« Features

Kettle’s Whistle: Wrapped up in Books

Milan Kundera’s recent request to insert a clause in his agreements to prevent the digital publication of his novels has predictably generated both enthusiastic and perplexed responses, drawing a deeper furrow between those who advocate the uniqueness of the book as object and those who propagate its electronic version as the most practical, in-tune-with-the-times and eco-friendly solution. Upon closer inspection, a few of the arguments from both camps appeared a little naive. Some protested that the author’s right to his work is not extended to the format in which it is published, questioning the readers’ freedom of choice in all this-a process that, as the vinyl/cartridge/tape/CD wrangle that fated the music industry for two decades has amply shown, is often dictated by manufacturers’ rather than consumers’ wishes. On the other hand, Kundera’s stance seems hopelessly anachronistic and brings back memories of the days when the sudden availability of books in malls and megastores irritated those pure souls who thought that intellectual activities of this kind should be limited to designated places such as libraries and mom-and-pop bookshops.

Kundera’s romantic view notwithstanding, these are dreary times for printed papers, and it shouldn’t come as a surprise that an increasingly larger number of artists have focused on the problem. Books have a long history as visual art materials, but whereas in the case of Richard Wentworth, Martha Rosler, Joeb Koelewin, Eva Kotátkova or the Wiener Gruppe (whose installation at the Austrian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1997, consisting of a gigantic pallet featuring hundreds of free, 784-page tomes chronicling the history of the group, still stands as a book-as-art paragon), their presence was fundamentally an acknowledgement of their authority, latest outings such as Pilar Albarracín’s El Asno (2010) or Satch Hoyt’s Say It Loud (Re-creating the Canon) (2012), suggest that this is not the case anymore and that books’ current case history is a lot more critical.

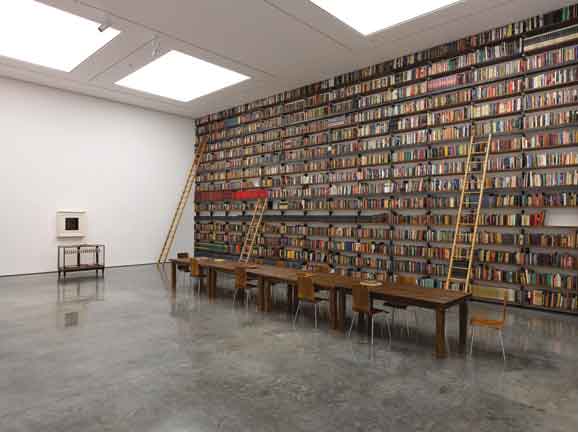

Theaster Gates, My Labor Is My Protest (September 7 - November 11, 2012), South Galleries and 9x9x9, White Cube Bermondsey. © Theaster Gates. Photo: Ben Westoby. Courtesy Johnson Publishing Company, LLC. All rights reserved.

The peak of the discussion was probably reached last summer at Documenta in Kassel, where books were noticeable in all their power and weakness, either as providers of form rather than content (Paul Chan’s series of paintings), treasured objects from the past (Mark Dion’s cabinet) or targets for unexpected vandalism (Matias Faldbakken’s bombed library shelves). Amazon’s report that, in 2011, sales of electronic books outnumbered those on paper for the first time, coupled with Ikea’s announcement that its iconic Billy bookcase had undergone substantial modifications to accommodate ornaments and tchotchkes, is also what inspired Aleksandra Mir to make her Local Library (2012), a monument to nostalgia in which shelves of beautifully untreated, natural wood books, named after illustrious writers in Ikea fashion, (Astrid, Umberto, etc.) tell their etymological/geographical story while marking their symbolical reversion from paper to planks. Massimo Bartolini’s Bookyard (2012), an outdoor collection of books and periodicals stocked in 12 shelves situated in a vineyard near Ghent, that the public is invited to use upon donation, is the proverbial mountain coming to Mohammed, giving visibility to (as well as expanding the possibilities of chance-encountering) a situation no longer so central in the cultural life of a city. More politically engaged but still book-related is also the library Theaster Gates displayed in London on the occasion of his first solo show at the White Cube on Bermondsey Street. Titled My Labor is My Protest (2012), the installation follows Gates’ proclivity for community-engaging and historical investigation as a tool for social change. Borrowed from the archives of the Johnson Publishing Company in Chicago, it offers a comprehensive archive of African-American culture through a selection of books and journals open to consultation, including Johnson’s iconic magazine Ebony (whose back issues from 1959 to 2008 are now tellingly available online for free after an agreement was reached with Google Book Search).

Far from being a trend, these operations nonetheless have at least the common denominator of debating, if not revaluing, an experience that over the past few years many dramatic forecasts have declared on life support. There is undoubtedly a period of readjustment in sight. Book-shaped purses and bookcase wallpapers are an indicator of the common perception of their belonging to a different time and age, as well as how the scale of their objectification is dangerously verging on the decorative rather than the educational. Yet, books have been around for centuries. They offer tactile as well as visual and cerebral involvement, and any technological development, no matter how clever, is unlikely to squash them for good.

Michele Robecchi is a writer and curator based in London. Former managing editor of Flash Art (2001-2004) and senior editor at Contemporary Magazine (2005-2007), he is currently a visiting lecturer at Christie’s Education and an editor at Phaidon Press, where he has edited monographs about Marina Abramović, Francis Alÿs, Jorge Pardo, Stephen Shore and Ai Weiwei.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.