« Features

The Art School Critique

“Critique, etc.”

“…I had a teacher one whole summer who never told me/

anything and it was wonderful.”

Frank O’Hara

Hotel Particulier

From Lunch Poems, 1964.

Let’s be clear. The art school critique is not just talk. It is a conversation that’s supposed to cause improvement. Mentors and peers talk about a student artist’s work to make that artist’s work better, and it’s one of the few mechanisms available to help put the survival odds in students’ favor. The art school critique is goal-oriented, since improvement is part of the educational product being sold, and consumers do like to get their money’s worth. Art production begins in the privacy of the artist’s mind, becomes real in the studio, and then gets hauled out into public for scrutiny. That, in its most encapsulated form, is the function of the art school critique-a goal-oriented conversation that leads to improvement for the sake of survival. For the record, no one is completely certain that the critique-or any part of art education as we currently know it-is even useful for artists at all. I’m reminded of an apocryphal quote by the photographer Garry Winogrand who, when asked to comment on the degree to which education was useful to photographers, is said to have replied, “Can’t help ‘em. Won’t hurt ‘em.”

Art school is a heartbreakingly brief oasis for artists, relatively free from the marketplace, and should allow for a specific type of candor. When students leave academia the critique model they’ve known swiftly morphs into the studio visit model, which is very different indeed. That’s when gallerists, curators and collectors confront fortunate artists to assess whether or not to enter into professional relationships with them. If they don’t like what they see in the artist’s studio, they’ll just find another artist they do like. There’s no shortage of artists, and there’s certainly no imperative to care whether the artist will, or will not, improve their work over time. Why would there be? Students pay tuition for the art school critique experience, but in real world studio visits, neither party is paid to be there. However, there is at least the promise of eventual payoff, which explains why some gallerists haunt graduate open studio events the way ConocoPhillips sniffs for hidden reserves of shale. Resources must be out there, they imagine, waiting to be found. I’ve been on all sides of the art school critique as an artist, a professor, and as a staff member at an artist residency program. The critique language varies somewhat from location to location, in my experience, but the basic mechanics remain the same.

I’ll bracket aside the professionalized studio visit to focus on the art school critique alone. I believe that the “improvement” expectation in the art school critique carries within it an inherited set of implications, such as that artworks begin their life in a state of imperfection, an “original sin” condition that public discussion can help improve. The artist may present their work to a large group, a small group or just one person, but it is still a congregation of wills directed toward a single purpose. If the artwork is lousy-as sometimes it is-then the conversation alters its contours in ways that might take on a revivalist tone. If the work is promising, then the conversation becomes softer, with more nuanced shunting toward positive outcomes-the “blowing on the embers,” as the painter David Humphrey once told me in an interview.1 However, if the work is going well-or in rare cases, extremely well-then I submit that no additional conversation is going to be that helpful. If the artist is managing their practice well and the work is strong, then they begin to resemble a high performing athlete in mid-performance at which point nothing anyone says will make things better. In fact, the disruption provided by talking will likely make things worse.

THE MYTH OF THE “PERFECT ARTWORK”

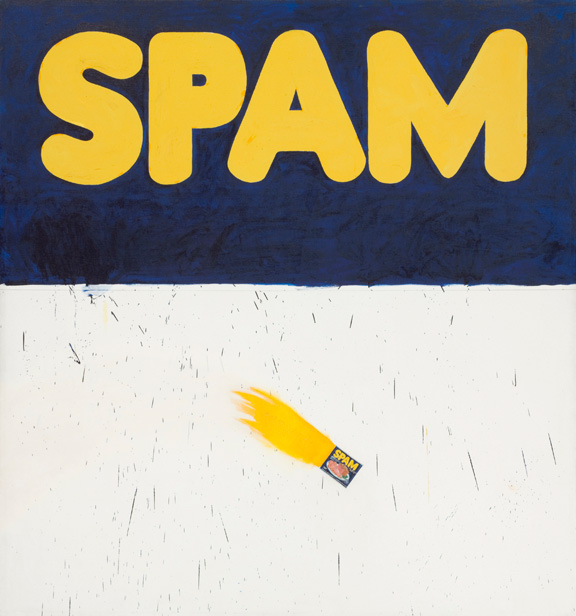

There are people both inside and outside academia who rise up at this point to say, “But there is always something than can be improved.” To this I respond, generally yes. But examples from my own life of art viewing come mind. In 1962, when 25-year old Ed Ruscha made a painting called Actual Size, what useful tip could have been whispered into the artist’s ear during the process of making the piece? I confess that I adore this painting and have traveled great distances to see it. Could there really have been any conversational prompt by anyone else that would have made that painting better? I am doubtful.

The can of SpamTM in the painting rockets through the lower hemisphere beneath a blue swath containing a constellation of letters spelling its own name: SPAM. It demonstrates the premise “As above, so below” as thoroughly as any hermetic text. And it is irrational, inscrutable and possibly glorious. To pile on another example, in 1992, when 28-year old Janine Antoni was chewing on two blocks of high-calorie modernism in the form of chocolate and lard in her Gnaw piece, could anyone correctly tell her that she was doing it wrong? The implications of this sentiment suggest that spoken advice might be most useful in disciplines with more firmly inscribed histories like subtractive marble carving and less useful to new and unconventional practices like biting. Antoni’s blocks of chocolate and lard could have been just the latest iteration of the austere, minimalist cube. Those cubes have come in metal, wood, Lucite and mirrored versions, but when transcribed into chocolate and lard they cease echoing modernism’s high classic period and instead become grounded and bodily. Then, imagine both blocks being attacked by the mouth of a thin, thoughtful young woman who decided that her criticality would be best expressed with her teeth. What critique strategy would be at all useful in that moment of artistic action? Bite more? Bite less? Other examples come to mind, from Picabia through Eleanor Antin and Guy de Cointet, but the point is hopefully made. What, if anything, can one even say to an artist that could be helpful?

What plays out more often is the fetishized notion of the perfect artistic solution and that there exists one set of actions that will lead to the perfect artwork. I have difficulty supporting that ideology, and I go back to sentence number 12 from Sol Lewitt’s 1969 “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” which reads, “For each work of art that becomes physical, there are many variations that do not.”2 As every artist knows, you cannot make everything. Lewitt’s solution was to show modular permutations of his generative idea, with no solution being privileged over any other. Most artists who are not Sol Lewitt chose not to rely on permutations but instead make singular works. What this means is, as the line says, there are many alternate works that never make it to the light of day.

That seems reasonable enough, but it runs counter to at least one hagiographic line of art historical practice that insists that the artist’s genius transmits the force of that genius into every artistic decision, rendering it the correct decision. Therefore, Picasso’s foregrounded still life in Les Demoisselles D’Avignon could only be thus, and Pollock’s handprints in the upper right of Number 1 are the ideal self-referential gesture and could not have been otherwise. In fact, it could always be otherwise. So, when I hear critique conversations driven infinitely long by the grim moralism that there are always things that can be improved, what I hear instead are unselfconscious imaginings of all the variations of the work in question that did not get made. They are not better; they are just the unmade permutations. And that’s not a critical discussion but, at best, one that harmlessly kills time until the critique is over, or at worst, programs artists to believe that artistic success is never arrived at but endlessly deferred. I don’t find that type of discussion any more useful than I would find it beneficial to recite to Carolee Schneemann all the words that rhymed with Interior Scroll. All it would do is list variations of a title that she did not choose, instead of addressing the title that she did choose. But in proper defense of the academic model, mentors sometimes feel like they need to say something, if only because everyone in the room knows it’s a part of the job they’ve professed to do. My advice is to return to the basic goals of the critique process and remember that no one is actually being paid to talk. They’re being paid to enable improvement, and if the best thing a mentor can do to encourage improvement is to not talk, then not talking is what should happen.

Janine Antoni, Gnaw, 1992, 600 lbs chocolate cube and 600 lbs lard cube gnawed by the artist, 45 heart-shaped packages of chocolate made from chewed chocolate removed from chocolate cube and 150 lipsticks made with pigment, beeswax, and chewed lard removed from lard cube. Each cube: 24” x 24” x 24,” installation dimensions variable. Installation view The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

I will soften my earlier point. In nearly all cases there are probably things that can be improved in an artist’s work and some useful words that could be spoken. However, I am wary of simply conjuring up variations and permutations of the displayed work as if that has use value. I maintain that there are also instances when nothing can be improved by talking. And that’s when the smart money keeps its mouth shut.

THE CRISIS OF THE MEDICAL MODEL

If we can agree that in most critique situations there do remain a few things that can be said, then the question becomes just how to say them. In addition to the “original sin” analogy, it’s difficult to completely avoid inherited practices from the medical field. When an artist presents work to a group for an art school critique, the mentors and peers quickly get to work on a diagnosis. The diagnosis may be based on observation and perhaps a few simple questions. Some institutions will follow that up with prescriptive recommendations, such as, “Mix your paint better, read some Žižek and come back next semester.” Other institutions will intentionally abstain from prescriptive suggestions in the belief that concrete instructions on how to “cure” artwork will asphyxiate all other creative channels. In worst-case scenarios, prescriptive recommendations establish a value system where young artists receive praise primarily for following orders given to them by their professors, which may create personality cults around individual professors. I can think of nothing more harmful to the growth of an artist than identifying their professors as a target audience. My anecdotal experiences suggest that most art programs believe that artists benefit most from simply hearing the diagnoses, without the full prescription.

I’ve visited a lot of university art departments, and one of the expected campus duties is to engage in individual critiques inside the students’ studios. This is a well-known, accepted practice from coast to coast. It’s the one-on-one critiques inside the private studio that take the medical example even further. The artist is now in a small studio room with a mentor, a room where they may have been waiting patiently for some time. Perhaps artist and mentor will even be sitting across from each other as would a patient and doctor in an exam room. The mentor scrutinizes the artwork quickly and follows up with pointed questions for the artist. These questions might be about prior artistic or intellectual habits. A snapshot of this moment might resemble Freud’s “talking cure” starring the wise analyst and searching analysand. Artists themselves reinforce this model when they share critique stories with comments that underscore effectiveness, such as “Artist X really listened to me and was extremely helpful,” or “Artist Y specializes in something that’s useless to me.”

MACHINE(D)

But perhaps the medical analogy is too convenient and slightly off target. Maybe it’s not the psychoanalytical model being summoned by the art school critique at all, but something earlier. It might be true that 21st-century medicine has its roots in the early modernist era, during which discussion of the human body was reframed as discussion of an organic machine. (The body envisioned as a series of hinges, pumps and pipelines is a body in which problems can be isolated and repaired.) A machine can be fixed when broken, and parts replaced. Any machine that functions well can always be replaced by a machine that functions better-which is another point to which the “there’s-always-something-that-can-be-improved” crowd still adheres.

But I don’t always agree. There are artworks that come down the line that are alive and smoldering and contentious, and attempts to makes those works more “effective” may only make them more like the appliances we live with every day. In short, we are used to a normative relationship with machines designed with our comfort in mind, so those learned habits may dominate our evaluations when we determine that an artwork should be “fixed” in some way. If we treat an artwork like a machine, then the first adjustments that occur to us will be ones to make it more pleasing and easier to use. This will tend to soften any rough collisions within a work while gently implying function and use value, neither of which conjoin smoothly with artworks. One of the most resilient characteristics of art is that its uses and functions can still be legitimately contested. Or, as Yves-Alain Bois states, “Within our culture the work of art is a fetish that must abolish all pretense to use value.” 3

This leads me to again revise an earlier statement. The artwork does not enter the world in a state of original sin. It enters the world as an imperfect machine that lacks any agreed upon use. How can any critique conversation accommodate such a strange blend of characteristics? I witness attempts in two broad ways. The first method is to focus only on the mechanics of the artwork using the value system granted to machines, while ignoring absence of use value. This approach is remarkably easy, which might help explain its popularity. Mentors discuss the artwork in terms of efficiency, speed, consistency and reliability. Artists are advised to use materials properly, to avoid wasted effort and to rid their studio practice of any misspent hours. Then artists are praised if their output can continue to hit the same note at the same level they’ve demonstrated in their best moments. The goal is not to produce erratic artists who are superlative in one moment then disappointing in the next. Neither is the goal to be endlessly experimental. The goal is to train artists to consistently and reliably produce artwork at a high (that is to say, “high enough”) standard so that the distance between the best work and the worst work diminishes into the steady, dependable pulse of a signature style.

But-and this is an important point-in order to adopt this machine-based model for the art school critique, all parties involved must pretend that they’ve forgotten one important fact: Art has no clear function or use. If you address use value head on, then you admit to the notion that it’s fine to discuss works of art based on a machine aesthetic, when in fact they are mechanisms without a purpose. The conversation about efficiency and consistency is haunted by the likely purposelessness of the result. The history of the avant-garde could be rewritten as a history of research and development for new products that act as an eccentric breed of functionless high-end objects to test the limits of what can be bought and sold. And that would be fundamentally correct.

The second machine tactic often used in the critique environment is to dial down the emphasis on mechanics while amplifying the possibility of legitimate use. In other words, the problem of critique can be solved if art is prescribed an artificial use value, after which all comments align around the degree to which the art does or does not achieve that function. Art has had eras of usefulness in the distant past, as with religious illustration or social propaganda. It has had usefulness more recently, with examples such as Hans Haacke’s institutional critique in the Manet Project at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne, Germany, in 1974, which shown a spotlight into the shadowy back rooms of museum culture and was therefore useful.

So yes, if you declare art to have a clear function, then all parties can talk about how well the work performs that function. But the functionality has to be assigned to art, and in most cases that assignment proves limiting and awkward. If professors told students that all the work they produced must cause measurable social improvement, then a significant percentage of students would be doomed to fail because social improvement often takes longer than a 15-week semester. If professors told students that the function of their artwork was to deliver clear messages to a target audience, then the professors would be requiring art students to think and act like client-obsessed advertisers. Neither option fills me with optimism.

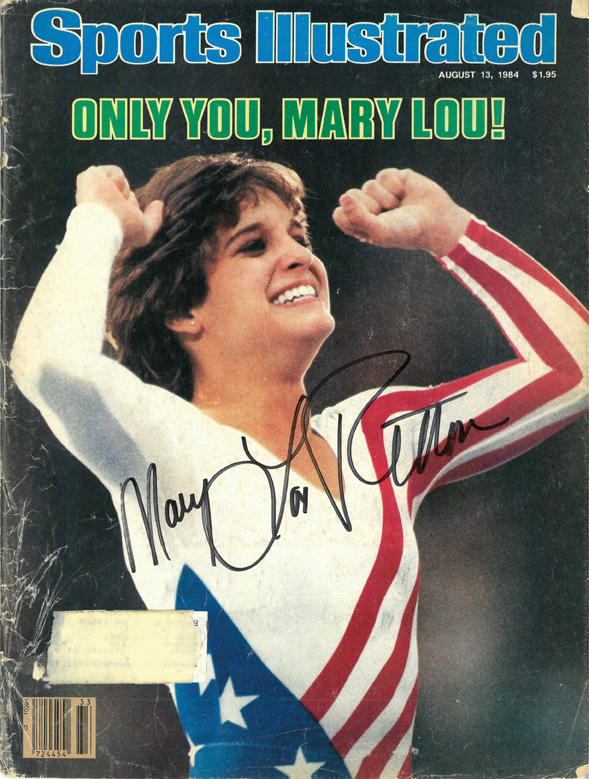

MARY LOU RETTON IN 1984

At this point, a parallel analogy to the art school critique might be useful, such as the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. American gymnast (and Fairmont, W.V., native) Mary Lou Retton had completed all her events for the overall competition, except the vault. She was behind on points by a few decimals and needed to score a perfect 10 in this event to win a gold medal. It was not uncommon for the 4′ 9″ Retton to travel 22 feet in the air during her vault attempts. It was also not uncommon for her to win, as she had done in the Americas Cup, the Cunichi Cup, and the National Championships, all the year before in 1983.

Retton prepped for her first vault attempt, a model of the telegenic athlete, with her pageboy haircut, stud earrings and U.S. Olympic team uniform hugging her body like the wrapping on a Cornish hen. With the concentration of a sniper, Retton churned down the runway, planted on the springboard, floated a full twist and Tsukahara in midair and stuck a perfect landing. The television cameras followed the buoyant Retton as she paced, waiting for the circa-1984 LED screen to display her score. It finally appeared in lights-a perfect 10. Retton appeared jubilant, the crowd burst into applause and Retton’s charismatic coach, Bela Karoly, hooted praise within microphone range. Mary Lou Retton officially became the first American to with a gold medal in the women’s overall gymnastics competition.

It should have been the exclamation point to an amazing story, but then something unexpected happened. Retton returned to the start of the runway and behaved in every way as if she was going to take her second, now unnecessary, vault. She had just played the starring role in one of the most perfect moments in the history of televised sports, but now she was going off script. The TV announcers didn’t know what to make of her behavior. There was no rational reason for her to take her second vault attempt: She had nothing to gain and a great deal to lose in public relations and endorsement opportunities if the second jump fell short of perfection. Retton’s second take-off was slightly more relaxed, but she quickly amped up to full speed, planted her jump and stuck the landing. Remarkably, she scored a second perfect 10.

I watched these events unfold on a flickering television screen in central West Virginia where I grew up. I was far away from the art world then, watching another West Virginian do the impossible in public. It’s a moment I will never forget and one that often returns to mind when discussing the merits of the art school critique. Sports are not often synonymous with art, but the Olympics do provide a convenient corollary. Olympic athletes dedicate their lives toward the mastery of specific skills that provide no immediate measurable function to society other than the entertainment value assigned to specific events that include them.

This does not sound incongruent with much, or even most, contemporary art practice. The Olympic games as we know them resuscitated an ancient tradition with the optimistic breath of 19th-century modernism. In retrospect, the hopes French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin had for the Olympics at the 1892 meeting of the Union des Sociétés Françaises de Sports Athlétiques has been far surpassed. The original members of the Olympic Committee quickly determined that Olympic athletes must be amateurs, removing them from the choppy waters of the professional marketplace while simultaneously showing favor toward the moneyed classes who didn’t need jobs anyway. The Olympic events never needed to justify their own relevance; the very act of performing the events was justification enough. This foreshadows Clement Greenberg’s famous line that the arts “could save themselves…by demonstrating that the experience they provided was valuable in its own right” 4

Monochrome painters or installation artists do not have to explain their commitment any more than Mary Lou Retton did. Olympic athletes presumably do not have critiques, but they do have coaches who get paid to provide assessments and support. Again, the coach is not specifically hired to talk. Coaches are hired to cause improvement.

Retton dedicated her life to becoming a perfect gymnast, even though the task caused duress for her and her family. During the 1984 Olympics, she performed her craft to the best of her abilities and was assessed in real time by a small panel of experts who rendered subjective judgments. And she did all this under the unflinching eye of television cameras for the benefit of the most complex global communication system in the history of the world. It is under these conditions that she prepped for her first vault attempt, and in that moment there was nothing anyone could have said, and no critical conversation, that would have made her perform better. As amazing as her victory was-and it truly was amazing-that is not why I chose her as an example. To perform perfectly under high-pressure conditions is the mark of an efficient, consistent, reliable machine, and a machine that lacks any purpose other than the perfect execution of its task. With her perfect first vault, Retton fulfilled the trajectory that began in the earliest stages of her childhood training. She was a perfect machine.

But when Retton decided to take her unnecessary second attempt in the vault, she had suddenly become inefficient. Her gold medal status was barely minutes old, and she was already risking infamy with another jump. The television crews had already gotten the best footage of the Olympics, but as with O. J. Simpson’s white Bronco ride 10 years later, they could not risk not filming whatever happened next. There was no rational reason for Retton to continue, and no one would have faulted her for forfeiting the second attempt. Retton took the second vault in front of her bewildered audience because in that moment she returned to the mindset beyond the mechanical aspects of her training, that of total joyous irrational engagement with her practice. She stopped being a machine and became an artist. She was perfect a second time in front of a billion people, few who even fully understood the difficulty of what she had done. The second vault was irrational, unnecessary and perfect-like a great artwork. And that’s why I adore her for it.

LYOTARD AND THE INHUMAN

From time to time I am asked to recommend reading lists for artists, and sometimes this even happens as part of a critique conversation. At the top of my list is a small book called The Inhuman by Jean-Francois Lyotard. As a philosopher, Lyotard had reached a level of accomplishment by the 1980s achieved by very few. He was eloquent at moments when his positions ran counter to the “common sense” narratives of science and technology. He placed an ideological canopy over the confusing complexity of contemporary life in “The Postmodern Condition” and for better or worse helped lock the term “postmodern” into common parlance. Throughout the late 1970s and well into the 1980s, his reputation and historical legacy were held to be self-evident. He rode out a seemingly idyllic life of visiting professorships in comfortable locales. His name could be added to the small pantheon of philosophers whose monikers were recognized at all: Derrida, Foucault, Deleuze, Kristeva. If the philosophical world offered gold medals in the all-around competition, Lyotard would seem to have gotten one.

It’s from this position of success that Lyotard wrote his last full book, L’Inhumain: Causeries sur le temps, in 1988. It was translated into English a few years later as The Inhuman: Essays on Time. This was a problematic book, starting as it did in the first chapter from a position resembling speculative science fiction. Lyotard reminds his readers early on of the impending expansion and explosion of the sun that will undo both the planet earth and anyone who might even remember that there was a planet earth. Or as Lyotard states:

“With the disappearance of earth, thought will have stopped-

leaving that disappearance absolutely unthought of.”5

For the remainder of the book, Lyotard postulates the various means by which the trajectory of the earth is governed, all, or in part, by a monadic force of technological complexification he dubs “the inhuman.” The inhuman supports the qualities of the machine aesthetic: increased speed, increased efficiency, consistent outputs, dependence on technology, recording memory and overdetermining future events, among other traits. It’s my belief that the reason art school critiques so willingly gear themselves toward the value system of machines is due in part or in whole from this force described by Lyotard. The trust of the machine aesthetic is not helpful to humans, as it turns out, but mimics the taste and tendencies of the “inhuman.” I am more hesitant than most to pull philosophical writings into the critique environment, and the very last thing I want to do is convert an art school critique into a freewheeling Oktoberfest. However, as a regular practitioner of the critiques, I am frequently reminded of the importance of Lyotard’s thinking and the degree to which the inhuman has entered artistic practice to the detriment of the work. Instead of being prescriptive, I find that I expend more critique time locating the pernicious presence of the inhuman within an artist’s practice and then trying to illuminate it. And this tendency is most prevalent in the descendants, once again, of Sol Lewitt.

THE PROBLEM WITH SOL LEWITT

I’ve already given Sol Lewitt credit for pinpointing a weak spot in the understanding of artistic production, that of fetishizing the singular “perfect” artistic solution. But Lewitt also contributed to another widespread problem by turning artistic practice into a repeatable program. Within the culture of contemporary art, even saying that there is a “problem” with Lewitt approaches heresy. He was, by all accounts, a thoughtful and generous artist who ended his career the way he began it, diligent and respected. In 1969, Lewitt published his “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” and those 35 sentences have become a canonized classic. The publication of the “Sentences” occurred after Lewitt had gained momentum for his modular sculptures and just before the burst of popularity granted him due to his wall drawings. Sentence #5 reads, “Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically” which appears closely linked to sentence #7, which begins, “The artist’s will is secondary to the process he initiates…” 6

The “Sentences” provide not only a mission statement for Lewitt’s own artistic life but also as basic operating instructions for an entire generation interested in the (then) new practice of conceptual art. And since the first generation of conceptual artists found it difficult to sell their work, they took teaching positions in large numbers, where they passed on their value system on to generations of students. It is now also well known that, for Lewitt, the instructions providing directions for the wall drawings are the only surviving artifact from the wall drawing process. It’s the only item that a collector or institution may own. And each time the wall drawing is executed correctly according to the instructions it results in a wall drawing that is in every way equal to all other iterations of that same set of instructions. No individual wall drawing will accumulate preciousness, and every new version is freshly made and eternally temporary.

What Lewitt did, perhaps by inadvertently channeling the machine values of the inhuman, was turn the computer program into a new artistic genre. A series of instructions that produces a determined outcome has always been one of the core principles of computer science, and the history of programming cannot proceed without it. Lewitt may have successfully diminished the problematic practice of fetishizing a permanent art object, but he replaced it with something more damaging: programmed artistic output. When Retton scored a perfect 10 on her first vault attempt, she executed her program perfectly. When she did it a second time for no reason, she was outside her program. This is because the program only calls for her to win the gold medal, not for her to exceed the capacity required to achieve a gold medal.

Time and again I see artists present work in critique that is made manifest through a series of pre-set instructions that they carefully proceed to carry out. And oftentimes, the work receives rote praise because, even in the second decade of the 21st century, Lewitt’s model appears to provide a useful artistic structure, if not an outright ghost sensation of missing functionality. To put it differently, art that is made according to a set of instructions fulfills the function of following those instructions. What I would like to suggest is the opposite: that when artists routinely create a series of instructions instead of a physical artwork they create a situation that anesthetizes their own talent in favor of simulated orderliness. It’s as if these artists demonstrate via their work that they can walk a tightrope of their own construction. But sadly, it’s a tightrope that’s never more than a few metaphorical inches off the ground.

CONCLUSION

It’s difficult to summarize the conditions I prefer in an art school critique without listing the qualities I like the least. I’m wary of the “original sin” notion of student artwork born flawed but with the capacity to be born again thanks to critical conversation. I remain very suspicious of the medical model of diagnosing artwork in order to recommend “cures,” although there are probably times when that’s exactly the right medicine. I find it very important for mentors to realize that silence may sometimes be far more productive than the speech acts they keep in reserve. But most of all, I cast grave doubt on any artistic criteria derived from the language of machines. The speed required from the artistic community itself only adds to the problem by tacitly encouraging artists to be practical, repeatable and fast, when in fact art often requires just the opposite.

As Lyotard states in the first chapter of The Inhuman, “Thinking, like writing or painting, is almost no more than letting a giveable come towards you.” 7 That’s information more fine art students need to hear, because in many cases they may be hearing it for the first time. At the risk of sounding anachronistic, I believe on some level that an artist’s creativity is like a feral animal: Early on it behaves erratically, then with time and discipline it can be harnessed and pulled into uneasy servitude. And like any animal, the more attention and activity it receives the stronger it becomes. The problem then becomes the degree to which artists recognize this internal collaboration with their own creativity and devise ways to live with it. I would suggest that there are times when artistic creativity needs guidance and control, but there are other times when it simply needs time and space to grow. Or again, as Lyotard puts it: “In what we call thinking, the mind isn’t ‘directed’ but suspended. You don’t give it rules. You teach it to receive.” 8

-End-

NOTES

1. Drennen, Craig. “Interview with David Humphrey,” ArtPulse 18. Feb 2014

2. Lewitt, Sol. “Sentences on Conceptual Art.” first published in 0-9. New York. 1969 and Art-Language. England. May 1969

3. Bois, Yves-Alain. “Painting: The Task of Mourning.” from Endgame: Reference and Simulation in Recent Painting and Sculpture. MIT and Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 1986.

4. Greenberg, Clement. “Modernist Painting.” from Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology (edited by F. Fraschina & C. Harrison). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1982.

5. Lyotard, Jean-Francois. The Inhuman: Essays on Time. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington and Rachel Bowlby. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991. p. 9.

6. Lewitt, Sol. “Sentences on Conceptual Art.” first published in 0-9. New York. 1969 and Art-Language. England. May 1969.

7. Lyotard, Jean-Francois. The Inhuman: Essays on Time. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington and Rachel Bowlby. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991. pp. 11-19.

8. Ibid

* This essay was selected for the forthcoming publication ART of Critique: Re-imagining Professional Art Criticism and the Art School Critique, edited by Stephen Knudsen.

Craig Drennen is an artist living in Atlanta and a 2018 Guggenheim Fellow. His most recent solo exhibition was at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Georgia. His work has been reviewed by Art in America, Artforum and The New York Times. He teaches at Georgia State University, served as dean of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and was a board member of Art Papers magazine. Since 2008, he has organized his studio practice around Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.