« Features

Don’t Believe Miss Liberty. A Talk with Edgar Heap of Birds

In the national conversation on racial inequity, one group is continuously left on the sideline-those who were here first. Given that Native Americans precedently inhabited America, one would think their inalienable rights should at least match those of any settlers. But as history demonstrates, they don’t.

In the national conversation on racial inequity, one group is continuously left on the sideline-those who were here first. Given that Native Americans precedently inhabited America, one would think their inalienable rights should at least match those of any settlers. But as history demonstrates, they don’t.

Of the many atrocities against Native Americans, the thousand mile death march known as the Trail of Tears is probably the most recited. But throughout U.S. history Native Americans have suffered numerous injustices, many of which have left our collective memory. Even the Great Emancipator, President Lincoln, isn’t clean. His order to execute Dakota Indians in Minnesota resulted in the largest mass hanging in our country’s history.

Edgar Heap of Birds is a provocative artist bringing attention to the sad irony which is the plight of Indigenous Americans. Cheyenne by blood, his work utilizes contemporary conceptual and postmodern tactics to expose some of the less civil accounts of American history, ones that get little attention in today’s press. From large scale celebratory sculptures like “Wheel” to road-sign-looking text based installations, his work addresses the issues of land ownership, displacement and cultural imperialism still haunting those of Native American descent.

Recently, I spoke with Edgar about his life, his art and his views of contemporary culture. During our conversation, what struck me most was the level of compassion and generosity coming from an artist making such aggressive, politically charged work. As you will see, he embodies the core value by which Cheyenne chiefs are defined, generosity.

By Scott Thorp

Scott Thorp - For well over thirty years now, you’ve created work directed at the issues of identity and the plight of indigenous peoples, mainly Native Americans. Looking back, when was the first time you experienced an inequity concerning your race? How did that make your feel, or how did it change your view of mankind?

Edgar Heap of Birds - My presence in the art world, and my usefulness, does deal with social injustice. But that’s not all I do. It’s an interesting discussion because that’s what everyone knows about. But I also make paintings that are celebratory and sort of diarist drawings and printmaking. And I’ve always done that.

But when I was in college as a second year student at Kansas, I wanted to make a figurative painting of trophy heads-chiefs who were taken, killed or massacred. And one of my instructors encouraged me not to do that. In fact, he discouraged me. Of course, he wasn’t native or a person of color. He said, “Why don’t we just put all the Indians in national parks…. They’ll be better off anyway.” That was his outlook.

S.T. - Your work seems to jump from different ends of the aesthetic spectrum. Some of your most notable works are designed to look like factory-made street signs placed in common areas-something a passerby might assume was made by a local county commission. Then, at the other end of the spectrum, you’ve created monoprints appearing impulsive, almost like someone made them on the way to a protest. “Secrets in Life and Death” is a recent series of work related to that latter category. These are 15″ x 22″ with solid colored backgrounds, and mostly consisting of white, hand-brushed text such as: Delicate Fingers Travel Across Your View, Did Not Know Death Was Coming and Nuance of Sky Blue Over You. One particular one reads, “Indian Still Target Obama Bin Laden Geronimo.” Can you speak to this particular work and what this series signifies?

E.H.B - Yeah, that one is about when they killed Bin Laden. Hillary Clinton and Obama were in the situation room when they all got happy after they received a radio transmission that Geronimo was killed that day-an enemy killed in action. They gave Bin Laden the code name Geronimo, an Apache name.

Obviously, that brings all kinds of horrible issues to bear. They gave the worst terrorist an Apache name of all names. And there are Apaches in the armed services, all over the place. They hunted Geronimo and they put him in prison and put his whole tribe in prison for like ten years. So maybe there is a linkage there-they hated Indians so badly they tracked them, hunted them and killed them. And they hated Bin Laden the same. They’re all put together as strange bedfellows, Bin Laden, Geronimo and the President of the United States.

Edgar Heap of Birds, INDIAN STILL TARGET OBAMA BIN LADEN GERONIMO, 2011, monoprint, 15” x 22.” Courtesy of the artist.

S.T. - To follow up on that, what does it signify when an African American President considers a famous leader of indigenous people synonymous with being an enemy of the state?

E.H.B. - Ya know, the president is clueless about a lot of history. He’s got his own education; he’s got an American education. And he’s mixed race. But it’s more like his education has many blind spots. That’s really the biggest challenge with all the art we are making. We have just such a bad education about history. Even in his first inaugural address, he (the President) called everybody “settlers.” Obama used that in his inauguration so he doesn’t understand the Native American thing at all.

S.T. - Incidents regarding the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner’s police-related death in New York, situations pertaining to social injustice, are coming to the forefront of political discussions. Do you feel the urge to create works inspired by recent events of social injustice? If so, what?

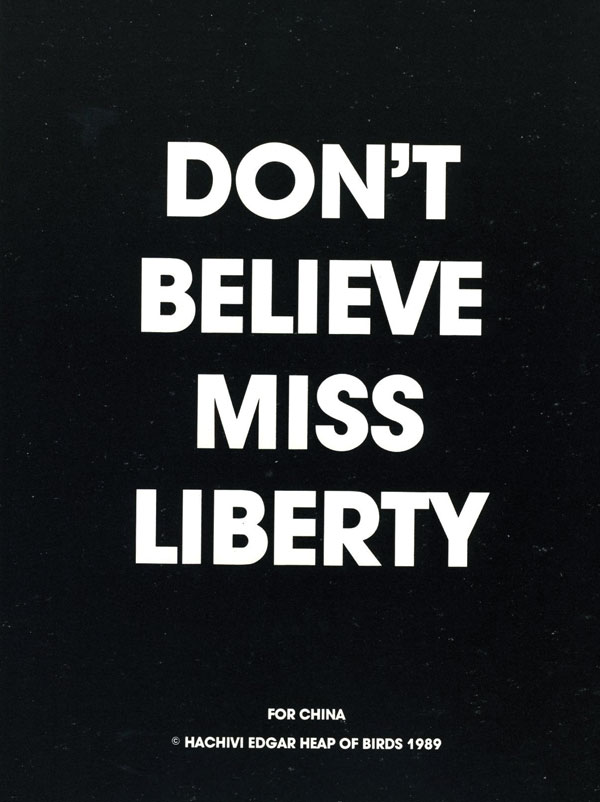

E.H.B. - I was in China a few years ago, Beijing and Shanghai. I made a whole piece for the time surrounding Tiananmen Square. It showed in China, and I was there lecturing. It was just the text saying “DON’T BELIEVE MISS LIBERTY”. For all indigenous people, the Statue of Liberty has her back to them, and she faces the rest of the world.

I have a lot of interest in topical issues. And I’ve been thinking about the black/white issue. We need to reveal that lie and see how we are much more mixed together, from sexual abuses of the U.S. slavery era, than we admit we are.

S.T. - You use short pithy statements with a specific cadence that I’m assuming mimics the cadence of the Cheyenne language. But it’s very contemporary in the way it mimics twitter or texting. What are your thoughts on that?

E.H.B. - It’s in threes. Three words and then they go together to make two sets, six words total. So it’s usually two events described in three words. I’ve been at it for a long time, 30 years or so. But when I think about the cadence, I go back to “Heap of Birds.” There’s three words. I’m not sure, but that could be the reasoning behind the cadence. I also like the Talking Heads, the new wave band, their work like “Fear of Music” and “Life Under Punches.” It might have to do with David Byrne and the way he wrote lyrics and music.

S.T. - Can you tell me a little about the color blue? Wougim is the ceremonial Cheyenne word used to describe the sacred blue sky above.

E.H.B. - That’s my son’s name, Wougim. It’s a ceremonial concept. The sky is made every year. I’m actually involved in the ceremony where the sky is made. I was working in the ceremonial tipi just before my son was born. I was actually privileged enough to hold the sky, Wougim.

In the ceremony, I brought it out of the tipi, showed it to Wougim’s mother. To me, the sky is something that’s ever present. As a traveler, I like the stars a lot. I wanted to give him something that would always be with him. Wherever he goes, the blue sky is there.

S.T. - Who has been the greatest influence in your life as an Indigenous American?

E.H.B. - It would have to be my ceremonial instructors. Those four men have given me a major education, plus they are mentors and colleagues. I’m very close to all of them.

S.T. - Being a Cheyenne and creating art of cultural awareness brings to mind traditional Native American art forms more identified with craft like beading, for example. However, your body of work doesn’t resemble this at all. Much of your work is text-based signage, fairly postmodern in the way it deals with semiotics. How does your education from the Tyler School of Art and the Royal College of Art separate you from the traditional practice of Native American art making?

E.H.B. - England is a different kind of place from America. It’s more cosmopolitan as to what it interjects into society. It’s an awkward thing with all the colonies they’ve created throughout the world. Their society is prolific. They’ve essentially abused the whole world. Being in England gave me insight into society.

The educational boundaries told me to go back home to Oklahoma. After Oklahoma I went to Philadelphia and finished my MFA. By then I was more politicized, which hit a brick wall in Philadelphia. Philadelphia was more of a troubling engagement. That existence reversed at the end of my thesis show when my mentor said, “I understand now.” He learned. I suffered, but he learned. I guess I educated him with all the money I paid into the system. But Vito Acconci and other wonderful artists came and gave me influences and new ideas.

I’m still connected with the East coast. I was just there (New York) the other day. I’m going to show this piece in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in March. I’m showing in New York. And I’m working with colleges in New York and Baltimore and what not.

Edgar Heap of Birds, Building Minnesota, 1990, installation, Walker Art Center, image courtesy of the artist

S.T. - There’s a certain irony in protesting the spread of white culture and being educated within its elite institutions. How do you reconcile this?

E.H.B. - It’s something that you have to learn from. I even taught at Yale. I was senior professor at Yale, which was horrible. But now I know, I know. I think it’s better now with Bob Storr. It was a tough place for me as a professor. You weren’t free to express yourself, even as a professor, or as a student at that institution in the 1990s. But there were useful things.

It’s kind of like the wizard and the curtain. You have to raise the curtain to see what’s behind the curtain. Then all the power goes away. That’s what happened with Yale; it’s a big power. But when I raised the curtain, I laughed.

One of my great mentors was Stanley Whitney. Stanley studied at Yale and taught at Tyler. He is still a leading painter in New York City. I saw some of his wonderful paintings the other day in Soho. He’s a black American painter. I met great people there. Maybe it wasn’t hospitable to me, but I met some great artists along the way.

S.T. - Much of your work points to the transgressions of society. In your mind, which piece does it best? Please elaborate.

E.H.B. - That would be Building Minnesota in Minneapolis. It’s about Lincoln hanging thirty-eight Dakota warriors and Andrew Johnson hanging two more during the civil war era. As I said, how do you reveal the real history of this continent? Lincoln signing that letter is a hidden story. That piece will be shown at the MET with the sign, my picture and a discussion of Lincoln doing that. Most Americans don’t know that happened.

S.T. - I didn’t until I read it last week.

E.H.B. - Yeah, it’s a big thing to hide. We need to break through and get to the real story and truth. That project was painful. People got upset about it. They called me a hatemonger because they felt I attacked this mythical hero.

S.T. - Moving to another piece. Wheel, a fifty-foot installation at The Denver Art Museum inspired by the Medicine Wheel of the Big Horn Mountains, is an incredibly complex work. The more I read on it, the more complex it becomes to me. Can you describe its context and significance to the community?

E.H.B. - They just had the 150 year anniversary memorial of the Sand Creek Massacre. Many of the tribal members came. Two busloads of Cheyenne and Arapaho People from Oklahoma were there, just last week. They go to Wheel to have a candlelight vigil.

The structure of the piece is those trees, the fork trees, which are part of the ceremonial lodge. I meant for it not to be a bona fide tribal instrument. The real lodge has rafters above and 12 forks. Those rafters are not in the sculpture and my piece has only 10 forks. I see what goes on in the Native American life as completing the lodge. In essence, the candlelight vigil completes the piece. Symbolically, it supports the universe. So, I support the people’s activities with the poles as well. Additionally, the history of the whole Middle West is there on every tree from pre-history to Fort Marion in Florida to reservation life and massacres.

It’s also an autobiographical piece about being empowered with advanced degrees from college and coming back to inherit the tribal ceremony and system, and to practice it.

S.T. - Let’s talk about the number 4 for a second. You, personally, have 4 “paints” from the Earth Renewal ceremony on your reservation close to Oklahoma City, meaning you’ve completed 4 cycles of it, 16 years. The ceremony takes place over 4 days, and is a series of 4 songs repeated 4 times. And dancers/participants have to commit for 4 years. And you have a series of paintings titled, Neuf, meaning 4. Can you speak to the significance of the number 4 to you?

E.H.B. - Primarily it’s a balance number. It’s an axis of the northeast, southeast, southwest and northwest. Across that axis goes the solstice. The high end of the continent is the summer solstice, summer sunrise. The low sun rises in the southeast and sets in the southwest. It’s about weather and animals migrating. It’s about the extremes of the sun. And once you understand those four places on the continent, you are set up to understand where you live.

In a weird way, it’s similar to how Anglos think of their world when they say things like, Middle East. And they perceive Europe as the center of the world.

S.T. - So to the Cheyenne, where’s the center?

E.H.B. - South Dakota is where a lot of the articles of the ceremony come from.

S.T. - Back to one of your works. In placing signage with provocative text referring to historical land usage such as “Beyond the Chief” installed at the University of Illinois in Champaign, you are establishing a commentary about ownership, and essentially boundaries. The way government entities like the Corps of Engineers view boundaries is much different from the Cheyenne concept. Can you explain the Cheyenne concept of land usage and boundaries? And how have these differing concepts added to confusion in negotiations between the two?

E.H.B. - I’d like to turn toward what happened in Champaign. They have a mascot. But they didn’t pick one from the tribes in the area like Meskwaki or Peoria. They picked one from Hollywood, a buckskin-wearing one with a war bonnet. Even if they did pick one of those chiefs, those chiefs are chosen within the chief society.

And with the chief society, everything you own becomes the tribe’s. So if someone were to ask you for something they need to use, they can just take it. If you don’t want to be that generous, you don’t want to be a chief. Being a chief is normally associated with being president, CEO or a general of an army. But those plains native chiefs are practitioners of this very loving and generous perspective of being mediators and giving away everything they own. That’s how they rule, through generosity.

And the way they use the mascot to do gymnastics at sports games is all a disgrace. That’s why I made Beyond the Chief. We had local chiefs come in to speak at the university. They were not mascots or icons, they were real people. We were trying to get them to wake up and understand where they were and who was around then and how a chief really behaves.

S.T. - The fact that it was vandalized, and it was repeatedly vandalized, does that mean it succeeded?

E.H.B. - In part, they responded to the work-even though it was through violence. There was some theft too. It became a provocative newsworthy activity for the city in a national way. It’s made to get an inflammatory discussion going, so we can learn about the truth.

S.T. - You have a long standing practice of placing some text backwards in your work. For instance one of the signs in Beyond the Chief reads, “FIGHTING ILLINI/TODAY YOU HOST/IS/MESKWAKI.” The first line, “FIGHTING ILLINI” being in reverse. Please explain the significance of this methodology?

E.H.B. - I started doing that in 1988 when I came to New York. I did a piece for the Public Art Fund. I learned from another tribal member, who was from Rhode Island, that when you enter another tribe’s jurisdiction, you need to acknowledge that. I thought that was important. So when I came to New York, I made a piece that said things like, “Today Your Host Is…” Shinnecock, Mohawk or Cayuga. I wanted to say, to New York, these are your host people, not Edgar Heap of Birds. I was in New York, so it should be about tribal people from the area. I flipped the text backwards for people to look at their past differently. I sent these to the public art fund and they said the Dutch began history here. And I replied “what happened before the Dutch?” You have to turn them around physically. They think they’re looking in the right direction.

S.T. - That’s a fairly postmodern concept of bringing meaning. Do you consider yourself to be a postmodern artist?

E.H.B. - Sure, a conceptual artist, postmodern artist.

S.T. - I feel that your work is about telling stories in unique ways. The stories at times aren’t pretty, but have a powerful moral lesson. Every culture has its stories that continue the traditions. What’s the most profound or your favorite story of the Cheyenne culture?

E.H.B. - There’s one I tell my daughter when I put her to bed about the eagle. It’s about how the Cheyenne selected the animals that would be prized and those who would be prey; they had to make a choice. It deals with a big race around a mountain. Some of the birds glanced off the mountain and left the color on the rock from their feathers. The eagle is one of the fastest and highest flying birds. From this, it became revered. The slower birds became more earthbound and sustenance for the tribe. The eagle remains one of the most prized entities we have in the tribe. My grandmother told this story to me. And I tell my daughter. It’s about being competitive and gaining respect. The other animals aren’t disrespected, though. They fulfill your life as food.

Edgar Heap of Birds with Wheel, 2005, sculptural installation at Denver Art Museum. Courtesy of the artist.

S.T. - How do you wish to be remembered?

E.H.B. - Being accessible and participatory with our tribal people, as a father and teacher, being a ceremonial leader and tribal citizen, all of those layers of engagement are important. The art thing is just one layer. I’m empowered for that one (art) through them. That’s how I get my energy, my guidance. I’ve continued to live that way.

Also, contributing on multiple levels and not being stingy with my energy and knowing it’s not just about art, gallery presence or being a professor. I think it’s great for the native community that you are accessible to your own people. We’ll have an event next week with my mother and sister, a senior citizens’ holiday party. All the senior citizens of the tribe will come and I’ll be sitting there playing bingo with everyone. Blackbear Bosin would have sat there too. That’s how the artists in the tribe work differently from the artists in Chelsea. For us here it’s more about how the birthday parties and the ceremonial camp merge with the art career.

S.T. - It seems like you are absorbing the mentality of the chief. You are very generous.

E.H.B. - Thanks, thanks a lot.

* This conversation took place in February 2015.

Scott Thorp is an artist and chair of the department of art at Georgia Regents University. Specializing in creativity, his book, A Curious Path: Creativity in an Age of Abundance, was published late in 2014. His essay “You’ve Got Talent” is forthcoming in the anthology The ART of Critique/ Re-imagining Professional Art Criticism and the Art School Critique.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.