« Reviews

Miamicito

Dot FiftyOne Gallery - Miami

By Raisa Clavijo

Dot FiftyOne gallery recently hosted “Miamicito,” an exhibition assembling the works of fifteen contemporary Bolivian artists. The show, which was organized by Kiosko Gallery of Santa Cruz, included the works of: Alejandra Alarcón, Ramiro Garavito, Gastón Ugalde, Roberto Valcárcel, Douglas Rodrigo Rada, Raquel Schwartz, Alfredo Román, Roberto Unterladstaetter, Cecilia Lampo, Eduardo Ribera, Alejandra Delgado, Keiko González, Claudia Joskowicz, Oscar Barbery, and Andrés Bedoya.

“Miamicito” takes its name from Bolivian flea markets where countless products are sold, from perishables and domestic items of basic need to clothing, electrical appliances, and often imported contraband merchandise. The “miamicitos,” in which tradition and modernity, the native and the foreign coexist, symbolize the complexity and diversity of modern Bolivian society.

As noted in the curatorial statement, this exhibition “presents the audience with the idea of a heterogeneous syncretism, the timeless matter of the moving spirit of times. That essence, which debates the pretentious and hybrid [global] identity, and the need of [self] assurance.” Thus, “Miamicito” exhibits works that constitute a diverse sampling of contemporary Bolivian art. Many topics are addressed; among them are those that allude to the current political scene, the complex social framework, ethnic and racial tensions, genre conflicts, reflections on the nation’s history, both past and recent, as well as the climate of social hopelessness and inconformity remaining in the country.

Of note among the exhibited works is Woven Channels (2009-2010) by Raquel Schwartz. The piece consists of a 60-foot long “cloth” meticulously woven out of hundreds of audio-cassette tapes. The creation of the piece began with the recollection of used tapes, mostly acquired from various street markets. The collection includes tapes of traditional indigenous music and popular music as well as those of sermons by Christian pastors, who have gained many followers in Latin America. The work becomes a kind of compilation of the “audible memory” of a country that simultaneously struggles with ancestral tradition, cultural hybridization, and the unstoppable road to progress. Woven Channels is also a reflection on time. The artist contrasts the duration of the work processes (the manufacture of the tapestry and the gathering of the material) with the speed with which today’s music and technologies emerge and then fade away.

Gastón Ugalde, Aparapita, 2010, mixed media and coca leaves, 47” x 19.” Photo: Mariano Costa-Peuser.

Gastón Ugalde, one of the most internationally renowned Bolivian artists, displays a poster-sized collage depicting a $100 bill made with coca leaves. The piece creates a parallel between the coca leaf and the currency of the United States, destination par excellence of the cocaine that comes from South America; however, it also constitutes a metaphor for a thriving and emergent social class in Bolivia associated with the production and trafficking of narcotics. Ugalde has integrated the coca leaf in his work for some years now. The coca leaf, which holds a ritual connotation for indigenous people and has been used traditionally as sustenance and for medical purposes, has been manipulated for political ends by the current populist government that presents it as a symbol of identity.

In her urban landscapes, Cecilia Lampo also addresses the redefinition of the country’s social structure from the perspective of the emergence of a thriving, prosperous social class, whose wealth comes from the trafficking of all types of products or from its relationships with the government. It is a social class that is changing the urban landscape with buildings erected with complete disregard for codes and standards. These hybrid structures proliferate and respond to the social reinforcement interests of their owners.

In his oeuvre, Roberto Valcárcel criticizes the aesthetic and moral standards, which govern not only art but also the art market in Bolivia. With a deliciously ironic sense of humor, Valcárcel presents black surfaces on which the pictorial scene has been substituted by barely legible descriptions written with dark vinyl letters. His oeuvre winks mockingly at what is commonly consumed as art in a country in which many who can acquire it lack aesthetic knowledge and where study programs at art schools respond to nineteenth century artistic codes or cling to the language of early twentieth century Mexican muralism.

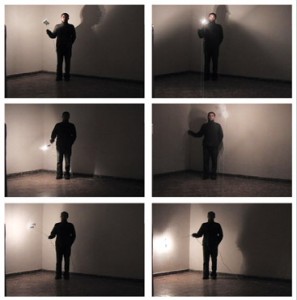

For its part, the video Foco (2003) by Douglas Rodrigo Rada is a reflection on individual achievement and the limits a subject confronts in his quest. In a small, dark cubicle, the artist spins around a light bulb hanging from a wire. The light’s spectrum is widened as he slackens the wire. The action ends when the light bulb breaks against the wall and he once again finds himself in the dark.

Claudia Joskowicz presents a video trilogy that reflects on the figure of the hero and how popular imagination mythically deconstructs historic events, altering their original meaning. In Round and Round and Consumed by Fire (2009), the artist alludes to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’s confrontation with the Bolivian army in their hideout near San Vicente. Historic chronicles record the death of the two outlaws during this confrontation in 1908; however, the details of the event were never verified. With very slow panoramic camera movements, the artist records apparently superfluous details about the place where this historic event is said to have occurred, as a metaphor for the impossibility of recreating an accurate narrative of the event.

In Drawn and Quartered (2007) she reproduces the public execution of Tupac Katari, leader of the indigenous rebellions against the Spanish colonial government, in 1781. The artist appears to freeze the tension and violence implicit in this deed by showing a sequence of shots that include the architecture, the pavement, the motorcycle wheels that have substituted the horses in the video as instruments in the drawing and quartering, as well as details of the hero’s face and body.

Vallegrande, 1967 (2010) completes the trilogy, recreating the scene after the death of Ernesto Guevara as it was broadcasted by the media at that time. The camera presents shots of the corpse in a prone position and concentrates on recording details of the site such as the vegetation and graffiti that has been left over time by admirers of the guerrilla leader in this place that has become a tourist destination for the Left. With this trilogy, the artist questions how lapses, omissions, ambiguities, and manipulations present in historic narratives create a distorted image that ends up prevailing as valid in the minds of the people.

“Miamicito,” with no greater pretense, seeks to show the permanent intersection of the territorial, conceptual, and disciplinary limits that characterize contemporary Bolivian art. This selection of works translates the artists’ stand towards their reality and their uncertainty about what the future holds.

(April 9 - June 5, 2011)

Raisa Clavijo is an art historian, critic, and curator residing in Miami. She is the editor of ARTPULSE.

Filed Under: Reviews