« Features

Kettle’s Whistle: Manchester, England

On June 15, 1996, the Irish Republican Army detonated the biggest bomb ever inflicted upon the U.K. during peacetime, this time in Manchester. Placed in a Ford Cargo parked on Corporation Street, police first became aware of the explosive after an anonymous phone call to the local TV station Granada, giving them less than an hour to evacuate an area crowded by more than 70,000 people. The bomb eventually blew up around 11 a.m., destroying one third of the city’s retail space and injuring more than 200 people despite a mile-and-a-half-wide area being blocked off.

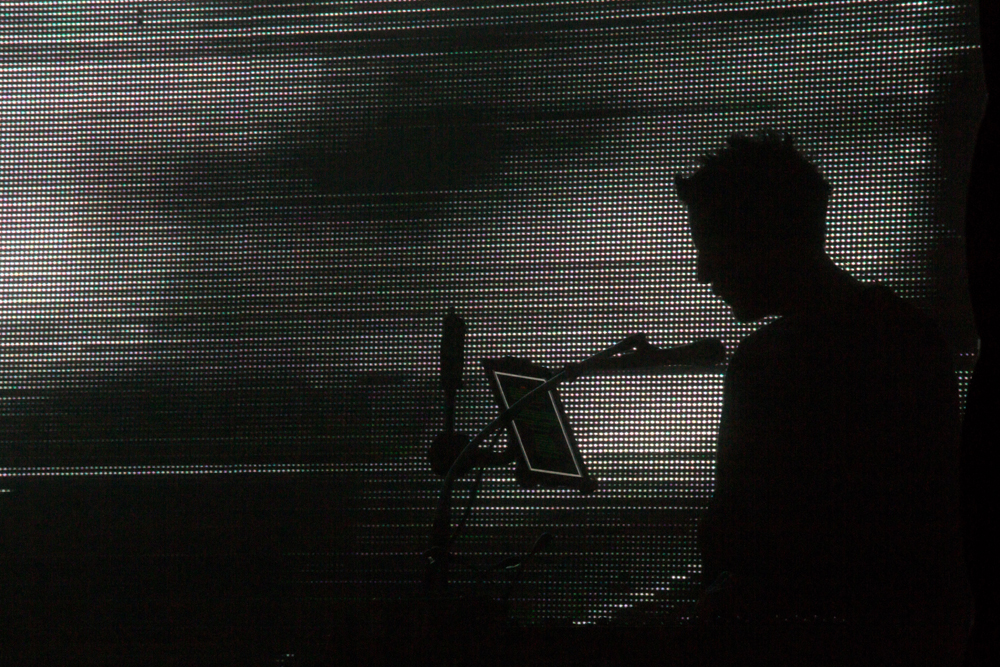

I remember walking around the devastated and desolated neighborhood in the aftermath and the deafening silence permeating what used to be vital streets and buildings now reduced to empty shells. Partly because of their magnitude, and partly due to their sudden, unexpected appearance, those images of destruction and violence left a deep mark, to the extent that even more than 15 years later, they inevitably resurface somewhere in the back of my brain every time I’m in town. This is what happened last July too, on the occasion of the biennial Manchester International Festival. Now in its fourth edition, the festival, directed by Alex Poots, has emerged over the years as a crossover event in which visual arts, music, film and theater not only happily live together but occasionally amalgamate with startling results. This year’s highlights were Massive Attack vs Adam Curtis at Mayfield Depot, where the trip-hop band performed behind a series of gigantic screens with music and images finally going together rather than just having the first underscoring the mood of the latter; Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler’s sneak preview of River of Fundament, Barney’s anticipated return to film 10 years after the Cremaster Cycle; Tino Sehgal’s reproposition of This Variation, his successful work at documenta last summer; Dan Graham’s temporal performance Past Future Split Attention; and “Do It 2013″ at the Manchester Art Gallery, the latest version of the groundbreaking exhibition conceived by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Christian Boltanski and Bertrand Lavier, entirely composed of artists’ instructions to be interpreted anew every time the show takes place.

Massive Attack v Adam Curtis. Manchester International Festival, July 4 – 21, 2013. Photo: James Medcraft.

Although the rich program regularly captures an out-of-town audience that makes the festival live up to its name, the MIF, as it is now familiarly called, hasn’t been immune to a series of criticisms, chief amongst them its failing to establish a fruitful dialogue with some of the local institutions. This is a common issue for all macroscopic initiatives happening in allegedly peripheral cultural destinations, and hopefully one that will be refuted or corrected soon, because Manchester, a Northern industrial city mostly reinvigorated by a vibrant football and music scene as well as the third largest Chinese community in Europe (a remarkable feat considering that we are talking about a metropolitan borough with an estimated population of 500,000), has indeed plenty to offer, as a walk outside the traditional venues of the festival would have indicated.

There is the Whitworth Art Gallery at The University of Manchester, for example, the art museum created by the late Robert Darbishire inside a public park before the Serpentine Gallery had even been invented, currently waiting for the completion of two new wings designed by MUMA due next year, and defined by a program both built around its collection and the commission or acquisition of new work, such as Pavel Büchler’s confessional/archival work Idle Thoughts or Alison Wilding’s significant sculpture Deep Water. Cornerhouse, arguably one of the most dynamic art institutions in the U.K., hosted “Anguish and Enthusiasm,” a group exhibition analyzing post-revolutionary scenarios where Pocas Pascoal’s splendid film on the independence of Angola, There Is Always Someone Who Loves You, and Michelangelo Antonioni’s documentary on Mao’s Cultural Revolution, Chung Kuo China, stood out.

The Chinese Arts Centre, a serious organization devoted to the promotion of Chinese art founded way before this became a market trend, had Lee Mingwei’s moving The Quartet Project, an empty, dark room filled with flickering lights and sounds from four different sources, each playing a part of Antonin Dvorak’s American Quartet, a composition in which American spirituals and classical music merge to generate a profound feeling of homesickness, in an installation that overall seems to act as the perfect counterpoint to Sehgal’s piece. On a more grassroots level, the Rogue Artists’ Studios & Project Space introduced the performance work of Rosie Farrell and the multimedia installation of Chris Paul Daniels about the tumultuous political landscape in Kenya that the artist documented during a residency in Nairobi. Within the limited time window and hectic schedule of the festival it was only possible to scratch the surface of what the city had in stow, but even so, there was plenty to see for the imaginative spirits willing to venture outside the bubble.

There were fortunately no casualties on that nefarious day in June 1996. It is refreshing to see that still standing and being counted with the rest of the population who survived that dreadful experience is also the spirit of Manchester.

Michele Robecchi is a writer and curator based in London. A former managing editor of Flash Art (2001-2004) and senior editor at Contemporary Magazine (2005-2007), he is currently a visiting lecturer at Christie’s Education and an editor at Phaidon Press, where he has edited monographs about Marina Abramović, Francis Alÿs, Jorge Pardo, Stephen Shore and Ai Weiwei.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.