surface appearance of your raw materials, but also seems to hint at a wide range of different moods. What are your thoughts on the role of color in your art?

G.C. - I have been using color mostly as seduction. I don’t really think about it. I want the color to seduce the viewer to investigate the materials. So, I guess, I am a color pimp.

J.E. - There are some really interesting formal tensions in your work, too. For one thing, though your works are clearly at home in galleries and museums, you use fragile, streetwise materials that also give them a foothold outside the art world and seem to question the whole idea of art as a precious or archival object. Is that something you think about a lot, or is it just a natural offshoot of the way you work?

G.C. - Damn great insight; I am not into “preaching” with my art or beating up people with my art, but I do want the public to recognize the materials and then enjoy how I subverted or radicalized them. This is important to me. I want to communicate what I consider giving myself “permission” to say to the public, “consider this.”

J.E. - Given the specificity of your materials and the way you use them, comparisons with other artists and art-historical movements seem inevitable. I’ve seen other writers relate your work to Minimalism, Gutai, Art Informel, Yves Klein, Eva Hesse, Jackson Pollock, and Donald Judd, and I think you could also add Lucio Fontana, Alberto Burri, and maybe even Giacometti. How much is this on your mind when you’re working in the studio, and do you prefer some of these comparisons to others?

G.C. - Art History is important to me. I want to add to it. There is a quality and sometimes a signature about some artists, that when applied as a reference to my work I am flattered, even though all is simplified. Like Yves Kline’s blue. I wasn’t thinking about that when I made my first blue (ultramarine) with matte powdery finish. Klein used his blue as subject matter-exploring ways to apply it. I used it “to slow down” the rubber. I don’t think about it, but when I read up on Klein, I discovered I do relate to his thinking more than the “simplification” of “The Blue” would suggest. I like the Fontana reference too. And thank you for throwing Giacometti in there-timeless, complex yet simplified. Tension that holds without stressing (not to mention extremely expensive). Donald Judd, the simple rhythm, the repetition (a big thing in my work)-sure. I don’t reject any of these references, though in general, I don’t think about them unless someone asks me. Personally I just make my art in real time and hope history will be kind to me.

So, I am after making an iconic Coates.

If you see feathers. You should think Coates

If you see ultramarine blue, you should think Klein, or Coates.

Gregory Coates, How Do You Like Me Now, 2006, acrylic on rubber with pvc, installation,12’ x 30.’ Courtesy of N’Namdi Contemporary, Miami.

J.E. - Let’s talk a little about titles and wordplay. Some of your objects have names that imply flamboyant or exaggerated bodily movement-for example, the 2006 pieces Strut, Flounce, and Meander-but they also point out physical features of the works themselves (for example, the plastic-wrap surface of the latter piece, which looks like flowing water and seems to allude to the ancient Meander River in Turkey). Do you think of titles as a way of adding a sense of life or narrative to your works?

G.C. - Yeah. That’s funny…you picked up on the words and use of the double entendre-though most of the time I am not looking so much to add a narrative per se-but an attitude.

Originally the name Strut was given to this big large rubber piece. I like that it was both formal (as in a support) and attitude as in “look at me-I am strutting.”

I liked the title so much I named two shows with it. At Gallery Denkraum in Vienna, Austria, and Magnan Projects in New York (Meander, Flounce and the others were part of the Strut series, pointing towards nuances and individuality in the work. There was another show title I really liked some time ago in New York at Wilmer Jennings Gallery: “Slang” works were named “chill” “flavor” “sprung”… all double meanings. But Slang too is a way of expressing something mundane with attitude and individuality.

Sometimes titles come easy to me, because they are attached to a time and place.

Like Two on a Sofa now in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. It invokes memories of my wife with her sister talking German.

Gregory Coates, Strut (Vienna), 2006, rubber and wood installation, 48” x 150” x 170.” Courtesy of Gallery Denkraum, Vienna, Austria.

J.E. - You’ve also occasionally done short works in video, such as Another Black W(rap) Video (2007), in which two Japanese models engage in a tug of war with a long piece of black plastic wrap that eventually envelops them. How do these relate to your other works, and what are they about?

G.C. - The film was actually made in 2000 (maybe I posted in 2007?). As I have done my share of girl watching, when I was living at the Lower East Side of Manhattan it always struck me that woman like to check each other out. So, I asked two friends of mine and a few of my Cooper Union students to help me with a project, this was Another Black W(rap) Video. This being one of those double entendre titles I really like, which, of course, is about my wrapping with plastic, and the idea of black American culture/music. I thought since I do w(rap)-rubber and plastic,-and I am black, I should make another Black (W)rap video. In so doing, I would, more directly than I would normally do in my other work-defy expectations and stereotypes. I also liked that the video is decidedly quiet. There is no narrative. There is room for interpretation and adaptation of metaphors that I don’t dictate.

J.E. - One of your installations that really seems to want to push the boundaries of painting is Monument to Steve Cannon (2007), in which a rug and couch placed before one of your feather paintings are integral parts of the work. What were you aiming at by expanding the painting toward the viewer in this way, and how does this relate to the way you conceive of your audience’s relationship to your works in general?

G.C. - Steve Cannon is chief of A Gathering of the Tribes magazine and gallery on the Lower East Side. He is blind and would visit my studio at 191 Chrystie St. and he’d make me, and everybody else, tell him what we see. This got me thinking, ‘shit, here is a guy who relies on us to experience the visual world.’ But if I make the work tactile and comfortable, how much more insight would he have? So, yes, in a formal sense I was expanding the sensory to the viewer and wanting the viewer to be in the piece and bringing some of the studio into the gallery. But I was also creating a monument to a man whom I consider an institution, and indicative of great exchanges in art. A Gathering of the Tribes coincidentally maintained the most famous stoop in New York where the likes of David Hammons, Al Loving, Butch Morris (musicians, poets, visual artists) would congregate.

Gregory Coates, Big Black Peace, 2013, feather acrylic on board, 96” x 144.” Courtesy of N’Namdi Contemporary, Miami.

J.E. - Finally, what are you working on now, and where are you exhibiting next?

G.C. - I have more large feather works on the walls, such as what the Smithsonian Institution just adopted into their collection. Collectors seem to respond to the work. I am preparing for two commercial shows-one in Germany. And working on an outdoor piece commission, that to me is quite a challenge in scale and material research.

As a matter of fact, my focus has slightly shifted over the years towards placement and site-specificity of my work. I will be working on a piece at Muhlenberg College, here in Allentown for 2015, that will “fit the square box gallery.” I find myself thinking more about how to activate a space with my work. Another one of those challenges I enjoyed was at the Kamigamo Shrine in Kyoto, Japan, a UNESCO world heritage site, where I was the first artist to “be allowed to create in a shrine.” And I am really proud of the piece I created in Verbier Switzerland. On top of the glacier where the blue pigment covered rubber site-specific installation just sang in the snow during the winter months.

And in the studio, gathering up my “mistakes” as works of art in themselves (boxed up crumpled drawings). I like these objects to be another icon of my work.

Jeff Edwards is an arts writer and faculty member in the Visual and Critical Studies program at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York. He has an MFA in art criticism and writing from SVA and a master’s degree in public and private management from the Yale School of Management.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.