« Features

Weaving Metaphors. Exploring the Known Within New Contexts

Artist Nari Ward, born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1963, moved to the U.S. at age 12, where he attended the School of Visual Arts in New York and received his Bachelor of Arts from Hunter College and Master of Fine Arts from Brooklyn College.

Artist Nari Ward, born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1963, moved to the U.S. at age 12, where he attended the School of Visual Arts in New York and received his Bachelor of Arts from Hunter College and Master of Fine Arts from Brooklyn College.

Ward’s artistic investigations reference urban space, performance, the dynamics of power and politics, ideas of migration and movement, vernacular traditions and his native Jamaica. His practice is defined by his use of varied media, including large-scale installation, assemblage, sculpture, interactive works, video and photo documentary.

The recurring incorporation of experimental materials and found objects is integral to Ward’s work. His practice of weaving these everyday objects into his art, thereby creating new realities and contemporary narratives, offers an opportunity to the viewer to experience more about themselves by exploring the known within new contexts.

By Heike Dempster

Heike Dempster - Can you share some of your first experiences exploring art and what inspired you to become an artist initially?

Nari Ward - I think one of the things is that I had the facility to draw and depict what I saw in front of me. I got recognition as the class artist in high school. When I came to New Jersey to go to grammar school, I was in a community where we were the only blacks. It was a suburban community and mostly white community. I felt the double challenge of being black and also speaking a different dialect, when I was young especially. Now I can switch on and off. Not then. I felt the sense of being an outsider and feeling alienated and then, when somebody realized that I had the facility to draw the other students, the new label of artist was placed on me, and I kind of latched on to that because that felt more ambiguous but also more interesting, as opposed to being told what you were supposed to feel like. I guess this idea of “artist” was kind of cool, because people did not seem as if they were threatened by that. And I felt more used to this idea of being connected through that role.

H.D. - You were born in Jamaica. How does Jamaica feature into your work now?

N.W. - A lot of it is dealing with the memory of the place. It is a place that I feel a strange rootedness in but at the same time a distance from. It is this combination of feeling like I know the place, but then the knowing of it comes through some other space, memory space, or through smell. Even now, when I walk into a shop, maybe a bakery in Brooklyn or Harlem, and they have patties or spiced bun, it will just trigger some memory from when I was in Jamaica. That leap in time happens for me. It allows me to sort of dream into it, because there is something there, even though it is ambiguous. It is something I grapple to find. It has become a place of inspiration more than reality.

H.D. - There is a very large Jamaican diaspora in New York. How has that experience shaped you and your art?

N.W. - It is very strange. I am lucky enough to participate in that through the music and my early experience of being in Jamaica and that sense of connectedness and language. When I need to turn on the patois, then I can do that, especially when I am around the rhythm, and so I get access to this community, but at the same time they do not necessarily see me as a Jamaican artist because they know that I have been living in the States. It is very interesting, almost a kind of paradigm. But then, when I got to Europe and do a project there, I am the Jamaican artist. It is very strange how the labels get placed. I have gotten to the point where it does not bother me anymore. As a matter of fact, I have even made it a source of inquiry in my work. Certain projects deal with me trying to talk about what is Jamaican-ness, what is the expectation of a Jamaican versus what it is to be a Jamaican person, and that sense of being an immigrant, coming from a place and not having access to it anymore, and how those things play out in who that person might be or how they may be perceived.

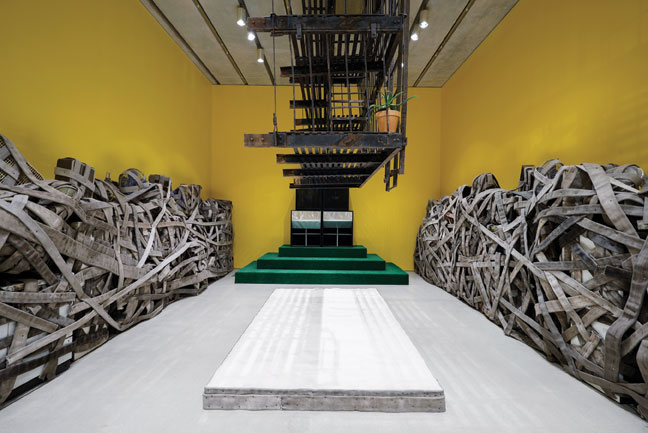

Nari Ward, Happy Smilers: Duty Free Shopping, 1996, awning, plastic soda bottles, fire hose, fire escape, salt, household elements, audio recording, speakers, and aloe vera plant, dimensions variable. Installation view at Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2015 Photo: STUDIO LHOOQ.

H.D. - Do you think some of these labels might be limiting and the absence of those labels might give you a wider audience? What has been your experience?

N.W. - I think they need the labels. I think people need the labels to categorize you. I am always one to-as an artist especially-to not try to conform to the label. Use it if you feel it is necessary and then also be ready to subjugate it if the ideas demand it. “Sun Splashed,” at Pérez Art Museum Miami, was a survey show, and the curator, Diana Nawi, was very clear about what her interests were in the research done on my work over the years, and we were really able to play with those two conversations of the Caribbean and urban sensibility.

H.D. - Let’s talk about “Sun Splashed.” Can you tell us more about the exhibition and the title please?

N.W. - “Sun Splashed” is getting its title from a reggae festival from the late 1970s to the late 1990s. It was a very important festival. It was an international festival where all the reggae artists would play and people from all over the world would come. I remember this in my youth. It was the festival. I guess it does not happen anymore. The reason why that work came up was the idea of the watering of the plant. The splashing of the water. It was also this idea of cultural rootedness and entertainment spectacle. I kind of wanted to bring those two things together, this idea of the spectacle, but then talking about this person, who seems to be maybe a houseplant. Out of place or maybe even kind of vulnerable. There is something about the title that worked for the activation of the water but also the activation of the viewer, in terms of being associated with the spectacle. The overarching component of the exhibition is to bridge this interest in the Caribbean, my Caribbean memories and investigations and curiosity, and then maybe even nostalgia, and then my questions of America and the kind of urban, black American investigation in my neighborhood in Harlem, where I live. I feel like this is great. Miami is almost like this kind of gateway to these realities, and I feel that being in this space.

Nari Ward, Happy Smilers: Duty Free Shopping, 1996, awning, plastic soda bottles, fire hose, fire escape, salt, household elements, audio recording, speakers, and aloe vera plant, dimensions variable. Installation view at Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2015 Photo: STUDIO LHOOQ.

H.D. - Your work often draws on personal history and examines history in general, especially in your works with found objects. Can you talk about your use of found objects?

N.W. - I sometimes do these site-specific projects where I am going into a new environment to make a new work in a different place and really reacting to and improvising around context and culture. I think that forces one to, sort of, not use the normal toolbox that they would use if they were in the studio, the kind of psychological or physical toolbox. That happens when I do the site-specific work, and the found objects are the same thing in the sense that you come up on something that talks to you and then you have to figure out what that conversation can be and how you can build on that conversation. So it is really an opportunity to grow. I am never quite sure. People have brought stuff to me they think is interesting, and they say: “Oh man, look what I found. You work with baby strollers. Look, I found this old beat-up radio.” And I say: “Oh yes, thank you man, that’s really great.” But then I have nothing to do with it because I did not come up on it. It does not tell a story to me. It may tell a story to them, and so I acknowledge that. It’s hard for me to get excited about it if it doesn’t trigger some necessity of meaning. That necessity of meaning kind of happens to the found objects. Finding out how can this thing be what it is, at first, because people see what it is, but how can another meaning be brought into it, how can other ideas be brought into it. I have to figure out how to break it up. Break it up in terms of where it belongs and then find a new place for it. Basically, that’s all I am trying to do all the time with my use of weaving. Weaving is an element that I use in my work all the time. If I was to say just one thing that I am, it’s just a weaver. Not a collage artist. No, I am a weaver. I hope to put different materials together so they become something else.

H.D. - When did you first explore the idea of weaving?

N.W. - I kept doing the stuff where the way things are joined was always about blurring the boundaries. I was not just interested in putting wood and metal together. It would be how to find an innovative way to bring them so they seem like they either are concealing each other or coming out of each other. So this idea of weaving became a really intricate component of that because you are not clear where one thing ends and one thing begins.

H.D. - You also apply the weaving conceptually, as you weave together ideas. Thinking about the materials, literally and conceptually, I found the idea of the ‘scandal bag’ very interesting.

N.W. - Sometimes language triggers engagement with things. I really try to think about the titles a lot. The title for Scandal Bag; History Feeds Mistrust came before the work even. The scandal bag was always something I grew up with and thought about. This is a very strange device. It’s almost like talking about storytelling, but not the normal way of telling a story. What I liked about the idea of the ‘scandal bag’ is that people impose their notion of what that person is or what that person is carrying based off maybe their own bias or maybe their own jealousy or whatever, but they kind of build the story. I felt like that’s kind of what I am doing. All my work is a little bit of a ‘scandal bag’ because I am trying to give them just enough so they think they know what they are looking at but then they have to construct their own narrative around it. So I was very much interested in how to use this idea of the ‘scandal bag’ in a way that brought some other kind of content to it or revealed the idea of a folktale. In this ‘scandal bag’ image-it’s a diptych-there is a character who is me, kind of concealing himself, so the bag becomes a mask, but then the bag is also an object. So it is both. This bag, just like the story, becomes a way to mask something, to talk about something else that isn’t or may not be fully apparent, but at the same time to talk about power and ownership. The idea behind the diptych is very much about how the scandal bags can become sort of fodder for urban lure because the whole premise of it was just how these scandals, these things that are in our neighborhood, become perceived as being real. It’s called “History Feeds Mistrust.” That is the full title of the scandal bags. “History Feeds Mistrust.” I always thought like people believe things. Like they believe that drugs were smuggled in the 1980s into the urban environment by the U.S. government, and the reason they believe it is that there is enough evidence in history to say that this could happen. The same with Katrina. Spike Lee did a documentary on Katrina. What was really interesting, he did interviews of the authority, the city authority, and then he interviewed the people on the street, and the reading of that storm was so different, and it was all based on people’s experiences and mistrust towards authority. I really wanted this piece to indulge in these ideas.

H.D. - How would you explain what a ‘scandal bag’ is to someone who is not familiar with the term or meaning?

N.W. - The idea of calling ever pervasive mundane plastic bags alternate names are a fact in a lot of countries, including Jamaica where they are dubbed ‘scandal bags.’ The notion that something hidden or unseen is made into a story or possible rumor is perhaps a basic aspect of human nature. It is a means to control what you can’t see as well as making sense of something suspicious, especially if the individual holding the bag is perceived as an outsider or unruly. The speculation that is offered says just as much about the narrator as the subject matter, perhaps more. My character uses the bagged persona as a mask as well as a screen. We see his bag emptied; pictured alongside the perverse images of grocery yet he remains elusive. The hyper presence of the fruits and sliced meats does more than render him a passive consumer; he is in control of his own concealment. This act of both secreting himself with his bag and presenting his bag as subject generates a portrait of a conspiracy.

H.D. - You inserted yourself into the storytelling and brought that tradition of storytelling to the diaspora.

N.W. - That, for me, is important. The idea of wanting the work to be almost like a bag for people to put things into, and the scandal evolves, and they are creating their own scandal. Seeing artwork as a scandal is really interesting because that allows for the viewer to be, one, mischievous, but also be inventive.

H.D. - When and why did you first start inserting yourself into the artwork?

N.W. - The ‘scandal bag’ is a good one that you brought up, because when I tried to use somebody else, invariably they became a victim or they became an aggressor, so I could not use somebody else because suddenly it became an other. I used myself so there would be a common, more psychological space that I wanted to declare or investigate. The reason I tried-and the first time I used the bag-were performances that I would make a sculpture that I would activate. Then, later, in Sun Splashed, in those portraits, it was important for me to talk about my sense of not belonging or feeling disconnected or alienated, and not necessarily somebody else, so I became my uncle and portrayed this character in these apartments being watered with their houseplants. It is important that I portrayed the individuals. It is a psychological state that I wanted to bring to the viewer through, as almost like an actor, but leading them through my own kind of exploration.

H.D. - A lot of your work is based on your very personal experiences.

N.W. - Yes. It starts with my inquiry, and then I am hoping that the character that becomes portrayed is something else to the viewer.

H.D. - Does some of your work draw more general conclusions about history’s effect on the contemporary world?

N.W. - One of the big things I like to always think about history it’s that it’s-and that’s why the ‘scandal bags’ are so important-is has always many sides to the story. In some ways I have always been suspect of the history lesson, because it is just a particular view. Then you realized there are many views, and we are just getting a snippet of it. When I am able to sort of fracture it, fracture the history and expectation, it is probably closer to reality than history is, and this idea of reality and history is what I am really interested in, because reality is much messier. It’s about different positions of moments in time, and the history is almost like the work when something is dead because now it does not have all the contradictions and all the different voices that makes it part of what happened. I am always trying to think about how history is a particular object and reality is fractured objects so that it becomes more than itself.

Nari Ward, Iron Heavens, 1995, oven pans, ironed cotton, and burnt wooden bats, 140 x 148” x 48.” Installation view at Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2015. Courtesy Pérez Art Museum Miami. Photo: STUDIO LHOOQ.

H.D. - You also have an interactive piece in the exhibition that examines the immigration process. Can you tell us a bit more about the piece?

N.W. - That is what is called The Naturalization Table. Part of it is, it was really dealing with-all of the work is dealing with anxiety or frustration or some element of maybe anger, and then finding a way to say, okay, this is really something I need to think about, how to give it form. I was applying for my U.S. citizenship and there was this 10-page application process and I never really did it. Every time I would get turned off from it or get frustrated and never got a chance to do it entirely. My wife finally grabbed it out of my hands to deal with it. I ended up starting to do doodles and drawings. I bet I could turn this into a drawing, these 10 documents, so I made these documents, these 10 documents, more like drawings, and I decided I wanted to figure a way that these can have a kind of a dialogue with the viewer that demands more than just them viewing in participating and ownership. Part of the naturalization process is that you come to the table, you bring your ID, you fill out a form, a one-page form, there is a photo that is taken of you and it is stapled on to the ID, you sign the form and a notary republic is going to be there so they all stamp it to authorize that this is you, so you have to make sure it’s you. And in exchange for giving us the form with the signature on it, you get a full package of the drawings as fair trade. What’s really exciting to me is, the ownership of that drawing only happens if we have your image. Somebody might say, Oh, let me grab some of these drawings, but the contract is not fulfilled. It is really about authority and authority playing its role in the creative process. As the packages are given out, the person gets to be on the wall. Almost like a selfie. A formal selfie. An official selfie.

H.D. - You said, the exhibition title and a series of works, “Sun Splashed,” were inspired by a music festival. Do you ever incorporate sound or audio aspects into your work?

N.W. - I have. It is a dangerous, dangerous material. Sound because it’s so powerful. It’s so pervasive. I have brought in sound, but at the same time, because I do not want it to overwhelm, this idea of weaving is very important. I figured out how much of it to bring in. I used one song in one piece because I felt it really needed it. This is not in the exhibition. There is in the exhibition but that was personal. It has a connection to my uncle’s band. He had a band called The Happy Smilers. And that’s the title of the piece. He is a mento singer. It really made sense for the work. He becomes almost the greeter for this installation, and then you walk past his greeting, singing, and then it turns into another world. I have done the sound in another piece called Amazing Grace, where it was a Mahalia Jackson rendition of the gospel standard. It was this huge installation of 365 abandoned baby strollers. It was really important to use the sound to balance the sense of crisis and sort of bring it into the space of redemption that I really wanted the work to have. So, sound is important, but I am very careful not to just throw it in as, “Oh, this is cool.” It has to be necessary.

“Nari Ward: Sun Splashed,” Installation view at Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2015. Courtesy Pérez Art Museum Miami. Photo: STUDIO LHOOQ.

H.D. - Do you listen to music when you work?

N.W. - That is the one thing, if I hadn’t been a visual artist, I would have wanted to be a musician. I wanted to play the saxophone, and-it is a kind of unfortunate story-they were willing to teach us in junior high school but my mother didn’t have the money for the lessons. So I never really picked it up but I would have wanted to play. I just put all that energy into the visual arts.

H.D. - What are some of the most unusual materials you have worked with?

N.W. - The most challenging but the most applicable to the idea of being Jamaican even was codfish. I made a saltfish floor. A codfish floor. I was basically cutting the fish into squares and then using the squares as, like, tiles, where you would even leave room like grout, leave room between them, and then the space in between would be the salt. And the salt-I thought, okay, this thing is not going to last very long and maybe I should not have people walk on it-but after about a week and three weeks, the fish absorbed the salt and it even dries out and becomes hard. It seemed like the salt became like the preservative for the entire floor, so I had a floor that you could walk on fish. It was really special. For at least the first two and a half weeks it smelled like you were in the fish market. And people walked in, “What’s that smell?” It got me into a lot of trouble because initially the first time I did it was in Holland and this one town in Holland, apparently they have a history of having been fishermen and I think it brought up a lot of-the people there, it almost was like they were physically sick smelling it. Something in their history. That’s really interesting. I did not know that. When it started to dry out and there was less smell, they enjoyed it. Initially they looked at me though, like, what is this guy doing? Is he saying something about us? But it is codfish, the national dish of my country. It is a very interesting material because it talks about the conquest of the world. It’s an interesting material that changed the entire globe. For me, it’s always inspiring to work with what’s already present. It’s kind of honoring that.

H.D. - What aspect of your process do you enjoy the most?

N.W. - I think the making is the most anxiety-inducing but also the journey. When I know I have the material that’s talking to me and I have the idea of what I want to do with it and it doesn’t necessarily do what I want it to do, then I have to let it evolve, and that’s scary, because then I am not sure where it’s going to take us. It’s exhilarating, but it’s also very stressful. There are works that you make and you say, hmm, I should not have done that. Listen to this part. Then you take it back to the studio and do another iteration. But for me that’s just as valuable. This is never about where you end up but continue a process of moving. That’s really important.

Heike Dempster is a writer, photographer and communications consultant based in Miami. After graduation from London Metropolitan University, she lived and worked as a music, art and culture publicist, journalist and radio host and producer in Jamaica and the Bahamas. She is a contributing writer to ARTPULSE, ARTDISTRICTS, Rooms Magazine, MiamiArtZine and other local and international art publications, websites and blogs.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.