« Features

In conversation with Carl Ostendarp

Carl Ostendarp entered undergraduate study at Boston University in the twilight of the Phillip Guston era. He went on to Yale as part of a cohort group whose work gave a shot of adrenaline to 1990’s painting. He is an associate professor and graduate director at Cornell University who has had over 33 solo exhibitions, 170 group exhibitions. Ostendarp is represented by Elizabeth Dee Gallery in New York City. I spoke with him on July 10th in the David Smith cabin on the campus of the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture where he is a member of the 2016 resident faculty.

By Craig Drennen

Craig Drennen - Not many painters grow up the child of a professional football player. Did that shape your childhood in any way?

Carl Ostendarp - My dad had played for the Giants after World War II, back when their backfield had a roofing business. So it’s not like now.

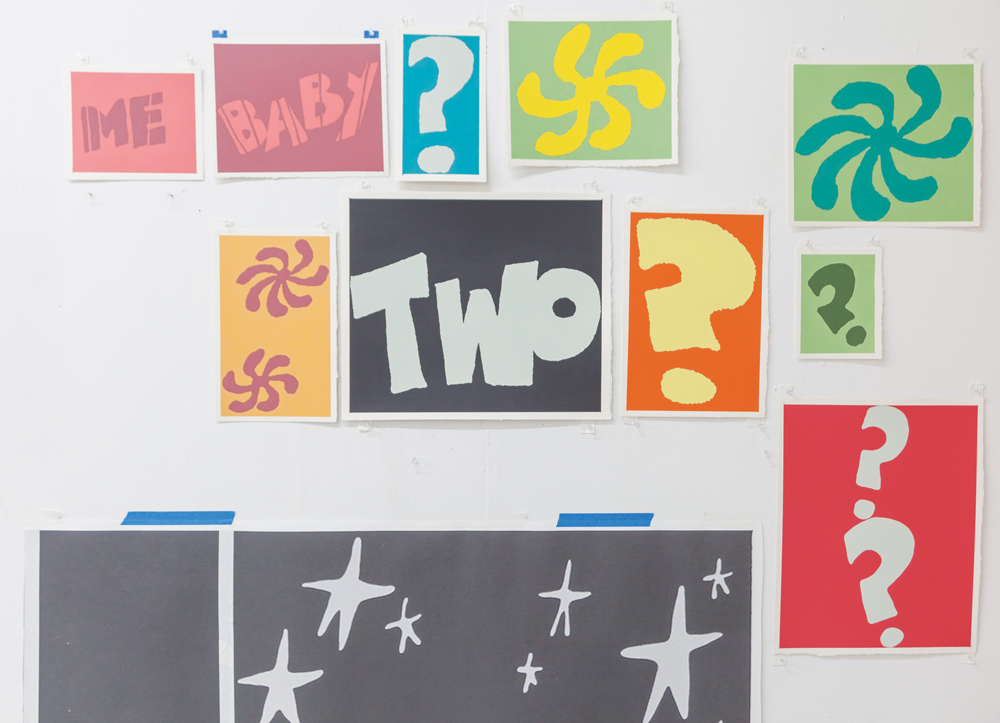

Carl Ostendarp studio (North wall detail), Skowhegan, Maine, summer 2016. Photo: Diego Lama. Courtesy of the artist.

C.D. - Is that true?

C.O. - Yeah it’s true. That’s what he did in the summers in New York. But he was a coach at Amherst College for thirty years, and Williams before that and at Cornell for a year. We lived in college housing on the street between the gym and the football field. It was total football, plus the Patriots used to practice at UMass in the summers so we’d go over and see them because dad knew those people. But he was unusual in that he used to have team meetings in the Amherst College art museum (Mead Art Museum) and he used to go in there before games to, you know, get calm before the Saturday games.

C.D. - Did the repetition and work ethic built into athletic life have any impact on you?

C.O. - (laughs) I don’t know…maybe. The year I played football in high school we lost every single game. Guys would be shocked and horrified and throw their helmets around the locker room and say “Argh! Almost!”

C.D. - I do that every time they announce the artist list for the Whitney Biennial.

C.O. - Me too. (laughs)

C.D. - What was Boston University like when you were an undergrad there? Was the ghost of Phillip Guston still around?

C.O. - Phillip Guston was there my freshman year. The school itself was a bizarre blend of 19th century Beaux Arts instruction-figure drawing, anatomy, and so on-and then German Expressionism, like Beckmann and Kokoschka, by way of the Museum School. It was odd that Guston was there. Jim Weeks was also there and he was really good-from California. This guy John Wilson taught drawing and he was terrific, but my general sense of the school was that they worked really hard to keep you from being creative. They put a lot of work into that.

C.D. - I think that’s not uncommon.

C.O. - Guston would give these slide talks and you had the sense that he had time to kill, coming down from Woodstock. The slide talk would be two projectors and he’d show his own work on one and talk about it formally-this was the year before he died I guess-and would talk about the structure of his paintings. Then the other projector would be projecting Piero and Sassetta and early Italian stuff that he would never mention. He would just have it there, so you would understand that he was comparable to that. He wandered into one of the studios where I was doing a freshman drapery study assignment one night when I had decided that I would paint it like Cézanne. Guston walked in, introduced himself and said that he thought my painting looked good except that it looked like I’d glued colored pieces of corn flakes to the canvas. That was my only personal contact with Guston, and at the time I wasn’t sure if what he said was a good thing or a bad thing.

C.D. - I’m going to wager that it wasn’t good. Was there a period of time before you went to Yale?

C.O. - No, I went straight through. I had done the Norfolk program my junior year and met a lot of people from art schools around the country. This was really the first time I’d worked with people who were really engaged with art. I think Norfolk is the Triple-A team for Yale’s grad school in a way.

C.D. - Who were your faculty and peer group at Yale?

C.O. - Mel Bochner and Jake Berthot were the two faculty I really learned from. My first year and the year after were really amazing. Jessica Stockholder was in painting then moved to sculpture. Ann Hamilton was there in sculpture. Richard Phillips was there, who I had gone to undergrad with. Sean Landers was there, and Jack Risley. Who am I forgetting? Oh yeah, John Currin and Lisa Yuskavage. And lots of others.

Carl Ostendarp’s “Blanks” exhibition, Elizabeth Dee Gallery, 2014. Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee Gallery.

C.D. - Were they making work that in any way resembles their current work?

C.O. - Some were, but not really.

C.D. - After grad school you went to New York City, and were part of the generation that experienced the demise of Soho. Were artists on the ground aware that an era was coming to an end?

C.O. - I got to the city in 1985 so it was a while before Soho started falling apart. One thing that happened in 1988 or 1989 was the stock market crash, which to me felt like a bigger deal than the end of Soho as a gallery center. Before then you had the very real sense that there were galleries you could imagine showing at-maybe White Columns-then there was the next tier of galleries. Things were very hierarchical in terms of who would show where….

C.D. - But the alternative spaces had a prominent role-Artists Space, Art in General, White Columns?

C.O. - Yes, I think that was part of it. For me, and a lot of the people I hung out with, it was White Columns. Bill Arning was running it and it was a real center. A lot of friends had White Room shows there. A lot of small spaces also opened up that didn’t have to announce whether they were an alternative space, or a project space, or a hardcore gallery, because nobody was buying anything anyway. I think that was the last vestige of gallery artists being a reflection of a dealer’s taste, and the beginning of the independent curator era-like outsourcing the selection process. It seemed like a really big shift in a lot of ways.

C.D. - Did there feel like there was a scene available to you as a young artist?

C.O. - We were our own scene pretty much. There was a core group. We worked jobs for money and hung out and drank too much. My studio was on Delancey for a long stretch of time. One up side was that you could get really intelligent response to your work, but there was also this other element of just keeping each other company. It took a while before we realized people were aware of us.

C.D. - Do you think alternative spaces still have a role to play?

C.O. - It depends on the place. I’m also shocked by how bureaucratic a lot of professional activity is now. I’m sure I’m wrong, but I can remember, for example, when there seemed to be very few residencies-Yaddo & MacDowell. But now there are hundreds of them that require images and statements and people doing them on a really regular basis. I think the reason is that it is now very, very difficult to do what I did-move to New York, find a cheap place to stay, and a job that allows you to do your work. I think that’s very difficult now. People now go to residencies to have the community that they used to be able to have right in the middle of their lives.

Carl Ostendarp’s “Blanks” exhibition, Elizabeth Dee Gallery, 2014. Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee Gallery.

C.D. - I think the first time I saw your work in person was back in 2007 at Elizabeth Dee. I was really interested in how you made hard-edge abstraction and the monochrome functioned for you. Thanks to early 1990’s art like Neo-Geo I was used to having abstraction instrumentalized in a social way. Your paintings were different and I liked the mechanics of how you made it work-the way I sometimes feel in front of a Mary Heilman painting, where I can see exactly what the artist is doing but still can’t explain why it’s effective. It seemed to me that your work had a different value system.

C.O. - That was a survey show of twenty years worth of work. I’ve spent a lot of time looking at historical artists from the mid-1960’s to mid-70’s who occupied a space between Pop and hard-edge geometric painting, like Ed Avedisian, Ralph Humphrey, Nick Krushenick, and Paul Feely, the guy who did the jacks paintings at Bennington.

C.D. - I saw a great Paul Feeley exhibition at the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio last fall. When you say you were looking at this small group of artists who were between Pop and Minimalism, what was it that you were looking for?

C.O. - I guess I was interested in what happened in that period of time-early Pop and Minimalism up until 1976 or 1977. You see this explosion of new mediums-installation, performance, video, Earth art. You see this profound change in the definition of the term “artist.” It seems like a lot of these media developments were about increasing the sense of immanence of the work. And a part of that is having greater control over the context, like making the context part of the work. This seems diametrically opposed to the circumstance now, where shows are curated around curatorial themes and there are art fairs everywhere that have no context whatsoever, operating like walk-in catalogs. There’s a funny back and forth during that period between painting that seems involved in the notion of a physical, corporeal thing.

C.D. - Who would be an example of that?

C.O. - Maybe “fat field” paintings and paintings that turn the corner into sculpture. On the other hand there is painting as a kind of drug offering a hallucinogenic experience, like Op art. There was that show that David Reed helped put together, “High Times, Hard Times,” that gave examples of those locations where abstract painting went.

C.D. - That show reintroduced me to Al Loving in a profound way.

C.O. - There are a billion people making paintings and art world memory is like five years, so many amazing artists are forgotten. I was doing this curatorial project with the museum collection at Cornell and found this Dan Christiansen painting that they’d been given in 1969 or 1970. It was huge and they’d never stretched it and never shown it. It’s a spray paint painting, but not one of the coiled bright ones. It’s really Miro-esque. It’s not really a color field painting and it’s not really an example of post-minimal material practice. It’s its own crazy thing.

C.D. - That takes me right back to my early comment about your value system. Your taste in painting is positioned slightly outside the canon. For you Dan Christiansen and the illustrators at Mad Magazine and Dr. Seuss are all relevant.

C.O. - I think we’re the result of all the visual experiences we have so I don’t think acknowledging one’s visual culture is necessarily earth shaking, but maybe what it does do is obviate this “high” and “low” thing. For a while I had this VHS collection of cartoons from the teens and ‘20’s. There’s one Felix the Cat cartoon by Otto Mesmer with a bicycle race on Saturn and the cat wants to get up there so it finds a ladder and uses its tail as a hook or something, then the tail turns into a question mark. In any case, there is a still from it that is almost an exact replica of the Miro painting of the dog barking at the moon, except that the Miro is from 1926 and the Mesmer is from 1914 or 1915. And these short films traveled around the world, right?

C.D. - I think you may have just discovered something.

C.O. - When we look at past things from where we are, it changes what those things mean. This just seems like a much more dynamic situation than the way influence is usually described.

Carl Ostendarp, Charles Kynard, 2014, acrylic on canvas 49 7/8” x 57 7/8.” Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee Gallery.

C.D. - That’s what permits your work to have a different value system-it has different intake sources from culture.

C.O. - (laughs) Well there is secret stuff in the paintings! In addition to the images, there’s a crackpot math thing that I do. And there’s an idea about the “field” that’s as much American color field painting as it is animated cartoon space. I have this idea, that’s also connected to the math, of the ‘life-sizeness’ of the painting. Abstract paintings especially have tended to function historically as either a cartouche, like when Pollock turns the corner when he gets close to the edge. Or as an interpretive representational thing where the imagery is implied to continue, like a Clifford Still. But in Jean Arp’s reliefs and in Barnett Newman-and obviously in the readymade-you have this sense that the image edge and the object edge are contiguous. They happen at the same time and place, and make you aware of how big you are and increase your sense of present-ness in front of the work.

C.D. - Ok, is it possible for you to describe the math you use for the compositions? I saw some notebooks in your studio filled with math notations and I admit that I was mystified.

C.O. - For the “Blanks” show I did with Elizabeth Dee I made a booklet of mathematical drawings, to just ‘fess up in some way. The math comes from this thing that happened right out of grad school when my older brother said he would give me a ticket to Holland if I showed him around museums. At the Stedelijk Museum they have a Barnett Newman painting called The Gate. I had an amazing experience in front of that painting and spent a lot of time trying to figure out what had happened. I eventually figured out that he was exploiting difference between ways we experience things and perceive things with our body. We line up with things because we are symmetrical-two eyes, two ears-so you try to meet the center of something with your own center. If you try to talk to somebody, you line yourself up with them symmetrically…

C.D. - I’m with you so far.

C.O. - …Then there’s another more conceptual mode of perception that you do with your eyes, like a reading perception that scans left to right. I sensed that the Newman painting found ways to trigger your body, which wants to line up with the physical center of the painting, then throw you off with the location of the color divisions because your eyes are telling you that you’re not at the center. I’ve watched people do this crazy dance in front of that painting because their bodies and their eyes give them two contradictory senses of center. This extends the duration of the viewing experience and can make it feel more intimate.

C.D. - That seems like a remarkable discovery.

C.O. - I thought there must also be some relation between the nature of the potential affect of the vertical dimension of a canvas and the horizontal dimension. There’s a set of calculations I developed to place imagery on the surface. To be completely honest, it’s all because I hate the idea of being a stage director making composition the driving force behind image making.

C.D. - Can you explain that?

C.O. - There is this inherited idea that composition is how an image becomes articulate. To me that seemed tied to the assumption that painting is episodic or an interpretation of reality, like a moment in a story. The math guides where the image should be on the surface. More recently, it helps determine how big the paintings should be in relation to the architecture where they are shown. In my last show at Elizabeth Dee it was all three: how many paintings, how images were placed, and how the group fit in the space. It was excessive. (laughs)

C.D. - When I saw the recurring “CO” in your paintings in that exhibition it took me a while to realize it was your initials, and not an abbreviation of some kind. It was a powerfully funny payoff moment for me. It was part of a tradition, like Oskar Kokoschka’s “OK” initials or Stuart Davis’s stencil signature or Ashley Bickerton’s silkscreened name. But it also let the air out of the idea of the artist as a brand.

C.O. - There was some sense in my mind that signing the monochrome was like wrecking it, demonstrating the gap between transcendence and market object. It had been a while since I’d done a show in New York-maybe four or five years. I had the idea that I needed to make that show my last show, as if it was my last show ever. Just in case.

Carl Ostendarp studio (North wall), Skowehgan, Maine, summer 2016. Photo: Diego Lama. Courtesy of the artist.

C.D. - Why?

C.O. - That was just my notion. What would I make if it were the last chance I had. I wanted to up the ante in a certain way. The “CO” meant “company” and “care of” in my mind and it meant care of the monochrome, care of this long tradition. Mostly I wanted to put together a show that wouldn’t make any sense unless you were there. In my mind that was a fight against the art fair, a fight against the lack of contextual control.

C.D. - There was one piece in the back room that just said “Carl” right?

C.O. - Yes, that was me signing the show. The thing that people forget when they mention that show is that the paintings all have titles, and the titles are not my name. The titles are the names of Hammond jazz organ players from the 1960’s: Jimmy McGriff, Jimmy Smith, Charles Kynard. There’s a quality to that organ music that is both pop and related to the history of jazz, and the nature of the Hammond organ, which goes between melody and noise.

C.D. - How do you follow a show like that?

C.O. - I’ve been making these star constellation paintings and these question mark paintings. That’s what I’m working on at Skowhegan, the question mark paintings. I have this idea that one of these question mark paintings will hang on the wall in someone’s home while they’re looking for their keys. That’s the whole idea.

C.D. - What do you have coming up?

C.O. - I have a solo exhibition opening at Elizabeth Dee Gallery in New York on January 14, 2017 at the new Harlem location.

Craig Drennen is an artist based in Atlanta, where he is a professor at Georgia State University. His work has been reviewed in Artforum, Art in America and The New York Times. He served as dean of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and is on the board of Art Papers. He has worked at the Guggenheim Museum, The Jewish Museum and the International Center of Photography.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.