« Features

Kettle’s Whistle. Objectivity vs. Subjectivity

Did you know that when The Guardian art correspondent paid a studio visit to Turner Prize finalist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye in London last May, two men were loitering outside the building, mobiles in hand, one yelling, “Are you Becca?” at no one in particular? And that in The New Yorker’s obituary for Chantal Akerman, dispersed amongst the list of the filmmaker’s notable achievements, there was a story about the time the writer “paid a visit to her Paris apartment and was offered chocolate from Belgium?” When yet another Guardian journalist met Ben Kinsley to discuss Robot Overloads, the actor remarked how awesome the phone used by the interviewer to record the conversation was in a “mellow and chocolatey voice.” The obsession to talk about recording devices in the course of an interview must be a spreading calamity. Even Rolling Stone, while conferring with the cast of Star Wars: The Force Awakens last December, deemed important to report Harrison Ford’s glances at the twin digital recorders brought for the occasion and how bad he felt once he learned that they “actually used three for Bruce Springsteen.”

It’s been now 46 years since Hunter S. Thompson managed to file a report of the Kentucky Derby for Scanlan’s Monthly without even mentioning the race-a remarkable if unusual exercise in the craft of sports journalism that would soon earn Thompson a seat, next to Norman Mailer and Truman Capote, in the pantheon of those authors masterfully able to describe the events that surround them through first-person subjectivity lens. Indeed, for quite a long time such position was refreshing–the journalistic application of what in physics is known as the “observer effect,” according to whom a degree of participation is necessary in order to develop a full comprehension of the subject. Yet, every great invention always comes with unwanted negative consequences, and the disconcerting, increasing urge contemporary writers have to embellish their facts with distracting decoration seems to point towards a gloomy scenario. The examples mentioned at the beginning are not attempts to furnish the reader with a sympathetic entry point or a moment of identification, but rather indicators of the authors’ desperate desire to star in their own story. It is, of course, possible that an element of self-preservation is involved, with writers focusing on mundane details or venting some kind of familiarity with the subject to give evidence of their presence on the front line. It is also possible that a less defensive but equally well-meant belief that recounting absolutely everything, from the most topical aspects of a conversation to the most insignificant trivia, will help the readership walk away with a full, unpurged picture of the events. Either way, there is no escape that in the vast majority of cases, at least judging from how a lot of broadsheets and periodicals operate these days, what the deployment of this strategy has accomplished so far is at its best the lame journalism that gave us Sarah Thornton’s Seven Days in the Art World, and at its worse those not-too-subtle forms of self-celebration that end up being corrupting, with the author’s sizable ego diminishing rather than heightening the effectiveness of the story.

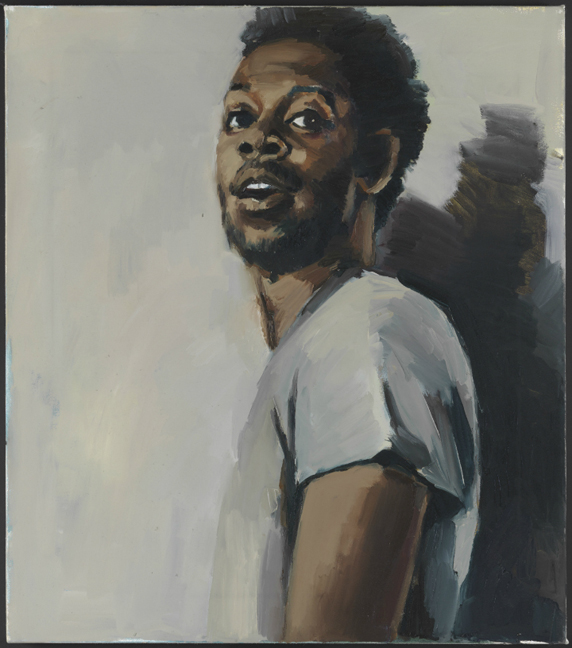

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Radical Under Beechwood, 2015. Courtesy: Corvi-Mora, London and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Copyright the artist. Photography: Marcus Leith, London.

It has been generically stated that journalists’ long-term frustration derives from their constantly dealing with stories and people more important than they are. Cynical as it may sound, to a certain extent it is true. But it’s also unfair. The relationship of a journalist with a story is not so parasitical. Major issues of credibility and responsibility are at stake. The best way to counteract this argument, however, shouldn’t lay in the reinforcement of the “journalist as superstar” concept, but in a serene acceptance that influence is not the same thing as power. Contrary to popular belief, the press doesn’t have the authority to stop wars, impeach presidents, destroy or make careers. What it can do is use its access to privileged and restricted areas to provide insight as well as to reflect growing consensus or disapproval. It can also select and keep stories alive-not a secondary feat in a society steadily dominated by over-information, speed and short attention span. Media in general will never lead public opinions, but they can pace them. Those writers engaged in the process of finding their own voice, rather than succumbing to self-adulation, should happily settle for that.

Michele Robecchi is a writer and curator based in London. A former managing editor of Flash Art (2001-2004) and senior editor at Contemporary Magazine (2005-2007), he is currently a visiting lecturer at Christie’s Education and an editor at Phaidon Press, where he has edited monographs about Marina Abramović, Francis Alÿs, Jorge Pardo, Stephen Shore and Ai Weiwei.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.