« Features

Mythic Magic And Morbid Memory: Roberto Fabelo’s Visionary Fantasies

By Donald Kuspit

Now I challenge anyone to explain the diabolic and diverting farrago of Bruegel the Droll otherwise than by a kind of special, Satanic grace. For the words ‘special grace’ substitute, if you wish, the words ‘madness’ or ‘hallucination’; but the mystery will remain almost as dark….and I cannot restrain myself from observing (but without pretension, without pedantry, without positive aim, as of seeking to prove that Bruegel was permitted to see the devil himself in person) that the prodigious efflorescence of monstrosities coincided in the most surprising manner with the notorious and historical epidemic of witchcraft. Charles Baudelaire, Some French Caricaturists 1

The Devil is the symbol of evil….he has a multitude of shapes at his disposal, yet always remains the Tempter and Tormentor. His fall from grace is symbolized by his debasement into animal shape. The Devil’s entire purpose is to deprive humans of the grace of God and to make them yield to his control. Dictionary of Symbols 2

A man is only as big as the diabolic in himself he can assimilate.

Paul Tillich

What is one to make of Roberto Fabelo’s wide-ranging art, with its different subject matters-human faces and figures, animals and inanimate objects, sometimes all thrown together, sometimes synthesized into hybrid monsters-and different methods, ranging from the use of found objects in installations to delicate linear drawings, exquisite watercolors, and painterly works, sometimes on canvas, sometimes on cardboard, sometimes on wood, sometimes on fabric? Fabelo can be meticulous, scrupulously attending to detail, and intensely instinctive-passionately expressionistic–in his handling. The extremes sometimes converge, uneasily yet convincingly. Fabelo’s technical mastery is self-evident-he is the master of every medium he touches-and so is his morbidity: it is the common emotional thread in the vast tapestry of visionary works he has created. He is technically, materially, formally astonishingly versatile, but he is emotionally single-minded: he is obsessed with the innate absurdity-dare one say madness, as his recurrent series of Mad Portraits (2003, 2004, 2006, 2008) permits us to do-of human beings, more broadly society as a whole. For Fabelo both are irreparably malformed-damned and doomed in emotional hell.

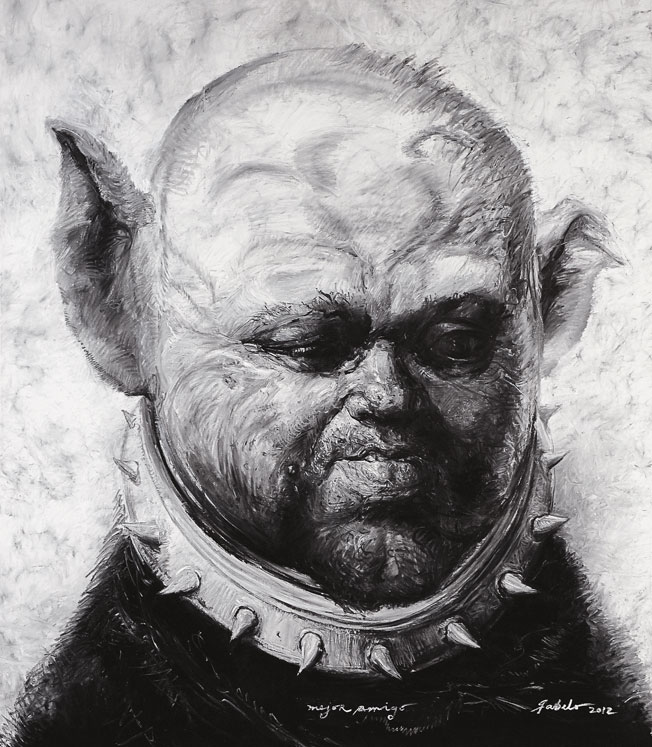

Fabelo has what Baudelaire called that “prodigious talent for the grotesque and the horrible” that is the sign of modern imaginative genius. For Baudelaire, who found it above all in Edgar Allan Poe’s stories and poems-which is where the morbid Symbolist Odilon Redon also found it-it releases the artist from the chains of didactic classicism. Rebelliously permissive, it allows the free play of critical fantasy–fantasy that uncovers the diabolical truth about people and society. Like all the great modern fantasists, Fabelo shows, with a Goya-like vehemence that epitomizes the ambition of all of them—from Bosch and Bruegel through Redon and Ensor to Picasso and the Surrealists–that human beings are more sinister, not to say devilish and insane-diabolically mad, possessed by the devil, insidiously evil—than they appear to be on the surface. The figures wearing helmet-like birds’ beaks in the series A Bit of Us (2008)-they appear also on the heads of some of the figures in the Mad Portraits-have their precedent in Bosch’s hellish scenes. One figure has a beak-like mask, as though participating in a Venetian carnival, another has a dog’s head for a helmet, others pointy snail shell helmets, still others with the ceremonial type Attic helmets worn by warriors in some Renaissance paintings: all convey their belligerence and brutishness. Identifying with animals, they have become devils, perhaps most explicitly in Fabelo’s tempting mermaids, bewitched and bewitching sirens-the Main Dish (2002) as one of his works declares. The point is made explicitly by the large portrait of a man with devil’s ears that dominates the far-right panel of A Bit of Me.

The title suggests that Fabelo doesn’t exempt himself: he’s a host of demons, if not the devil incarnate. One can read this confrontational masterpiece from left to right-each of the eight panels is in effect a page in a picture-book displaying the damned in all their infinite variety-or be drawn into it anywhere by staring into the eyes of any of the many figures that stare at one. Their faces mirror one’s own inner face. It has been said that the spectacle is an expression of false shallow consciousness, but Fabelo’s spectacle of the mad-worthy of Goya’s maddening spectacles of the emotionally damaged in his so-called Black Paintings—shows that it can tell the deep emotional and social truth. Goya depicted the social madness of war and religion, as though without them human beings were sane, but Fabelo shows that everyone is born mad: madness is universal-human beings are inherently mad, whatever the social reality. The magic of Fabelo’s art is even blacker than Goya’s, and his figures are more mythically memorable, for they are not driven mad by social forces beyond their control, but are uncontrollably mad by nature, as the wild animals they identify with suggest. Their wildness suggests that madness cannot be tamed or treated, but is incurable and inevitable.

Roberto Fabelo, El hombre, la mosca y la esperanza (The Man, The Fly and The Hope), 2009, crayon on masonite, 88” x 48.”

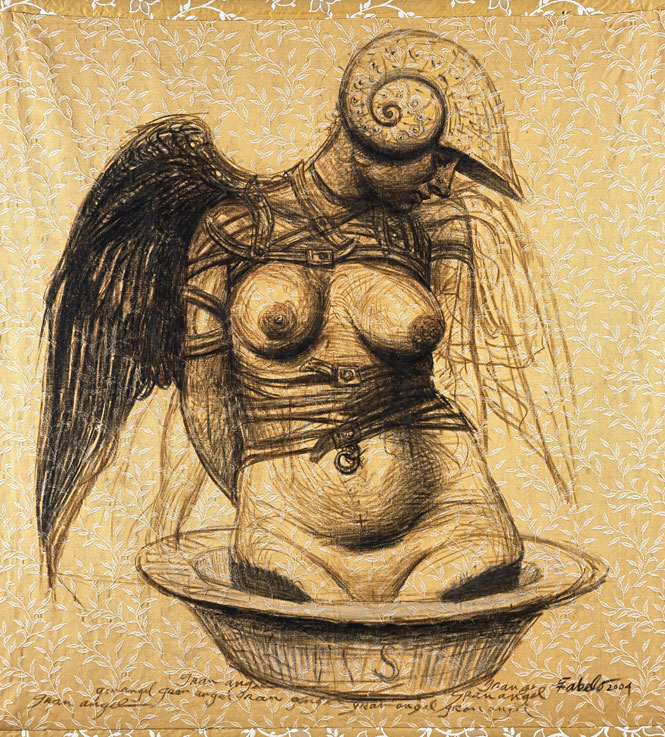

Madness is demonic, and the wild animal associated with Fabelo’s figures-as though it was a kind of alter ego–is their own “objectified demonic power,” as the psychologist Wilhelm Wundt remarked, implying that all human beings are possessed by demons. Fabelo’s figures are demons in human disguise. Women are particularly demonic for Fabelo, as his numerous images of full-bodied mermaids-all monstrously beautiful–in the ironically titled Delicatessen series (2004) makes clear. On one sheet of drawings they endlessly fuck with the devil, confirming that they are witches. (Delicatessen, that is, delicate essen, “essen” being German for “to eat.” Fabelo’s female figures are not exactly delicate food for philosophical thought, however much they may be on the mind of some of his male figures-clearly sex mad—much the way animals are on the minds of most of them. The female body is perhaps the grandest of Fabelo’s obsessions, as it has been for male artists throughout the ages.) These sadomasochistic masterpieces-the female figures passively submit to their abuse, are resigned to their horrible fate, which is to be cannibalistically eaten alive, as the bowed head and downcast eyes of the crippled Big Angel (2004) makes very clear-are consummate examples of the ironical method in Fabelo’s madness, for the fabric on which the mutilated female bodies are painted is imprinted with a lovely floral design, belying the violence done to them. Bondage and torture-not to say hatred—are rarely so explicit in Fabelo’s works, but then his mad people are inwardly tortured and hateful, for they are in bondage to the demons that inform them.

Fabelo shows their true demonic character when they become Like Flies (2010)-insects, whether grasshoppers, cockroaches, or flies, traditionally associated with the devil and death. It has been said that cockroaches will be the only survivors of a nuclear holocaust, which is why Fabelo’s Survivors (2009), a sculptural installation of gigantic cockroaches, has been read as a social statement-which undoubtedly it is-but the cockroaches are implicitly human, as Fabelo’s half-human Beetle (2008), Grasshopper Man (2009), and, less morbidly, as its title suggests, The Man, the Fly, and the Hope (2009). In the latter work the pure white milk of human kindness fills a small shallow plate far below the bloated filthy black flyman, eternally ugly however exquisitely beautiful his delicate wings. Thus the devil rides high in heaven-the fallen angel has triumphantly risen. Much the way hope was found at the bottom of Pandora’s box of ills and evils, so Fabelo finds hope deep in hell-a dialectical inversion that signals the unresolved relationship of evil, embodied in the devilish insect, and goodness, epitomized by the heavenly milk. The sacred and profane-the pure and impure, the blessed and the cursed, the angelic and the demonic—are perversely at odds, the former not standing a chance against the latter, yet holding its own, a small steady presence despite the powerful presence of the devilish flyman. The monstrous insect has pride of place, but the sacramental milk is irreplaceable: they are tied together in an emotional Gordian knot. Fabelo’s ingenious masterpiece is an eloquent re-statement of a timeless paradox.

Roberto Fabelo, Survivors, 2009, mixed media installation at National Museum of Fine Arts, 10th Havana Biennial, variable dimensions.

The naturally gross–the ugly insect—made aesthetically subtle, even surprisingly beautiful, is one of the hallmarks of Fabelo’s transformative genius. It is worth emphasizing that the indomitable cockroaches with human heads-rather than human beings with animal heads as in the Mad Portraits—signify the priority of the demonic animal over the socialized human, indicating Fabelo’s belief that we are more animal than human-crawl over the façade of Havana’s National Museum of Fine Art. This adds yet another provocative apocalyptic note to Fabelo’s morbid thinking; he seems to be suggesting that museums of art will be over-run by insect-like masses who understand nothing about art, certainly not that his art is about them-their soul portraits. They will consume the works of art like locusts, eat them as though they were pieces of cheap delicatessen. Looking at Fabelo’s Survivors, I was reminded of Nathaniel West’s Day of the Locust, a novel about Hollywood made into a Hollywood film: the same mad spectacle of the blindly destructive crowd that West describes haunts Fabelo’s work.

Art historically speaking, Fabelo is working in the grand tradition of caricature. The caricatural Art Collector (2008) makes the point clearly. Some of the earliest caricatures were made by Leonardo da Vinci. Many of Fabelo’s caricature heads have a clear affinity with the famous five caricature heads Leonardo drew. Leonardo’s grotesque head is the ancestor of Fabelo’s even more grotesque heads. “When men’s faces are drawn into resemblance of some other animals, the Italians call it, to be drawn in caricature,” the English physician Sir Thomas Browne wrote in 1716, confirming that the point of caricature is to show that people are inwardly animals however outwardly human. “Caricature” is derived from the Italian caricare, meaning to charge or load; a caricature is a “loaded portrait”-a devilish portrait, as it were, for, as Browne said, it makes the portrayed person look “monstrous” and “hideous.” Human beings are two sided or two-faced, as the English caricaturist James Gillray shows in his famous Doublures of Characters;—or-striking Resemblances in Physiognomy (1797), with their “sublime debunking,” as Gillray said, of prominent English politicians. Gillray offers us two portraits of the same politician, one showing him as he outwardly appears, the other showing his inner reality. One is a social portrait, the other a psychological portrait; Fabelo, another sublime debunker, tends to combine the two while suggesting they are in conflict. The irreconcilable opposites are absurdly reconciled in one bizarre physiognomy, making for a more complex, ruthlessly double-edged-emotionally cutting-portrait. Fabelo’s idea that the animal in us is the devil has its precedent in Gillray’s depiction of James Fox’s double as Satan with a snake around his neck and standing in the flames of hell. We Are Not Animals, Fabelo’s 2008 series ironically declares, but we are certainly grubby devils, to allude to Grub, a 2009 installation. Like Gillray, perverse comedy-satiric irony—is used to ward off impending tragedy in the act of acknowledging it, to emotionally resist apocalyptic awareness of the decline and fall of humanity while accepting its inevitability, to mockingly assert the devilish self-destructiveness of society and the imbecility of human beings as though mocking them would prevent one from becoming like them. All of Fabelo’s Mad Portraits are portraits of demented imbeciles: their personal dementia bespeaks the dementia of society as a whole. It seems Fabelo is a pessimistic fatalist who makes it clear that the world is a living hell with no hope.

Roberto Fabelo, Untitled, 2007. From “País en que los desechos son amados todavía” (Land Where the Waste is Still Loved) series, oil on canvas, 63” x 47.”

I suggest that even Fabelo’s circular Worlds (2005) and totemic Towers (2007), among other constructions of found objects, many household bric-a-brac, others bullets and bones, are caricatures: comic defenses against social tragedy, exemplified by Local Warming (2008) and Land Where the Waste is Still Loved (2007). The found objects are relics from a dead world, the tragic remains of a world gone to hell, absurdly comic in their isolated grandeur, like the mounds of domestic clothing, useless eyeglasses, and human hair in Auschwitz. Caricature is a species of satire, and satire arises when society seems decadent, more destructive than constructive, and thus tragically flawed, failing its members. Climate warming and ceaseless warfare will turn the world into a wasteland, but for Fabelo it is already an emotional wasteland inhabited by mad men and women, often acting out their devilishness in devilish sex. Again Bosch’s perverse Garden of Earthly Delight (1490-1510) and Pieter Bruegel’s Tower of Babel (1563), a futile attempt to reach heaven that ends in diabolical irony-the confusion of languages that bespeaks confused, overambitious, irreconcilable human beings—updated in contemporary terms and with modern means by Fabelo.

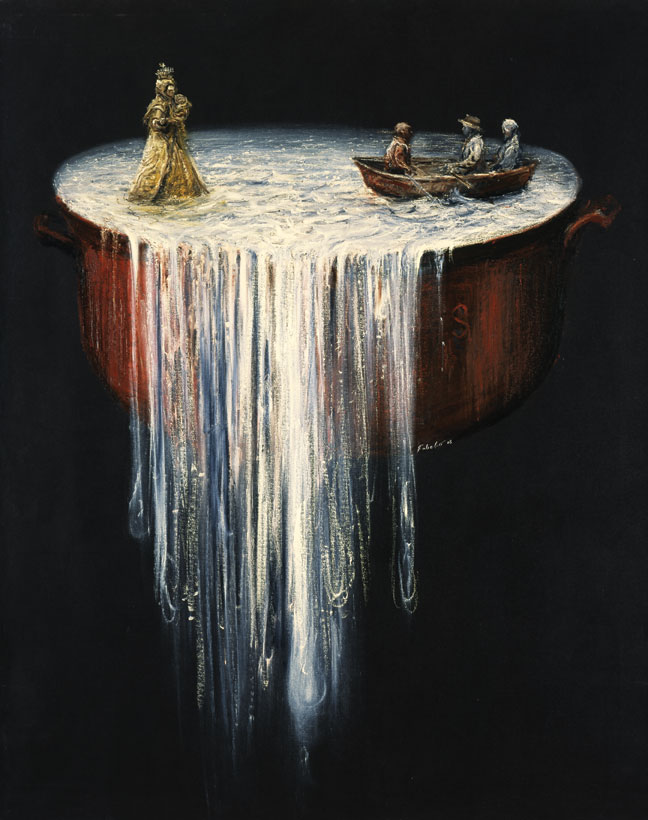

Roberto Fabelo, Untitled 02, 2008, From “Encuentro con la Virgen (Meeting with the Virgin)” series, oil on canvas, 53” x 44.”

Floating in a small boat, alone with his dog-suggesting his doggedness, the doggedness of a survivor-like the small figure precariously perched on a volcanically molten black sea in the Dreamer series (2007), Fabelo dreams of salvation, as the series Meeting with the Virgin (2008) suggests. She’s a kind of benign mirage, unexpected, considering the morbidity and madness-not to say viciousness and suffering on display—in Fabelo’s other works, but then she’s Our Lady of Charity (Our Lady of El Cobre), the Patroness of Cuba, and thus a symbol of Cuba in all sacred glory, suggesting that Fabelo deeply believes in Cuba, and has high hopes for it, however much he may question it, as he implicitly does. Fabelo has survived the apocalyptic deluge, like Noah—but he sits alone in his rowboat, his ship having sunk, while Noah’s ark survived the deluge, being unsinkable because it was built following God’s directions. Fabelo brilliantly re-figures the old symbolic myth, making it more memorable-and contemporary—by making it more personal and existential. The Virgin walks on the boiling white water like Christ, suggesting that she is God’s representative on Earth, and Fabelo now sits in his rowboat with two other survivors, suggesting all is not lost, however few earthly beings are found and chosen to survive the devastating flood. They are no longer animals, but humbled human beings, isolated in the cosmic emptiness. Is the Virgin real or is she a mirage? Do they see her or are they blind to her presence? Are they hallucinating her into existence or does she really exist independently of them? Like the milk that symbolizes hope in The Man, The Fly and the Hope, she seems out of place however clearly in the place. She seems to notice them, but they don’t seem to notice them. She turns to them, but they don’t turn to her. Sometimes they seem to be rowing toward her, sometimes they are clearly rowing away from her. Salvation is more a hopeful fantasy-perhaps a diabolic deception—than a real possibility for the apocalyptically minded Fabelo. He is clearly a major artist because he has fearlessly assimilated the diabolical contradictions in himself.

NOTES

1. Charles Baudelaire, “Some French Caricaturists,” The Mirror of Art, ed. Jonathan Mayne. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1956, 190.

2. Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, Dictionary of Symbols. London and New York: Penguin, 1996, 286-87.

Donald Kuspit is an art critic and professor of art history and philosophy at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. He is a contributing editor to Artforum, Sculpture and New Art Examiner magazines, as well as the editor of Art Criticism and a series on American art and art criticism for Cambridge University Press. Kuspit is the author of more than 20 books, including Redeeming Art: Critical Reveries (Allworth Press, 2000) and Idiosyncratic Identities: Artists at the End of the Avant-Garde (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.