« Features

Tomás Ochoa: Social X-rays

The work of Tomás Ochoa (Cuenca, Ecuador, 1969) carries an implicit, powerful political message. This multidiciplinary artist takes Latin American society and history as essential raw material, analyzing them in light of his knowledge of semiotics, post-structuralist theories and decolonial discourse. His strategy is based on dismantling or deconstructing “official” history, that version of historic events as told by the victors and whose narration and interpretation is profoundly contaminated by the neocolonial perspective that has characterized the discourse of modernity. Ochoa is not content with retrieving documents and photographs and intervening them; instead, he deconstructs and analyzes these representations in today’s light, using them to understand the complex social reality in which the world of today lives, not only in Latin America, but also in any other area where riches and access to opportunities are unevenly distributed.

Tomás Ochoa, From “Flores de ceniza” series, 2012, gunpowder on canvas, 10 couples: each 23.6’ x 23.6”. All images are courtesy of the artist and The Americas Collection, Miami.

Ochoa is self taught; his education has been nourished by his studies of literature, philosophy, anthropology and semiotics. He discovered that the study of language and symbols is an essential tool for understanding the codes through which to comprehend the past as much as the present and their forms of representation.

He identifies and emphasizes specific events that occurred in the recent past, or that are part of daily reality, singling out the event in question to build it into a pretense in order to analyze themes of wider reach, like the effects of war (Paraíso. Línea negra, 2016); the racism enclosed in the consciousness of the contemporary individual (Pecados originales, 2012); the drama of emigration (Multitud and La casa ideal, both from 2008); forced human displacements disguised under the false promise of “progress” (6MM3. El cuarto oscuro, 2003); the manipulation of history by those who have the power to write it (SAD CO, The Blind Castle, 2003); the neocolonial politics that imply a political division of the world into north and south; the developed and underdeveloped worlds, among other themes. Ochoa critically reviews the official version of the historic past in order to retrieve those accounts that have been erased or altered, provoking interpretations in which modernity and colonialism, local and global realities overlap. His work puts the finger on utopian promises unfulfilled by modernity, whose impact has slowed the development of numerous social groups for many generations, above all in South America, a continent whose reality he knows very well.

His fundamental source is archival photography, which he takes as a referent to create paintings, intervened photographs, videos and installations. Above all, photography constitutes a cultural product. Not in vain did Howard Becker say that, “Photography has been used as a tool for the exploration of society.” (Becker 1974). Ochoa, upon appropriating and recontextualizing it in the present, rewrites in contemporary code a new story, a kind of palimpsest, whose different layers of meaning reveal diverse circumstances, names, human beings and events that coexist amongst themselves and are brought up to date in order to reveal the fact that the history of society is often written over time, over and over again, in different codes, but with similar connotations.

Ochoa’s interest in time and history was already apparent in series like Fractales, produced in the 1990s. “Fractals,” for Ochoa, for the manifestation of objective time. “Time does not have the same meaning if we apply it to nature than if we relate it to man. Natural time is objective and measurable; man’s time is a subjective and heterogeneous experience.”1 These series of abstract expressionist paintings have been revisited by the artist at various moments in his career. Fractales have happened thanks to chance; Ochoa has allowed the pigments, the thickeners, the water and the days to follow their natural course, to do their work, allowing the pictorial material to flow over the canvas.

In the paintings of the series Devenir Animal, based on the theories of Gilles Deleuze and produced at the end of the 1990s, Ochoa makes the images of the bodies and faces of day laborers, who walk about desperately seeking work in the Plaza de San Francisco in Cuenca, coexist next to drawings of indigeneous people and conquistadors from the 16th century created by the Dutch artist Theodor de Bry (1528-1598), who represented an America that he never visited, based on the chronicles of members of European expeditions. Ochoa compares the lot of these hopeless day laborers, who find themselves in the bottom layer of the social pyramid, with the destiny of guinea pigs, cruelly sacrificed by man, whether for domestic consumption or in the name of science and progress.

Tomás Ochoa, SAD CO. The Blind Castle, 2003, video, three channel, color, sound, 25 min. 44 sec., installation view.

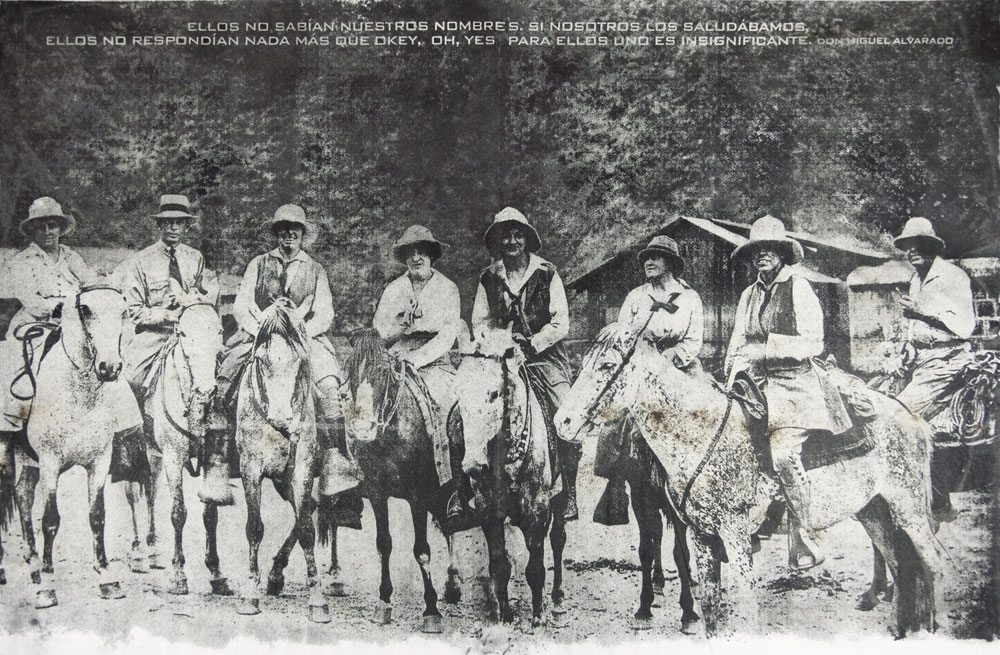

SAD CO (The Blind Castle), the installation that he presented at the Venice Biennial in 2003, includes video, photography and interviews with four former miners of the town of Portovelo in Ecuador. The piece analyzes neocolonial relationships by exploring collective memory. The video presents “live documents,” or testimonies of the miners who told, as though seeking compensation for the exploitation they suffered, of how they “stole” small grams of gold from the company, slathering mud from the mines containing metal particulates on their bodies. The work retrieved photographs taken by John Tweedy, one of the managers of SADCO, that constitute the sugar-coated and official version of life in the mine, documents that he later intervened and recontextualized for the mise en scène of the piece that analyzes neocolonial relationships and the resistance strategies of the defeated.

Ochoa revisited these photos in 2010 in the series Cineraria, in which he enlarged the images and substituted the film grain with gunpowder. When the powder is burned, it leaves an imprint of fire and ash on the new support. The act of burning the images could be interpreted as a cathartic experience; however, Ochoa resizes the symbolic connotation of the photos upon exacerbating memory through the action of the fire.2

Tomás Ochoa, Paraíso. Línea negra, Valle del Guejar, 2016, gunpowder on canvas, triptych, 94.48” x 141.7.”

The gunpowder is also utilized in series like Libres de toda mala raza (2013), Flores de ceniza (2013), Pecados originales (2012) and Paraíso. Línea negra (2016). The first three series call attention to the effect of neocolonial politics. In Pecados originales, Ochoa takes archival photographic images from the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, related to the geodesic and ecclesiastical missions that took place in Ecuador during this period, aimed at classifying the “new species” that inhabited the recently discovered regions. These images show the colonial regard, tied to racial theories and the exoticism that characterized documentary evidence collected by the members of European expeditions. The artist exposes the discourses coming from the West that produced a fictitious and above all exclusionary set of beliefs from which the identity and image that we ourselves have as Latin Americans has been constructed. The use of archival photographic images points to the idea of the image as a document of memory, but at the same time as a vehicle to alter memory and historic facts insofar as the fact that the image is taken from the perspective of the author of the photo. Ochoa allegorically substitutes film grain with gunpowder, just as he also replaces the lines of the maps of said expeditions. With this gesture, he redefines images that upon being burned evoke the violence implicit in the colonial processes and in the way of thinking in which racial division and social stratification imposed since the early moments of the colonization of the New World, and that still survive to this day, are firmly rooted in the models of representation and valuation of individuals.

Flores de ceniza is based on a similar idea, highlighting the colonial modes of representation and the way in which this ideology survives in the model of self-representation. Once again, the artist has utilized documents that prove the eagerness of the colonizers to classify, while at the same time he presents photography, painting and gunpowder with an allegoric meaning. Ochoa reproduces the illustrations of Flora Peruvian, the first book on natural history produced in the Americas, and on them he superimposes the faces of young “cholas” (indians and mestizas) taken on the streets of Cuenca, in September 2012. With them, he attempts to destabilize the canons of beauty of a society of clearly indigeneous ancestry, but which endeavors to emphasize its European blood. For its part, Libres de toda mala raza takes its title from history textbooks in the region of Antioquia, Colombia, which make clear how the colonial remnants persist in the modern construction of the concept of a “nation,” thereby legitimizing themselves as historic sources. Ochoa takes as reference portraits taken at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries in Antioquia by the photographers Melitón Rodríguez and Benjamín de la Calle. The artist called together passers-by at the Botero Plaza in Medellín and took photographs of them copying the poses used by these Antioquian photographers, using as a backdrop one of the backgrounds used by them. Then he transfers both the current photos and the old ones to the canvas, and he once again substitutes film grain with gunpowder. In this way, the artist attempts to destabilize from the frontiers of art the representational structures that exclude and lead to an attitude of subordination.

Paraíso. Línea negra (2016) alludes to the drama of the prolonged war that in Colombia, his current country of residence, has claimed thousands of lives. The work is based on the action that in March 2003 a group of Arhuacos took, going through the base of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, crossing dangerous areas under paramilitary control, symbolically tracing a border that they called “La Linea Negra.” This incident was picked up by Stephen Ferry in Violentología (Icono Editorial, 2012). This rite with ancient roots became political action. “During the following decade their strategy managed to reduce violence and strengthen the indigeneous control of the territory.”3 This project revisits the action of the Arhuacos, going over and documenting images of different places in the country that have been battered by violence and war. As in previous works, Ochoa has substituted film grain with powder that when burned sticks to the surface. Paradoxically, these locations have been safeguarded from the destructive advance of man in the name of progress and modernity, thus preserving the equilibrium of ecosystems. The gunpowder in the work of Ochoa can be interpreted as a metaphor for the act of manipulating critical, delicate information that could “explode” at any moment.

An analysis of this artist’s work displays the way in which he identifies and intervenes the evidence of the historic event, in this case the image; deconstructing its semantic structures in order to identify its relationship with the social context in which it arises; and examining its role in the historic moment in which it occurs, but also in order to visualize the manner in which it affects the construction of the social ideologies of the present. His research and decoding of the testimonies of the past produce as a result keen social X-rays. The moments immortalized in his work provoke, challenge and seduce in the manner indicated by Barthes in La cámara lúcida.4 They are that punctum that stabs, disturbs, confronts, that “vanishing point,” which draws back the veil surrounding truth and invites us to investigate it.

Notes

1. Tomás Ochoa. Espejos con memoria. Quito, Ecuador: Produbanco. Grupo Proamérica, 2014, p. 11.

2. Ibidem p. 111.

3. Ferry, Stephen. Violentology. Bogota: Icono Editorial, 2012.

4. According to Barthes, the “studium” alludes to the deconstruction and contextual analysis of an image, to its relationship to history and society; and the “punctum” has been understood as that component contained in every image that provokes, that calls attention, a kind of jab that constitutes a “vanishing point,” that space in which the field is open to sharper questions that are linked to a greater or lesser degree with the human being.

Bibliography

- Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 2010.

- Becker, Howard. “Photography and Sociology,” in Studies in the Anthropology of Visual Communications, N.1, 1974.

- Quijano, Aníbal. “Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina,” in La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas Latinoamericanas. Edgardo Lander. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, July 2000.

Raisa Clavijo is the editor-in-chief of ARTPULSE. She is an art historian, critic and curator based in Miami. Clavijo has a B.A. in art history from the University of Havana and a master’s degree in museum studies from the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City. Former chief curator at Museo Arocena in Mexico (2002-2006), she founded Wynwood: The Art Magazine, in Miami, where she worked as editor from 2007 to 2009. In 2009, she founded ARTPULSE and ARTDISTRICTS magazines.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.