« Editor's Picks

LUIS CRUZ AZACETA: MUSEUM PLANS SERIES

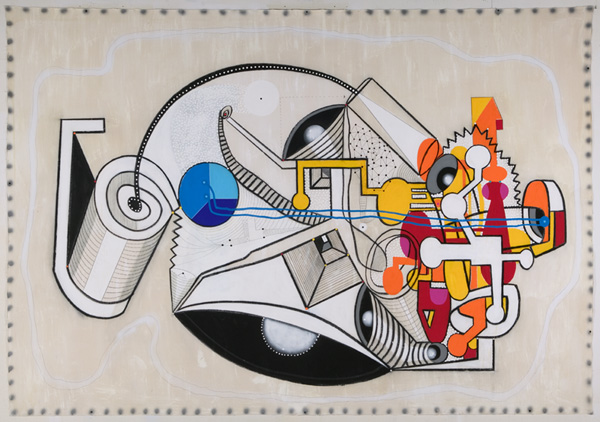

Luis Cruz Azaceta. Current Museum Plan, 2007. Charcoal, acrylic, enamel, shellac on canvas, 82" x 122". Courtesy of the artist and Bernice Steinbaum Gallery.

Luis Cruz Azaceta (Havana, 1942) is an artist whose work carries the indelible imprint of displacement. The solitude, cultural and linguistic isolation, and the certainty of no longer belonging anywhere has marked his view of the world since he immigrated to the United States from Cuba at the beginning of the sixties. Throughout his career, his works have continually exuded that feeling, whether veiledly or explicitly. His perspective is that of a displaced individual attempting to find a personal route in the midst of that strange labyrinth that is identity.

Nevertheless, in spite of having experienced exile firsthand, his work is not contaminated with the stereotypes we tend to find in many Cuban artists. In an interview with Edward J. Sullivan in 1998 on the occasion of his exhibition, “Bound,” in New York, Luis Cruz Azaceta would state: “What I try to do in my work is to go from the particular to the universal statements.” This strategy is precisely what has saved him from the ordinary and has allowed him to gain important standing within the mainstream of contemporary American art.

His work sketches the experience of being uprooted, not confined to any specific place or time; rather, it is elevated to a universal plane. His series, “Museum Plans,” shown at the beginning of this year in Miami, at Bernice Steinbaum Gallery also comes from his desire to give rise to “… ephemeral creations in need of permanence, looking for a home to dream.” (1) The series emerged around 2005, while the artist was Chair of Art at the Lamar Dodd School, University of Georgia (Athens, GA). At that time, he participated in the process of creating a museum.

The experience of participating in the design of a museum, which ended up not satisfying the needs of the artistic community, but rather responding to the criteria of university administrators, led Luis Cruz Azaceta to view the museum as an institution that encapsulates objects of value and legitimizes them within the cultural establishment. This may be an entity whose curatorial and museological criteria do not always respect the needs of the public or the quality of the artistic creation, but may instead respond to other demands - political, economic, etc.

Museum Plans revolves around the concept of the museum as a “container of culture and knowledge.” This is the traditional view deeply rooted in western society that has come under harsh attack by the avant-garde movement and contemporary art. (2)

Cruz Azaceta decided to break with this paradigm and create imaginary museum plans as a means of legitimizing the people or places he admires and desires to perpetuate. These are projects that laugh at the stereotypical concept of the museum, and that, at the same time, are works which, instead of being traditional neutral boxes “containers of culture,” are personalized, organic, monumental and unrepeatable forms.

This series, Museum Plans, has its formal and conceptual origins in earlier pieces, such as, “Ear” (2005), a work that is a kind of voyage into the interior, not of any particular individual, but rather traveling beyond, into the interior of culture, to investigate it and absorb what it is capable of contributing. Another work that precedes this series is “Air Carrier,” also from 2005. This painting portrays the front part of a passenger airplane whose interior is full of sinuous highways and paths, metaphors for that never-ending voyage of comings and goings, trips, the eternal quest for a port. These themes are a constant in his work, nurtured by experiences lived by the artist at the inception of Museum Plans. In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina lashed New Orleans, the city in which Cruz Azaceta had been living since the beginning of the 90s. The artist and his family lived moments of great uncertainty about the future of their home, his studio, their belongings. Another new exile thus began for the author, who for a time commuted between Baton Rouge and Georgia.

The museum plans conceived by Luis Cruz Azaceta at that time maintain the labyrinths that appear in the two works from 2005. The labyrinth is seen as an infinite voyage because in the end it can all be summarized as leaving, migrating, adapting, searching, scavenging, whether it be in the heart of a culture, a place, or the human mind. The transgressive intention of the artist with this series goes beyond the proposal of the labyrinth. He incorporates toys (airplanes, helicopters, small trailer trucks, autos), thereby adding a ludicrous and irreverent element that contrasts with the aura of solemnity traditionally associated with museums. In his museum plans, the keen eye can also find sexual organs, breasts and buttocks, hidden in the tangle of lines. These are totally unexpected elements, which veiledly allude to the aura of seduction surrounding these institutions.

His plans, dedicated to Reinaldo Arenas, the City of Miami Beach, Havana, Edison, Bukowski, Kafka, the architect, Frank Ghery, Louis Kahn, among others; are unique works, whose forms refer symbolically to each one of the dedicatees. For example, the plan dedicated to Reinaldo Arenas contains a computer chip whose wires have been severed in allusion to the tragic life and the terrible end of the talented exiled Cuban writer. The plan of Miami Beach, on the other hand, exudes liberty, dynamism and color, just as the artist visualizes the city. For its part, the plan dedicated to Thomas Alva Edison displaying geometric and rational forms, with an amalgam of wires and computer chips. The work displays luminous and vibrant colors, in allusion to the creative mind of the celebrated inventor.

With Museum Plans, Luis Cruz Azaceta once again demonstrates an enviable ability to analyze culture and society. As in the seventies and eighties, he has been able to capture the frail nature of society in his series about subways, AIDS victims, the Vietnam War, or in his series on the social phenomenon of Cuban rafters at he beginning of the nineties . He now has the sensitivity to see the pitfalls and difficult aspects of the individuals and institutions who govern culture, and he is able to brilliantly express them in those labyrinths of lines devoid of exits.

The artist is currently working on an installation that he will present in autumn at PROSPECT 1, the New Orleans Biennial. This installation is related to a series that the artist has entitled POST-KATRINA, on which he worked at the same time as the series Museum Plans, since September 2005. The POST-KATRINA series assembles sculptures, installations, photo-collages, drawings and paintings. In this respect the artist comments: “It is like art in ruins, (…) a total fragmentation of the city in the aftermath of the catastrophe.” These are pieces in which he has incorporated objects found after the natural disaster. In these works he combines bottles, wheelchairs, pots, photos, newspaper fragments from that time, which comment on what transpired. His aim is to awaken social conscience and compassion about the horror of this event and joint efforts to revitalize the city.

The oeuvre of Luis Cruz Azaceta has been exhibited in notable museums and institutions, such as: the Museum of Modern Art, (New York); the Smithsonian Institute, (Washington, D.C.); The New Museum of Contemporary Art, (New York); the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, (New York); Indianapolis Museum of Art, (Indiana); Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, (Massachusetts), to name a few. Throughout his career he has received numerous grants including the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Grant. His pieces form part of recognized private and public collections, such as: the Houston Museum of Fine Arts; the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York); the Miami Art Museum; the Museum of Fine Arts, (Boston); the Museum of Modern Art, (New York); Museo de Bellas Artes de Caracas, (Venezuela); Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey MARCO, (Mexico); among others.

Notes

(1) Excerpt from the artist’s statement (December, 2007) on the occasion of the Museum Plans exhibition.

(2) Reference is made to the futuristic 1909 manifesto in which Filippo Marinetti called museums and libraries “cemeteries” or Marcel Duchamp’s revolutionary proposal in his “Boite en valise” (1936-1941)

Raisa Clavijo: Curator and art critic. BA in Art History (University of Havana, Cuba), MA in Museology (Iberoamerican University, Mexico), Former Chief Curator of Arocena Museum (Mexico). Editor of Wynwood. The Art Magazine.