« Features

Christian Marclay: The Evocative Power of Sound

By Michele Robecchi

At home with both high-value and down-home productions, Christian Marclay has established himself over the course of a 30-year career as a pioneer of sound and visual art. Following the success of The Clock, a 24-hour film that took about three years to be completed and is arguably Marclay’s most ambitious work to date, we take a look into the practice of an artist who changed the way we perceive images and music forever.

When Alan Hunter, one of the producers of Alan Parker’s 1981 film Pink Floyd - The Wall, was asked during a U.S. press conference to outline what the upcoming movie was about, he replied “It’s about some mad bastard and this wall, isn’t it.” Such a succinct description of Roger Waters’ legendary opus about alienation and the consequent erection of a metaphorical barrier to strengthen dissociation, coming from a man financially and creatively involved in it, is a testimony at best of how art can rely on gut feelings and doesn’t necessarily have to be rationally understood to be supported, and at worst of how even the greatest masterpiece can suffer from poor judgment when embroiled in a subject close to popular culture, inherently open as it is to shallow interpretations.

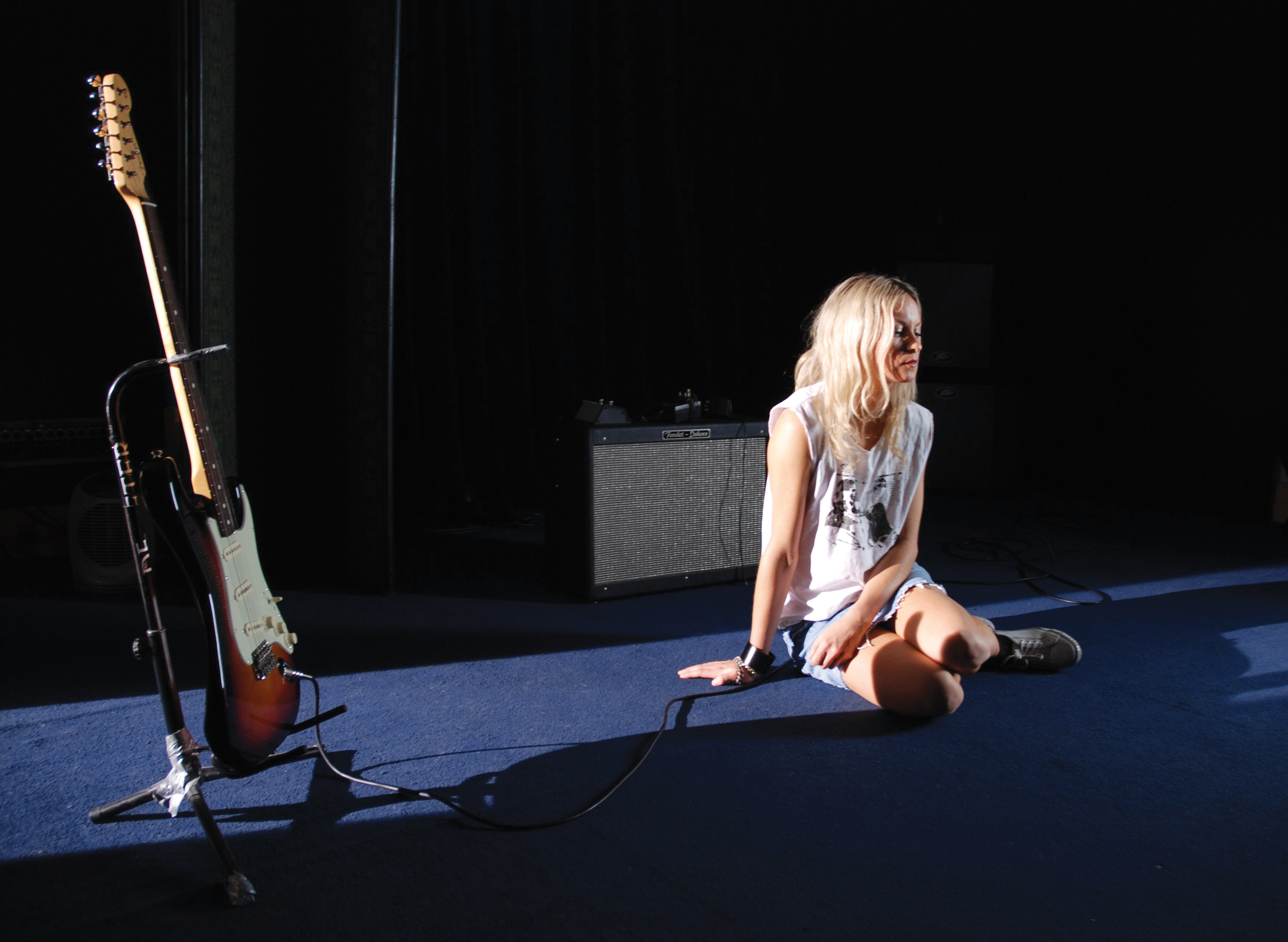

Christian Marclay, Solo, 2008,single channel video / DVD, duration: 17 minutes. © Christian Marclay. Courtesy of White Cube.

It is a mechanism that doesn’t spare either obscure or clear concepts, and one that definitely affected Christian Marclay’s video Solo (2008) when it was presented within the frame of “Unlimited” at Art Basel two years ago. Courtesy of the short attention span that characterizes our times and the dynamics that traditionally inform those events, Solo generated head-scratching responses from a large part of the audience. Earnest, middle-age male collectors would elbow or wink at each other while going in and out of the box, with snappy comments like, “You’re going to love this one,” while some of those who managed to maintain some detachment and genuinely attempted to analyze the film on its artistic merit, would dismiss it as “just a girl playing with herself with a guitar.” As it happens, viewing Solo for its entire duration (17 minutes) would have been enough for people to realize that there is a lot more to it than that. First of all, there is a narrative. The girl in question is seen at the very beginning of the film furtively walking into an empty rehearsing room holding a pair of drumsticks. It is not clear if she is the drummer or the girlfriend of the drummer, but that doesn’t matter. What the drumsticks convey is that the guitar is not her instrument, and that by approaching it she is actually stepping out of bounds to implement a fantasy over somebody else’s possession. Second, she is not “playing with herself with a guitar.” She is making love to it-and how. The passion and lust that possess her in the process are stunning, making it evident that this clandestine rendezvous is the realization of a long-harbored, unexpressed desire. Finally, difficult as this could be, going through Solo with eyes wide shut is a deep sonic experience, a crescendo of strident guitar notes and feedbacks that adds another layer to the rock ‘n’ roll convention of the “guitar solo” and ends up constituting pretty much a work unto its own.

Christian Marclay, Video still from Guitar Drag, 2000 video projection, view #1 running time 14 minutes. © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

This multi-layers (the simultaneous creation of a new sound and a visually powerful image, the tongue-in-cheek revisitation of music clichés, and the representation through a black-box format to enhance its dimensional perception) is nothing new in Marclay’s work and is something that can be recognized in equally strong terms in Guitar Drag (2000), in which dramatically different premises like the brutal, racially motivated murder of James Byrd, Jr., in Texas in 1998, act as the primal connection over a wider variety of links, from the macho rock-music practice of smashing instruments through even some of Roman Signer’s video performances, with this latter aspect as a possible explanation of why some people over the years have been able to detect a humorous note in what should otherwise amount to a rather unsettling experience. Eventually released on vinyl, even if listened to on the most powerful PA system, the soundtrack of Guitar Drag loses some of its grip. Inside the big scale and timeless dimension of the black box, it almost explodes in our body.

Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010, single channel video, duration: 24 hours. © Christian Marclay. Photo: Ben Westoby. Courtesy of White Cube, London and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

The “you have to be there” quality of both Guitar Drag and Solo belong to a side of Marclay’s persona that the fans of his most refined, choreographed pieces, like Telephones (1995), Video Quartet (2002) and The Clock (2010), often tend to overlook, which is the performative ground in which his work is rooted. Contrary to what many people think, Marclay was never the avid record-collector type. His ability to treat so effectively album jackets, vinyl, tapes and CDs as visual materials, like in his early collages The Road to Romance (1992) and Arms and Legs (1992), is precisely due to his detachment to their inner contents. His education in art and music goes back to the New York of the early 1980s, where, parallel to disciples of the pop culture/contemporary art equation initiated by Warhol, such as Jeff Koons, Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman, there was a group of artists rediscovering performance and body art outside the circuit of museums and galleries, culturally closer to the No Wave scene. Although filtered through a punk sensibility, the work of these artists was also heavily indebted to Fluxus, a movement mysteriously underrated in art history, and one from which Marclay has obviously drawn inspiration. This is noticeable especially in Marclay’s sound work and was translated into a tribute to John Cage at Centre George Pompidou in 2010, when Marclay perfectly captured the spirit of Cage’s composition 4′33″ by having artist and writer Louise Stern and her interpreter Olivier Pouliot converting in sign language the noises and movements made by the audience during the execution of the piece. 4′33″, as many have erroneously assumed, is not about silence but about the noise produced by a roomful of people faced with a silent musician. In Marclay’s version, the audience rightfully reclaims a protagonist role, feeding the two performers with their reactions and seeing them dialed back in a circle that breaks the fence between stage and public.

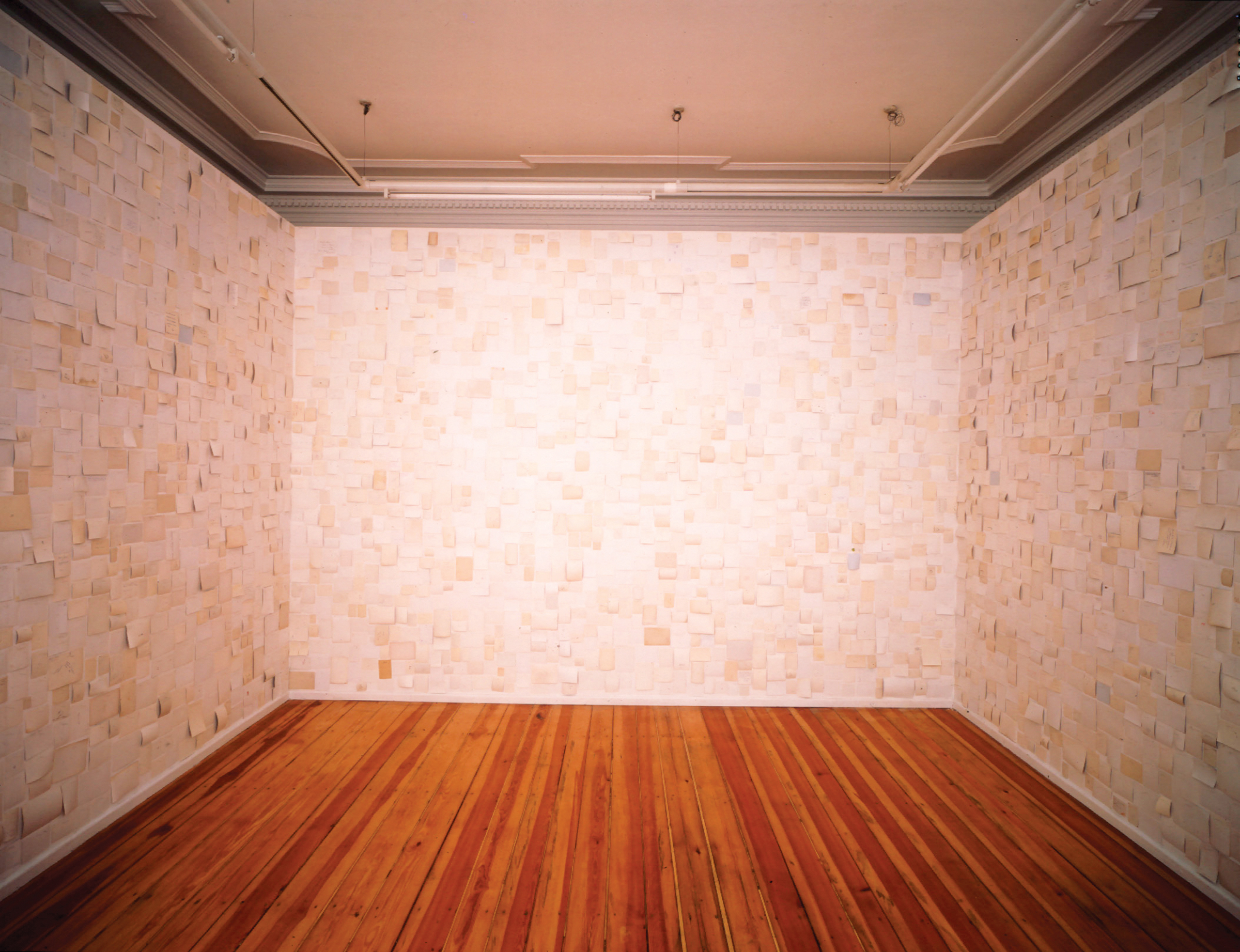

Christian Marclay, Installation view of “White Noise,” Kunsthalle, Bern, May 21 – June 28, 1998. © Christian Marclay. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Marclay’s contribution to “Open Air,” the series organized by BBC 4 in collaboration with Artangel in which visual artists were invited to provide a three-minute sound piece during a time slot normally reserved for commuters, must have left baffled even the most hard-boiled radio listeners. Early morning conversations were suddenly disrupted by classic talk-radio material mixed in deejay fashion, generating a series of interesting sounds whose remote familiarity did nothing but propel the sense of confusion. This incursion into a non-art context-undoubtedly the point of the whole exercise-is a further extension of Marclay’s inclination to use ordinary linguistic elements to build something extraordinary. It was 1993 when Marclay presented White Noise, a room-size installation made of photographs facing the wall. Exactly 20 years later, his investigation into the evocative power of images and sounds might have technologically evolved, but it has lost none of its momentum.

Michele Robecchi is a writer and curator based in London. A former managing editor of Flash Art (2001-2004) and senior editor at Contemporary Magazine (2005-2007), he is currently a visiting lecturer at Christie’s Education and an editor at Phaidon Press, where he has edited monographs about Marina Abramović, Francis Alÿs, Jorge Pardo, Stephen Shore and Ai Weiwei.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.