« Features

Ebony G. Patterson “…while the dew is still on the roses…”

I come to the garden alone

While the dew is still on the roses

And the voice I hear falling on my ear

The Son of God discloses.

And He walks with me, and He talks with me,

And He tells me I am His own;

And the joy we share as we tarry there,

None other has ever known.

He speaks, and the sound of His voice,

Is so sweet the birds hush their singing,

And the melody that He gave to me

Within my heart is ringing.

I’d stay in the garden with Him

Though the night around me be falling,

But He bids me go; through the voice of woe

His voice to me is calling.

Charles Austin Miles. In the Garden.

A line of the 1912 hymn “In the Garden” by Charles Austin Miles welcomes the viewer into Ebony G. Patterson’s mysterious night garden at Pérez Art Museum Miami. “…while the dew is still on the roses…” starts a journey to explore beauty, race, class, the body, visibility, agency, power as well as colonialism and post-colonialism within the context of the garden and the artist’s use of the garden in her practice at large.

What is visible? Who is visible? Who has access? Who gets to see what? And what does one see? The journey most certainly begins with questions.

If a tree falls in the forest, does it make a sound? This particular question has always been the artist’s “pervasive thought.” Says Patterson, “The idea is that somehow for the tree to have acknowledgment it would require somebody else’s presence in order to see it.” She continues with another line of questions. “What does it mean then to bear witness? Who is allowed to witness in that moment? Does it mean that because what you do is not witnessed, that there is no acknowledgment? Does that then mean that you do not exist because you are not acknowledged?”

“Ebony G. Patterson . . . while the dew is still on the roses . . .”, installation view at Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2018–19. Photo: Oriol Tarridas.

The garden invites us to engage with those questions, grapple with them, investigate the larger context and maybe find answers. Everyone walks into the garden alone-dark, glistening, glittering, exuberant, complex, invigorating-one can almost smell the flowers that sprout from walls and in between tapestries, whether in silk, glass or wool. Poisonous flowers cover grave-like mounds and walls, but hidden underneath the artist has also placed healing pants like lavender and eucalyptus. The garden’s ecosystem is a delicate balance.

The combination of survey and site-specific installation spans 13 works from 2010-2018. The Jamaican artist’s most significant presentation of works to date, the exhibition specifically takes a close look at Patterson’s use of the garden in her practice, expanding on meaning and conceptual content as well as imagery and visual presentation, featuring powerful and in-depth references to the cultural, historical and sociopolitical context, the Caribbean diaspora and connection to global black culture.

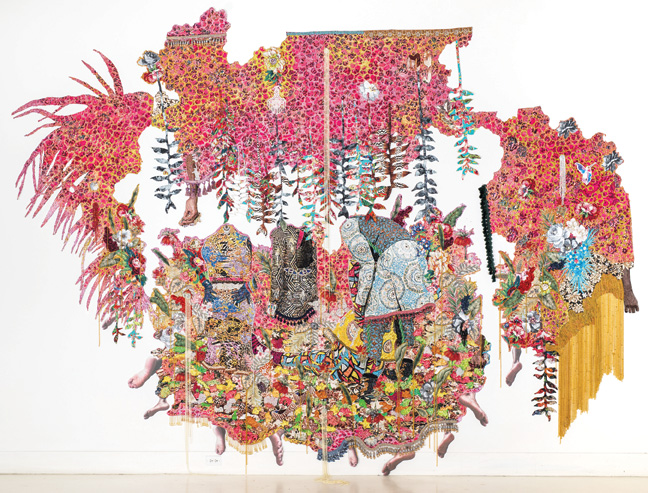

The visually dense environment of the installation is a continuation of each work and tapestry translated into the exhibition space at large. The night garden is a space of beauty and burial, life, growth and death, a space for mourning with fleeting aesthetics, populated by plants, butterflies, hummingbirds and bodies, at first hidden but revealed slowly between the plants and bushes and leaves until the three weeping kings come into full view in their entire larger-than-life glory.

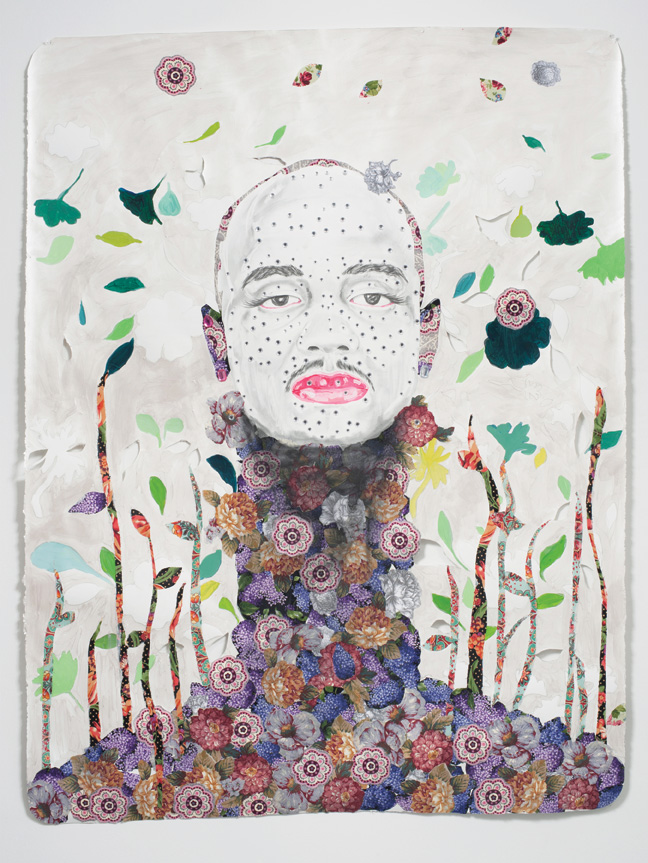

Ebony G. Patterson, Untitled Species VIII (Ruff) . . . , 2012, mixed media on paper, 65 ¾” x 50.” Collection of Marti and Tony Oppenheimer, Beverly Hills, California. Courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

In Patterson’s works, embellishments are heaved thick upon tapestries and other surfaces. She understands how to delicately balance the interactions, creating pieces that visually reflect the contextual depth of her work. The layers of rhinestones, lace, beads, glitter and sequins are carefully arranged, every piece adding a fragment of meaning and content to a larger narrative. She places them with consideration and a painter’s sensibility of color and composition. Like plants in a carefully planted garden, placement decision can either create an environment of nourishment, symbiosis and beauty, or death and decay. This garden also becomes a metaphor for colonial and post-colonial societies, inhabited by the colonizer and colonized in shifting ontologies, environments and political and cultural conditions.

Ebony G. Patterson. . . . wata marassa-beyond the bladez . . . , 2014, mixed media on paper, 85” x 84.” Collection of Doreen Chambers and Philippe Monroguie, Brooklyn, NY. Courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

“I was really interested in the idea of how foliage or shrouding also becomes this opportunity to conceal and to hide and also to reveal,” says Patterson. “As time went on, I started to think about gardens in terms of the idea of utopia, but a utopia that has gone dystopic. I started thinking of the garden as a postcolonial place and the idea that a garden is an amalgamation or collection of ecologies that are living together, but the sustainability depends on what plants are put next to each other and how well they thrive together, what things ay eat each other or not. In many ways, I am kind of thinking about how a postcolonial space kind of mirrors a garden in that way, and in many ways, we are the plants in that space. I am interested in the social spectrum in terms of thinking about colonial and postcolonial lexis that we have inherited in society. What does it mean for particular people to be ranked in a particular way or to be seen as having power and access simply because of the color of their skin or simply because of wealth or social status? And what does it mean for particular people who give us presence in terms of visibility-geographically or socially-not to also have power and status and acknowledgment?”

Interestingly, in the artist’s native Jamaica, inner-city communities that historically have had little economic power or visibility and were often marred by political violence are concrete living environments and tenement yards but they bear names like Tivoli Gardens or Seaview Gardens, thus conjuring images of lush tropical beauty, reminiscent of the fertile lands of possibilities promised to garner interest in development in Caribbean colonies in the past or being sold by the tourism industry today.

Ebony G. Patterson, Dead Tree in a Forest . . . , 2013, mixed media on paper, 87” x 83.” Collection of Monique Meloche and Evan Boris, Chicago. Courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

As one moves through Patterson’s overgrown garden, one stumbles upon disfigured bodies that seem to be buried in the shrouding, just like the 13 artworks that are embedded in the garden space like jewels. The video installation The Observation: The Bush Cockerel Project, A Fictitious Historical Narrative serves as the first introduction to bodies in the space, addressing masculinity constructions and investigating the importance of the acts of witnessing and of being witnessed. As with many of Patterson’s works, the video installation is focused on persons considered to be at the lower end of the social spectrum. They are part of the garden’s ecosystem and albeit often neglected, though they play an integral part in understanding the garden’s existence and beauty.

The tapestries in the exhibition continue to bestow visibility, intentionality and power to the black bodies. Used throughout history to decorate royal homes, Patterson’s contemporary versions of tapestries address disenfranchised populations through imagery, content, wall placement and installation in the museum space. Additionally, the cheap materials from Walmart imitate the expensive and decadent tapestries of royal homes as if a layer of class commentary was conceptually woven into the fabric.

“One day at 2 a.m., I strolled through Walmart looking for some materials, and there was a photo tapestry hanging in the photo area. It was a photo throw. You can get your grandkids or loved ones printed on it. I started thinking about the history of tapestry in relation to painting, and I started thinking contextually about the relationship it had to domesticity and the feminine. Before what we know as painting became popular, it was tapestries that would sit in grand castles and tell grand narratives of the conquests of the colonizer.”

Ebony G. Patterson. . . . they stood in a time of unknowing . . . for those who bear/bare witness, 2018, hand cut jacquard photo tapestry with glitter, appliques, pins, embellishments, fabric, tassels, brooches, acrylic, glass, pearls, beads, hand cast heliconias, and artist-designed fabric wallpaper (not pictured). Courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

Patterson creates new narratives and confers the significance of historical tapestries to her subjects. Her tapestries celebrate such topics as the Caribbean, black culture and the African diaspora. The black bodies in her works are in direct dialogue with the iconography of the garden. She speaks of the violence perpetrated against these bodies, addresses how the black male has been weaponized, then lets her art articulate protest and outrage. Inside the garden, the black body is at the center of a narrative and instigates a dialogue about contemporary black culture.

The contemporary Jamaican cultural space specifically is largely defined by dancehall music, lifestyle and ideologies communicated through lyrics and external cultural markers, including post-colonial definitions of masculinity and gender relations, as well as class and race divides and dichotomies. Dancehall gives visibility to participants who are often the most socially invisible. The “bling bling culture” that Patterson’s use of embellishments references is an example of how colonialism affects class-in the Caribbean context inextricably tied to race-in society today as participants in the dancehall space are perceived to be of lower socioeconomic status. Dancehall has to be understood within its historical context. One gold chain is good? Well, that means that 10 are even better. Status symbols like jewelry and designer clothing have always been a marker of status and wealth, and in inner-city communities, where access to upward social mobility is restricted, the meaning of exterior status symbols intensifies.

In Untitled Species VII (Ruff), Patterson focuses on a man’s bleached face to start a conversation on skin bleaching, as the standards of beauty dedicated to Eurocentrism based on colonial indoctrination almost automatically create an equivalency between light skin and privilege and access. It also investigates Jamaican masculinity, with all its dialogue and discussions on male marginalization, machoism, patriarchy in matrifocal societies and homophobia in dancehall.

Says Patterson, “Skin bleaching is such an aggressive act. There is still this standard of white European beauty. The sense of what is beautiful or aspirational where beauty is concerned is still white. If you exist in a society where you are not on the lighter spectrum and if your class is also low, you have multiple layers of dismissiveness. What does it mean for one to exist in a space that, because of the shade of your skin and your class, you have no visibility? What does it mean, then, to take this material and erase yourself, to claim your visibility through erasure? That’s an incredibly aggressive act. The other thing that is also interesting to me is that these people are also creating light on themselves. The act of lightening relates to this idea of creating spotlight, attracting light to yourself.”

The claiming and reclaiming of space and visibility, the demanding and gesture of actively taking agency, not waiting for others to witness or for others to co-create meaning, recurs throughout Patterson’s practice. Through her work, she bestows honor and dignity and beauty upon the bodies, whether appearing in her tapestries, video installations or drawings. The bodies are adorned and celebrated. Reminiscent of adornments in Jamaican dancehall, Trinidadian carnival or Bajan crop over celebrations, Patterson’s embellishments layer Caribbean culture, African heritage and contemporary black culture onto a foundational global discourse on race.

In the oldest work in the show, Entourage, the garden is evident only subtly via the use of floral designs as a decorative component and the idea of the garden as an ecosystem that can metaphorically explore family and society.

“I was interested in the idea of the family portrait and what constitutes a family portrait. Who gets to sit in the center?” Patterson says. “I was also interested in other kinds of structures that relate to family, especially in working-class spaces and the role of gangs as a communal or familial structure. There seems to be a leader in the middle. As each person comes in, we can figure out who that person is and who are the other figures that may relate to him. Each of them are tipping their head. I always would reference the mug shot as a way of referencing stereotypes of the black male body. There is something that happens with the tipping of one’s head. It is not just about cool. It is definitely not just about bravado. There is dignity. If you even think of historical images that are painted of kings and queens, there is an uprightness that happens from the center. And there is a confrontation that happens in the gaze. The idea that one also tips ones’ head, there is a claiming. This is an interesting way of asserting power. Thinking contextually also about the spaces that those people come from, they are spaces that are not allowed to have that kind of power.”

The work demands an upward gaze from the viewer, another tipping of the head. Patterson typically shows her work slightly above eye level to demand attention for the black men and women directly or indirectly represented in her work. She, again, claims visibility.

What is visible? Who is visible? Who has access? Who gets to see what? And what does one see? The journey through Patterson’s garden ends in a hidden, chapel-like space. The three-part projection, “three kings weep,” ends with three young black men claiming power with the gesture of crowning themselves, not needing others to bestow upon them any validation. Juxtaposed with the voice of a young boy reciting Jamaican poet Claude McKay’s 1919 poem “If We Must Die,” we see the kings weeping as they adorn themselves in elaborate clothing by Jamaican designer Chris Pablo, along with jewelry and accessories. McKay’s poem on racial violence, as relevant in 2019 as it was a hundred years earlier, also brings into stark contrast the intense beauty of the garden with the poison that lays within, making burial and renewal may sound like an enticing proposition.

“‘If We Must Die’ was Claude McKay’s most political and probably his most popular poem. It was a call to action. There is a lot of tension and anger in the poem, but I was really interested in how a poem written in that time still has so much resonance with this current moment. The poem is being read by a young boy. I was interested in juxtaposing two vulnerable, the idea of the young black male always being seen as weaponized regardless of standing or stature, and he is weeping. But as he is weeping, the child that is reading the poem is essentially reading a call to action. If we must die, let us claim this moment for ourselves. We already know how they see us. We will decide the terms; we will not leave this to somebody else.

“The last act is that they each crown themselves. One crowns himself with a bandana, one crowns himself with a hat, and one crowns himself with a pair of reflective glasses. I was really interested in thinking about the act of crowning. Crowning happens to you, you do not do it yourself. The fact that one is claiming dignity for yourself, you are doing it onto you. You are not waiting for somebody else to give it to you. It is another powerful act. The works is also projected incredibly large; it fills the room from floor to ceiling, and you are sitting at the feet of these three young men so they are looking down at you in a kind of confrontational, frustrated gaze as they get dressed. It is a lot more somber. It requires a kind of stillness in a way that does not happen in the rest of the exhibition.”

“Ebony G. Patterson . . . while the dew is still on the roses . . .” installation view at Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2018–19. Photo: Oriol Tarridas.

The stillness in the end continues. While the dew is still on the roses there is still time, more time, to grapple with everything and take a stroll through the garden once more to reflect and become a body in this space with McKay’s call to action echoing in one’s mind:

If we must die, let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursed lot.

If we must die, O let us nobly die

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

O kinsmen! We must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Claude McKay. If We Must Die, 1919.

Heike Dempster is a writer, photographer and communications consultant based in Miami. After graduation from London Metropolitan University, she lived and worked as a music, art and culture publicist, journalist, and radio host and producer in Jamaica and the Bahamas. She is a contributing writer to ARTPULSE, ARTDISTRICTS, Rooms, MiamiArtZine and other local and international art publications, websites and blogs.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.