« Features

Kettle’s Whistle. Back to Square One

There were great expectations last spring when Ruben Östlund’s film The Square was premiered in Cannes. Finally, so it seemed, the contemporary art world would be the recipient of a well-researched, intelligent, and caustic study safely distant from the vapid clichés that have dominated every production on the subject so far. The decision to stage the film in a European, progressive city like Stockholm, in stark contrast with the decadent glitter and glamour normally associated with New York or Paris, was a good sign. This, after all, is the same country that gave us SVT Play’s The Artists in Residence: The Turning Torso Project (2010)-arguably The Spinal Tap of contemporary art. Even the fact that the protagonist was a museum curator contributed an interesting angle to the idea. Would finally the audience be spared from the archetypical depiction of artists as lunatic outcasts operating in a circle of airheads whose main preoccupations are spectacularly out of sync with those in the real world?

Not so. After a promising start, with Danish curator Christian confronted by a journalist about the nonsensical jargon of a press release, and a museum gala where a crowd of patrons and collectors jump on the buffet ignoring the chef’s speech to his chagrin, the film quickly falls into a predictable pattern where contemporary art is once again described as an elitist if pointless activity. There is the museum cleaner who accidentally hits a pile of sand on the floor that is part of an installation, triggering comical questions about what to do with the insurance; the arrogant American artist based on Julian Schnabel (an easy target) who defensively deals with an audience member affected by Tourette syndrome during a public talk; the two young PR agents who display a total disregard of ethical practices for the sake of their campaign going viral; the unbearable domesticated monkey who makes “art”; and finally there is Christian’s stolen smartphone, a subplot designed to lead a representative of society’s liberal and intellectual fringe into the underworld made of beggars, immigrants, and homeless people he claims to defend, but actually doesn’t know anything about. Rumor has it that in order to give realism to the story, Östlund initially considered hiring people exclusively from the art system instead of professional actors. The auditions, however, didn’t go as well as expected (gallerist Marina Schiptjenko is one of the few who made the cut) and the plan was subsequently scrapped to everyone’s relief.

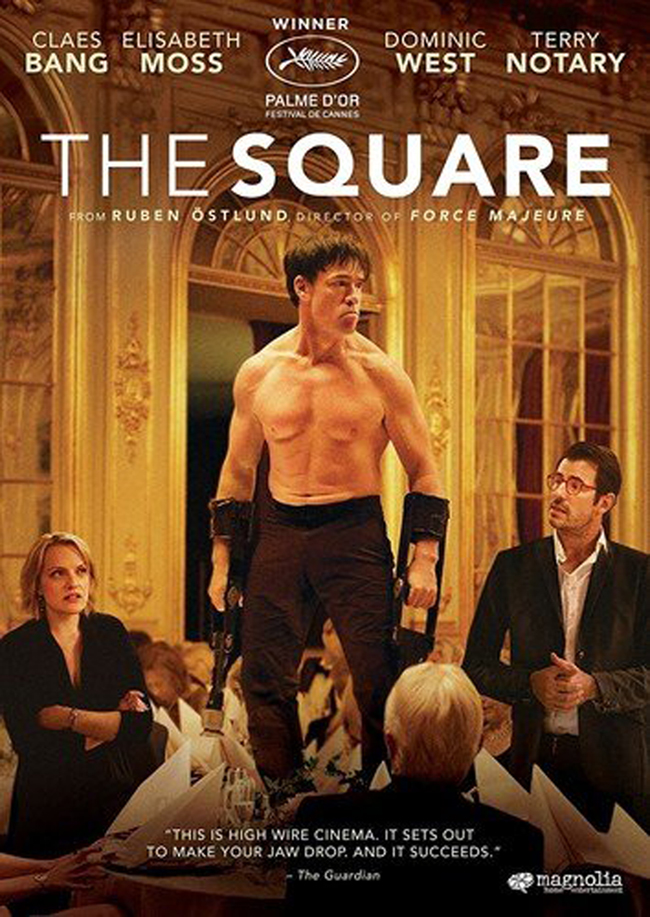

A character often referred to but that remains cleverly unseen in order to maintain the mysterious status of her work is the artist responsible for the piece that titles the film, Latin American Lola Arias. What we get to see instead is Russian artist Oleg Rogozjin’s “ape man” performance, an over the top affair where he physically attacks a group of museum dinner guests eventually causing a riot. The image of actor Terry Notary bare-chested on top of a table has been elected as the poster of the film, which is unfortunate as the scene is probably one of The Square’s major sore points. When Oleg Kulik (the obvious inspiration for the character) performed his barking dog piece in Stockholm in 1996, the political and cultural climate couldn’t have been more different. Russia was going through the painful process or reinventing itself as a free country after the fall of the Soviet Regime. Kulik’s work was a reflection of the anger and confusion of that period, as the title of the exhibition in which he took part, “Interpol: The Art Exhibition Which Divided East and West”, testifies. Another Russian artist, Alexander Brener, would end up in jail only a few months later for spraying the dollar sign over a Malevich’s painting at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Twenty years on, the idea of considering the provocative aspects of these actions resonates in the same way and looks hopelessly out of context, if plain silly. Similarly, Julian’s claim to be a personal friend of Robert Smithson-an event chronologically impossible-asks questions about the director’s knowledge of art and his acceptance of it as a creative discipline that changes and evolves with time. It seems a minor point, but try to imagine a film in our present context where a big aerial cell phone is used instead of a smartphone, or Barack Obama claims to be have been a personal acquaintance of Robert Kennedy, and you get the idea.

Christian’s venture into the slums of Stockholm is a different subject altogether. It goes beyond the contemporary art bubble, and it is a matter of discussion for those who are familiar with the complexities of Swedish modern society. (Although the broken Swedish of the immigrant kid who has a beef with Christian over his tactics to find his lost phone is a universal source of irritation.) Conversely, episodes like Christian’s relationship with his assistant, an area between friendship and professionalism that is grey at best, or the awkwardness between him and the aforementioned journalist after a night of casual sex, are moments of pure brilliance, and indicate that Östlund is much more at home with the dissertation of personal dynamics rather than socio-political analysis.

Contrary to popular belief, the contemporary art world can be prone to self-criticism. There have been many moments in history where artists, curators and writers have tried to highlight the incongruence of its values. A film offering a tart commentary on these issues would be more than welcome. Regrettably, The Square is not it.

Michele Robecchi is a writer and curator based in London. A former managing editor of Flash Art (2001-2004) and senior editor at Contemporary Magazine (2005-2007), he is currently a visiting lecturer at Christie’s Education and an editor at Phaidon Press, where he has edited monographs about Marina Abramović, Francis Alÿs, Jorge Pardo, Stephen Shore and Ai Weiwei.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.